This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

Money plays a central role in our economies, as does monetary policy which, along with the budget, is one of the two most important pillars of economic policy. However, monetary mechanisms are still poorly understood. They are taboo subjects in public debate, but above all they give rise to serious doctrinal errors on the part of economists on both the left and the right, which can feed into the macroeconomic models used by the most prestigious institutions, and form the basis for counterproductive, even dangerous policies.

Real progress in understanding can nevertheless be seen, particularly since the welcome clarification from economists at the Central Bank of England 1 which presents the basic mechanisms of money creation, deconstructs two misconceptions (that money is created by savings, and that its quantity is a multiple of the monetary base created by the central bank) and explains quantitative easing.

The essentials

Money is a social institution, a source of economic vitality

Money can only be conceived of as part of a socially-constructed, man-made system, based on the trust placed in it by the members of a society.

It is only useful if many people and organizations use it and trust in its benefits: its usefulness grows as it spreads.

A monetary system can only function if it is based on institutions that maintain trust. The institutions at the heart of a monetary system include :

- central bank;

- the private banking system;

- sound taxation and tax collection system;

- judicial and penal systems (for contract enforcement) ;

- the accounting system, in particular double-entry bookkeeping (for asset and liability accounts).

Traditionally, money has three functions:

- A tool for exchanging goods and services: money is the only economic object that can be instantly exchanged for any other. It is therefore first and foremost a means of payment, and cannot be refused as such when it is legal tender (or forced).

- Unit of account: money is used to express the value of goods and services in a single unit.

- Reserve of value: used to defer a purchase or investment over time. As Keynes put it, money establishes “a link between the past and the future”. This third function explains why money can be desired for its own sake, rather than to be exchanged for goods and services. This is the concept of “liquidity preference”, introduced by Keynes: the possession of money can sometimes appear preferable to its use for any other economic action.

Over the last few centuries, money has undergone a slow process of abstraction.

Initially embodied in precious metals (silver and gold), the link between physical standards and the money supply has become progressively weaker. Since the end of the Bretton Woods system and the suspension of the dollar’s convertibility to gold by U.S. President Nixon in 1971, money has no longer been based on a physical standard. It is no longer possible to convert a unit of currency into a precious metal at a predefined rate. Today, money is entirely dematerialized. 2 .

It is therefore expressed by monetary signs which can take different forms:

- Coins and banknotes immediately spring to mind: this is fiat money.

- But most money today takes the form of entries in bank accounts (whether current or savings accounts, or even financial securities): this is scriptural money.

There is also “central bank scriptural money”. However, this is only exchanged between holders of accounts with the central bank, i.e. secondary banks and the Treasury (see Essentials 2 to 4). It is not used by non-bank economic agents. It does not circulate in the economy.

The economic role of money is expressed on two levels:

- At the microeconomic level, it is used by economic agents as a means of exchange and private accumulation;

- At the macroeconomic level, monetary policy has an impact on activity and prices.

It is by looking at the distribution of the money supply, its evolution over time and the assets in which it crystallizes (consumer credit, investment credit, real estate credit, financial assets) that we can understand what a company does with its money.

According to some economists, money is neutral 3 . It is merely a “veil over trade”, a simple transmission belt. The quantity of money in circulation has no impact on economic activity other than its effect on the general price level. Too much money creation would be dangerous, as it would systematically generate inflation.

In fact, money does have an effect on activity itself, as illustrated by the correlation between GDP and money supply (see box below).

Money supply and GDP

The quantity of money in circulation is crucial to economic development.

There is a correlation between money supply and GDP 4 . This correlation is logical: since GDP represents all goods and services sold or income distributed over the course of a year, these variables are linked to money in circulation.

But the same monetary unit can be used for several exchanges or, on the contrary, be saved and not used for any purchases at all, which translates into the overall notion of the velocity of money circulation. Consequently, the total income of the various economic players is a function of the quantity of money available and of this speed of circulation, which is not constant. In addition, foreign trade can increase or decrease the money supply, depending on trends in the various balance of payments accounts of the country concerned.

That said, the correlation between money supply and GDP is confirmed by the trend: they almost always move in the same direction. When money supply increases, GDP increases, and vice versa. We can therefore deduce that an increase in the money supply is not systematically “transformed” into a rise in prices.

Money is a catalyst that makes transactions possible, and the economic development that accompanies them. This is illustrated by the story of the bounced cheque, in which a counterfeit bill was used to pay off “real” debts and stimulate economic activity.

Today, money creation stems mainly from the lending activity of secondary banks (see Essential 4 in this module): it therefore responds to a demand for financing and creates new purchasing power. This makes it possible to carry out investments and projects that would otherwise be impossible.

Under certain circumstances, money creation (private or public) can have an effect on prices. If the quantity of money in the economy increases, but is not used to generate new production, this will manifest itself as inflation, i.e. higher prices for goods and services. This can also result in higher asset prices, as in the case of old real estate: in many countries, a significant proportion of money creation in recent decades has been used to finance real estate purchases, driving up prices in this sector without any real benefit for the economy as a whole (see Essential 5 in this module).

There is also the question of the type of activity. Reducing our greenhouse gas emissions is one of the major challenges of this century (see the Economy, natural resources and pollution module). If 90% of bank credit flows to the energy sector finance fossil fuels, money creation is not helping to improve the sustainability of our society.

As well as the question of the volume of the money supply, there is also the question of its allocation. Who (which institutions) creates money? Who decides how it should be allocated? What tools does a society equip itself with to ensure that money creation meets the needs not only of the commercial sphere, but also social needs and ecological imperatives?

As we can see, all these questions are not technical: debates about money reflect issues of power. Money is fundamentally a common good, but depending on the institutional configuration governing its creation and allocation, it can be used to serve private interests.

The institutional framework of money is not immutable

As noted in the previous section, money is based on the trust of those who use it. If the acceptance of a currency by the social body does not come down to its action alone, public power 5 plays a major role, since it guarantees the legal tender status of money and “forces” its adoption by citizens and companies, notably for tax purposes. Money is thus intimately linked to the legal framework that guarantees the payment system and defines the role of the various institutions responsible for its creation and circulation.

Finally, the monetary system in force in a country (or in a monetary zone) is the fruit of a history and of specific features peculiar to that country (or zone). It is also part of an international framework in which not all currencies carry the same weight (see Essentials 10 to 12 in this module).

Central banks, keystones of the monetary system

The central bank of a country (or a zone) is an institution 6 responsible for implementing monetary policy.

The relationship between governments and central banks has evolved considerably throughout history. The 1930s and the post-World War II period were marked by the widespread adoption of the public central bank model, at the service of objectives defined by the State. Today, the model of the independent central bank dominates (even if it remains mostly publicly-owned).

As Laurence Scialom notes, “central bank practices and their sphere of action have been highly malleable over time, constantly adapting to the macroeconomic, institutional and political context”. 7 . Throughout history, central banks have pursued four main objectives:

- unify and preserve the payment system ;

- ensure financial stability. This role is twofold. On the one hand, it concerns the curative action of the lender of last resort and the market-maker of last resort, and on the other, it covers preventive actions now referred to as prudential regulation;

- maintain monetary stability and the value of the currency, either through an exchange rate target, or in the form of an inflation target;

- support the financing needs of governments in times of crisis, particularly wartime.

These objectives have not appeared simultaneously throughout history, and their relative importance differs from period to period and from country (or monetary zone) to country. Thus, while the first central banks were created in Europe in the 17th century to support the financial needs of states, this function is now widely contested in most major economies (or even prohibited in the case of the European Union), with the notable exception of China.

Secondary banks are responsible for money creation

Secondary banks are private or public companies that have the power to create the money that circulates in the economy (see Essentials 4 in this module), particularly when granting credit. They are placed under the aegis of the central bank (also known as the first-tier bank), with which they have an account.

It’s worth noting that the term bank covers a wide range of functions. Retail bank, deposit bank, commercial bank, investment bank, corporate bank… there are many different ways of naming banks, depending on their customers and the type of business they do. The ability to create money is linked to “retail banking” activities (managing means of payment, collecting deposits and granting loans).

Since the 1970s, banking deregulation has led to a blurring of the boundaries between their different business lines and a concentration of the sector, leading to the emergence of mega-banks, some of which are “universal” in the sense that they carry out both retail and non-retail activities. In this module, we refer to “secondary banks” as those with the power to create money, irrespective of their size and other areas of activity.

Most current monetary systems are heirs to the neoliberal policies of the late 1970s, inspired by monetarist theories.

From the end of the 1970s onwards, the arrival in power of political personnel committed to neo-liberal ideas led to a change in the role of central banks in most major economies, which can be summed up as follows:

- A focus on the objective of monetary stability, and in particular on controlling inflation, perceived as the major economic risk.

This is the application of monetarists’ recommendations that money only has an effect on the general price level, and that inflation is always a phenomenon linked to too much money in circulation in the economy. The main task of central banks must therefore be to maintain price stability by carefully controlling the evolution of the money supply, using interest rates as a tool.

- The generalization of the independent central bank model, seen as the institutional solution to the supposed inflationary bias of political decision-makers who, for electoral reasons, would be unable to credibly maintain inflation targets. 8

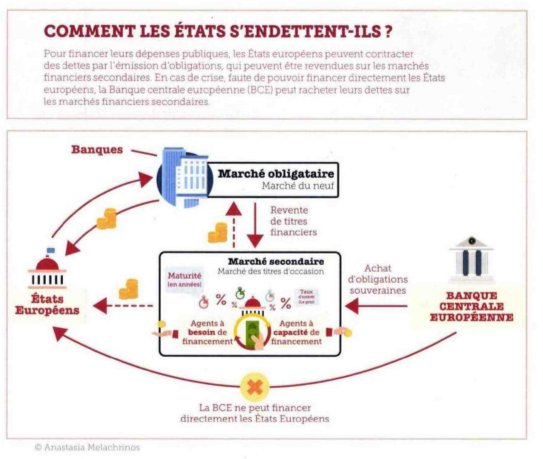

This functional separation between governments and central banks (most of which remain publicly-owned) is reflected in the prohibition (in practice, or in law in the case of the EU) of direct government financing (in other words, of direct government access to central bank loans or advances, although the central bank may purchase government debt securities on the secondary market – see the explanations on quantitative easing in this module).

These principles became the common operating framework for central banks in the developed world, even if differences remained. They have been taken to extremes in the euro zone, where they have been translated into the European Union treaties and the statutes of the European Central Bank (ECB), created at the height of the monetarist movement. However, these principles are not applied everywhere: the system in China, for example, is very different, and much more state-run and administered. 9 and most developing and emerging countries tend to have a more global mandate, more oriented towards development and more directly including questions of sustainability 10 .

Recent developments: financial stability and climate risks

The financial crisis of the late 2000s led to a number of recent developments.

- The issue of financial stability has returned to the heart of the central banks’ mandate.

This major historical function of central banks had been evacuated during the previous period and delegated to independent financial regulatory authorities. The prevailing consensus at the time was that price stability was sufficient to ensure financial stability. 11 which was largely invalidated by the financial crisis.

- Central banks have broadened their range of interventions to include so-called “unconventional” measures, such asquantitative easing, which involves central banks buying government debt securities (see our fact sheet on quantitative easing or the explanations on this subject in this module).

- Last but not least, the climate issue has also been on the agenda of central banks since then-Bank of England Governor Mark Carney’s famous “Tragedy of the Horizons” speech (2015). The financial community then began to take the measure of the systemic risks that global warming poses to financial stability (see Essential 7 in this module).

These developments have led some authors to claim that we are on the cusp of a new evolution in central bank doctrine.

Find out more

- Esther Jeffers, Dominique Plihon, “The role of central banks: what history teaches us”, Cahiers d’économie politique (2022)

- Laurence Scialom, “Les banques centrales au défi de la transition écologique. In praise of plasticity”, La Revue Economique (2022)

- Nathan Sperber, “Une finance aux ordres: comment le pouvoir chinois met le secteur financier au service de ses ambitions”, Institut Rousseau, December 2020.

- Charles Goodhart, “The Changing Role of Central Banks”, BIS Working Papers, Bank for International Settlements, December 2010.

- Eric Monnet, “Why Central Bankers Should Read Economic History”, Books & Ideas, February 2021.

Money supply continues to grow

First of all, it’s important to understand the difference between the monetary base and the money supply.

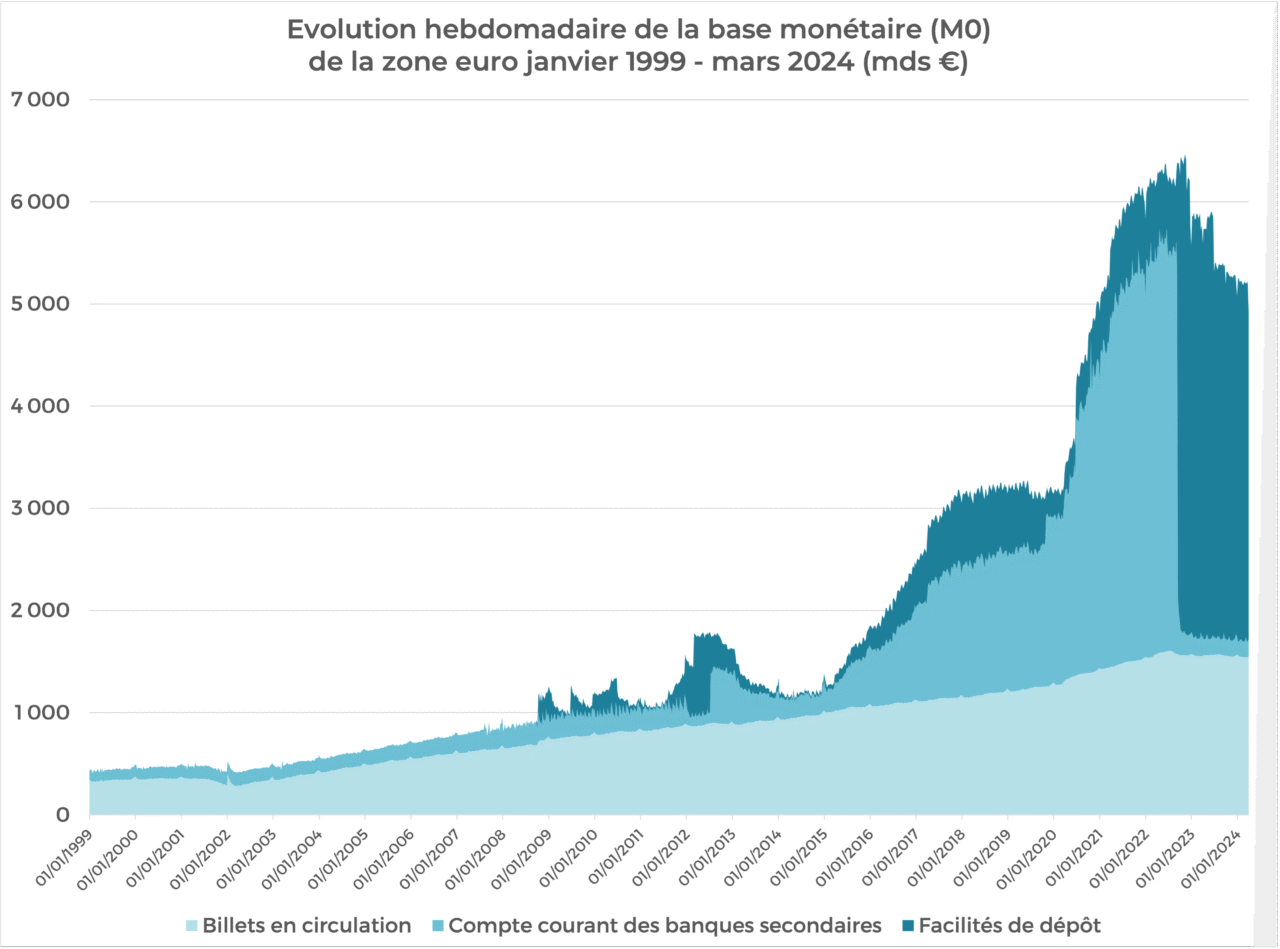

The monetary base (noted M0) is made up of the money created by the central bank, known as the “monetary base”.

It includes :

- scriptural central bank money, i.e. the reserves held by secondary banks on their accounts with the central bank (plus deposit facilities). 12 ). This money is created by the central bank to meet the liquidity needs of secondary banks (see why secondary banks need it in the relevant section ). It does not circulate in the economy: it is only used for exchanges between banks, or between each bank and the central bank;

- banknotes in circulation in the economy: the central bank has a monopoly on issuing banknotes, which it supplies to secondary banks so that they can meet their customers’ requests for withdrawals.

Source Data set “Eurosystem consolidated statement” on the European Central Bank website (and more specifically the series: banknotes L010000; credit institutions’ current account L020100 and Deposit Facility L020200).

As can be seen from the graph, the monetary base has grown steadily since 1999, with accelerating growth following crises (the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the eurozone crisis in the 2010s and the COVID pandemic crisis in 2020).

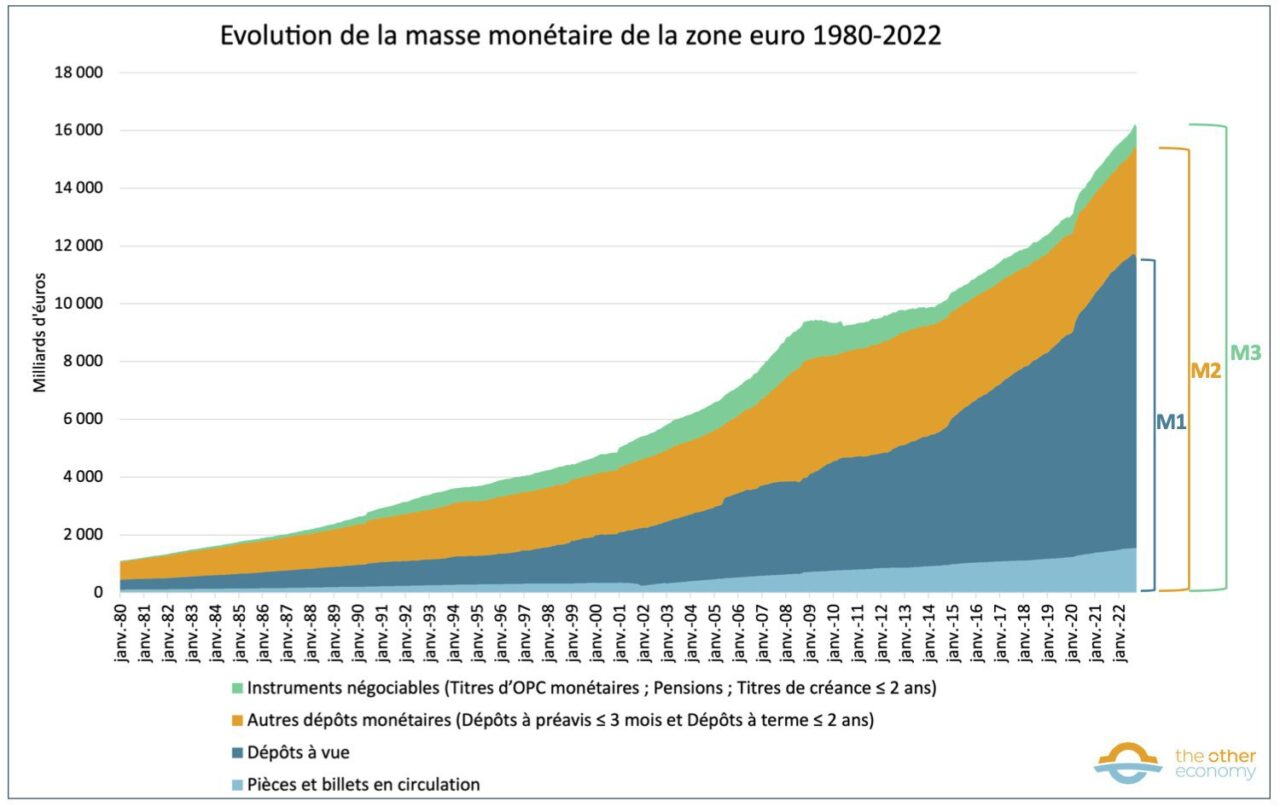

Money supply refers to the total quantity of money in circulation in an economy.

As we saw in Essentials 1 of this module, money is made up of different instruments: banknotes and coins, as well as accounting entries in the current accounts of economic players. Strictly speaking, money is a means of making a payment or extinguishing a debt. Legal tender cannot be refused by a creditor.

But economic agents also have other bank accounts and savings accounts or passbooks that are available more or less easily and quickly (more or less liquid). For example, money placed in savings accounts cannot be used directly to pay a bill: at the very least, you need to make a prior transfer to your current account, or even ask your bank for authorization (and possibly pay an exit fee) before you can use it.

This is why money is sometimes seen as a continuum of more or less liquid instruments. This vision is linked to the monetarist viewpoint, according to which it is essential to know (and possibly limit) the quantity of means of payment in circulation. A passbook account or a SICAV security that can be transferred free of charge and with little or no delay are seen as quasi-money. It’s also true that investment behavior varies according to the level of interest rates. It is therefore clear that there is a continuum between current accounts and highly liquid investment instruments.

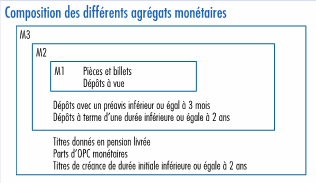

Following this logic, central banks divide the money supply into aggregates that fit together like Russian dolls, moving from the most liquid instruments to the least liquid. 13 .

The European Central Bank distinguishes and monitors three interlocking monetary aggregates: M1, M2 and M3.

- M1 is the narrowest aggregate: it refers to money in the strict sense of the term, i.e. money that is immediately available to make payments (i.e. coins and banknotes in circulation and sums available on current accounts).

- M3 is the largest aggregate.

As can be seen from the following graph, whatever the aggregates considered, the eurozone’s money supply has been rising steadily for decades. This is also true of the other major monetary zones: the United States, Japan, China, etc.

Eurozone money supply (1980-2022) in billions of euros

Source Monetary developments in the euro area (accessed December 2022). To access the long series, simply click on the figures in the PDF document.

There has therefore been continuous money creation, mainly by second-tier banks (see Essential 4 in this module).

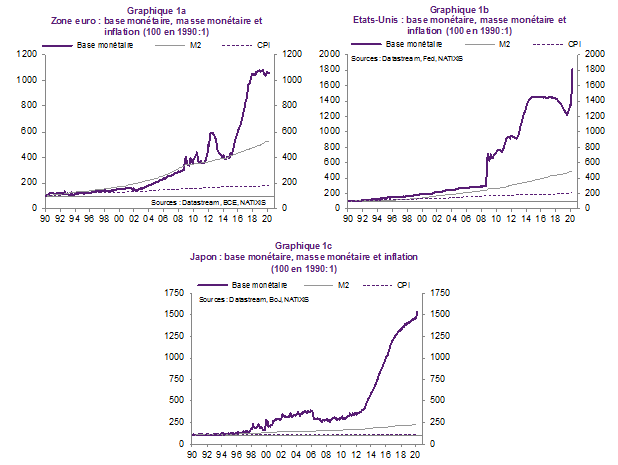

Finally, a comparison between the evolution of the monetary base and the money supply reveals that the relationship between the two is not constant. This refutes the theory of the money multiplier, according to which the money created is a multiple of the monetary base.

Money circulating in the economy is created by secondary banks

As explained in an educational document from the Banque de France, the entries made in bank accounts during credit transactions are the source of money creation, and more specifically, the creation of book money.

Credits make deposits

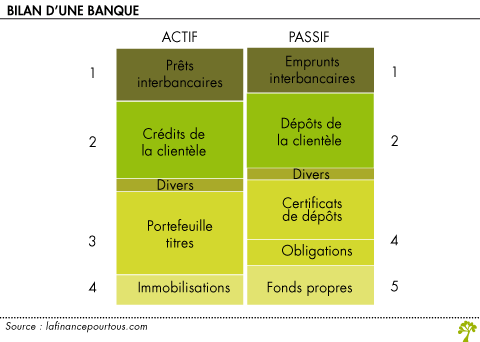

All companies, including banks, have an accounting and financial balance sheet, a snapshot at a given moment of what they own (assets) and what they owe (liabilities).

Source La finance pour tous

When a secondary bank grants a loan of €100k to an economic agent (an individual or a company, for example), it records this €100k simultaneously as an asset (a loan the bank has on its customer) and as a liability, via a deposit in the customer’s current account. In other words, “loans make deposits”.

The scriptural money thus created can then be converted into fiduciary money (banknotes) simply by withdrawing it at the bank counter.

This money is destroyed when the customer repays the loan. For the money supply to increase, the volume of loans granted must exceed the volume of loans repaid. Ultimately, it is the secondary banks that “create” money by granting loans to economic agents.

What about banknotes?

As noted in Essential 3, the central bank has a monopoly on issuing banknotes (fiat money). However, this “manufacture” of banknotes is not the origin of money creation: it is its consequence.

The quantity of banknotes in circulation in an economy depends on agents’ preference for holding their money in this form rather than in their bank accounts. In the eurozone, banknotes represented around 13% of the M1 money supply at the end of 2020. 14 . This means that if M1 increases by €100 (due to new loans granted by banks), the demand for banknotes by economic agents is likely to increase by around €13. The secondary banks will therefore have to obtain €13 of banknotes from the central bank to meet potential withdrawal requests from economic agents.

Money is therefore first created in scriptural form and then converted into banknotes via withdrawals by economic agents. So it’s not a central bank decision that motivates the release of new banknotes into circulation, but the demand for credit and the willingness of agents to have their money in this form. If no one asked for banknotes any more, the volume of the money supply would not change: only the form of money would (which would then be entirely in scriptural form). It’s the expansion of the money supply as a whole that implies the expansion of the quantity of banknotes, not the other way round.

There are several other cases of money creation

When a currency is deposited at a bank counter, the bank creates euros to buy that currency, and symmetrically, when a private individual buys a currency, the euros used for that purchase are destroyed.

More generally, as Jean Bayard writes, any increase in bank assets contributes to money creation. 15 . Let’s quote him more fully:

“The bank monetizes its expenses (losses) and demonetizes its income (profits) […]. So, for example, it creates money when it pays its staff salaries by crediting their accounts, and it destroys money when it debits its customers’ accounts for interest, agios and other charges owed to it. In short, the bank monetizes every time it buys and pays, and demonetizes every time it sells and collects […].” For example, a bank writes checks “on itself” when it pays an expense. When it makes payroll 16 of its employees, it directly credits the personnel accounts by debiting its expense account.

This very special power to create money is granted only to banking institutions in the strict sense of the term. 17 which can both collect deposits and make loans (among other operations). Their chart of accounts benefits from an exemption from the rules governing customer money, enshrined in national and European regulations. This allows them to hold funds as liabilities, known as “bank deposits”, instead of holding funds in a separate bank account, as is the case for all other economic players, including non-banking financial institutions. The latter cannot create money: they can only lend it out if they have borrowed it or if they have collected savings to match. Moreover, they have a bank account with a “real bank”. This is also the case for all shadow banking .

The most important thing to understand is that commercial banks don’t just lend out the deposits they collect (see misconception 3 in this module), or transfer money they’ve received from the central bank: they “produce” the scriptural money that makes up the bulk of the money supply.

Distinguishing mutual credit from money-creating credit

There are two types of credit.

Mutual credit is where Peter lends Paul a sum of money. It is also where a non-banking financial institution lends money to an economic agent, corresponding to savings already built up. In so doing, it does not create purchasing power. It simply transfers it in the form of money.

Credit that creates money, and therefore purchasing power, is when a bank lends money created ex nihilo. This credit is temporary, and you’d think that repaying it (i.e., destroying money) would restore the initial situation. But this is not the case. In fact, at constant or increasing speeds of money circulation, if there are more new loans than repayments of old loans, purchasing power is created. This is generally the case when economic conditions are good. The opposite is true in times of depression: there may be more loan repayments than new loans, with a slowdown in the velocity of money circulation and, consequently, a contraction in purchasing power.

Find out more

Some explanations from central banks:

The power to create money must be overseen by public regulation

As we saw in Essential 1 of this module, the creation of money is crucial to economic activity. Banking is therefore not an economic activity like any other: it is at the service of other activities, and must contribute to the needs of society as a whole. This power thus belongs to the general interest, to the public good, and not to private interests. Indeed, if misused, money creation can have harmful effects on society and the economy. What’s more, it gives banks an inordinate amount of power. For obvious democratic reasons, it cannot be entrusted unchecked to the private sector. As we shall see in section 6 of this module, there are ways of controlling private money creation, but they are too limited.

The volume and allocation of money creation have a major impact on the economy and society

We have already seen that the volume of money creation is a determining factor for economic activity. Created to provide credit, and therefore linked to a need for financing, money creation can have an effect on the volume of activity, increased by this credit. Conversely, too little money creation (or too much money destruction) can lead to recession, or even economic crisis, a major risk that needs to be contained. In short, the “endogenous” money created via credit has a procyclical effect (amplifying the economic cycle).

However, the importance of money creation is not limited to its volume, but also to its allocation. Loans are determined by demand from economic agents and by the profitability prospects that banks derive from them. This in no way guarantees that they will be directed towards the most socially useful activities, especially if these activities have a high social or ecological added value but a low return. 18 . On the other hand, if banks grant loans that do not contribute to increasing the volume of production, and if the speed of circulation of money does not slow down, then prices may rise.

This is what has happened over the past few decades. On a global scale, credit rose from around 73% of GDP in the early 1980s to almost 130% before the 2007-2008 crisis. 19 . However, this disconnect between credit and production has not led to higher prices for goods and services (i.e.,inflation). Indeed, the majority of money creation was captured by the real estate sector and financial markets, which themselves experienced recurring bubbles, factors in regular financial crises with devastating economic and social impacts. We use the example of real estate below to decipher these mechanisms.

The example of real estate

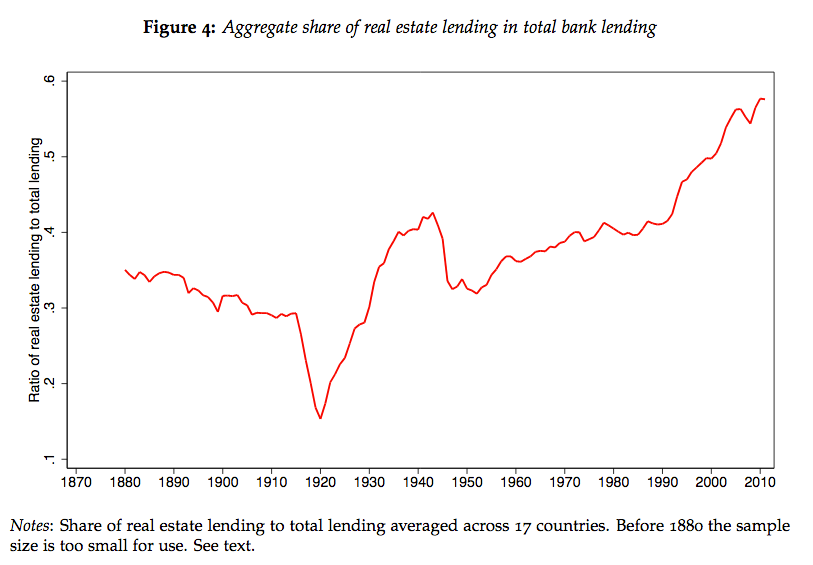

From the end of the 1970s onwards, as a result of banking deregulation, banks concentrated their lending activities on real estate lending, in particular because of its attractive characteristics: credit risk analysis is less complicated than in other sectors (e.g. loans to SMEs). The loan is generally secured by a mortgage on the property acquired, which reassures the lender, as it provides a valuable counterparty in the event of non-repayment.

A study published in 2014 20 shows that in the early 2010s, real estate accounted for nearly 60% of outstanding bank loans in 17 advanced economies.

Source Oscar Jorda, Moritz Schularick and Alan M. Taylor, The Great Mortgaging, NBER working Paper Serie, 2014.

This development is problematic for several reasons:

On the one hand, real estate lending is at least partly at the expense of other activities. For example, at the end of 2019 in France, real estate loans accounted for around 51% of loans to non-financial customers resident in France; loans for business investment only 17%. 21 and much less, obviously, for investment in the ecological transition.

On the other hand, mortgages essentially finance 22 the purchase of existing homes. Since the growth in the volume of mortgages has been higher than that of production (the construction of new homes), it has pushed up housing prices. This rise in property values, which is reflected in housing rents, creates obvious social injustices. In particular, it makes it impossible for low-income households to gain access to the best schools. It has equally obvious ecological consequences, driving urban sprawl, since it’s far from attractive urban centers that low-income households can find affordable housing. Finally, it leads to the formation of real estate bubbles. These bubbles form according to a momentum logic, i.e. a self-sustaining cycle of rising prices and credit volumes.

This mechanism is therefore based on an increase in indebtedness, which does not appear to be a problem in the upward phase of the cycle: borrowers appear to be solvent, since the value of assets acquired through indebtedness is rising (so they could always resell them to make repayments). Problems arise precisely when some borrowers can no longer meet repayments: they start to sell, causing prices to fall and eventually bursting the bubble. Over-indebtedness then becomes obvious, as the price of the underlying goods (or assets) falls.

There is a strong risk of entering a deflationary spiral in which debt reduction efforts contribute to an increase in the proportion of debt to income or wealth. This is what is known as debt deflation, a phenomenon identified by Irving Fisher as early as the 1930s. 23 .

This is what happened in Japan with the bursting of the real estate credit bubble in the 1990s, which plunged the country into deflation from which it still hasn’t completely emerged. And, of course, it was the bursting of the sub-prime mortgage bubble that brought the country to the brink of deflation. 24 in the USA in 2007, which triggered the 2008 financial crisis and plunged the country, and then the world, into recession.

When speculative bubbles burst, the consequences affect a large number of economic players, exacerbating poverty and inequality.

The risk of financial collapse

The fact that a bank can lend money created ex nihilo means that it can face a liquidity crisis on two main occasions. Firstly, it may experience a “bank run ” when its customers lose confidence, leading to a banking panic. Customers seek to withdraw banknotes (legal tender), but the bank never has enough to meet all these demands. The last spectacular episode was that of the Northern Rock bank in 2007.

On the other hand, a bank may find itself unable to meet its commitments to one of its peers, or no longer inspire confidence in it, which can also lead to bankruptcy. A bank failure can lead to other bank failures, because of the links between banks, and cause difficulties for companies or households who are creditors and may lose their assets (current accounts and deposited savings). This is why a public deposit guarantee system has been set up in France. 25 .

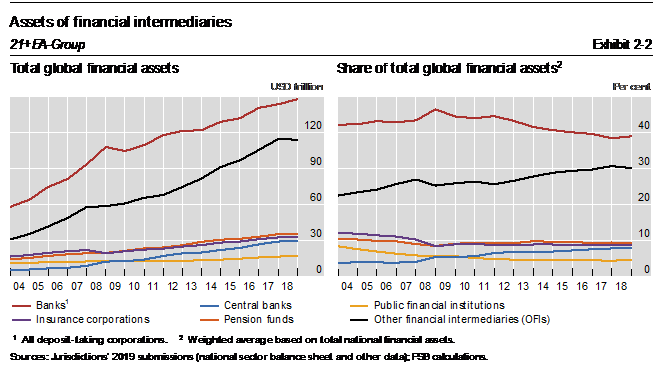

These risks, strictly linked to money creation, have increased since the financial liberalization of the late 1970s. The international financial system is characterized by the existence of increasingly large institutions, and by growing interconnection between the various players. Within this system, banks play a decisive role. According to the Financial Stability Board, total global financial assets amounted to almost $379,000 billion at the end of 2018 (equivalent to 4.5 years of GDP).

Source FSB, Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation, 2019

Monetary policy and its limits

As we saw in Essential 2 of this module, central banks’ mandates and tools have evolved over time, and differ from one country or monetary zone to another. Here, we focus on the tools used today by central banks in advanced economies (with the notable exception of China). 26 ), and in particular the European Central Bank 27 . However, it is important to bear in mind that central banks (and governments when central banks were more closely dependent on them) have had other tools at their disposal to control money creation and allocation (e.g., credit control and steering, advances and loans to the Treasury, monetization of public spending).

What monetary policy tools are available to central banks?

The central bank is the “bank of banks”: just as every economic agent has an account with a banking institution, every secondary bank has an account with the central bank. This account is replenished with money created by the central bank (known as the “monetary base”). 28 ), which is used exclusively for exchanges between banks. 29 . It does not circulate in the economy. The monetary policy pursued by central banks mainly consists of supplying this monetary base to secondary banks and setting its price.

Why do banks need central bank money?

Firstly, banks need to obtain banknotes to meet their customers’ demands for withdrawals (see Essentials 4 in this module). Secondly, some central banks 30 require banks to hold reserves of central bank money in their accounts with the central bank. These reserve requirements are calculated as a percentage of the deposits they collect. This is an initial tool for limiting bank money creation, but it is little used in the euro zone. 31 where the reserve requirement is very low (1% since 2012).

Last but not least, banks need central bank money to settle payments with other banks arising from transactions between their customers. If there were only one bank, the millions of daily transactions 32 carried out between its customers would manifest themselves in movements between accounts held by that single bank: there would be no “leakage” of money to other banks. This case is, of course, fictitious, as transactions between economic agents imply that, once bank clearing has taken place 33 some banks find themselves in debit with others. They then need central bank money to settle what they owe each other.

When a bank needs central bank money, it can :

- or borrow from another bank on the interbank market

- or borrow directly from the central bank.

Central bank loans, known as refinancing operations, are very short-term loans (24 hours, one week or a few months). 34 whose interest rates, known as key rates 35 are set by the central bank.

Before the crisis of 2007-2008, this was the main monetary policy tool. In fact, it influences all other interest rates: those on the interbank market, those on the money market, and so on. 36 bond markets and credit markets. It thus has an impact on money creation by influencing the cost of bank loans to the economy (businesses, individuals, etc.). A rise or fall in the key rate slows or speeds up loan applications, and therefore money creation. It also has an impact on economic activity, as the cost of credit influences the ability of economic agents to consume or invest through borrowing.

In return for borrowing from the central bank, banks are also required to temporarily sell (or “repo”) financial assets that serve as collateral for the central bank’s loan (rather like a mortgage on a house). These assets, known as “collateral”, must meet minimum (financial) quality criteria, such as a satisfactory rating from the rating agencies.

The central bank can also provide monetary base by purchasing debt securities held by banks. These two tools (loans and purchases of securities) were used differently by the various major central banks: the ECB favored the loan tool, while the Fed and the Bank of Japan relied more on the purchase of securities.

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 and so-called “unconventional” tools

In response to the 2008 financial crisis, central banks made extensive use of conventional tools. In the eurozone, for example, the minimum reserve ratio has been 1% since 2012. The ECB has also steadily lowered its key rate: from 4.25% in July 2008 to zero from March 2016. It only became positive again in July 2022, following the rise in inflation (in December 2024 it stood at 2.9%, having peaked at 4.5% in September 2023. Source: BdF).

As these tools proved insufficient to prevent the collapse of the financial system, central banks had to implement so-called “unconventional” monetary policies, which consisted of providing banks with more liquidity via longer-term loans than previously and massive purchases of debt securities (so-called quantitative easing ) 37 . These tools, initially mobilized to counter the risk of financial collapse linked in particular to the paralysis of the interbank market (see box), are still widely used today.

The role of “lender of last resort

For the interbank market to function, banks must agree to lend to each other, which implies that they have confidence in each other’s solidity. When mistrust sets in, there’s a risk that the financial system will collapse, as banks will no longer lend to each other. Without the central bank, a debtor bank would no longer find the liquidity to pay what it owes, and would go bankrupt. As the players in the financial system are interconnected, this first failure, if it involves a large bank (known as systemic ), would cascade down to other banks. The central bank is said to play the role of “lender of last resort”.

The main unconventional policy is quantitative easing (QE). These are operations in which the central bank supplies monetary base to secondary banks by buying back large quantities of mainly public (but also private) debt securities. For the most part, central bank purchases therefore take place on the secondary market. 38 .

Source Marc Pourroy, La dette publique aux mains de la BCE, Revue Projet, 2021.

Quantitative easing has several consequences:

- At the level of secondary banks, QE increases their reserves in central bank money, which should increase their capacity to grant loans and thus boost economic activity: banks are less afraid to lend since they have easy access to central bank liquidity, and economic agents are more inclined to borrow due to very low interest rates. In addition, it reduces secondary banks’ holdings of sovereign debt, thereby reducing their exposure to the risk of sovereign default.

- State level 39 QE reduces the cost of debt. Indeed, by announcing that they are going to massively repurchase government debt securities, central banks guarantee (implicitly or explicitly) that there is a buyer of last resort for government debt. Banks are then assured that they will be able to easily sell sovereign debt back to the central bank, making it easier for them to buy securities issued on the primary market. This reduces the risk of sovereign default, puts downward pressure on interest rates on government debt and limits speculative ardor. What’s more, since most central banks are publicly-owned, the interest paid by governments accrues at least in part to them in the form of dividends. QE therefore helps to improve governments’ ability to finance their budget deficits.

To find out more about quantitative easing, see our fact sheet on the subject .

The limits of monetary policy

An indirect role in the volume of money circulating in the economy

Looking back over the monetary history of the last 10 years, it’s impossible to deny that the accommodating policies of central banks have had a real impact on the economy. They have prevented the collapse of the financial system and the devastating consequences this would have had on economic activity. Secondly, they facilitated the financing of public debt, enabling governments to continue mobilizing their budgets to cope with the economic crisis following the 2008 financial crisis, and even more so with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the impact of these policies remains limited, as can be seen from the comparison between the evolution of the monetary base and the money supply (see the relevant section and the graphs below). The increased liquidity injected into the banking system by central banks has not translated into a corresponding increase in credit.

This is due to the endogenous nature of money creation: economic agents are the originators, through their demand for credit (and not a decision by the central bank). Banks grant loans if the operation is profitable and the customer is solvent. Monetary policy, via the key interest rate and the provision of liquidity, can make this operation more or less profitable for banks, and more or less costly for borrowers, but it cannot force borrowers to borrow. The demand for credit from households, businesses and public authorities depends on many factors, of which the availability of cheap credit is only one. Their financial situation (income and level of debt) and their confidence in the future (company order books, state of the job market, etc.) play a major role.

When the economy is in a state of quasi-deflation and the outlook is poor, private players (households and companies) take a wait-and-see attitude. Even if interest rates are low, they tend to seek to reduce their debt or put money aside. They also anticipate future price declines, and wait before making purchases or investments. This is the “liquidity trap” phenomenon.

No role in money supply allocation

While central banks play an indirect role in the volume of money supply, they play none in its allocation. Their action is neutral 40 . It is the secondary banks that determine the recipients of money creation: they constitute a permanent and inescapable filter between the actions of central banks and economic players.

The key interest rate, a major tool of monetary policy prior to the 2007-2008 crisis, can only make credit more or less accessible to businesses and households. However, it has no influence on the allocation of credit: its rise or fall has an equal impact on all sectors of the economy and all regions. A rise will increase the cost of credit for real estate, renewable energies and any other economic activity. Conversely, a fall will reduce the cost of money for productive investment, but also for speculation and polluting activities. Similarly, in monetary zones such as the eurozone, a rise in the key interest rate can be useful for certain overheating national economies, while others, in a more depressed situation, would on the contrary benefit from an easing of credit conditions.

Unconventional policies also have no influence on credit allocation. First of all, it should be remembered that these policies provide central bank money, but not money that can be used by non-financial agents. As a result, they have largely led to the liquidity thus created being held in reserve in bank accounts at the central bank. This is one of the explanations for the growing disconnect between the monetary base and the money supply (see Related Essentials).

Secondly, whether central banks buy assets or take them as collateral, they are generally pre-existing assets acquired on the secondary market. In so doing, they influence the price of securities, but only indirectly on their supply, and very indirectly on the financing of the original issuers. Indeed, buying a debt security or a share at the time of issue does not have the same economic consequences as buying it on the secondary market: only the first option contributes directly to investment by financing the issuer, while the second contributes above all to improving the liquidity of its assets and therefore lowering bond yields. It also feeds speculation and the formation of bubbles, as greater demand pushes up asset prices. Last but not least, going through the secondary market feeds all kinds of financial intermediaries, starting with banks, via the commissions they receive.

Poverty in monetary policy is not inevitable

This limited role of monetary policy in the volume and allocation of money creation is not inevitable. It is the result of the dominant doctrine in this area, inherited from the 1970s and 80s: monetary policy, conducted by a central bank independent of governments, must focus on price stability. It must be neutral, not favoring one sector over another.

This doctrine is currently evolving, in particular as a result of the emergence of the issue of financial risks resulting from global warming (see Essential 7 of this module). Numerous research studies and think tanks are highlighting the fact that the tools already mobilized by central banks could be “greened”, put at the service of the ecological transition. They also point to the need to rehabilitate other tools, in particular the monetization of public debt.

Risk-based approach slows down central bankers’ action on climate change

In September 2015, in a now historic speech delivered at Lloyd’s headquarters 41 Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, asserted that global warming presented risks with potentially systemic financial consequences. He introduced the concept of the ” tragedy of horizons “: the short-term horizons of financial players do not allow them to identify the long-term risks they run as a result of global warming.

It also provides a typology of these risks (more details in the finance module):

- physical risks (impact of climatic disasters on companies, production chains, trade);

- transition risks (impact of economic changes linked to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions on carbon-intensive businesses);

- and liability risks (legal action).

Central banks, whose role in maintaining financial stability was reaffirmed in the wake of the 2007-2008 crisis, have taken up this subject. Thus, in December 2017, the NGFS was created. 42 a network of central banks and supervisors for the greening of finance, whose aim is to ” contribute to strengthening the global response required to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement and enhance the role of the financial system in managing risks and mobilizing capital for green and low-carbon investments “. Moreover, central bankers are increasingly taking a public stance on the importance of taking global warming into account. 43 .

The stated aim is therefore twofold: to help financial players take better account of climate risks, and to mobilize them to provide more funding for transition projects. This is what we call double materiality: the financial system is threatened by global warming, and conversely, financial activities contribute to aggravating the phenomenon.

Supervisors and central bankers focus on risks

For the time being, however, the work of central banks has focused on the first dimension: estimating the risks that the climate poses to financial institutions and, more generally, to the financial system as a whole (systemic risk).

This approach is based on the logic developed by Mark Carney in his speech on the “ tragedy of the horizons “: as financial players are currently unable to take climate-related financial risks into account, we need to make them visible so that finance can take them into account and bring the rest of the economy along with it.

It is therefore a sequential approach:

- As a first step, we need to develop research, methodologies and regulations to 1/ improve the transparency, quality and quantity of information on climate risks borne by non-financial companies, and 2/ precisely quantify the exposure of financial players to these risks.

- In a second phase, market players can adjust their strategy and, if they still fail to do so, the authorities can adopt new prudential and regulatory measures.

This approach is in line with traditional risk management by financial players, and is based on two problematic assumptions:

- Once the new information was available, the markets, having become efficient in this respect, would be able to correctly evaluate(price) green assets and carbon assets, and thus adjust their investment strategy. This hypothesis, which is based on the theory of market efficiency, is however invalidated both in fact (multiplication of financial crises) and in theory.

- The financial risks induced by global warming would be identifiable and measurable, which is far from being the case, as we shall see.

The financial risks of global warming cannot be measured

The traditional approach to risk management in finance is based on probabilities established on the basis of historical data extrapolated into the future. For example, the future default risk of SMEs is calculated on the basis of historical default data for this type of company.

This approach is inoperative when it comes to financial climate risk. Historical data cannot provide a solid basis: climate change is not linear, and there are tipping points and thresholds which, once crossed, could cause global warming to spiral out of control. 44 . Financial climate risks have a longer time frame than traditional financial risks; their materialization has irreversible consequences, and their costs are potentially infinite.

As Hugues Chenet and Wojteck Kalinowski write in their article note from the Veblen InstituteClimate change, and more generally all environmental risks, place us “. (…) Radical uncertainty characterizes situations where there is no calculable probability of a particular future occurrence. The future is then unknown. In other words, if radical uncertainty prevails, financial risk is not calculable. This undermines the whole logic of taking financial risk into account. “.

Focus on risk-based approach leads to wait-and-see attitude of supervisors and central bankers

As Laurence Scialom notes, the traditional approach to risk management is proving not only unsuitable, but counter-productive.

“If the radically new nature of an event, with a potentially massive impact on asset prices, cannot be associated with a probability in the absence of historical data, financial risk can no longer be quantified. Worse still, the continued use of these methods necessarily leads to their serious underestimation, and is therefore an impediment to the calibration of monetary and macroprudential policies likely to better control them.”

This is what we see when we look at the reports and recommendations of the NGFS and, more generally, of central banks. 45 . While they testify to a real awareness of the climate crisis and the need for resolute action, the recommendations appear very limited. They essentially call for more research to quantify climate risk in terms of financial losses, while acknowledging the complexity of the financial impacts of climate change and the potentially insurmountable technical and theoretical obstacles they entail.

The NGFS is also developing scenario-building exercises to explore possible futures, which seem better suited to the radical uncertainty that characterizes the issue of global warming. However, these are conducted from a quantitative perspective, with a view to carrying out climate stress tests, a new tool for supervising financial institutions. Inspired by the financial stress tests introduced in the wake of the 2007-2008 crisis, these consist in quantifying the financial impact (for an institution, a portfolio or the financial system as a whole) of the materialization of climate risks according to a given scenario.

This risk-based approach is clearly inadequate: above all, it leads financial regulators and supervisors to stand still, waiting for “more research”.

Are green assets less risky than polluting assets?

A positive answer to this question, which features prominently in the work of the NGFS, is a prerequisite for any prudential or monetary policy that favors green assets or disfavors polluting assets (fossil fuel companies, for example). However, given the current state of the economy, there is no reason why a “green” company should be less at risk of default than a polluting one. In fact, the opposite is sometimes true. 46 . Green” assets will only be less risky when the economy is truly on a transition trajectory – a trajectory which, for the moment, is just one hypothesis among many.

While the dynamic may well be reversed as a result of political decisions or a major move by a significant player, there is no reason why a risk differential should be observed at present until this shift is perceived by the majority of players. Here again, the risk-based approach does little to help. On the contrary, it would be desirable not to justify stricter regulation because carbon assets are measured as being riskier today, but rather to strengthen regulation to penalize them because they are riskier for the climate. Then they will become financially riskier.

What are the alternatives?

If knowledge of the quantification of financial risks is inherently inadequate, should we wait for hypothetical perfection before taking action? What we do know about the material impacts of climate change, as summarized in the IPCC reports (see Economy, Natural Resources and Pollution module), is more than sufficient. We know with certainty that inaction in the short term will lead to an increase in climate-related disasters; that the costs to the economic system, and hence to the financial system, will be massive, given the positive feedback loops that characterize the crossing of planetary limits.

So how can we prevent financial risks that are completely beyond the reach of traditional risk management tools? Alternative approaches are emerging from research and think tanks, even if some publications and speeches by central bankers have not yet been published. 47 show the beginnings of a shift in doctrine.

- Recognizing the “double materiality” of global warming

It’s not just a question of calculating the financial risks resulting from climate change, but also of taking into account the impact of finance and financed economic activities on the climate. This means recognizing environmental criteria as criteria in their own right, in addition to financial criteria, in the policies of regulators and supervisors.

- Taking precautions

Just because climate-related financial risks are very difficult to estimate, doesn’t mean they don’t exist. Scientific knowledge of the climate proves beyond doubt that global warming will have a massive impact on living conditions on the planet and on accessible resources. It will also have a massive impact on the economy, and therefore on the financial system. This should provide a sufficient basis for action, mobilizing the existing tools of central banks and financial supervisors.

Hugues Chenet and Wojteck Kalinowski recommend, for example, “. content ourselves in the short term with the most obvious actions (…) resort to a priori satisfactory measures, basic rules (or rules of thumb) drawn from accumulated knowledge and experience of crisis management. An example of a rule of thumb would be to start by tackling the financing of the most harmful activities, where a broad consensus exists in at least some jurisdictions (coal-fired power stations, oil sands exploitation, etc.), using the arsenal of tools available to central banks, including asset buybacks, collateral eligibility, credit control, etc. . “. They also stress the need for adaptive, flexible and regularly reviewed policies.

The response to COVID-19 offers an interesting parallel: the emergency measures adopted by central bankers did not require risk calculations and modeling exercises as complex as those that dominate today’s response to global warming. In the case of climate change (and environmental crises in general), we need to act upstream, as a precautionary measure, because once the risks have materialized, it will be far too late. It has to be said, however, that these emergency measures have concerned a public health problem that is much more limited in its consequences than global warming. We might therefore hope that it will provoke an even more vigorous reaction!

Find out more

- For a “Whatever it takes” climate, Veblen Institute (2020)

- Finance, climate-change and radical uncertainty: Towards a precautionary approach to financial policy, Ecological Economics (2021)

- Developing a precautionary approach to financial policy – from climate to biodiversity, INSPIRE research Network (2022)

- Les banques centrales au défi de la transition écologique : éloge de la plasticité, Energy and Prosperity Chair (2020)

- The role of monetary policy in the ecological transition: an overview of different greening options, Institut Veblen (2020)

Private money creation is procyclical, a source of debt and financial instability

As we saw in Essentiel 4, money creation today is carried out in return for the indebtedness of a public or private economic player.

As a result, it mechanically contributes to the rise in indebtedness. 48 and its creation costs the borrower interest. Today, however, indebtedness is a major macroeconomic problem, leading to cautiousness and a lack of investment, as many economic agents give priority to reducing their indebtedness.

Debt money has a second disadvantage. Its issuance is a function of economic conditions, amplifying rather than regulating cycles. When the economy is depressed, economic agents are unwilling or unable to take on debt, and bankers find it difficult to lend. As a result, money is not created and may run out. Conversely, when the economy overheats, excess money can be issued, creating inflationary pressures. The authorities are then forced to take action on interest rates, which in turn can trigger recessionary processes.

Finally, this mechanism is not unrelated to the increase in financial crises. Overheating” may not be “calmed” by the authorities, resulting in a financial bubble that may burst (see the relevant Essential). Put another way, excessive indebtedness is a source of instability, leading to the risk of recession or financial crisis.

Conversely, a free currency, created and injected without debt in exchange 49 has, symmetrically, three advantages:

- its creation does not generate debt;

- it’s free;

- it can be issued to stimulate activity when the economy is in recession.

Contrary to popular belief, monetary financing of the State has been possible, and has indeed made it possible to inject money without incurring debt in return. This was the case when money was made up of coins or banknotes issued by the State.

Giving the State back the benefit of money creation would enable it to reduce its indebtedness.

The link between money creation and public debt is obvious in theory: if the State benefits from money creation, it does not incur debt to match. And it is the only actor with the legitimacy to do so. This is known as “monetizing public debt”.

In fact, it has been proposed that money creation should be exclusively of public origin. This is the notion of 100% money introduced by the economist Irving Fisher. 50 supported by Maurice Allais (for whom bankers are counterfeiters) 51 ). The idea is to demand that the central bank cover (or reserve) 100% of the scriptural money created by secondary banks. It is advocated in particular by the NGO Positive Money. Two IMF economists analyzed and supported it in 2012 52 . In Switzerland, the“Full Money” initiative, launched in 2016, aimed to give the Swiss National Bank a monopoly on money creation. It was put to a “vote” (popular initiative referendum) in June 2018, but was rejected by 76% of the votes cast.

In Europe, the idea of monetizing public debt comes up against the European Union treaties and the statutes of the European Central Bank, which formally prohibit direct advances from the Bank to governments and public administrations. This prohibition is legitimized by the doctrine that the State must submit to market discipline (see preconceived notion 5 in this module): by being obliged to borrow from the market, it must justify its sound management. Recourse to “printing money” would allow it to take advantage of anti-economic facilities. This prohibition is relaxed on the secondary market: the ECB can buy sovereign bonds on this market, the essential condition being that these bonds have first been subscribed on the primary market (see explanations on quantitative easing in this module).

The stakes are high. Indeed, the snowball effect means that as soon as the interest rate is higher than the growth rate, public debt increases mechanically, unless the State generates sufficient primary surpluses.

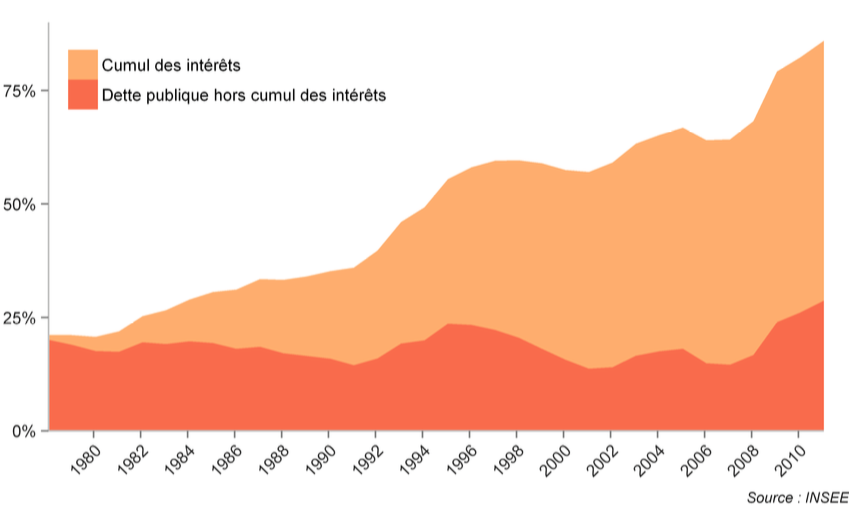

In a 2012 article 53 Rossi Abi-Rafeh, Gaël Giraud and Florent Mc Isaac analyzed the evolution of French public debt from 1980 to 2011: from around 25% of GDP in 1978 to 86% in 2011.

The authors break down the formation of this debt into what is due to the interest burden and what is due to the primary deficit (i.e. before interest payments). They conclude that “if the French State had taken on debt at zero interest, our gross public debt today would have been 28.5% of GDP in 2011 (instead of 86%), all other things being equal”. Put another way, if the State’s financing needs had been met by money creation without debt and interest, then its debt ratio would have been stable overall.

Source Rossi Abi-Rafeh, Gaël Giraud, Florent McIsaac, La dette publique française justifie l’austérité budgétaire, 2012

The first negative consequence of financing the State through debt is that interest charges weigh heavily on its accounts. The higher the interest rates, the higher the interest burden, and the greater the effort required to limit it. One might therefore think that the amount of public debt is not in itself a problem (independently of the formal or legal constraints linked in Europe to the European treaties), if the interest rates paid on sovereign debt are zero (or even negative) as they are today. Put another way, since the sustainability of public debt depends first and foremost on interest rates, monetization would be pointless in times of low interest rates.

This analysis is not very convincing. On the one hand, it is not necessarily economically desirable for interest rates (which are not only used to finance public debt, but are passed on throughout the economy) to be zero – it depends on the context. What’s more, their level can vary. There’s no guarantee that they won’t rise again. If they do, interest costs will rise again. It’s a sword of Damocles. Last but not least, the vast majority of the public perceive public debt (as a proportion of GDP) as a major economic constraint. Even if this is a belief rather than a truth, it must be taken into account when choosing options.

Floating exchange rates are a source of economic and social difficulties

The end of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971 54 led to the abandonment of fixed exchange rates between the “major” currencies. For Milton Friedman, floating exchange rates were necessary because 1/ money is a commodity like any other and 2/ markets are efficient; therefore, the price of a currency should be set freely on a market.

A country that indulges in fiscal laxity financed by money creation will have a “weak” currency, so that economic players will prefer other currencies. Conversely, the “virtuous” will have a strong currency. This is how, in a framework of floating exchange rates, market mechanisms will spontaneously punish bad monetary policies.

The end of the Bretton-Woods agreements

The system set up after the 1944 Bretton Woods conference was a fixed exchange rate system with a gold exchange standard based on the dollar alone. An ounce of gold was worth $35. Other currencies were defined either directly in relation to the dollar, or by the price of gold in dollars. Exchange rates were fixed but adjustable: a country could devalue or revalue its currency, provided an adjustment plan was implemented and the other countries agreed. The IMF was responsible for supervising this mechanism.

This arrangement gave the dollar a special place. As US current account deficits were financed by dollars, the United States chose not to worry about them. This attitude is known as benign neglect. During the 1960s, U.S. military spending and the space race led the U.S. government to multiply spending and create a huge international liquidity in dollars. This license first attracted the remarks of General de Gaulle, who, in a famous conference, called for a return to the gold standard and began demanding payment in gold, instead of dollars.

In 1971, it was Germany that put an end to the Bretton Woods agreements: annoyed at having to buy dollars at a fixed rate above the natural market rate – which amounted to paying US inflation for them – the BUBA, the German central bank, sensitized to inflation by the hyperinflation of the early 1920s, stopped accepting them. President Nixon then decided to abolish the dollar’s gold convertibility.

This irenic vision of flexible exchange rates clashes with reality, as Robert Mundell has shown in an indictment of most of the arguments in favor of flexible exchange rates 55 . In particular, he asserts:

- that exchange rates have never been stable, but rather dramatically volatile;

- that interest rates have not converged either;

- that it is speculation that has taken hold, with numerous erratic attacks against currencies, an analysis confirmed by other economists 56 ;

- that the shocks were not mitigated but exacerbated by floating exchange rates;

- that floating exchange rates lead to endogenous financial instability.

Most currencies are non-convertible

This section draws heavily on the report “ La finance aux citoyens – Mettre la finance au service de l’intérêt général ” ( Finance for citizens – Putting finance at the service of the general interest ), of which we have summarized or reproduced several passages from chapter 5. 57 .

The currencies of the “advanced countries” are convertible currencies (sometimes called “hard” currencies). 58 as a misnomer). This means that they can be exchanged between each other without restriction or authorization: with euros, you can buy dollars, yen or pounds sterling. You can also buy Russian rubles or Indian rupees with euros; but this is not true in the other direction. The rouble and the rupee are “non-convertible” currencies in the international monetary system, controlled by the IMF. An individual or a French company based in India must request authorization from the Indian central bank to convert the rupees they hold into euros. The Indian central bank will refuse this authorization if no euros are available at the time of the request. This situation often occurs in many emerging countries 59 .

Currency non-convertibility restricts access to international financial resources

Global finance only concerns transactions in convertible currencies. There are currently 18 60 . The world’s 180 or so other currencies are subject to exchange restrictions, and their countries have only limited access to the resources of global finance: they can only borrow in convertible currencies if they can repay, i.e. if they export to countries holding this type of currency. In these countries, finance is essentially local: convertible currencies, used by the major global multinational banks, play only a relative role in their economies.

There are, of course, varying degrees of access to convertible currencies for emerging and developing countries. Those that export heavily to advanced countries have substantial hard currency reserves. Even if their currencies are technically inconvertible, in practice loans and borrowings in convertible currencies are easy and plentiful. This is the case in Chile, for example, but above all in China, the world’s largest holder of US dollars. China has two currencies: a domestic currency, the yuan, and a foreign currency, the renminbi.

But for most emerging and developing countries, restricted access to convertible currencies makes it difficult for non-resident companies to invest, and for local companies to expand, due to the additional costs associated with justified or perceived mistrust on the part of partners (suppliers, banks, etc.).

Countries without access to convertible currencies are vulnerable to currency speculation

The exchange rate of a country’s currency has a direct impact on the lives of its citizens. When the currency depreciates against other currencies, the price of imported products rises, which can cause major economic and social problems, for example if the country imports energy, foodstuffs or materials and machinery essential to its industrial activity. At the same time, the price of exported products falls, making them easier to sell in other countries, thus boosting exports.

A currency can depreciate if it is created in abundance in the country, but also if it is “attacked” by speculative movements from outside the country.

Currency speculation can also affect convertible currencies, even if it is made more difficult by the fact that advanced countries have free access to the market for other convertible currencies: to counter an attack, they generally just need to borrow 61 . For emerging and developing countries, this borrowing is much more difficult for the reasons already mentioned, and they are therefore much more vulnerable to currency speculation than advanced countries.

Currency depreciations in emerging and developing countries have been frequent and significant since the introduction of floating exchange rates in 1973. The most severely affected countries between 1990 and 2010 were Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina and Russia. From the late 1990s onwards, these countries experienced banking and currency crises that caused them to lose up to 15% of their GDP, in the case of Indonesia. 62 an overall effect far greater than that of the 1929 crisis in the United States and Europe. The Mexican peso, for example, fell by 50% between 1994 and 1995; the Thai baht, the Malaysian riggit, the Indonesian rupee and the South Korean won fell by 50-70% in 1997. The Russian rouble lost 50% of its value in 1998. 63 . Under these conditions, it is difficult to believe that the floating exchange rate regime and the free movement of capital have been beneficial for these countries.

Pegging to a convertible currency gives access to international capital, but can impose severe constraints on the population.

Many countries have either adopted a hard currency as their currency or pegged their currency to a hard currency. 64 (by choice or obligation) to a hard currency (in practice, the dollar, yen, Swiss franc, euro and ruble). 65 . For example, Ecuador, Panama and El Salvador have chosen the dollar as their currency. Some twenty countries have pegged their currencies to the dollar 66 . China, for example, pegged its yuan to the dollar from 2000 to 2010. West African countries have pegged the CFA franc 67 to the euro (it was pegged to the franc when it was created), as have Eastern European countries.

This stowage can be at a higher or lower rate. In the case of China, it was done at a low rate 68 to encourage the country’s development through exports (the yuan was undervalued against the dollar at the time) 69 ). The pegged currency then follows the rate of the reference currency. If necessary, it can become overvalued. The level of the initial exchange rate is therefore crucial for the country or zone concerned.

A peg gives the country access to international financing, as investors do not fear the risk of convertibility and are less concerned about the risk of exchange rate losses (as the exchange rate of the non-pegged currency is generally more volatile). It supports the competitiveness of exported goods if the exchange rate used is low. What’s more, when they repatriate the fruits of their exports in their local currency, companies benefiting from this advantageous exchange rate can considerably increase their profits. Pegging helps to protect one’s own economy from exchange rate fluctuations.

But it also has negative consequences for the economy of the country adopting this policy, since the State gives up all or part of its monetary sovereignty and therefore its ability to adjust fluctuations in the economy through its monetary and exchange rate policy: it can no longer resort to public money creation to regulate its indebtedness; it loses the ability to devalue or revalue its currency; it must also combat “tendencies” towards inflation that would be higher than that of the zone or country of the reference currency, which may lead it to compress wages. It is also an economic loss for the central bank to collect the seigniorage rights inherent in money creation. Finally, pegging must be defended: the government or central bank must constantly buy or sell foreign currencies to maintain parity with the pegged currency, which requires large amounts of foreign exchange reserves.

A strong currency is no guarantee of social well-being for the country concerned.

The creation of the euro was preceded by a long plea for the franc to be pegged to the mark, a strong currency. The citizens of France, Spain and Italy were asked to make major sacrifices, as the franc’s parity was maintained by raising interest rates (which made it more attractive and exerted upward pressure on its value) and implementing a policy of austerity from 1983 onwards (after several devaluations following attacks on the franc at the start of Mitterrand’s first term in office).

In a floating exchange rate regime, a “strong” currency is one which is “in demand” (by third-country investors or residents) because it is considered to be unable to lose value (relative to other currencies). A “weak” currency is one which investors fear will lose value, and which they shy away from to avoid exchange losses on eventual resale. At the time of the creation of the euro zone, the weak currencies (Spanish peseta, Italian lira, Greek drachma and, relative to the mark, the franc) had undergone several devaluations.

In a floating exchange rate regime, the parity of a currency depends on supply and demand in the foreign exchange market, and on the actions of the central bank, which can intervene in this market (coordinating with other central banks where necessary). 70 ) to support its currency.

Technically, economists calculate whether a currency is undervalued (“weak”) or overvalued (“strong”) in relation to another by calculating the purchasing power parity (PPP) of the two currencies: the PPP exchange rate between the domestic currency and the foreign currency is such that one unit of domestic currency can be used to obtain the same quantity of goods and services, at home and abroad, once conversion has been made. If the PPP exchange rate is lower than the effective exchange rate, the currency is overvalued, and vice versa.

The calculations made by economists are complex, sometimes contradictory and often debatable. To understand the concept, let’s take the example provided by The Economist with its ” Big Mac Index “, which tracks the price of Mac Donald’s sandwiches around the globe. At the end of January 2007, a Big Mac cost an average of 2.94 euros in the euro zone, compared with 3.22 dollars in the United States, giving a purchasing power parity of 1.10 dollars to the euro. At $1.36, the euro would be overvalued by 24% (compared to $1.10), according to the “Big Mac Index”. Conversely, the Chinese yuan is undervalued, according to this index, by 56% against the dollar 71 .

The advantages of a convertible currency are clear (see the Essentials in this module). But what about a hard currency? The supposed advantages are as follows:

- imports are less expensive, so a strong currency limits price rises. All other things being equal, it helps to reduce the cost of credit, since interest rates are all the lower as inflation is also lower, which is good for consumers and businesses;

- the State has easy access to international financing, as the currency is in demand. If it is heavily indebted internationally, its government has no interest in defending a strategy of weakening the currency, as the resulting rise in interest rates would increase the cost of public debt;

- a country with a strong currency is more likely to attract foreign investment (and possibly head offices), thus generating activity, dynamism and jobs. The reason is always the same: these investors, because of the “strength of the currency”, do not fear exchange rate losses.

Yet it is clear that the “Asian dragons”, and especially China, have developed at great speed thanks to an undervalued currency.

The disadvantages of a strong currency are symmetrical to the advantages:

- a strong currency makes exported products less competitive 72 in countries with weaker currencies ;