This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

While tax concealment is undoubtedly as old as taxation itself 1 it has taken on a new dimension since the 1980s. The rise of globalization, the opening up of capital markets, the growing role of multinationals in the world economy and the development of digital technology have led to the development of tax havens and international tax evasion. Wealthy individuals have thus been able to avoid paying taxes on part of their wealth and income in their own countries, while multinationals have been able to move a growing proportion of their profits to low-tax or even no-tax jurisdictions.

The loss of public revenue resulting from these practices is considerable. At the start of the 2020s, almost 10% of corporate tax revenues – i.e. around €200 billion – are lost to governments every year. 2 As for wealthy individuals, Gabriel Zucman, one of the leading specialists on the subject, put forward the figure of 155 billion in lost tax revenue per year in 2017. 3

This fact sheet explains what tax evasion is, its main manifestations and recent developments in international regulation. By revealing the extent of the phenomenon and its deleterious consequences, the 2007-2008 crisis marked the beginning of a new international focus on tax issues, under the impetus of the G20 and the OECD.

In this fact sheet, we focus on international tax evasion by multinationals and wealthy individuals, the challenges on which international policies have focused over the past decade. We do not, therefore, deal with the full range of tax optimization, evasion and fraud practices (such as VAT fraud, for example). 4 ).

What is tax evasion and what are its consequences?

Tax optimization, tax evasion and tax fraud: definitions

According to the Cour des Comptes 5 tax evasion refers to “all operations designed to reduce the amount of tax normally payable by the taxpayer, the regularity of which is uncertain”. It lies in the grey area between tax optimization and tax evasion (see box). In this fact sheet, we are mainly concerned with international tax evasion, which consists of playing with tax loopholes by placing some or all of one’s assets and/or income in low-tax countries, without expatriating there.

International tax evasion by wealthy individuals often takes the form of fraud, since it involves hiding assets or income abroad without declaring them to the tax authorities. For multinationals, tax evasion generally takes the form of aggressive optimization. They exploit “legal loopholes in tax systems and asymmetries between national rules to avoid paying their fair share of tax”. 6 Tax evasion generally falls within the limits set by the law, but is often contrary “to the spirit of the law, relying on a very extensive interpretation of what is ‘legal’ to minimize a company’s overall tax contribution.”

Tax optimization, tax evasion and tax fraud: a continuum

There is a continuum of tax avoidance, from legal optimization to fraud and evasion, which lies at the interface between the two.

Tax optimization is the use of legal means to reduce tax liability. It is normally based on real economic activity. It may be legitimate, or even encouraged by the government, as in the case of “tax niches“, tax reductions introduced by the state to encourage certain activities. 7 While the merits of some of these niches can be contested, it is difficult to reproach a taxpayer for choosing options that cost him the least. Tax optimization can also be described as “aggressive”, flirting with abuse of rights (flouting the spirit of the law) or even bordering on legality.

Tax fraud is the practice of evading taxes by illegal means. Examples include various forms of VAT fraud tax evasion, failure to declare income (such as rental income or dividend payments), or moving capital to foreign jurisdictions without notifying the tax authorities.

Tax havens at the heart of international tax evasion

Of course, tax evasion is not just a matter for companies and businessmen, but also for dictators or oligarchs and their families, criminals, professional sportsmen and women, media and film stars, and so on. It generally involves opaque and complex arrangements, with the creation of shell companies such as trusts, or foundations in tax havens.

They are the heart of the system. Without them, tax evasion and avoidance would not have developed on the scale it has today. Although all the ingredients were in place in the first half of the 20th century (see box), it was the opening up of the capital markets in the 1980s that gave them their decisive importance.

The three pillars of tax havens

The first tax havens appeared at the beginning of the 20th century, at a time when the main mechanisms that made them so successful were being invented.

Pillar 1: attract companies with low or non-existent tax rates.

At the end of the 19th century in the United States, business lawyers encouraged the states of New Jersey and Delaware to offer tax caps to any company moving there, in exchange for registration fees.

Pillar 2: the fictitious residence.

In 1929, judges in the UK accepted that a company with a registered office abroad could be a tax resident in that country, and therefore not liable to UK tax. Multinationals realized that setting up a fictitious company in a low-tax country was enough to avoid paying tax in their home country.

Pillar 3: banking secrecy.

The Swiss Banking Act of 1924 placed banking secrecy under the protection of criminal law: an employee of a Swiss bank who provides information on the identity of his customers, whether domestic or foreign, is now committing a criminal offence.

Tax havens at the heart of the markets Alternatives Economiques (28/10/2021). On the history of tax havens, see also Tax havens Christian Chavagneux, Ronen P. Palan, La Découverte, 2017.

What is a tax haven?

There is no official, universally accepted definition of what constitutes a tax haven. The following is the definition adopted by the OECD in 1998 in the report Harmful Tax Competition: A Global Problem .

This definition uses four criteria to qualify a country or territory as a tax haven:

- a zero or insignificant tax rate ;

- legislative or administrative provisions preventing the exchange of tax information with other countries;

- a lack of transparency regarding the country’s tax practices;

- the “absence of an obligation to carry out a substantial activity” for a company (i.e. being very tolerant of shell companies).

In addition to these criteria relating to the legal and regulatory system, tax havens are characterized by the existence of a large ecosystem of financial institutions (including the largest banks, insurance companies, etc.). 9 ), consulting and auditing firms (in particular the “big four 10 ), and specialized law firms. These services are referred to as offshore because they are offered to non-resident individuals, who can access them from a third country.

As Pascal de Saint-Amans, then Director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration, points out, the development of tax havens and offshore finance relies on the complicity of international finance and the laissez-faire attitude of the international community.

“We mustn’t forget that it was the investment banks who, thanks to globalization, offered tax products in the 1990s, who created these excesses. And the states didn’t coordinate and created an avenue for tax advice.”

Finally, as researcher Vincent Piolet explains, tax havens provide their “users” with services that are not limited to tax evasion or fraud. Opacity and secrecy are also important objectives.

“The individual will seek to minimize tax on his income and assets, and will desire anonymity and low tax rates. Criminals wishing to launder their money will turn to countries with which judicial cooperation is weak and highly opaque. Large corporations who see tax as a mere variable in an equation to be maximized will practice aggressive tax optimization, allocating their subsidiaries to low-tax host countries. Banks and insurers will seek out weak legislation to circumvent prudential rules and create increasingly risky but potentially high-yield financial instruments without any controls.”11

Which countries are tax havens?

While certain institutions and countries have drawn up lists of tax havens (or, more precisely, of “non-cooperative states and territories”), in reality this exercise is proving to be rather artificial, if not counterproductive. Geopolitical and diplomatic stakes mean that states that are too important economically and/or politically are not included on such lists.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the OECD “black list” drawn up at the request of the London G20 included just 4 territories (before disappearing a few days later).12

The example of the European Union is also illuminating. Since 2017, the EU has updated an annual list of list of non-cooperative states and territories (ETNC) on the basis of three main types of criteria (tax transparency, tax fairness and implementation of measures “aimed at combating tax base erosion and profit shifting” 13 ).

In 2024, this list includes 12 countries, none of them members of the European Union, even though some of them could be included because of their aggressive tax practices (some of which have been revealed by tax scandals). Indeed, the European Parliament notes ironically that “the European list only concerns third countries” and that “the Union’s influence in the fight against tax evasion and harmful tax practices worldwide depends on the example it sets ‘at home’.” 14

This point highlights the asymmetries within European economic governance. European economic governance in terms of denouncing member state behavior deemed problematic. Thus, while the Stability and Growth Pact puts in place complex procedures to monitor, denounce, put back on the “right track”, and even punish member states deemed to be overspending. Nothing similar is in place for European tax havens, which deprive their neighbors of some of their tax revenues.

The Tax Justice Network’s work to identify tax havens

Far less subject to geopolitical and diplomatic constraints, work from civil society is far more interesting. Created in 2003, the Tax Justice Network a coalition of researchers and activists working to combat financial crime, has developed two indicators.

The Financial Opacity Index (FSI) measures the degree of opacity of a jurisdiction. It is calculated by combining an “opacity score” (which aggregates some twenty twenty or so indicators relating to ownership registration, transparency of legal entities, integrity of tax and financial regulation, and international cooperation) to the country’s overall weight (measured by the value of financial services provided to residents of other countries).

The Corporate Tax Haven Index (CHTI) measures the degree to which a jurisdiction facilitates tax evasion and avoidance by multinational companies. It is calculated by combining the “tax haven score” (which aggregates some twenty or so indicators on the various rules, laws and mechanisms that multinationals can use to evade corporate tax), and the weight of the jurisdiction (measured by the volume of financial activity carried out in the country by multinational companies).

These two indicators are interesting because they not only rank countries according to the aggressiveness or opacity of their tax systems, but also include their weight in offshore financial activity. This makes it easier to identify the risks posed by these jurisdictions in terms of financial opacity, fraud and tax evasion. In addition, they offer the possibility of studying the various dimensions making up the indicators on a country-by-country basis.

The deleterious impact on society of tax havens and international tax evasion

International tax evasion has many negative consequences.

First of all, it’s obvious that the opacity of tax havens is conducive to money laundering and the financial circuits of criminal activities such as human trafficking, drug trafficking and terrorism.

Beyond its most visible and media-friendly aspects, tax evasion increases inequality. 15 It is the wealthiest individuals who benefit most from the opportunities offered by offshore finance, as they have more assets and income to invest there, and can afford to use tax advisors and other law firms specializing in tax avoidance.

They benefit directly by avoiding taxes, and/or indirectly through the higher profits of the companies whose shares they own.

Tax havens also lead to an underestimation of the level and growth of global inequality, as the wealth invested in them disappears off the statistical radar.

As noted in the introduction, public revenue losses due to tax evasion by wealthy individuals and multinationals were estimated at almost 350 billion euros worldwide in the early 2020s.

In reality, they are more important, as this type of practice has contributed to tax competition between countries. In order to attract or maintain economic activity, they have progressively reduced corporate taxation 16 (see point 3 on corporate tax avoidance and our Module on inequality).

Faced with shrinking public resources, governments are forced either to raise taxes on the population as a whole, or to cut back on public spending, and therefore on public services that have a redistributive effect, thus contributing once again to the rise in inequalities.

While all countries are affected (with the exception, of course, of tax havens), developing countries suffer disproportionately from international tax evasion, due to the importance of corporate taxes (and in particular those paid by multinationals) in their resources, and the enormous needs they have to develop their health and education systems.

In ecological terms, this weakening of governments’ financial capacities makes it particularly difficult to finance the massive investments investments required for the ecological transition .

Growing inequality, accentuated by tax evasion, also undermines the ability to implement ecological policies, particularly when they take the form of environmental taxes or incentives to reduce consumption. There is too great a gap between unbridled consumption and the fraudulent practices of the ultra-rich, revealed by the repeated tax scandals of the last decade. In the module oninequalities, we explainthat they are a brake on the ecological transition.

In economic terms, tax evasion is a source of unfair competition between multinationals and domestic companies, which cannot afford to pay the tax consultants needed for aggressive tax optimization practices, nor to set up the complex legal arrangements needed to localize profits elsewhere than in their country of activity. This undermines the fairness and integrity of tax systems, which de facto favor multinationals to the detriment of other companies.

Tax havens also play an important role in financial instability. As journalist Christian Chavagneux explains, “the majority of toxic products in the American banking system were registered in the Cayman Islands; the British bank Northern Rock went bankrupt after it was discovered that it was dependent on excessive debt concealed in Jersey; the risks taken by Lehman Brothers were concealed in a web of 8,000 subsidiaries in Luxembourg, Switzerland and Bermuda. So havens are not just tax havens, they also attract financial players because they enable them to take risks in a concealed way.” 17

Finally, the scale of international tax evasion revealed by repeated scandals (see section 1.4) is one of the factors undermining democratic systems. As the European Tax Observatory notes, “In modern economies where governments generate a large proportion of tax revenues by taxing consumption and wages, tax evasion on the profits and capital of the most powerful economic players risks undermining the social acceptability of taxation.” 18 When governments announce, in the name of budgetary rigor, that they want to cut public spending or raise taxes, this can only fuel feelings of injustice and social protest.

States taking back control

The 2007-2008 crisis revealed not only the role of tax havens in financial instability, but also the scale of international tax evasion and the extent of its negative consequences. At the G20 summit in London, the declaration issued by the heads of state and government marked the beginning of the international community’s slow return to the issue of taxation.

“We agree to take action against non-cooperative jurisdictions, including tax havens. We are ready to apply sanctions to protect our public finances and financial systems. The era of banking secrecy is over. “

This is all the more legitimate given that the 2010 decade has been punctuated by the almost annual revelation of tax and financial scandals by the media.

Investigation after investigation, the large-scale system of tax evasion and opacification of financial flows is brought to light. Relying on the complicity of major players in international finance, this system is characterized by highly complex legal and financial arrangements, based on a tangle of shell companies located in tax havens. The latter include territories dependent on large states, as shown by the example of the US state of Delaware, cited in the Panama Papers as harbouring financial arrangements of this type.

One tax scandal a year!

Revealed by the investigations of consortia of journalists, in particular the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (CIJI), tax scandals are often based onleaks of documents transmitted by whistle-blowers. Here are some of the most important.

2014 – LuxLeaks

Leakage of internal documents from the four largest audit firms (PwC, Ernst&Young, Deloitte and KPMG) relating to “tax rulings”, agreements concluded between 340 multinationals (including Apple, Verizon, Heinz, Ikea and Pepsi) and the Luxembourg tax authorities to allow them to derogate from the ordinary tax system.

2015 – SwissLeaks

This leak reveals how HSBC Suisse helped shelter millions in accounts linked to arms dealers, dictators and tax evaders.

2016 – Panama papers

The leak of 11.5 million secret documents from 40 years of archives of Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca reveals the schemes used by many individuals to conceal their assets and income from their country’s tax authorities. The cases also involve more than 210,000 companies in 21 jurisdictions.

2017 – Paradise papers

An ICIJ investigation uncovers the tax avoidance mechanisms used by multinationals and the world’s wealthiest individuals, through law firms and companies specializing in offshore finance and located in tax havens.

2018 – CumEx Files

These cases shed light on arrangements based on the so-called dividend arbitrage method, involving the sale of shares to avoid the withholding tax on dividends. These practices are estimated to have cost France 33 billion in tax revenues over 20 years, according to data published in October 2021 .

2019 – Mauritius leaks

Multinationals use the tax haven of Mauritius to avoid paying taxes to countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East and the USA.

2021 – Pandora papers

A leak of 12 million confidential documents reveals the true owners of more than 29,000 offshore companies from over 200 countries, including Russia, the UK, Argentina and China.

Read more : Before the “Paradise Papers“, what ten years of financial investigations have changed, Le Monde (06/11/2017)

In parallel with the essential investigative work carried out by consortia of journalists, the OECD, under the impetus of the G20, has launched several major initiatives to tackle international tax evasion.

These dynamics, which have resulted in a new form of international cooperation long considered utopian, cover two main areas:

- Put an end to banking secrecy through the automatic and multilateral exchange of banking information, applied by more than 120 countries by 2024. See section 2.3

- Adopt international standards to combat tax evasion by multinationals. To this end, the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on the BEPS project has adopted an action plan comprising 15 main types of measures 19 . In particular, by 2021 almost 140 countries and jurisdictions have adopted an international agreement on a global minimum corporate tax. See section 3.3

Since 2023, the UN has also taken up the subject.

On December 22, the United Nations General Assembly adopts the resolution for the Promotion of Inclusive and Effective International Cooperation in Tax Matters establishing an Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Committee to draft the terms of reference for a United Nations Framework Convention on International Cooperation in Tax Matters. At the August 2024 session of this committee, the broad outlines of the future convention, with particular emphasis on combating tax evasion and avoidance by multinationals and wealthy individuals, were approved, despite the abstention or even the vote against of some fifty countries (mainly developed countries). 20

Fraud and tax evasion by wealthy individuals

Households’ offshore financial wealth includes financial assets 21 held by individuals outside their country of residence. Such holdings are not illegal per se.

Tax evasion consists of an individual’s failure to declare his or her assets (when the country applies a wealth tax) and/or the income generated by these offshore assets (such as interest, dividends and capital gains) to the tax authorities in his or her country of residence.

As we shall see, this type of fraud has been considerably reduced thanks to the automatic exchange of tax information that has developed over the last 10 years. However, it has not completely disappeared, and other tax evasion practices have developed.

Offshore financial wealth remains very high despite recent tax transparency policies

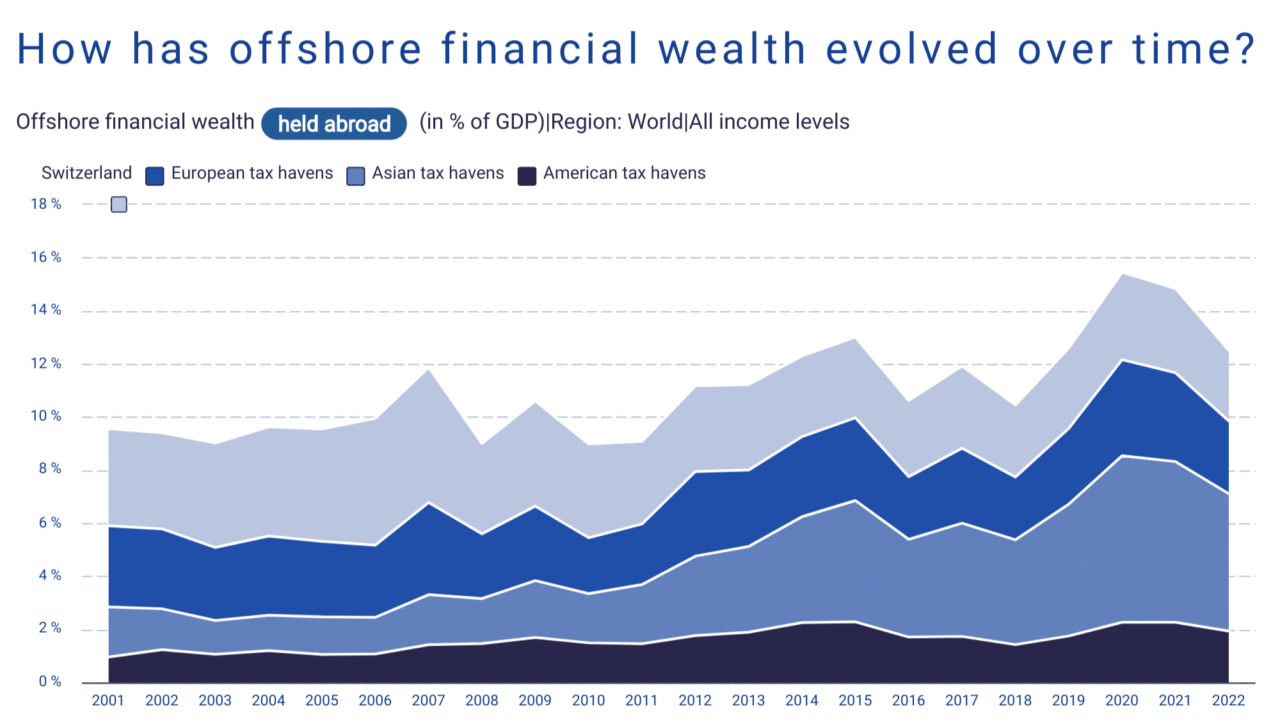

In 2022, according to the Global tax evasion report 2024 the financial wealth held by households abroad amounted to around $12,000 billion, equivalent to 12% of global GDP.

Over the past two decades, it has evolved at roughly the same speed as GDP, with annual fluctuations reflecting changes in asset prices (with, in particular, the years of strong financial market growth in 2020 and 2021).

Global offshore financial assets 2001-2022

Source Atlas of the Offshore world, European Tax Observatory The tax havens considered are specified in the Global tax evasion report 2024 (p. 23). – European tax havens (excluding Switzerland): Cyprus, Guernsey, Jersey, Isle of Man, Luxembourg, Belgium, United Kingdom. – Asian tax havens: Hong Kong, Singapore, Macao, Malaysia, Bahrain, Bermuda and Netherlands Antilles. Asian tax havens: Hong Kong, Singapore, Macau, Malaysia, Bahrain, as well as the Bahamas, Bermuda and the Netherlands Antilles. – American tax havens: Cayman Islands, Panama and the USA.

The growing transparency and exchange of information implemented on an increasingly systematic basis from the mid-2010s onwards(see section 2.3) has therefore not had a massive effect on the amount of household wealth held abroad, while tax evasion has largely declined (see next section).

This suggests that offshore asset ownership today is not just about tax evasion. Indeed, offshore financial institutions can also offer investment services that are not available in the customer’s home country or are available at a higher cost (such as brokerage services, wealth management or access to certain investment funds); they can enable customers to circumvent certain regulations (such as exchange controls) or help to conceal assets (from their spouse in the event of divorce, from business partners in the event of bankruptcy, from regulators for the financing of political parties). Tax havens can also be used to launder the proceeds of illegal activities.

The end of banking secrecy has led to a significant reduction in tax evasion by wealthy individuals.

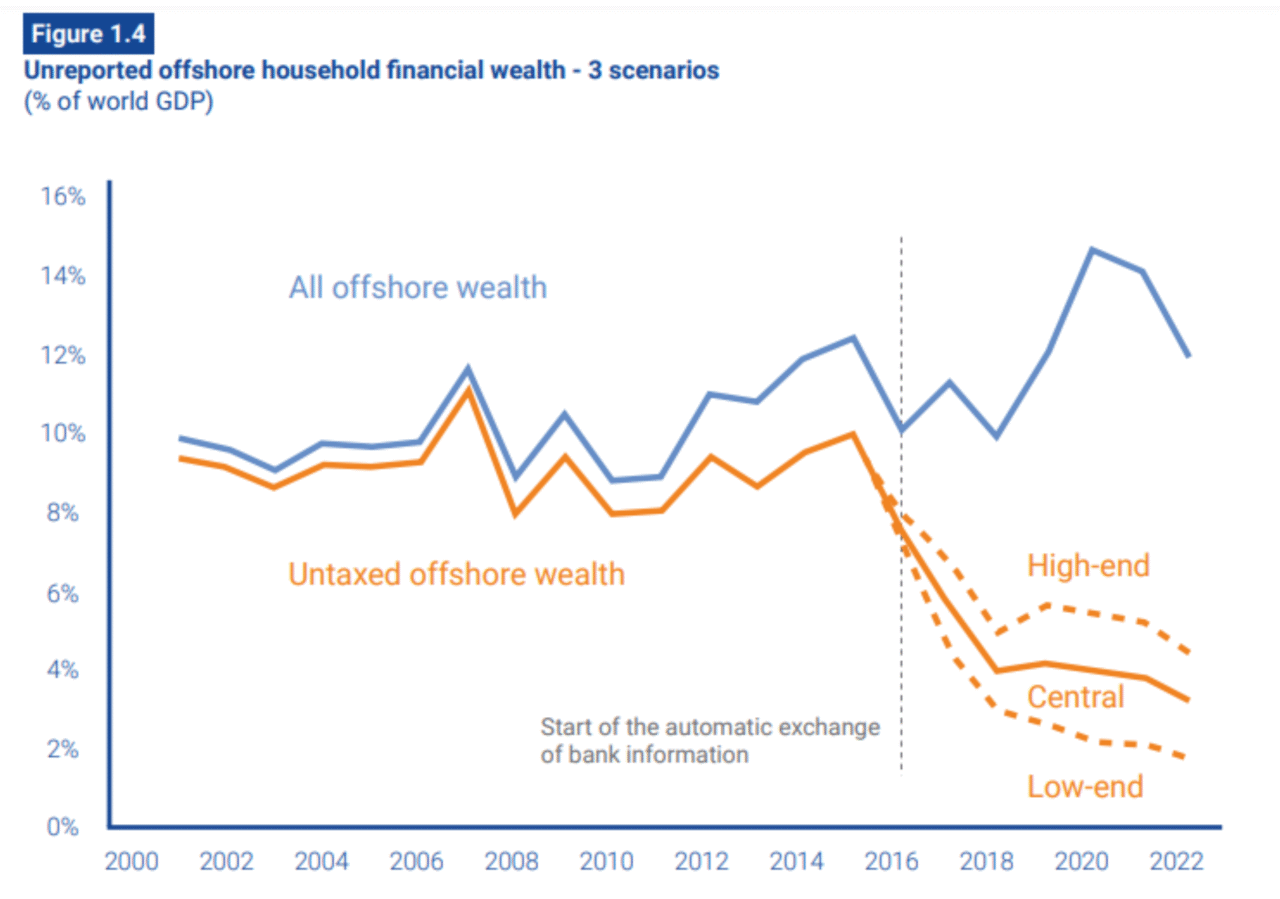

According to the Global tax evasion report 2024 before 2010, around 90% of offshore wealth was not declared by taxpayers.

The introduction of automatic information exchange from the mid-2010s onwards has led to a significant reduction in tax evasion via offshore centres.

In the book in which he recounts the epic battle against international tax evasion waged within the OECD 22 Pascal de Saint-Amans recounts how, following the collapse of banking secrecy, many tax evaders spontaneously denounced themselves to their country’s tax authorities.

“To the surprise even of governments the success is massive. In 2014, 37 billion euros in taxes were collected by more than 20 countries. This rose to 48 billion in 2015 and 93 billion in 2018. The 100 billion mark will be reached in 2019 (by the end of 2022, 114 billion), with over 500,000 people having regularized their situation. France represents a good tenth of the global figure, with nearly 10 billion collected and 50,000 people having gone to confession…”

Key stages in the automatic exchange of banking information

Most countries in the world follow the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard, with the notable exception of the United States, which has developed its own system.

2010 – U.S. Congress passes the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) 23 ), which requires financial institutions around the world to disclose information to the U.S. tax authorities about U.S. citizens who open accounts with them, or face penalties. The implementation of FATCA required the signing of bilateral agreements between the United States and numerous countries, which took place over the following two years.

2013 – The G20 mandates the OECD to develop a reporting standard for the automatic exchange of tax information.

2014 – Start of effective implementation of FATCA ;

The OECD has adopted the Common Reporting Standard (CRS). Under this scheme, financial institutions in participating countries (and territories) must report all accounts held by foreigners to their respective tax authorities. The latter then share this information on an annual basis with the tax authorities of the account holders’ home countries.

2017 – First exchanges of information within the CRS framework: 49 jurisdictions participate. 24

2024 – More than 120 jurisdictions are involved in the CRS program.

The experts at the European Tax Observatory have developed a methodology for estimating the proportion of offshore finance not reported to tax authorities. In their central scenario, this share has fallen from around 90% in the early 2010s to less than 30% today.

Wealth concealed offshore by households

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory

More needs to be done to combat tax evasion by wealthy individuals

Part of offshore financial wealth still escapes taxation

There are several reasons for this 25 :

- Factors linked to the limitations of the existing system: loopholes in the Common Reporting Standard; lack of administrative capacity to supervise and control the process in certain developing countries in particular Furthermore, the fact that the USA has its own information exchange system, different from the CRS, leaves a few loopholes open for taxpayers to exploit.

- Factors linked to non-compliance: non-declaration of certain financial assets or foreign clients by financial institutions betting on maintaining their offer of opaque services; taxpayers using complex international ownership structures (shell companies, foundations or trusts located in several jurisdictions around the world) or purchasing false nationality to preserve their anonymity and camouflage assets.

The automatic exchange system applies only to financial assets

Other types of assets (gold, works of art) and in particular offshore real estate are not covered by the automatic exchange of information.

As the OECD report points out Enhancing International Tax Transparency in the Real Estate Sector (2023), research on this subject shows that “the holding of real estate abroad has increased significantly over the last decade and (…) that this increase can be explained in part by a shift away from financial assets towards real estate assets”, in particular with a view to circumventing the CRS.

It should be noted that real estate, like financial assets, can be the subject of complex arrangements: direct ownership of real estate by a resident of another country, indirect ownership via a company or a trust (which sometimes means that properties that appear to belong to foreigners are in fact owned by residents).

Based on initial estimates for six territories (London, Paris, Singapore, Dubai, Côte d’Azur and Oslo) 26 500 billion, or over 10% of the total value of real estate in these areas.

Billionaire tax evasion also occurs (and increasingly so) at national level

Billionaires generally hold a substantial proportion of their financial assets in the form of company shares. To avoid paying tax on dividends, many billionaires place the ownership of their shares in a family holding company. In France and many other countries, these holdings benefit from the parent-daughter regime, which exempts them from paying tax on dividends. Although this system was originally designed to avoid double taxation of dividends 27 in practice, it can result in zero taxation.

As intra-group dividends are not taxed, profits can accumulate in the holding company, which does not need to distribute them. Individual shareholders can choose to distribute a small stream of income to themselves, sufficient to cover their private consumption expenditure, or borrow money to finance this consumption, thus avoiding dividend tax altogether. Insofar as these schemes are most often created to avoid dividend tax, they are indeed tax avoidance.

Some countries, the United States in particular, have introduced provisions in their tax code that make this type of arrangement impossible, by subjecting dividends earned through personal holding companies to income tax. Some American billionaires then choose to ensure that the companies in which they are the main shareholders do not distribute dividends 28 .

For more information on this subject, please consult chapter 4 of the Global tax evasion report 2024 .

Corporate tax evasion: transferring profits to tax havens

A multinational corporation (MNC) is a group of companies located in at least two countries. The “parent company”, the group’s official headquarters, designs and decides on the group’s worldwide organization and strategy. It controls a greater or lesser proportion of the capital (at least 10%) of the subsidiaries, which are nonetheless usually operationally autonomous. At the end of 2010, there were nearly 80,000 multinationals, with almost 800,000 subsidiaries. 30 Because they operate in different countries, multinational companies can exploit loopholes and differences in national tax legislation to minimize the amount of tax they pay.

In a note on international corporate taxation in 2019, the Conseil d’analyse économique drew a stark conclusion: the tax system is simply not adapted to multinationals.

“The current system of international corporate taxation, inherited from the early 20th century, is outdated. It allows multinational companies to exploit the complexity, loopholes and inadequacies of international tax rules for tax optimization purposes, and to transfer their profits to low- or no-tax jurisdictions.”

The main principles of international corporate taxation

At the beginning of the 20th century, with the growth of multinationals came the question of double taxation of their profits. 31 In 1924, the authors of a report on this subject commissioned by the League of Nations set out three principles, which for over a century formed the pillars of international corporate taxation.

Corporate income tax is paid to the government of the country where the business is carried on (and not to the country of the owner(s) of the company’s capital).

Arm’s length pricing addresses the problem posed by the fact that the activities of the various companies making up a multinational are intertwined. For example, production may be carried out by a French subsidiary and then exported to the United States, where the parent company will handle marketing, sales and distribution. In this case, the two companies must calculate their profits separately, as if they were not linked: the products traded between them must be valued as if they were sold on the world market.

International tax issues should be dealt with bilaterally, not as part of a global multilateral agreement. Thousands of “double taxation agreements” following these general principles have been signed between countries since the 1920s.

While the shortcomings of these three principles were denounced from the outset, the decline of globalization in subsequent decades made the issue less central. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the situation began to change, until the beginning of the 21st century, when a growing number of tax scandals revealed the extent of tax evasion by multinationals. The subject of appropriate taxation then returned to the heart of international negotiations.

Source Gabriel Zucman, Taxing Across Borders: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2014.

How does profit transfer work?

Profit transfer is different from business relocation

It’s not a question of locating the company’s activity in low-tax countries, but rather of recording profits in countries where they are taxed little or not at all, without this being justified by any real economic activity in the country in question.

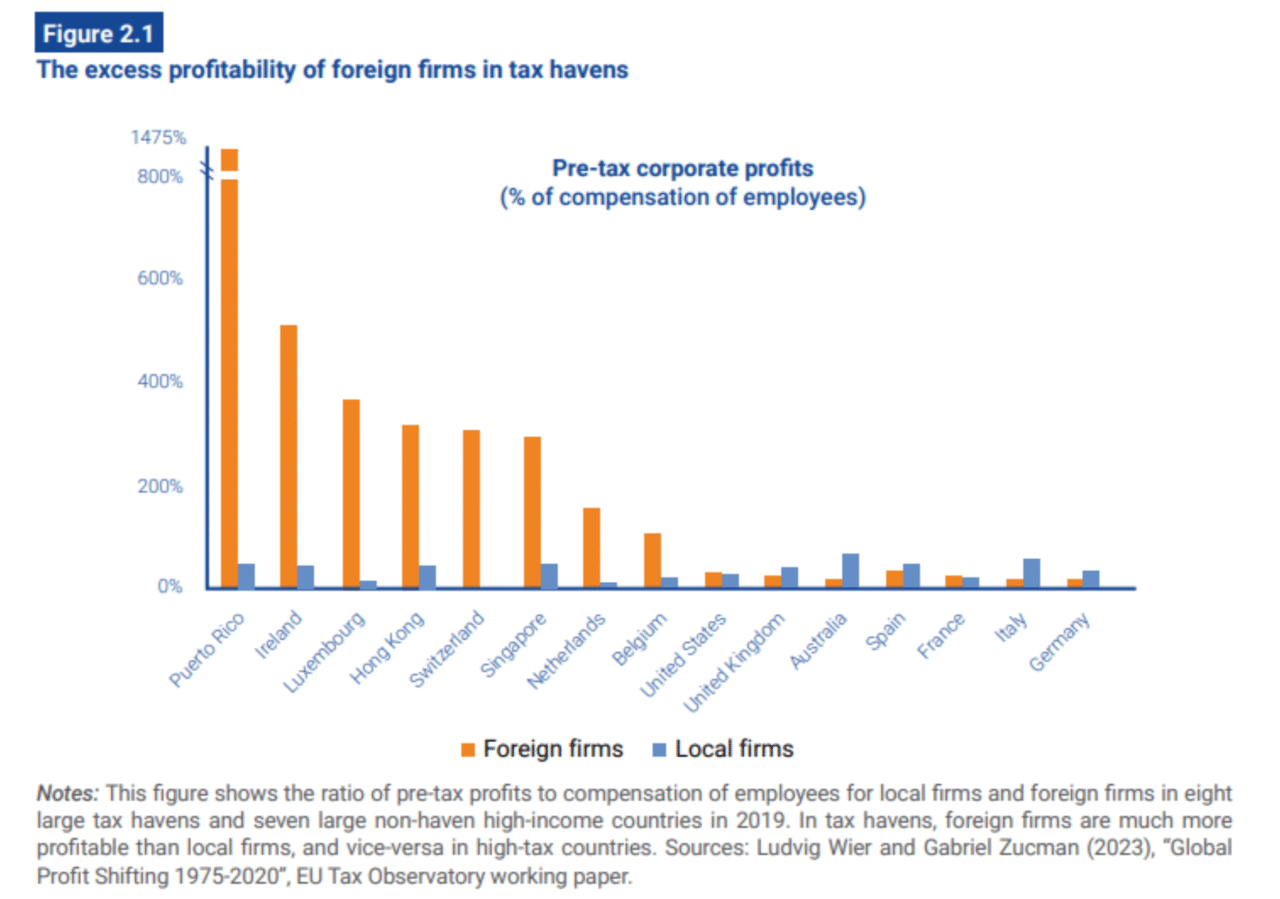

The following graph, taken from the work of Gabriel Zucman, clearly illustrates this point. It compares the ratio of profits to wages paid by foreign and local companies in different countries.

Excessive profitability of foreign companies in tax havens

Reading: In Puerto Rico, the ratio of profits to wages for foreign companies (in orange) is close to 1500%. This means that for every dollar of wages paid, they generate an average of nearly $15 in profits. The ratio for local companies (in blue) is close to 50%.

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory

As can be seen, in tax havens (on the left of the graph), foreign companies are clearly more “profitable” than domestic ones. Conversely, in other countries (on the right of the chart), foreign companies appear to be less profitable than domestic ones. This may be explained by the fact that part of their profits have been transferred to tax havens.

Three main types of mechanisms for transferring profits to tax havens

Of course, the extremely complex legal and financial arrangements 33 often combine all three mechanisms (e.g. double Irish and Dutch sandwich structures). 34 ).

Manipulating transfer prices (intra-group export and import prices)

Multinationals are made up of a parent company and subsidiaries that trade with each other: they can therefore manipulate the prices of goods and services that the various companies in the group trade with each other.

For example, subsidiaries located in high-tax countries can export goods and services at low prices to related companies in low-tax countries, and import them at high prices. This has the effect of shifting income from the high-tax country to the low-tax country, and thus minimizing the overall taxes paid.

The aim of the arm’s length principle (see box above) was precisely to prevent this type of manipulation: intra-group transactions are supposed to be carried out at market prices, as if the two parties were independent. In practice, this principle comes up against a number of limitations. On the one hand, intra-group trade accounts for a very large proportion of international trade. 35 This makes it difficult for national tax authorities to monitor all these transactions. Secondly, market prices often simply do not exist: this is particularly true of intangible assets.

Locate intangible assets (trademarks, patents, logos, algorithms, financial portfolios) in tax havens and invoice subsidiaries in high-tax countries for the right to use them. The corresponding payments reduce profits in high-tax countries and increase them in tax havens.

Intra-group loans: subsidiaries in high-tax countries can borrow money (potentially at relatively high interest rates) from subsidiaries in low-tax countries.

Profit transfer: what’s the scale, who benefits, who suffers?

Multinational tax evasion took off fifty years ago

In the mid-1970s, multinationals began transferring their profits to tax havens.

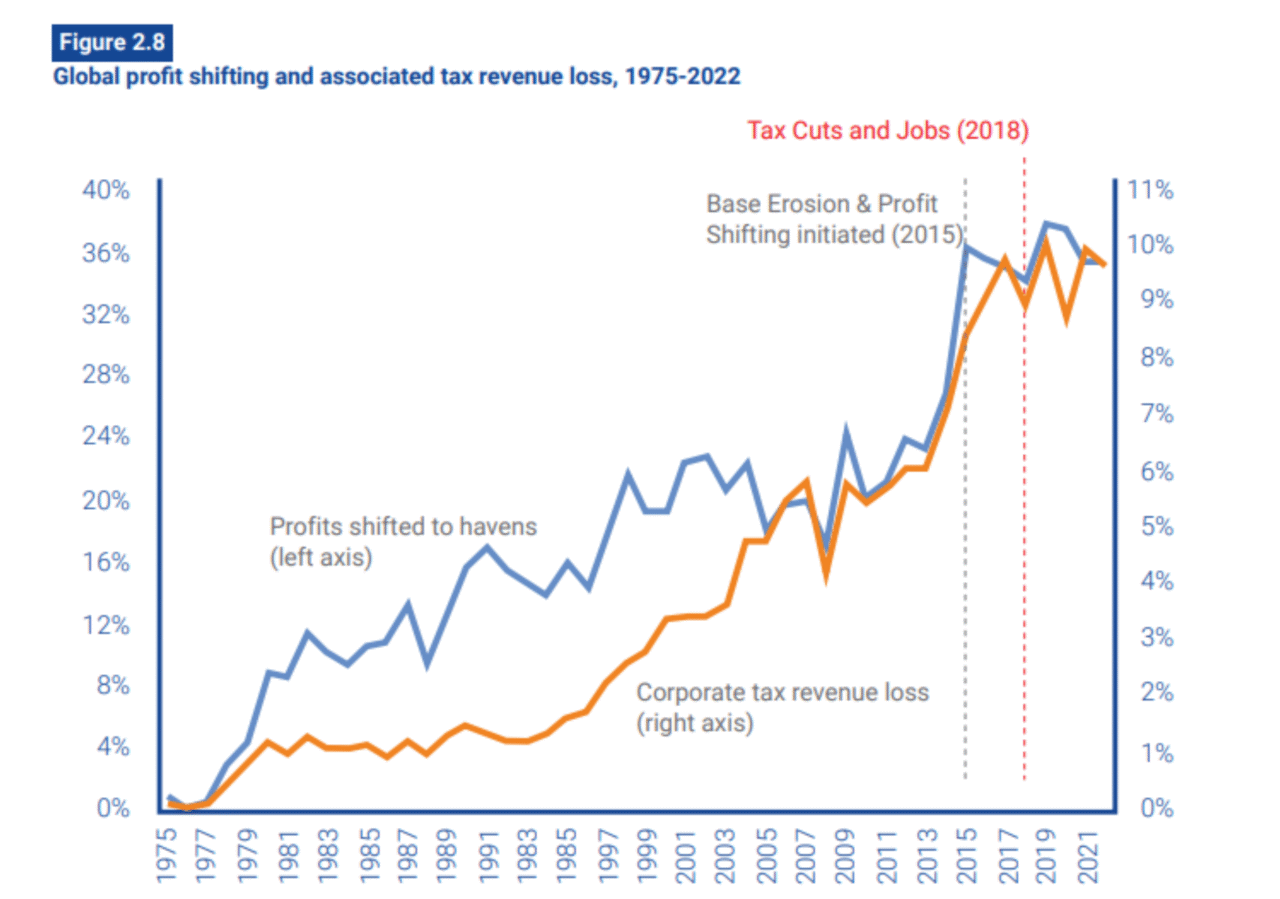

Global profit shifting and associated tax revenue losses, 1975-2022

Reading: Since 2015, around 35% of profits earned abroad 36 by multinationals (blue line, left axis) are transferred to tax havens. Depending on the year, this represents a loss of tax revenue corresponding to between 8% and 10% of income tax receipts (orange line, right axis).

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory

The launch in 2015 of the BEPS process under the aegis of the OECD and the adoption of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the USA, initiatives designed to combat profit shifting(see section 3.3.3), do not appear to have had any major impact to date. However, the authors of the Global tax evasion report note a slight reversal in trends: whereas in the early 2010s, profits registered in tax havens were growing faster than foreign profits, this is no longer the case after 2015.

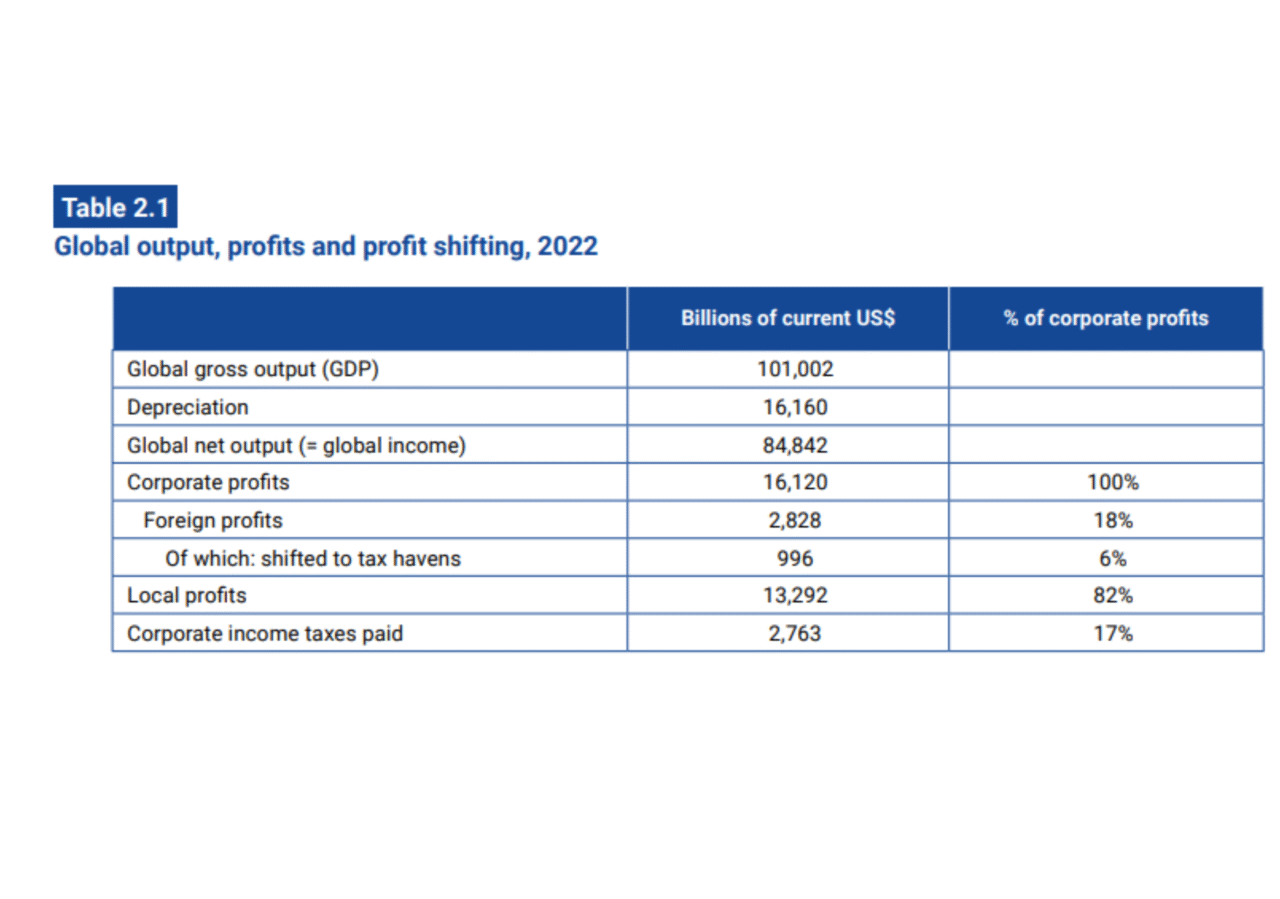

What is the ratio of profits transferred to tax havens to total corporate profits?

The following table illustrates the transfer of profits at the level of all companies. In 2022, corporate profits amounted to $16,120 billion worldwide, of which 82% were local and 18% foreign. 36

Global GDP, corporate profits and profit transfers

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory

Note: the main tax havens considered are those mentioned in the other charts in this section. The full list can be found in the article by The Missing Profits of Nations by Thomas Tørslov, Ludvig Wier, and Gabriel Zucman in the Review of Economic Studies.

Several lessons can be drawn from this table.

- The fact that 82% of profits are declared locally (i.e. in the country of head office) highlights the fact that most companies are not multinationals and therefore cannot afford to transfer their profits to tax havens.

- Around a third (nearly 1,000 billion) of the profits made by multinationals outside their country of headquarters are transferred to tax havens, showing that they make extensive use of them.

Which countries are the winners and losers when it comes to transferring profits to tax havens?

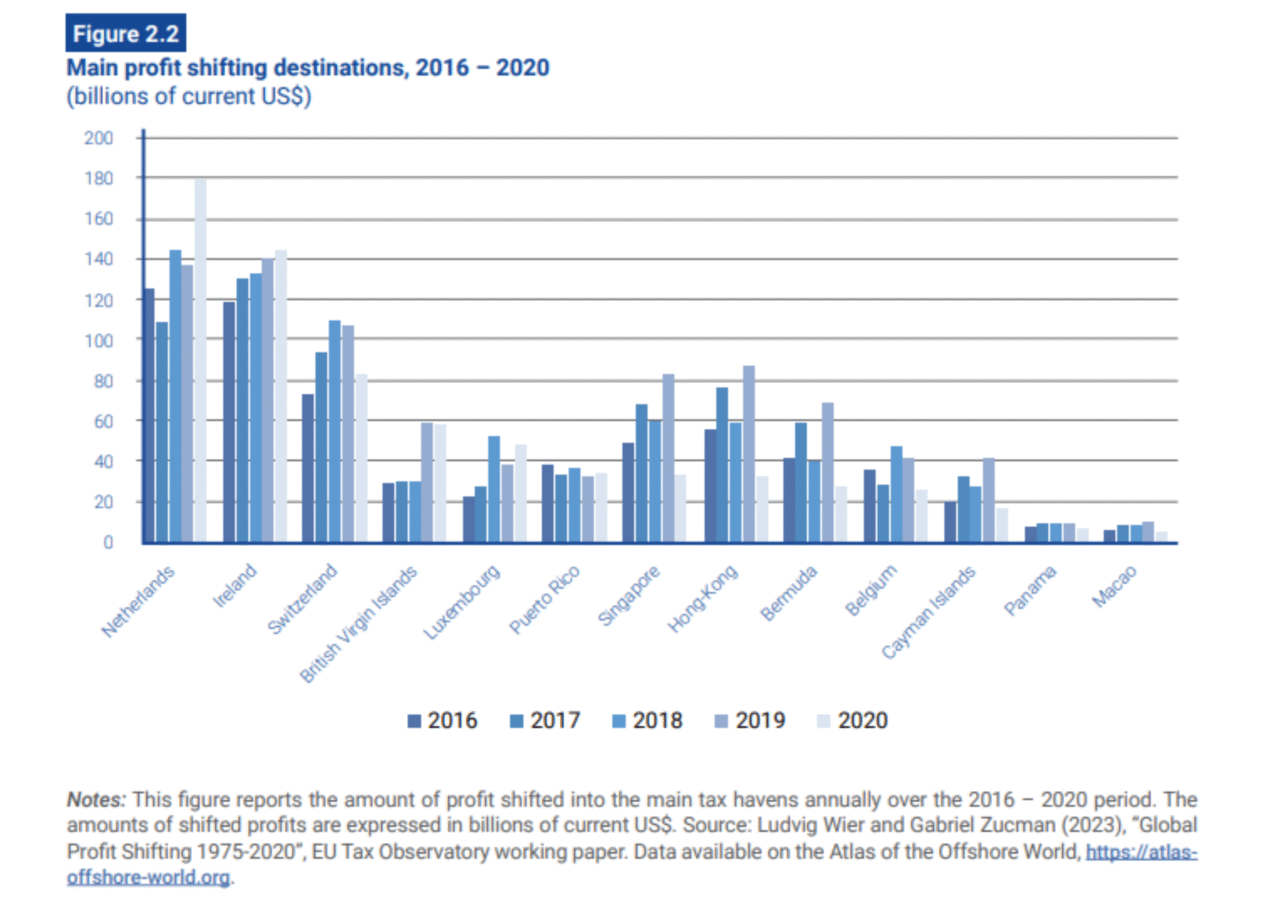

Thirteen countries are the preferred destinations for multinationals to transfer profits.

Top destinations for multinational tax evasion 2016-2020

Reading: in 2020, profits transferred to the Netherlands amounted to almost $180 billion.

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory and Atlas of the Offshore world

As can be seen from the graph above, five of the main tax havens are located on the European continent (or territories belonging to a European country in the case of the British Virgin Islands), and 3 are EU members. In particular, Ireland and the Netherlands each account for around 15% of profits transferred each year.

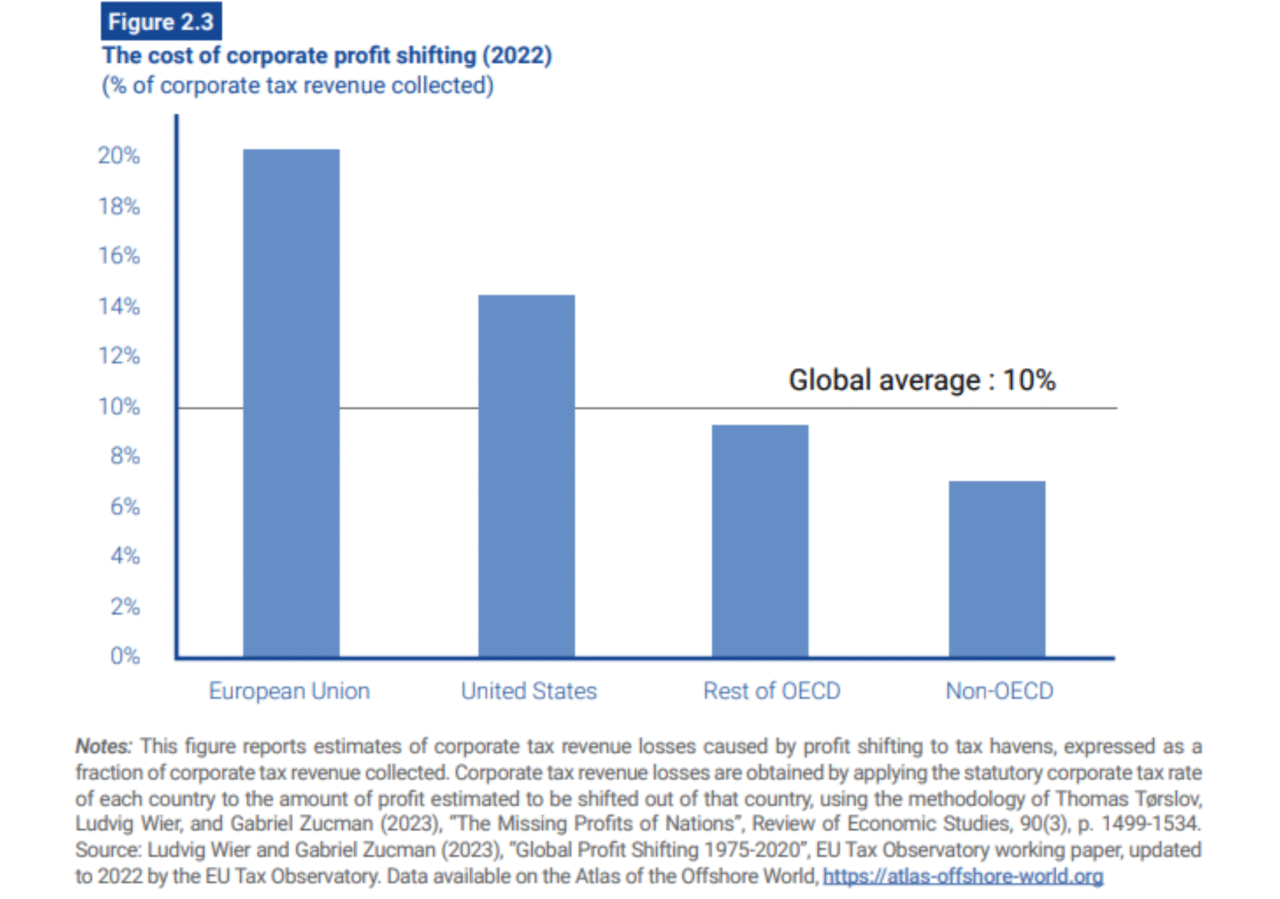

The situation is all the more absurd in that the countries of the European Union are among the biggest losers. While the global average for revenue losses is around 10%, it is close to 20% in the EU.

While tax losses in developing countries are smaller (in proportion and amount), they have a major impact on the quality of life of their populations, as public revenues in these countries are heavily dependent on corporate income tax.

Tax losses due to corporate tax avoidance in 2022 by geographic region

Source Global tax evasion report 2024, European Tax Observatory and Atlas of the Offshore world

Legislative developments

Faced with the evidence of the scale of tax evasion by multinationals, the international community has finally reacted.

the BEPS project

At the instigation of the G20, the OECD launched the BEPS(Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project to combat tax base erosion and profit shifting.

Key stages in the BEPS project

April 2009 – The London G20 Final Declaration marks the start of international tax mobilization(see quote in section 1.3).

February 2013 – Publication of the report Combating tax base erosion and profit shifting commissioned by the G20 from the OECD.

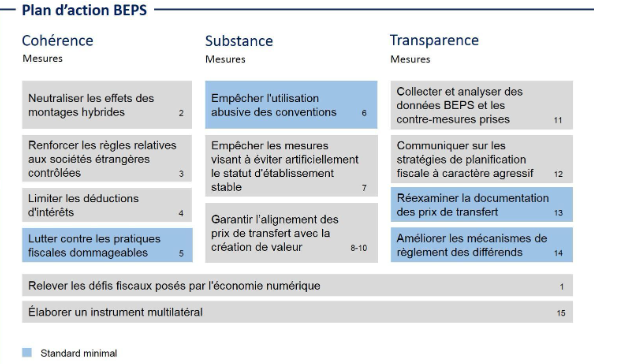

September 2013 – OECD and G20 countries agree to draw up the BEPS Action Plan, which identifies 15 actions to harmonize national rules affecting transnational activities, strengthen “substance” requirements in existing international standards, and improve transparency and legal certainty.

November 2015 – At the G20 Antalya the heads of government approve the BEPS package including the reports responding to the 15 actions.

2016 – Launch of the “OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS” aimed at opening up the process beyond G20 and OECD countries. By May 2024, more than 145 countries and jurisdictions are members of the Inclusive Framework (up from 82 at the inaugural meeting in June 2016 in Japan).

Find out more about the history of BEPS in the book Tax havens. How we changed the course of history (2023) by Pascal Saint-Amans.

View all documents produced by the OECD as part of the BEPS project

The BEPS project aims to combat tax evasion, improve the consistency of international tax rules and ensure a more transparent tax environment. It comprises 15 actions to be implemented by the more than 140 countries and jurisdictions that have signed up to the BEPS Inclusive Framework (see box). For four of these actions, minimum standards must be implemented.

The Inclusive Framework is thus a forum for exchange and collaboration on the development of international tax standards, as well as a forum for peer review of each country’s application of the package of measures, and in particular the minimum standards.

focus on country-by-country reporting

As part of action 13 of the BEPS multinationals with consolidated sales of over €750 million must prepare and submit to the tax authorities a country-by-country report containing data on the worldwide distribution of income, profits, taxes paid and economic activity within the tax jurisdictions in which they operate. This makes it possible to identify any discrepancies between activities, profits and taxes paid.

By 2022, nearly 120 jurisdictions have a law introducing such a reporting obligation. This covers virtually all multinationals with sales in excess of €750 million.

Individual reports are not made public (except for banks in the European Union, which are obliged to do so, and companies which do so on a voluntary basis). However, the OECD publishes aggregate data by country. The European Tax Observatory has compiled them in a country-by-country data explorer available to the general public.

Focus on the 15% minimum tax

The main success was achieved in Action 1 “Tax challenges posed by the digitization of the economy”.

By October 2021, nearly 140 countries and jurisdictions adopted the Declaration on a two-pillar solution to the tax challenges raised by the digitization of the economy 37 and its action plan.

It is the second pillar that has generated the most hope and media coverage. For the first time in history, an international agreement establishes a worldwide minimum corporate tax.

The countries of the inclusive framework have agreed on the principle of global rules against tax base erosion (the “GloBE rules”). 38 aimed at ensuring that large multinational companies pay a minimum level of tax on their income in every jurisdiction where they operate. The report presenting the GloBE rules rules was adopted by the Inclusive Framework countries in December 2021. 39

Several countries have subsequently transposed these rules into national law. 40 This is the case in the European Union with Directive 2022/2523 (see the transposition for France on the tax site ). However, this is not the case in the United States, which would have to amend the provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act adopted in 2017, which introduces a minimum tax on US multinationals (albeit under a less ambitious system).

The general principle of the 2021 agreement is that multinational companies with consolidated sales of €750 million or more must pay a minimum effective rate of 15% on consolidated profits.

All countries, or tax jurisdictions, are thus encouraged to implement such a minimum tax rate.

If a country fails to do so, the agreement provides for two mechanisms to ensure that profits are still taxed.

- IRR(Income Inclusion Rule): if a jurisdiction refuses to introduce a national minimum effective tax rate of 15%, the country in which the parent company is headquartered can collect the difference between the effective tax rate paid in the jurisdiction in question and the minimum 15% rate.

- UTPR(Under Tax Payment Rule): if the headquarters country refuses to apply the IRR, the signatory countries to the agreement can tax part of the untaxed profits themselves. At the request of the United States, this rule has been suspended until 2026.

A number of derogations subsequently introduced have reduced the scope of the initial agreement.

Substance exclusions“.

Companies with a real activity in a low-tax country can exclude a certain amount of profits from the minimum tax base. As the European Tax Observatory explains so well, this provision is an incentive to relocate economic activity for tax reasons. Moreover, it reflects “the idea that tax competition, if it is real (companies relocating their production to low-tax countries), is legitimate, or at least does not need to be regulated by international agreements. The only thing that is not legitimate, according to the view underlying this exemption, is the artificial transfer of profit.” 42

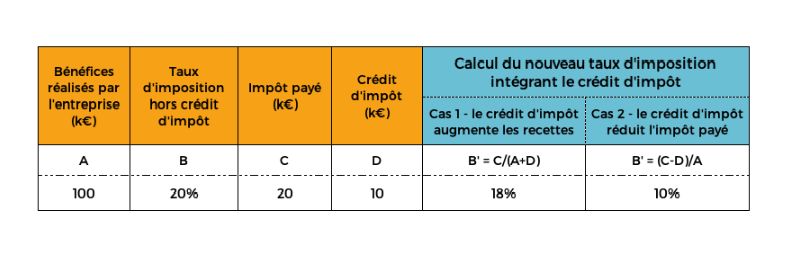

Excluding tax credits

Tax credits are not considered as a reduction in tax paid, but as an increase in revenue. This choice has consequences for the reality of the minimum rate at 15%, as shown in the example below.

In the first case, the 15% minimum tax rule seems to have been respected, so the company has nothing further to pay. In reality, it’s the second case that best reflects the economic reality: the company has €90k of after-tax income at its disposal, which it can distribute to shareholders or reinvest. To remain tax havens, the governments of these countries simply need to restructure their tax policies, offering generous tax credits rather than low tax rates.

Effectively combating tax evasion is a question of political choices

This exploration of the opaque and voluntarily complex world of tax havens and tax evasion leads to a number of observations. The first is positive: the end of banking secrecy, the denunciation of tax havens, a minimum tax on multinationals… Remarkable advances, previously considered utopian, have recently taken place. These developments show not only that tax cooperation is possible within the international community, but also, as the European Tax Observatory points out, that “tax evasion is not a law of nature, but a political choice”.

However, there is still a long way to go to put an end to tax evasion by the most powerful individuals and companies. The last decade has shown how, in the face of new regulations, these players adapt and develop new strategies to maintain their tax privileges. While all the ingredients for the development of opaque offshore finance were in place at the beginning of the 20th century, it was globalization and the liberalization of capital markets that enabled the phenomenon to take on its full scope. Without intervention in this area, it will probably be difficult to eradicate these practices. Finally, beyond tax evasion, it is the question of international tax competition that should now be at the heart of the debate.

Find out more

Books, comics, documentaries

- Le triomphe de l’injustice, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, 2019, Éd. Seuil

- Tax havens. Comment on a changé le cours de l’histoire, Pascal Saint-Amans, 2023, Ed. Seuil.

- L’évasion fiscale, toute une histoire, Attac France, 2024

- Tax havens, Christian Chavagneux, Ronen P. Palan, Ed. La Découverte, 2017

- Tax Wars documentary, Arte, 2024

Committed players

Atlas, tools and graphics

- See, for example, L’évasion fiscale, un sport très prisé avant 1914, Alternatives Economiques (15/12/2016) ↩︎

- See missingprofits.world, the atlas based on the work of Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Tørsløv and Ludvig Wier The Missing Profits of Nations, Review of Economic Studies, 2023. ↩︎

- 40% of multinationals’ profits are relocated to tax havens, Opinion column by Gabriel Zucman, Le Monde (07/11/2017) ↩︎

- The European Commission’s services estimated that in 2019 the “VAT gap” represented 134 billion in lost tax revenue, including almost 15 billion for France. The VAT gap is obtained by calculating the difference between the VAT revenue actually collected and the revenue that should have been collected based on consumption figures. There are four main reasons for this gap: VAT fraud; VAT avoidance and tax optimization practices; bankruptcy and financial insolvency; and administrative errors. Source: VAT gap in the EU, Report 2021, DG TAXUD, European Commission. ↩︎

- La fraude aux prélèvements obligatoires, Cour des Comptes, 2019 ↩︎

- European Commission Communication 2015/0136 on tax transparency to combat tax fraud and tax evasion ↩︎

- Examples in France: donations to non-profit organizations, research tax credits, investments in real estate, in the capital of SMEs, employment of home workers, VAT rate reductions on certain activities, etc. ↩︎

- other ↩︎

- UBS, Crédit Suisse, HSBC, Société Générale, Crédit Agricole, BNP… See the report Usual Suspects? Co-conspirators in the business of tax dodging, Ben Schumann for the Green Group in the European Parliament, 2017 ↩︎

- These are EY, Deloitte, PwC and KPMG. See Chris Jones, Yama Temouri, Alex Cobham, Tax haven networks and the role of the Big 4 accountancy firms, Journal of World Business, 2018. In addition, the lobbying carried out by these players against greater tax transparency in the Accounting for influence report, Corporate Europe Observatory, 2018 ↩︎

- Vincent Piolet, Paradis fiscal : combien de définitions, Recherches internationales, 2014 ↩︎

- What was the point of the OECD’s black and grey lists?, CCFD Terre Solidaire, 2021 ↩︎

- These are anti-BEPS measures, named after the action plan to combat tax evasion developed under the aegis of the OECD. See section 3.3 ↩︎

- European Parliament resolution of January 21, 2021 on the reform of the European Union’s list of tax havens ↩︎

- See Gabriel Zucman, Annette Alstadsæter and Niels Johannesen Tax Evasion and Inequality, American Economic Review, 2019 ↩︎

- This applies not only to corporate income tax, but also to other types of levy, such as production taxes. See the chapter “Companies pay taxes and receive public funding” in the module on business in the Anthropocene era. ↩︎

- Tax havens at the heart of the markets, Alternatives Économiques (28/10/2021); see also Christian Chavagneux, Sortir les banques des paradis fiscaux, Revue d’économie financière, 2017 ↩︎

- Global tax evasion report 2024 ↩︎

- Base Erosion and Profit Shifting ↩︎

- To find out more, see the website of the Ad Hoc Intergovernmental Committee on Taxation and the article Why the world needs a global tax treaty in ONUinfo(31/08/24), which gives details of the vote. ↩︎

- Bank deposits and securities portfolios: shares, bonds, mutual fund units, etc. ↩︎

- Tax havens. How we changed the course of history Pascal Saint-Amans, Seuil, 2023 ↩︎

- See the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) page, on the official website of the Internal Revenue Service (Accessed on 09/13/24) ↩︎

- Automatic exchange of information (AEOI): status of commitments– Last update: 23 April 2024 ↩︎

- Numerous examples and references in the Global tax evasion report 2024 (pages 30 and 31). ↩︎

- See Annette Alstadsæter, Matt Collin, Karan Mishra, Bluebery Planterose, Gabriel Zucman, and Andreas Økland Towards an Atlas of Offshore Real Estate: Estimates for Selected Areas and Cities, working paper, 2023 ; and Atlas of the offshore world ↩︎

- The first time when the dividend is paid by the subsidiary to the parent company, and the second time when the parent company pays dividends to individual shareholders. ↩︎

- This is the case, for example, of Warren Buffett, principal shareholder of Berkshire Hathaway, a listed company that has never paid a dividend. ↩︎

- Insee gives this definition of a multinational company: “a multinational firm is a group of companies with at least one legal unit in France and one abroad” (See theCompany module). ↩︎

- L’ampleur et les formes de la mondialisation des entreprises, Mouhoub El Mouhoud, chapter in his Que sais-je ? Mondialisation et délocalisation des entreprises La Découverte, 2017 ↩︎

- Profits made by a subsidiary could be taxed in the country where the subsidiary is located and in the country of the parent company. ↩︎

- League of Nations Report on Double Taxation Submitted to the Financial Committee by Professors Bruins, Einaudi, Seligman, and Sir Josiah Stamp, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 1924 ↩︎

- For detailed historical examples see by Gabriel Zucman, Taxing Across Borders: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2014 ↩︎

- See this simple explanation from Finance pour Tous with the example of Apple: Tax optimization circuits that pass through Europe (07/04/2016) ↩︎

- According to UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2013 (chap IV, figure IV.14 and Box IV.3), intra-group trade accounted for 30% of world trade in 2010 (in terms of gross exports). ↩︎

- Foreign profits” are those earned by multinational companies outside their home country. They include, for example, profits recorded by Meta outside the United States, by Bayer outside Germany or by TotalEnergies outside France. ↩︎

- The declaration was adopted in July 2021; the October 2021 version also includes a detailed implementation plan. ↩︎

- GloBE rules are intended to be implemented as part of a “common approach”. This means that a jurisdiction choosing to adopt these rules (and thus transpose them into its national law) must do so in a manner consistent with the common rules. On the other hand, a jurisdiction that chooses not to implement these rules is still expected to accept their application by other jurisdictions in relation to multinationals operating on its territory. Source on the OECD website. ↩︎

- The OECD has produced a number of interpretative documents that can be downloaded from its website , including an implementation manual, commentaries and administrative instructions. ↩︎

- See the map of Pillar 2 domestic implementation ↩︎

- In the first year, this amount is equal to 8% of the value of tangible assets and 10% of payroll. The rates then decrease steadily over time, reaching 5% of tangible assets and 5% of payroll after 10 years of implementation. ↩︎

- Global tax evasion report 2024, p.52 ↩︎