This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

Economic activity (purchasing, production, distribution, sales, consumption, waste management) is largely carried out through monetary transactions, where the good or service sold and purchased is at a price accepted by both buyer and seller. In this section, we’ll look at how markets function, enabling these transactions and the setting of prices. We will also outline the properties and limits of markets, and the role of public authorities in their emergence and regulation.

The ability of markets to set prices, and the role these prices play in “doing business”, is a remarkable property. But there’s no such thing as an “invisible hand”, and it’s dangerous to attribute magical properties to the market. 1 Contrary to popular belief 2 markets do not spontaneously balance themselves. We’ll be taking a look at the flaws in this process, known as “market failures”. 3 We will then see that, in the face of today’s immense challenges, such as climate change :

- Public intervention to regulate markets is legitimate and necessary.

- Prices (possibly resulting from monetarization by public authorities) 4 ) cannot be the only signals 5 and the only constraints envisaged to modify behavior and bring about social change. The role of law, regulations, morality and a sense of responsibility towards fellow human beings and society cannot be forgotten.

- Work on companies and the commons shows that alternative or complementary institutional arrangements are needed at all levels.

This module benefited from proofreading and comments by Florence Al Talabani and Yannick Saleman.

The essentials

A few key concepts to understand the market(s)

A few definitions

In this module, we’ll look at the “market” from three different perspectives, which are worth keeping in mind. One is empirical, focusing on the organization and regulatory framework of markets as they occur in the real world. These organizations have one thing in common: they enable a seller or buyer to identify counterparties to the desired transaction, while at the same time having access to information on similar transaction conditions, in particular prices. The second perspective is that of the discipline of economics, for which the market is a privileged object of analysis and theorization, with significant divergences between schools of thought. The third is the “market” as a political principle, which has become dominant since the early 90s, ordering the economic system as opposed to centralized and/or directed economies. So let’s start with a few definitions.

Markets, in the empirical sense

Empirically, the term market can refer to :

- a place for physical exchange (like traditional markets where food and other products are bought and sold) or virtual exchange (like stock exchanges).

- all exchanges concerning a sector of the economy (real estate market, wheat market, etc.).

- all trade concerning a region (Chinese market).

We’ll see later that the functioning of these “empirical” markets is not spontaneous, but requires the intervention of public authorities (in terms of property law and competition law in particular), and we’ll see how economists have tried and are trying to understand this functioning.

Markets in the economic sense: liberal theory now dominant

This concept is based on an idealized vision of the market, and encourages its extension to all areas of life.

Since the early 1980s, political discourse and practice, underpinned by the theses of liberal economists such as Friedrich A. Hayek 6 have been pushing for the extension of the market sphere. The argument is as follows: the mechanism puts those directly concerned at the center of decision-making. Competition produces a price that reflects the relative scarcity of the good being exchanged, as well as the interest that people have in it, based on the information they have (or seek beforehand). This vision is based on the highly debatable postulate that economic players are “rational”.

The “producer” (farmer, industrialist, service company) is motivated to obtain the most accurate information possible on his customers’ needs, their willingness to pay, as well as on his own costs and their structure (fixed costs, variable costs), and his production methods. He can act to improve customer service, innovate, produce differently, etc. Consumers make their purchasing choices according to their desires, budget, etc. Hayek insisted that an administration cannot have the capacity to access all this information and process it correctly. From this he deduced a unilateral plea for the market as the most efficient institution.

However, neither the market, nor the authorities, nor anyone else can have all the right information at the right time. And, more to the point, information can be uneven between seller and buyer, which is one of the justifications for government intervention or other forms of coordination. We’ll come back to this in Essentials 3.1, on how markets work.

The market and competition principle as a political vision

The market is not just an empirical reality or, conversely, an object of academic study. It is also a political vision, and sometimes the object of quasi-religious belief. 7 With the birth of political economy came the idea – revolutionary at the time – of autonomy (Karl Polanyi 8 speaks of “disembedding”) of the economy and individual choices in relation to social and political relationships. From its very beginnings, “economic science” has had a normative, and therefore political, aim, and the case of the market is emblematic of this, as these few striking historical examples show.

From the 18th century onwards, economists played an active and effective role in major debates (Thomas Malthus in the debate on poor laws, David Ricardo in the debate on free trade) which had considerable political impact. The free trade pushed by David Ricardo for example, altered the balance of power between landowners and industrialists, and affected workers’ working conditions. The activism of neoclassical economists is permanent (even if its effects should not be overestimated). Using reasoning and mathematical models, they try to show that the optimum is indeed the market (correcting it, if necessary, for its failings). But such reasoning and models are hard to convince: they presuppose extremely strong simplifications of economic and social reality, on which their conclusions depend to a large extent.

This political character is manifested in the works of Karl Marx and his successors, and in the political takeover of economic levers, in the communist vision established in Russia from 1917 and in China under Mao.

The scale of the 1929 crisis (see Essential 5.2) was in part due to the aforementioned belief in the markets’ ability to restore equilibrium on their own. For months, despite the major economic crisis unfolding before their eyes, the authorities believed in “letting it happen, letting it pass“. 9

After the Second World War, the creation of the GATT and then the WTO, in parallel with the implementation of the common market and then the single market in Europe, made free trade (and therefore the generalization of the market) the economic ideal to aim for. This is obviously a political choice, and there are alternatives between generalized free trade and unilateral protectionism.

Since then, the main political parties in various countries (in Europe and in France, but everywhere in the world except in the Communist countries) have taken a stance on what should be market-driven and what should not. The dividing line is not technical but ideological, with some parties supporting maximum liberalization and privatization, while others favor planning and nationalization of certain businesses, including credit.

In France, the Commissariat Général au Plan, for the economy, and the DATAR, 10 for regional planning, had their heyday in the 80s. The turning point of 1983 led to their political marginalization. More generally, the 80s (the “Reagan and Thatcher years”), which followed the oil crises of the 70s, saw the intellectual and political domination of neo-liberal, highly pro-market ideas. Despite the financial crises, particularly those of 2008-2009, these ideas remain powerful.

A French organizational innovation is the creation of a General Secretariat for Ecological Planning in 2022. This organization makes perfect sense, as we show in this module: the market alone cannot take Nature into account. History will show whether this innovation will stand the test of time. But the debate surrounding this type of structure is a political one: the notion of “ecological planning” was launched by Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the Front de Gauche party in the 2010s, 11 and then taken up again by a President of the Republic claiming to be from the center-right 10 years later…

More recently, the “libertarians 12 in the United States, Donald Trump, and in Argentina, Javier Milei, want to abolish the state and public services, in defiance of their citizens and of what we demonstrate in this module: the market cannot do everything, and especially not everything for everyone. Libertarian policies can only benefit a caste that crushes the vast majority of citizens. These are not just devastating choices for social cohesion and Nature: behind these positions lies an ideology of “survival of the fittest” that is totally assumed , and total cynicism. Its zealots know full well that it is they who benefit, against all others… .

Trade structures the economy

Every day, billions of people, companies, associations and public administrations use a particular form of transaction – monetary exchange – which they decide autonomously. 13 These exchanges involve billions of products 14 of products, services, labor, natural resources, rights (e.g., intellectual property, infrastructure use) and financial assets. These exchanges distribute part of an economy’s total production between different uses, and redistribute claims and income, as well as the rights to exploit certain natural resources.

Taken together, these exchanges form the continuous flow of goods and services between producers and/or extractors of natural resources, and between the latter and consumers. They determine the primary distribution of income. 15

Markets are essential to organize trade

Markets enable these exchanges, regulate flows and contribute to the integration and coherence of different sectors of the economy. Without organized markets, transactions would depend on random encounters. Buyers and sellers would not be able to foresee and plan the transactions necessary for their activity, production, sale or consumption. They would have to discuss prices and negotiate constantly (which is done in some traditional markets, but not in “modern” economies, notably for legal reasons).

It’s worth noting that “markets”, like trade, originated well before the beginning of the first millennium BC, and elsewhere than in Europe. 16 The expansion of the market sphere accelerated with the Industrial Revolution and the division of labor, as well as during the successive phases of world trade expansion since the 19th century. It now seems impossible to do without such exchanges, initiated by both buyer and seller. Dictatorial or totalitarian regimes that have attempted to consolidate their power have failed. 17 On a political level, these attempts are aimed at suppressing a fundamental economic freedom: the ability not to depend on political power to feed oneself and satisfy one’s needs. What’s more, the products on offer were unsatisfactory in terms of both quantity and quality. 18 There were shortages, as well as untold wastage. On the other hand, the state is indispensable to the functioning of markets, if only to ensure that transactions are respected(see Essential 3).

As for the environment, it wasn’t taken into consideration either. 19 than in a capitalist system. But, conversely, favoring market transactions is no guarantee of a democratic political regime or shared prosperity. 20

The State decides what is marketable

In reality, in no country are all transactions monetary, nor do they all take place on established “markets” or “exchanges”. Non-market transactions may be based on interpersonal giving 21 redistribution, barter, public service or quantitative rationing by a central authority. 22 The decision as to what is subject to market exchange and what is not is largely a political one. Political power can prohibit or regulate the commodification of certain transactions for ethical and/or individual protection reasons (organ and/or blood donation, prostitution, surrogate motherhood, drugs, weapons). 23 Conversely, governments can decide to guarantee access to certain public services (health, education or housing) without monetary compensation (or only partial compensation) and on the basis of non-monetary and social criteria. It can also impose by law insurance schemes, such as the public pension scheme, totally or partially ousting the commercial sphere from this sector. For economic and financial reasons, public authorities can also decide whether or not to transfer the construction and use of certain infrastructures (roads vs. toll freeways) to the commercial sphere. Finally, the way in which natural resources, including land, are exploited is a major issue for every society. It can be a commodity with varying degrees of regulation, or it can retain the status of a common good and be managed by agreement between stakeholders on their respective rights and obligations.

Non-market activities are also substantial

In addition, non-market activities (without monetary remuneration) are numerous and important both socially and economically: domestic work (cooking, DIY, education), voluntary activities (charities, sports, leisure, etc.), tasks carried out without any real remuneration (out of a sense of service, duty, dignity, etc.). They represent a significant proportion of a country’s activity. According to an old but revealing OECD study, unpaid work is equivalent to a third of GDP. 24 in OECD member countries. A more recent study, limited to “care-work 25 shows that it represents 9% of global GDP. 26

The division between the market and non-market spheres varies over time and from country to country, depending on cultural and ideological developments, technologies and economic opportunities, and the outcome of social and political conflicts. 27 Companies also contribute to this variability. They may decide to produce certain goods in-house (see Essential 4.3) to save on transaction costs. 28 or, on the contrary, to outsource production in order to compete with external service providers.

Market mechanisms bring information and innovation and facilitate the matching of supply and demand

A market helps “supplier” companies (through knowledge of sales histories) to understand the “willingness to pay” of their customers and prospects, for which products and services, and to anticipate innovations. For consumers (citizens or companies), the market enables them to find out what offers will enable them to satisfy their needs or desires. In short, the market brings supply and demand closer together (if not on an equal footing).

Price is obviously a decisive piece of information for both buyer and seller: it’s information they necessarily know, unlike other information that may be deliberately hidden or simply not disclosed. They therefore necessarily pay special attention to it. From the point of view of economic theory, it is legitimate to give specific consideration to the role of this information in economic decision-making. However, an informed decision presupposes knowledge of the properties of the product purchased, including durability and potential impact on health and the environment. In addition, there are growing expectations regarding the traceability of product origins (which can increasingly be met by various digital processes). Legal provisions are needed to encourage companies to provide this information, and to enable legal action to be taken in the event of misinformation.

The stimulus of competition has a positive effect for the consumer – and more generally the purchaser – who can compare products and their value for money. They are not dependent on a single supplier or service provider. It’s also a source of innovation.

How (and who can) regulate market prices?

The decentralized information on millions of economic agents processed by markets cannot be known by an administrative authority whose capacity to set a price is limited. But competition is not a system that imposes itself and stabilizes spontaneously without the intervention of a regulator. In some cases, public authorities intervene directly to correct the undesirable effects of free pricing and competition, as in France for the price of all books, or in many countries for certain rents. And as may happen in the event of a crisis in basic necessities such as energy 29 or food.

Consumer power (the consom’acteur concept) is a decentralized power that is an important condition of “freedom of choice”. In principle, it enables the consumer to choose, within the limits of his or her means and relative prices, what seems most useful to him or her. By buying, the consumer can influence economic life. However, this power has its limits, and it would be naive to believe that it is sufficient to “govern” economic life. Companies influence consumer choices through advertising campaigns which can draw on advanced research in behavioral psychology and vast amounts of statistical data. 30 They have access to information that consumers do not have – and which has been multiplied considerably in the case of companies in the digital sector. They have access to political powers through trade associations and, for the larger ones, directly. This enables them to exert pressure on standards, regulations and taxation, all of which ultimately impact on consumer choice. Citizen checks and balances are therefore essential.

Entrepreneurial freedom is an essential political freedom

To be able to work for a decent wage, or to undertake freely (subject to compliance with social and environmental rules) and thus be able to “earn a living”, is a fundamental freedom. Depriving people of this freedom leads to economic dependence, which is politically dangerous if it becomes widespread. Conversely, ensuring that everyone can develop useful skills and live decently is a duty of justice for any society, and a guarantee of its lasting cohesion. Entrepreneurial freedom should therefore not be confused with the obligation to do so in order to live, or even survive. Collective bargaining and labor law are necessary to compensate for the de facto inequality between employees and the company, and not to leave the conditions of the employment contract to individual negotiation alone. Adam Smith himself was no fool of this asymmetry. In The Wealth of Nations, the founding book of the “invisible hand” myth 31 he wrote: “It is not difficult to foresee which of the two parties (masters or workers), in all ordinary circumstances, should have the advantage in the debate, and necessarily impose all its conditions on the other. The masters, being fewer in number, are able to consult each other more easily; and what’s more, the law authorizes them to consult each other, or at least does not forbid them to do so, whereas it forbids the workers. We have no acts of Parliament against leagues that tend to lower the price of labor; but we do have many that tend to raise it… It is said that we hardly hear of coalitions between masters, and every day there is talk of that of the workers. But you’d have to know neither the world nor the subject in question to imagine that masters rarely form coalitions among themselves. Masters are at all times and everywhere in a kind of tacit, but constant and uniform league, not to raise wages above the current rate. To violate this rule is everywhere an action of a false brother and a subject of reproach for a master among his neighbors and kindred spirits.”32

We’ll see inEssentiel 8 how the construction of the European market has been, and still is, highly regulated, with a very high level of intervention by European and national administrations working in close liaison with trade associations.

Find out more

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776

- Friedrich Hayek The Road to Serfdom (6th edition), PUF Quadrige, 2013

- Karl Polanyi The Great Transformation. Aux origines politiques et économiques de notre temps, Gallimard 1983

- Des marchés et des dieux, Stéphane Foucart, Grasset, 2018.

- Read Marion Cohen’s review of Stéphane Foucart’s book on the Chroniques de l’Anthropocène blog (Alain Grandjean’s blog) (18/10/2018)

- The reference book by Marcel Mauss, Essai sur le don, Flammarion, reprinted in 2021, originally published in 1925.

- Michael Sandel, What Money Can’t Buy, Seuil, 2014

Market equilibrium: an enduring myth despite the facts

The famous “law of supply and demand”: the reduction of markets to the quantity/price pairing

In this chapter, we focus on a particular vision of markets, the so-called “neoclassical” vision (see box), which emphasizes price and the role it plays in linking “supply” and “demand”. We’ll look at other approaches inEssentiel 5. But this dominant vision, taught in all economics courses, deserves a special focus. The basic idea is that, on a given market, the price of a product is formed by the confrontation of supply and demand. Quantities offered increase with price, those demanded decrease, and there are equilibrium prices equalizing supply and demand on all markets. At these prices, all sellers and buyers are satisfied, because they find a counterparty that suits them.

What is neoclassical economics? Synthetic presentation

The term “neoclassical theory” (or neoclassical school) was coined a posteriori to designate a current of economic thought born of the work carried out independently but almost simultaneously by William Stanley Jevons (1835-1882), Alfred Marshall (1842-1924), Carl Menger (1840-1921) and Léon Walras (1834-1910) in the early 1870s.

This current is largely dominant in contemporary thinking, and is based on several key concepts.

- The rationality of economic agents The rationality of economic agents: individuals are considered as “rational” actors who seek to maximize their satisfaction (called utility by economists), which is equated with consumption for individuals and profit for companies.

- The central role of markets as an institution for coordinating individual behavior towards an optimal situation: the economy is seen as a set of interconnected markets, which, thanks to price, naturally tend towards an equilibrium where supply equals demand.

- The role of prices: prices play a central role as signals for the efficient allocation of resources in the economy.

- Methodological individualism: analysis starts from individual behavior to explain global economic phenomena. It does not consider institutions as actors in their own right.

Finally, let’s mention the fact that the neoclassical school has been based on mathematics from the outset (utility is a function of a function of a function of a function of a function of a function of a function of a function of a function). utility is a function individual preferences are mathematical sets, an individual’s preferences are generally represented by a mathematical set called an indifference curve or surface, often convex, etc.). On this subject, see our mathematics in economics .

For Friedrich A. Hayek, what needs to be taught is that “prices generated by the just conduct of market participants – that is, competitive prices, free from fraud, monopoly or violence – were all that justice required”. 33

In this vision, producers would produce at the right price the right quantity of products, which would be bought at that price by consumers. There would be no unsold products or shortages. Markets would therefore balance spontaneously, in the sense that the decentralized confrontation of supply and demand would automatically lead to an equilibrium price. The vision of market equilibrium can be interpreted in two different and complementary ways from the perspective of neoclassical economists.

The first meaning is an empirical hypothesis. There is a mechanism that establishes the “equilibrium price” on markets. The second meaning is normative: when all transactions take place at the equilibrium price, transactions are Pareto optimal: it is impossible to improve the satisfaction of one agent without worsening that of another.

The neoclassical theory of price formation

Let’s start with transactions on one or a limited number of highly interconnected markets. 34 This is known as partial equilibrium. The price formation mechanism depends on the structure of the market or markets. For example, if the seller holds a monopoly and is faced with a crowd of buyers, he will be the sole master of the price, which he will set at the level that maximizes his profit (possibly by trial and error). If there are only a few sellers (oligopolies), the price will be set either by agreement (generally prohibited by competition law), or by mutual observation and successive adjustments (Cournot equilibrium). 35 ).

Neoclassical economists developed the ideal model of a perfectly competitive market by associating the following attributes with it:

- atomicity (no single seller or buyer has a market share that allows it to influence price);

- the market is defined by a homogeneous product whose qualities are as well known to buyers as to sellers;

- there are no restrictions on market entry or exit, which maintains competitive pressure;

- rational” actors (homo economicus) logically use available information to maximize their profits and utility function.

In the absence of dominant players, we need to add an equilibrium price formation mechanism at which “all” transactions are executed. Ideally, this mechanism presupposes “perfect, continuous and cost-free communication between all participants. Each potential buyer knows and chooses between the offers of all potential sellers”. 36 This crucial assumption, however, is not tenable in general: the formation of prices and the execution of all transactions must be organized. The economist Léon Walras who first mathematically represented the competitive “market”, was well aware of the difficulty, and introduced a “deus ex machina” for this purpose: the auctioneer who, by trial and error, identifies the price at which each seller finds a buyer, and vice versa.

The market would produce “optimal” prices: a certain vision of the social optimum

What about the normative evaluation of this partial equilibrium? The equilibrium price corresponds to a Pareto optimal situation in the following sense: at this price, all exchange gains are realizable and no further mutually advantageous exchanges are possible. By construction, this is not true at any other price level. If Walras’ auctioneer makes a mistake and announces a price higher (or lower) than the equilibrium price, sellers (or buyers) will not find a counterparty and some would be ready to lower (or raise) their price in order to carry out an exchange that would remain mutually advantageous without damage to the other participants.

Following Léon Walras, neo-classical economists also explored two questions: the possibility and uniqueness of a generalized equilibrium, i.e. one in which all markets are in competitive equilibrium as described above; and that of the “social” optimality of such an equilibrium. While continuing to leave aside the question of actual price formation, in 1954 Arrow and Debreu, along with McKenzie, identified the conditions necessary for such an equilibrium, in addition to those defining a competitive market. 37

One of these conditions is non-creasing returns to scale in production. 38 Competitive” prices agreed between “rational” consumers/producers with the same level of information reflect the relative productivity of inputs and the relative “utility” of outputs. The allocation of resources corresponding to the equilibrium is optimal according to Pareto: substituting the production and therefore consumption of one good for that of another would necessarily be to the detriment of the utility of at least one other consumer/producer. This is a definition of optimal resource use that is indifferent to the distribution of income prevailing at equilibrium, and is based on an individualistic conception of satisfaction. 39 We shall see later that many of the assumptions crucial to the achievement of a general equilibrium are not fulfilled in reality.

How markets work in reality: institutionalized mechanisms

Let’s return to the hypothesis of how markets work. It seems that “acts of exchange at the personal level create prices only if they take place in a system of price-creating markets, an institutional structure that is in no way generated by simple chance acts of exchange”. 40 Concrete markets, i.e. the organizations that regulate market transactions and enable their expansion, have in fact always been the product of political decisions that make them possible (local weekly markets, freedom to establish a business, to provide a service), that frame them (sanitary conditions, professional qualifications, various legal provisions…) and set norms and standards(see Essential 3). In some cases 41 public authorities delegate a legally-defined regulatory function to an agency. These decisions are often the result of a “partnership” or private/public cooperation, and may depend on highly specialized technologies (globalized financial markets, digital platforms, etc.).

Historians show that as early as the 13th century, the creation and regulation of weekly markets in France was a royal prerogative. 42 These markets brought producers and consumers together at fixed dates and places. The authorities provided additional services by securing the place against thieves and ensuring the accuracy of weights and measures. And, of course, they provided a source of tax revenue. In 1220, in a German-language work, we read: “A market can never be properly organized, if the naive can be deceived”. 43 The role that a regulating power must play in price formation had been recognized at least as far back as ancient Greece. Plato asks:

But within the city itself, how will citizens share the fruits of their labor with one another? For it is for this purpose that we have joined together and formed a state. Clearly, it will be by buying and selling. Hence the need for a market and a currency, a sign of the value of the objects exchanged.

Digital platforms and social networks create marketplaces

In part, networked digital platforms for the general public 44 such as Uber, Airbnb, Booking or Amazon, which have emerged over the past 20 years on the initiative of private entrepreneurs, follow the same logic as the royal or seigniorial powers that organized public markets. They exploit their own capacity for networking and communication to expand and even create new markets. Where necessary, they provide complementary services, such as securing transactions or delivering goods. As a result, they gain regulatory power on both sides – supply and demand – which they naturally use to maximize their private profits and oppose the emergence of organizations that would undermine their position of domination. The expansion of the markets they create can, however, have politically or socially damaging consequences on other markets (cab, real estate market, books and booksellers, labor relations), which may require a response from public authorities and new regulations. 45

In reality, market regulation – and hence the way markets operate and the prices they command – is never static. They may need to evolve in response to the emergence of new “business models”, changes in political orientation or new public policy objectives, such as the energy transition. This is why an essential question that always arises is “who makes the rules, for whom, with what objectives”. 46

Many price formation mechanisms co-exist in our society

The price-formation mechanisms themselves take a variety of forms, most rarely that of the auctioneer as assumed by Léon Walras. These mechanisms are the fruit of negotiations between the participants, who are generally unequal. This can legitimize public intervention to validate arrangements or correct biases in these mechanisms. The multiplicity of the latter reflects the heterogeneity of participants and products.

In addition to the online marketplaces already mentioned, here is a list of others:

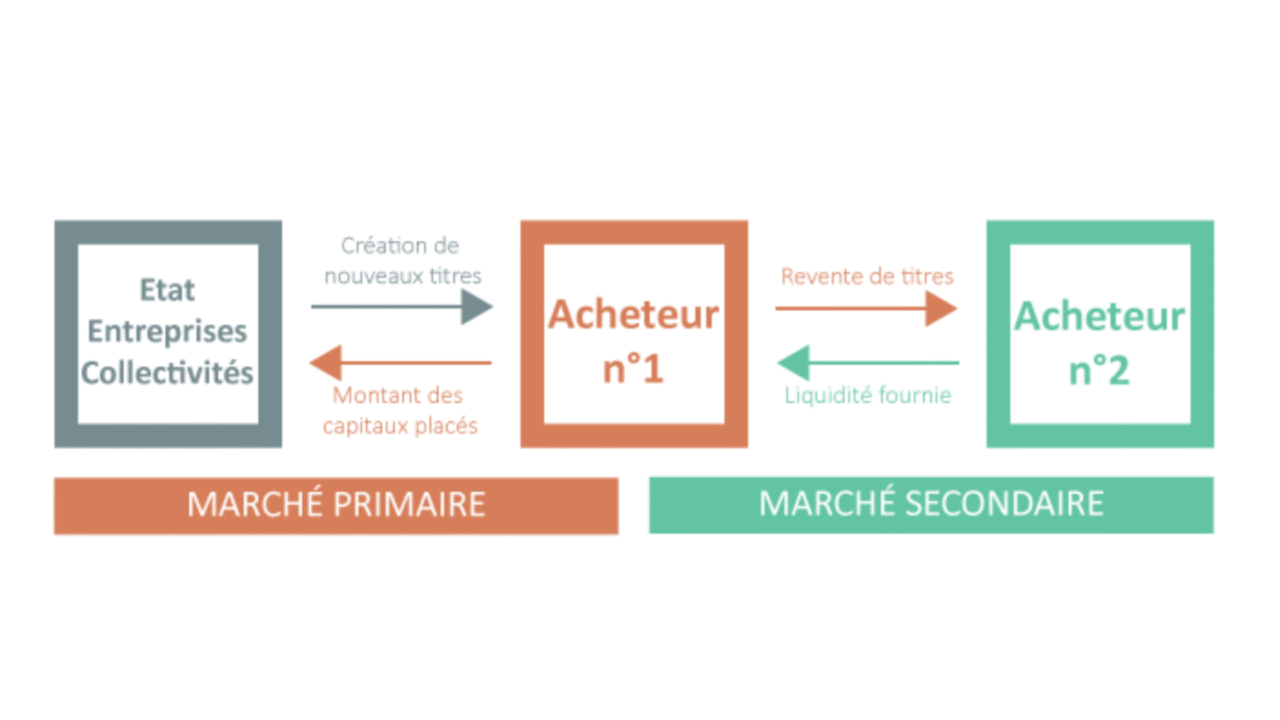

- Exchanges, which have become electronic, where buy and sell orders – sometimes generated by computer software – are executed instantaneously for standardized, dematerialized products (shares, bonds, promises to deliver raw materials, etc.); the wholesale electricity market and the ETS market forCO2 quotas. 47 market are also special examples.

- As a general rule, they set a non-negotiable price, leaving it up to the buyer to compare prices and the merchant to adjust the price according to sales. But there are also markets where negotiation is the order of the day.

- Small retailers themselves may be reduced to accepting prices imposed by wholesalers or producers, or conversely, like supermarket chains, may be able to negotiate their purchase prices.

- Auctions for fairly homogeneous products that “need” to be sold quickly (fish, crops).

- Auctions for works of art, real estate or stock liquidations, which are “unique” even if in competition with other similar goods.

- Bilateral contract negotiations.

- Collective bargaining (wages, prices of agricultural products between farmers, manufacturers and supermarkets).

- Invitations to tender.

In addition, public authorities intervene. On the one hand, by prohibiting sales at a loss, and on the other, by prohibiting cartels and establishing the rules of competition. Public authorities sometimes intervene directly in price formation. This may involve :

- Administrative decisions to set or limit prices; this is still the case in France for electricity tariffs, certain food products (EGALIM law) and some housing rents subject to the 1948 law. 48 … but there were many after the war, which saw a period of rationing. Similarly, following Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine, several countries introduced measures to moderate price rises for essential goods (energy, food), which had become unaffordable for part of the population and/or businesses.

- Prohibitions on certain transactions, such as the purchase of Russian gas in the wake of the war in Ukraine.

- Setting a minimum wage.

- Economic intervention by public authorities in a decentralized process (e.g.: book prices in France are governed by the Lang law, and no bookseller can offer a discount of more than 5% on a new book compared with the advertised price; this system has saved small bookshops from competition from the big chains).

- Since the post-war period, agriculture has been steered by interventions on prices and/or production quantities.

General equilibrium: from theory to the dominant normative ideal

However, by reducing market analysis to the price/quantity relationship and “disembedding” it from the institutional context, neoclassical economists pulled off an ideological masterstroke. This analysis links two meanings of the word “economy”: the optimal use of means to achieve an end, and the empirical social organization of production, exchange and consumption.

Recourse to the theory of competitive markets enables us to develop an overall vision of how the economy works, reflected in the existence of a general equilibrium that also satisfies certain optimality criteria. However, as we shall see inMisconception no. 2, the self-regulation of markets and the very existence of a general equilibrium depend on a number of crucial assumptions, the removal of which fundamentally calls into question the conclusions reached.

The market has nonetheless acquired a founding role 49 in explanations of how economies work, and its expansion became a “naturally” imposed, supposedly neutral objective, before becoming a political program. The market is then presented, from a normative point of view, as an ideal for the functioning of the economy ( as we saw in 2.1.1 ) rather than a tool for analysis and explanation.

The ideological and political philosophical basis of a “market economy” is the representation – very seductive at first sight – of a system that combines maximum individual freedom with efficiency (in the Pareto sense). For Milton Friedman, one of the most fervent apostles of neoliberalism, the market is THE democratic mechanism par excellence: “The political principle underlying the market mechanism is unanimity. In an ideal free market based on private property, no individual can force another, all cooperation is voluntary, and all who cooperate either benefit or do not need to cooperate”. 50

This approach leaves aside all political, social and ethical issues, and treats the question of income inequality independently of the economic process. If the market produces an undesirable distribution of income, redistribution through direct taxation and transfers can intervene, but care must be taken not to interfere with the price and wage mechanism. It is certainly recognized that the market needs a third institution to function: the state. But the state’s role is limited to securing ownership and the performance of contracts, and correcting market failures. 51 a point to which we’ll return later. For these economists, the state does not create the market: it must guarantee the minimum conditions for its operation and, where necessary, make the corrections required to bring the reality of transactions closer to the competitive ideal.

Bear and Bull, the two main market imbalances

In practice, a market is never in equilibrium, in the sense that all the desired supply would find a buyer, and vice versa.

A“seller’s” market is dominated by sellers: all products on offer find buyers, so it’s the sellers who are in a strong position. For a given price, demand exceeds supply: demand is therefore rationed, and sellers can raise prices, since demand will follow. Excess demand will diminish (until it is eliminated at equilibrium, if it occurs).

A “buyer’s” market is the opposite; it’s dominated by buyers because supply exceeds demand. Supply is therefore rationed by demand, and sellers have to lower their prices to try to (partially) sell it.

In the first case (“seller’s” market), prices are on an upward trend. At the extreme, we observe an “overheating” or even a bubble. In the second case (“buyer’s” market), prices are on a downward trend; in the extreme, we see a depression or even a recession or major economic crisis, as in 1929 or 2008.

Let’s take two examples. In the real estate sector, a buyer’s market situation can be identified by the fact that there are many properties for sale that are not finding buyers. Prices are on a downward trend. In concrete terms, an owner who wants to sell quickly has to wait or lower his asking price. In the seller’s market, the opposite is true: the buyer has to hurry to buy, there are few “products” available and prices are rising. The seller can wait, hoping to increase his selling price.

In the financial sector, the stock market is the ideal place to observe this type of imbalance. When prices rise because there is more buying than selling – a “seller’s market” situation – the stock market is “euphoric. A bubble can form. Conversely, when markets are anxious, buyers dominate, as sellers are unable to sell everything they want to sell. Prices fall and eventually crash.

These are known as bear and bull markets. A bear market is dominated by bearish behavior. A bull market is bullish.

General equilibrium theory: an illusion far removed from the facts

However, market theory did not stop with the abstract identification of a “competitive general equilibrium”. Later contributions lifted some of the assumptions made in the initial mathematical theory, and studied the consequences. In Essentiel 3, we will return to the subject of market regulation, some market “failures” and possible solutions. Let’s limit ourselves here to describing four phenomena that call into question the existence of a general equilibrium in structurally stable markets.

Effective and notional supply and demand

The first is based on the distinction between “effective” demand (or supply) and “notional” demand. In the absence of the Walrasian auctioneer, a “seller” may not find a buyer. His notional offer (that which he was prepared to satisfy if an equivalent demand was expressed) does not materialize, and he is left with a stock of unsold goods which forces his effective demand to fall short of his notional demand, i.e. that corresponding to a situation in which he would have carried out the planned sale. A typical example is a situation where the unemployed spend less than they would if they were in work, which discourages companies from producing more.

We’ll come back to this major point in more detail inEssential 5. The idea of the possibility of a general equilibrium resulting solely from the interplay of supply and demand is based on Say’s law, known as the law of outlets. According to this law, also known as the law of outlets, supply creates its own demand, since production generates purchasing power equivalent to that production, which will therefore find a buyer. It’s true that the cost of production for a company is equal to the income (from employees, suppliers, subcontractors, bankers, etc.) it distributes. But for the company to finance these expenses, it must sell all its production. So it’s sales that generate purchasing power, not production itself. J.B. Say’s reasoning is circular and implicitly based on the conclusion he wants to draw. The crisis of 1929 demonstrated this error in a spectacular and, unfortunately, violent way for its victims.

Speculative phenomena

The second is based on a price formation mechanism that sustains speculative bubbles (see box). This is the case when market participants act not according to economic rationality, but on the basis of what they think will be the behavior of other participants. This type of phenomenon is most common in financial asset markets. Financial regulation is needed to control the negative consequences (seeMisconception #4: Financial markets are efficient). But other assets such as real estate, or even tulip bulbs as in 1636-1637 52 can also be the object of speculative movements.

What is a speculative bubble?

A speculative bubble is a situation in which the price of an asset, such as shares, real estate or commodities, rises excessively. At some point, the players, usually suddenly and as sheepishly as they were buyers, start selling the assets in question, causing the bubble to burst: prices fall rapidly. This is the famous case of the tulip crisis. In 1635, 100,000 florins 53 to buy a batch of 40 bulbs. A week after the bubble burst, in 1637, tulips were worth less than one hundredth of their previous value.

This was also the case with the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, when tech stocks saw their prices rise exaggeratedly before bursting in 2000. And, of course, there was the sub-prime bubble. 54 of the 2000s, which led to the global financial crisis of 2007-2008.

What’s special about a speculative bubble is that it only becomes clearly identifiable as such once it has burst. On the one hand, the bursting of a bubble is unpredictable, and on the other, situations of strong asset price rises do not always lead to one.

A bubble is often considered to occur when a large number of investors buy assets in the hope that their prices will continue to rise, regardless of the underlying economic factors that would justify such an increase. But this explanation is based on the idea that there is a fundamental value for a given asset (usually calculated as the discounted sum of future annual returns). This idea is hard to sustain: how can we believe that the value of Tesla shares is justified by the company’s economic prospects? Its market capitalization in February 2025 is $1,000 billion, a “multiple” of 160 times its earnings. Even the “multiples” of the most highly-valued tech giants (Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Google, Meta) are much lower, between 20 and 50 (although still very high).

Asset prices are therefore the result of more or less rational buying and selling behavior, which takes more or less account of the economic performance of the underlying companies or assets. They are also subject to political or other systemic effects. Speculative bubbles are therefore as difficult to detect as they are to avoid.

Natural monopolies

So-called “natural” monopolies include networks (rail, road, electricity, water, etc.). For the network operator, the marginal monetary cost of an additional user is zero or very low (a little more maintenance). But fixed costs justify setting a price well above marginal cost. As the operator is in a monopoly situation, this price must be regulated when the network is not public.

For the example of electricity, see our fact sheet on opening up the electricity sector to competition.

The example of increasing returns: the gap between theory and reality

The original hypothesis of non-creasing returns to scale

The notion of diminishing returns is intuitively understandable: there would be a point beyond which increasing the number of hours of labor (one of another production factor), with a constant number of machines, does not proportionally increase output. The cost of the last unit produced is higher than that of the previous units. Or, to put it another way, the profitability of this last unit is lower than that of the previous ones. David Ricardo made diminishing returns an economic law by observing the case of agriculture. At the time, farmland was cultivated in descending order of yield: “good” land first, bad land last. Today, this is the case for mining deposits for energy or mineral resources, but as we shall see, it’s far from being a general rule.

This central assumption of increasing costs of the last unit produced (and therefore decreasing returns) is essential in establishing the theory of general equilibrium. Firms are thus limited in their production: there comes a time when it is not in their interest to produce more. If demand for a product increases, they can raise the price – up to a certain limit – which sets the price. Conversely, if demand falls, they can cut production without loss (since they are reducing marginally less profitable production).

Conversely, if – and as long as – the cost of the last unit produced remains equal to or lower than the previous one, it is in the company’s interest to increase sales and production. This means that the biggest companies, or those with the financial strength to grow faster, can wage a price war while covering their fixed costs. This war gradually ruins smaller companies. Concentration ensues, and the market is eventually dominated by an oligopoly or monopoly, capable of controlling prices, which is the opposite of the perfect competitive equilibrium resulting from general equilibrium theory.

The gap between theory and reality

In practice, increasing returns to scale can be observed in many sectors. This can lead to the formation of monopolies, high concentrations and oligopolies.

In IT, and particularly in the software industry, returns are increasing. 55 These are fixed-cost industries, with zero marginal cost: the last copy of software costs nothing. The main cost is that of setting up the team, running it and developing the software, all of which are fixed costs. In this case, the company does not sell according to the cost price of the unit sold (with a possible margin), but always has an interest in selling as many products as possible, while avoiding a price collapse.

Many industries have high fixed costs and low marginal costs. Just think of the publishing or audiovisual industries. In the energy sector, highly capital-intensive energies such as nuclear or solar power have very low or zero marginal costs (for more details, see our fact sheet on the electricity market and the one on the cost of financing renewable energies).

Increasing returns can also be seen in the automotive sector, where the top ten of the world’s fifty automakers account for 70% of total production. 56 The banking sector, which has become considerably concentrated, is subject to increasing returns, mainly due to money creation mechanisms. The larger a bank’s network, the fewer “leakages” it has to contend with, and the more money it can therefore create and earn on its lending activities. But size also plays a part in absorbing fixed costs linked to legal, advertising and marketing and structural costs.

In more traditional industries, fixed costs are generally high, and it is not at all obvious that the marginal costs of products sold are decreasing. Manufacturers are all looking for technical advances that will enable the opposite to happen. In many sectors, production costs fall as cumulative output rises (this is the notion of the experience curve, see box).

The notion of the experience curve

This concept was discovered in the USA in the late 1960s by Bruce Henderson. Sales of microprocessors were growing explosively, and their price had been divided by ten between 1964 and 1968. Henderson formulated a simple rule: prices would fall by 25% every time the cumulative output of an industry (dubbed “experience”) doubled. Fifty years later, this rule explains why, as the industry’s experience has been multiplied, in order of magnitude, by 1 billion, microprocessor prices have been divided by 1 million. And that’s why everyone has in their pocket, with their smartphone, a product that would have been worth 200 million dollars fifty years ago!

Source : See La leçon de l’expérience, post by Xavier Fontanet, former CEO of Essilor, on Les Echos (08/02/2018).

Such oligopoly-controlled sectors pose a dilemma for competition policy. Concentration is unfavorable to consumers, as it enables companies to set high prices that are not, or only slightly, mitigated by competition. It also makes it easier for the few dominant companies to influence regulation (see Essentiel 3 and our module on Enterprise). On the other hand, imposing a reduction in company size to increase competitive pressure can prevent “economies of scale” from being achieved. Some observers believe that Europe’s overly rigorous competition policy (see Essentiel 8) has prevented the emergence of “European champions”, particularly in the highly innovative digital sectors. Another cause, however, could be the fragmentation of European research budgets compared to the US federal budget. In fact, competition policy has not prevented the consolidation of major European groups with global reach in the automotive, chemicals or banking sectors, nor, when a few states have been willing to cooperate, has it prevented the emergence of Airbus, the only aerospace group capable of competing with Boeing.

In conclusion, these examples show that increasing returns are the norm rather than the exception. So why have neoclassical economists focused on diminishing returns? For two reasons. Firstly, historical: it’s true that land was farmed in order of diminishing returns. As agriculture was dominant in the 18th century, the hypothesis was unreservedly extended to other sectors. Machinism had yet to prove its worth. The other reason is less noble: the demonstration of the general equilibrium theorem is based on the hypothesis of diminishing returns… To highlight this simple fact too clearly is to risk knocking this fine theoretical edifice off its pedestal.

The work of the neoclassical school on market imperfections

Economists were quick to note, however, that returns can be increasing. Keynesian and Marxist economist Joan Robinson, for example, observed that companies seek to build monopolies that enable them to set prices and make higher profits. This is what economist Edward Chamberlin would later call “monopolistic competition”. In 1977, economists Avinash Dixit and Joseph Stiglitz developed a model of monopolistic competition 57 (which shows how increasing returns to scale interact with product diversity in imperfectly competitive markets).

These questions are at the heart of the industrial economics school, of which Jean Tirole (“Nobel Prize” in economics 58 in 2014) is one of its pillars. 59 This school provides new tools and concepts for analyzing market structures (monopoly, oligopoly, monopolistic competition), firms’ strategic behaviors (pricing, innovation, barriers to entry, differentiation) and the effects of these behaviors on economic efficiency and consumer welfare.

It deduces the regulations needed in a world where imperfect markets are the norm, to avoid abuses of dominant positions while generating incentives for innovation and investment. These studies suggest tariff mechanisms for network industries and for regulating digital platforms. Nevertheless, in seeking to “correct market imperfections”, these studies remain within the same intellectual framework: that of the market as the central reference point towards which the real economy must “converge”. They do not allow us to envisage, or even think about, other types of coordination mechanisms.

Find out more

- Michel Devoluy L’économie : une science “impossible” – Déconstruire pour avancer, Vérone Éditions, 2019

- Benjamin Coriat, The common good, the climate and the market. Réponse à Jean Tirole, Les Liens qui Libèrent, 2021

- Jean Tirole, Theory of Industrial Organization, Economica, 2015

- Jean Tirole, Économie du bien commun, PUF, 2018

- Michel Volle, iconomie, Xerfi and Economica 2014

- See also Increasing returns on the blog of the author, Michel Volle

Operating and regulating competitive markets

In 2008, speaking before the US Senate on the causes of the financial crisis, Alan Greenspan, who had been a fervent defender of free markets and Chairman of the Federal Reserve (the US central bank) until 2006, admitted that he had been mistaken about the supposed self-regulating capacities of financial markets. A few months earlier, Sir Nicholas Stern had declared climate change to be the greatest market failure of all time. In March 2021, the Servier laboratory was convicted in the first instance for having marketed Mediator, a drug proven to be dangerous and responsible for several hundred deaths. But the French National Agency for Drug Safety was also condemned for failing to suspend the drug’s marketing authorization quickly enough. In 1976, the Seveso industrial disaster 60 in Italy caused 30 direct deaths and an ecological disaster. Dieselgate”, the fraudulent use of techniques to reduce the quantities of pollutants emitted by Volkswagen Group cars, put an end to widespread practices in the automotive industry that were seriously damaging human health and the climate.

These examples demonstrate the importance of regulations in the pursuit of the general interest, and the need to have the capacity to enforce them. In reality, there is no reason to believe that “markets” – that is, private enterprises motivated by profit maximization– left to their own devices, serve the general interest. In this Essential, we will first review the various market “failures” that require correction, and the various instruments available to correct them.

The current public policy approach of seeking to “correct” market failures is indicative of a “market economy” framework of thought, in which economic policy is designed to reduce the gap between the ideal of competitive markets and reality.

Making markets work

Before looking at the failings of the “markets”, let’s recall the rules that are essential to their operation in practice, and stress that there’s nothing “natural” about these rules.

Property rights are the basis of markets

The first rule is that there is no market unless property rights are clearly established, and their holders are confident of being able to enforce them. What is commonly referred to as a “market” economy is in reality an economy of private or public “property rights” defined in such a way that they are transferable. The definition of rights is far from trivial, and varies according to the object: land ownership, intellectual property (copyrights, patents), ownership through financial assets (shares). Their protection can be more or less solid, more or less difficult to enforce, more or less dependent on judicial assessment. The exact definition of property rights 61 is always political, and therefore liable to change, in particular to take advantage of new economic and profit opportunities. Political decisions guide both the speed of economic restructuring and its social consequences. Historical examples abound. One of the most famous, considered by Karl Marx to be decisive for the expansion of capitalism, is the enclosure movement, the transformation in the UK of communal property, or property open to common use, into large hedged plots for the exclusive benefit of sheep farming. Begun in the 13th century, it culminated in the adoption, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, of legislation virtually ending communal property and allowing its transformation into large private estates. 62 A current example is Total’s appropriation of land belonging to the Tanzanian state but traditionally used by peasants. 63 Intellectual property, i.e. the privatization of the use of knowledge – by its very nature a common good that does not wear out when it is used – is a major political issue with immense distributive consequences. 64 (see alsopreconceived notion n°11Thecommodification of knowledge through highly protective patents guarantees a rapid pace of innovation). At the heart of the digital industry, questions of data security and personal data ownership are major issues that divide the world, with Europe being more protective, with the RGPD law and the Digital Services Act. As for “artificial intelligence”, its use raises numerous intellectual property issues (notably for training AI systems) that we won’t go into here.

No courts, no markets

The second condition for the functioning of an open market economy is trust in the respect and fulfillment of contractual commitments. In general, state justice is in charge. Sometimes, however, the contracting parties agree in the contract itself to have recourse to private arbitration tribunals, particularly for international trade contracts. 65 In return for protecting the contracting parties, the law provides a framework for contractual freedom.

In the eyes of the law, not all contracts are authorized and “respectable”, either because of the personality of the contracting parties (abuse of weakness, minority), or because of the purpose of the transaction (prostitution, surrogate motherhood, drugs), or because of “abusive” clauses.

Shakespeare’s play Merchant of Venice brings to a climax the dilemma of public power in a situation where enforcing a contract – a necessity to protect the economic order – would have consequences contrary to the supreme order of the city, which is to protect the lives of its citizens. A similar problem is currently posed by the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). This Treaty, which aims to protect private international investment in energy against expropriation or changes in legislation affecting profits, is now proving extremely costly for states wishing to implement a disengagement from fossil fuels to combat global warming. Let’s not forget that in Shakespeare’s play, the protection of the physical integrity of citizens ends up taking precedence over the respect of the contract through a threat leading the creditor to renounce of his own accord. He may well get his due, but he will be prosecuted for the incidental consequences.

Find out more

To better understand the institutions that make the market work, we have divided them into four categories: – those that create the market – those that regulate it – those that stabilize it – those that legitimize it

Structuring markets: combating concentration

Attention must be focused on the inequalities between players. This is what competition policies are all about, and we’ll look at some European examples inEssentiel 8. Let’s take an American example. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first piece of modern competition law to outlaw certain anti-competitive practices:

- Cartels (agreements between companies aimed at restricting competition, such as price fixing or market sharing);

- Monopolies: the law also prohibits the creation or domination of markets by a single company in such a way as to eliminate competition. If a company uses a dominant position to exclude competitors or distort competition, it is breaking the law.

- Unfair commercial practices, such as the use of coercive means to exclude competitors, or the exploitation of partnerships and commercial agreements in such a way as to harm competition.

The literature on this subject is extremely rich, and we’ll confine ourselves here to a few examples.

Many economic sectors are dominated by a few companies

The digital sector is the first to come to mind, whether in hardware or software. 66 (Apple, Microsoft, Google, Acer, Nvidia, Samsung, Huawei…) or platforms (Facebook, Amazon, Uber… and their Chinese equivalents (Alibaba, Temu…). What’s more, many traditional industrial and service sectors are dominated worldwide by a very small number of companies. We have already seen a few examples above. Let’s complete the picture. Four companies – Maersk (USA), MSC (Italy), CMA CGM (France) and Cosco shipping (China) – account for half the world’s maritime trade. The agricultural sector 67 is characterized by a large number of farms, surrounded upstream and downstream by some of the world’s most powerful companies. Four companies, John Deere (USA), CNH industrial (Netherlands), Kubota (Japan) and AGCO (USA) capture 53% of the agricultural machinery market. Four companies, Bayer-Monsanto (Germany), Syngenta-ChemChina (China), Dupont-Dow (USA), BASF (Germany), capture 84% of the crop protection products market. Downstream from farmers, 90% of the trade in agricultural products is carried out by four companies: Cargill (USA), Louis Dreyfus (France), Archer Daniels Midland (USA), Bunge (USA). Added to this is concentration in the production and distribution of apparently distinct brands of beverages 68 such as beer. The pharmaceutical industry is also highly concentrated. The top five groups worldwide (Johnson & Johnson, Roche, Pfizer, Bayer and Novartis) account for around a quarter of the market. 69 (This list of highly concentrated sectors is by no means exhaustive).

In the “Business in the Anthropocene Era” module, we discuss the harmful consequences of such concentration (and the resulting corporate gigantism).

The main drivers of economic concentration

In addition to the economic rationale of increasing returns, these concentrations have been favored by three main factors: the liberalization of world trade, and the fall in unit transport costs, in particular due to the gigantism of cargo ships, 70 and the geographical and long-term extension of intellectual property protection. 71 Mergers enable production chains to be fragmented geographically 72 by pursuing strategies of vertical integration, from access to raw materials to marketing, and thus achieve economies of scale. They also make it possible to dilute legal risks (notably social and environmental) that do not accrue to the parent company.

Negative consequences for society as a whole

Such concentrations pose a number of problems. The first, quite classic, is the direct and immediate impact on buyers: prices that are too high in relation to costs, and a weakening of quality. The second problem arises from the ability to influence legislators and supervisory agencies, 73 including through blackmail. The third, particularly visible in the agricultural sector, is the ability to shape production patterns throughout the sector. The economic dependence of many farmers has become such that it has become extremely difficult for them to move away from the intensive agricultural model. Agroecology, despite its ability to feed the world while respecting the planet, clashes head-on with the interests of those companies that have shaped the current model, and made it adopted by the majority of agricultural players, consumers and public authorities. In the pharmaceuticals sector, the geographical fragmentation of production chains contributes to restricting supply, resulting in shortages of basic medicines. In the energy sector, the absence of competition and the ability to influence political decisions enable dominant companies to manage the speed of substitution of fossil energies by renewable energies at a rate that maximizes their financial profitability, but which remains too slow. 74 from the point of view of climate change.

Faced with such mergers, competition authorities are not in a position of strength. They cannot pursue the illusory goal of atomistic competition. When European competition authorities are called upon to judge mergers, they weigh up the potential benefits of economies of scale and the securing of production chains, particularly in the case of vertical mergers, against the weakening of competitive pressure. They must ensure that the market remains “contestable”. 75 They must ensure that the market remains “contestable”, i.e. that established companies are unable to erect barriers to entry. 76

Correcting the main market failures

A first category of “failures 77 that need to be corrected are the so-called externalities externalities , i.e. the actual or potential impact of activities on populations, third-party activities or the environment. Examples include emissions of pollutants (liquid, solid or gaseous), greenhouse gases, noise pollution and the risk of industrial disasters.

A second category of deficiencies relates to theinformation required for an “informed”transaction . Consumers need to be assured that what they consume will not harm them. They may also wish to know whether the goods they buy are produced in conditions that respect workers and the environment. The multiplicity, diversity and complexity of goods consumed preclude an individual assessment, which would be ineffective because information is a common good.

Thirdly, public authorities must regulate “natural monopolies”, in particular infrastructure networks for transport, energy or the exploitation of natural resources (mines, water, etc.). They can do this either by making them public property, or by setting conditions for their exploitation.

The jalopy market or adverse selection

Asymmetrical information between a seller who can differentiate whether a product is of good quality and a buyer who cannot, is also a major cause of market failure. The metaphor of the “jalopy” market for used cars presented by George Akerlof in his 1970 article Market for Lemons illustrates this point. In a simplified version, the buyer is not prepared to pay more than he values the bad product, and the seller is not prepared to sell the good product at the price of the bad one. The buyer’s preference, however, is for the good product, even if paid at the price that would be demanded by the seller. Uncertainty over quality means that either the transaction does not take place, or the buyer buys the bad product at the lower price demanded by the seller (who would also have preferred to sell the better product). The solution is suboptimal from both points of view. The remedy may lie in a credible guarantee given by the seller, possibly combined with a certificate of passing a state-administered or regulated roadworthiness test.

Market short-termism: the “tragedy of horizons

Fourthly, markets are short-sighted, leading to the tragedy of horizons, to borrow a phrase from Mark Carney, then Chairman of the Financial Stability Facility and Governor of the Bank of England, who in 2015 used and popularized this remarkable formula, in relation to climate change. 78 It is clear that, in this field, the “law of the market” does not allow us to take into consideration economic effects (positive or negative) that are revealed over the long term. Markets are short-termist for a simple mathematical reason. The calculations of economic players, and financial players in particular, are made by “discounting” present and future income and expenditure. For listed companies, the discount rate is necessarily close to the rate with which they finance themselves, i.e., the rate weighting the “cost” of equity and debt. To take an example, if the return expected by shareholders on equity is 15%, if debt is raised at a rate of 3% and if it represents 60% of financing, the weighted rate is 7.8%. 79

The usual practice in France for large companies is to use a rate of between 8% and 12%. A rate of 10% leads to a doubling of values every 7 years, i.e. a multiplication by 16 in 28 years. In other words, the horizons considered with this type of calculation are very short (since, conversely, an expense or income appearing in 28 years is worth one-sixteenth of what it would be today!) Another way of expressing the same thing is to note that the investments made by these companies must, according to the financial departments, be recouped in order of magnitude over 3 years.

This “short-termism” is clearly a “market failure”. It applies not just to climate change, but to the whole issue of sustainable development. The market is intrinsically too short-termist to consider long-term issues on its own. Certainly, some shareholders have long horizons, at least for part of their assets, and seek long-term capital gains rather than immediate returns.

But that’s not the majority of them. To reintegrate the long term into the choices made by companies and financiers, we need resolute action from the public authorities.

Finally, there is no reason to believe that “market” mechanisms lead to a socially and politically acceptable distribution of income. The same applies to access to certain essential goods and services, such as health insurance or opening a bank account.

In the following Essentials, we’ll look in more detail at the regulation of two very specific types of transaction that neoclassical theory equates with a “market”: “financial” products and “natural resources”.

Investment, incentives, regulation, pricing: how government can correct market failures

We will confine ourselves here to identifying the various public policy instruments that can be used to steer markets. They fall into three broad categories: public investment, financial incentives (taxation and pricing, transfers and subsidies, credit policies), and the use of public funds. 80 and regulation. Regulatory instruments include transparency and nature protection obligations, prohibitions on collusion or discrimination, mandates (obligations to provide certain services), prudential obligations (insurance, equity capital), labor law, including employee consultation and participation in company decisions (joint decision-making or otherwise), pollution and safety standards – which can take the form of either result-based obligations (maximum emissions of pollutants) or means-based prescriptions (anti-explosion or fire-fighting measures).

In general, policies need to combine several instruments. One reason for this is the need to take account of the impact of measures on all the objectives pursued, particularly on income distribution. Another is that several markets may be “failing”. At first glance, the idea of combating global warming by heavily taxing all greenhouse gas emissions, irrespective of their origin, seems seductive. Those who advocate such an approach suggest redistributing tax revenues to compensate for the loss of purchasing power of the most vulnerable. But there is also the problem of access to credit and the interest for an investor, even an affluent one, of a heavy investment in thermal renovation whose return is only guaranteed in the very long term, and who does not have all the information enabling him to judge the necessity of the means and the quality of the results. This investor, thinking in the shorter term, would see his short-term liquid capital or debt capacity cut back, with no immediate return and no certainty that technological innovations would not render his investment obsolete sooner than expected. This market failure can be corrected by combining a legal obligation to act with subsidies and certification of resources and results by accredited bodies.

The economy can’t be reduced to a market-state pairing

In previous Essentials, we analyzed economic processes in binary terms: on the one hand, markets; on the other, the state – securing transactions and regulating them. We shall see that this binary vision, dominant among many economists, impoverishes the analysis of economic relations and the debate on public policy. It can easily lead to errors of diagnosis and prescription. Here, we describe other ways of contributing to the coordination of economic activities. These modes of coordination complement or replace the state and/or the market, and interact with them. They often fly under the radar, but are nonetheless essential to understanding how the economy works.

The importance of relational networks, particularly in the job market

Wage formation and labor relations are largely shaped by various institutions and regulations, the legacy of decades of political and social struggle. These institutions include labor law, ancillary social rights (retirement, health insurance, unemployment insurance), the right to strike, the right of association and representation by professional organizations, and social dialogue. 81 These formal institutions are complemented by relational networks.

As we saw at the end of the first Essential, Adam Smith poked fun at those who believed that “the equilibrium wage” was linked to the invisible hand 31 of a competitive market. He pointed to the existence of tacit coalitions between bosses which, with the complicity of the authorities, kept wages down. This was made all the easier by the fact that employee coalitions were forbidden and repressed.

The mechanism that holds the coalition together is reputational, i.e. the risk of being excluded from a social network that favors transactions between “trustworthy” people. There’s no doubt that the members of this entrepreneurial “elite” used their collective power for more than just keeping wages down. We can assume that within this coalition, information circulated on the personalities of the workers, on the trust that could be placed in a particular “foreign” merchant, or even on the financial situation of a particular coalition member, and on the best way to organize, and then use, political power to protect “one’s” property rights and rents. 83

At the other end of the social scale from Smith’s coalition, immigrant networks in host countries (diaspora) illustrate some of the mechanisms that emerge when formal institutions or the market fail. The main reason for the emergence of such networks is the replication, in the host country, of solidarity or mutual recognition existing in the country of origin. For their members, these networks are a source of economic and social support, insofar as they facilitate transactions between them, thanks to mutual trust or “spontaneous” solidarity rooted in belonging to the same community. They are also a source of information for new arrivals on the opportunities offered by the host country, particularly in terms of informal employment, even if illegal. 84 Conversely, an employee’s membership of a diaspora can be a source of information for a potential employer, and at the same time constitute an implicit guarantee on the part of the diaspora that the promised service will be provided. Similarly, networks of alumni of recognized professional schools, sometimes organized into formal associations, circulate information and can guarantee certain “qualities”, as can networks based on communities of belief.

However, networks and associations are no more of a panacea than markets. Like markets, they can have major negative external effects requiring state intervention. They can develop parallel economies and clientelism that exclude non-members rather than strengthen the community’s ties with third parties. They may also develop clan and patriarchal structures. Just think of organized crime, whose methods of disciplining members are generally coercive and punitive to the extreme. 85

Networks, professional associations and civil society representation

The emergence of reputational networks or the formation of associations can also be a means of securing transactions between companies. In general, it is all the more likely and necessary when the state is weak (and access to justice is costly, unreliable or inequitable). The state may also consider that the investment it would require to regulate a very specific market is disproportionate to the general interest, or that the “market” can be too easily relocated and placed beyond the reach of jurisdiction for it to regulate effectively. In such cases, members of informal networks may be encouraged to form formal associations and set their own rules and procedures for arbitrating disputes. This is the case, for example, of the New York Diamond Dealers Club. Membership of this association is also a signal to third parties that certain standards have been met, and that arbitration is possible. In this case, the “Club” takes the place of the legal legal system both for relations between its members and in its relations with third parties. The “Club” also has a representation function vis-à-vis public authorities when general interests are at stake.