This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

One of the most recurrent economic debates is between those who, to stimulate economic growth, recommend boosting the supply of production by companies and those who prefer to act on consumer demand.

According to the proponents of supply-side economic policies 1 public intervention must be kept to a minimum if the economy is to function properly. The aim is to reduce the constraints “weighing” on companies (taxes, social security contributions, regulations, labor market framework). With this in mind, a great deal of attention is paid to controlling public spending and the public deficit, to avoid the risk of increasing the tax burden. The role of the state is limited to ensuring social peace and the smooth functioning of markets. It may also play a role in correcting positive externalities (via incentives for private innovation, for example) and negative ones (by taxing harmful behavior).

For demand-side policy advocates, this means focusing on consumer demand, since companies invest and hire according to their actual or anticipated order books. The main levers are therefore to mobilize public budgets (public investment and procurement, high-quality public services), raise earned incomes, lower taxes on consumption and increase the incomes of middle-class households.

While this presentation is obviously schematic 2 the fact remains that these theories have played a dominant role in economic debate and on the political agenda, with demand-side policies dominating during the 30 glorious years, and supply-side policies dominating since the 1980s. In this fact sheet, we look at the different levers of supply-side policies, their theoretical justifications and their actual effectiveness. 3 .

Supply-side policies are supported by various theoretical arguments

Milton Friedman, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, has long defended the idea that the economy would be better off if taxation were reduced, markets deregulated and public spending cut. His work is based in particular on the ideas of Arthur Laffer and Jean-Baptiste Say, which we will discuss below. From the 1970s onwards, this school of thought largely influenced the implementation of supply-side policies by neoliberal governments: Helmut Schmidt in Germany, Ronald Reagan in the United States, Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, before winning over the Social Democrats (Schroeder in Germany, François Hollande in France). Here, we take a closer look at some of the arguments put forward.

The law of markets: supply creates its own demand

The mechanism of supply-side policy is seemingly straightforward: a reduction in business costs lowers the final price of goods and services, thus increasing consumer demand, and in turn leads to greater production, hiring and investment, which in turn increases household incomes, and so on. This line of reasoning holds true if we assume the “law of outlets “, enunciated by Jean-Baptiste Say over two centuries ago. In a nutshell, this law stipulates that any product supply creates its own demand: the goods (investment or consumer) and services produced are necessarily sold, because the purchasing power generated by their production makes it possible to buy them. Growth therefore depends solely on production. Taken up by neoclassical economists at the end of the 19th century, this concept, which assumes an automatic equilibrium between supply and demand, is still largely dominant today, and structures the construction of macroeconomic models.

There are several arguments to show that Say’s Law is wrong. The most obvious is that what is produced is not necessarily sold. It is not production that pays employees, but the sale of that production. Producing more only translates into purchasing power if this surplus can be sold. To ensure that this is the case, consumers must want to consume more, and have the means to do so, which is not guaranteed. Furthermore, this “law” overlooks the role of credit and ignores the effects of money, which is not just a “veil over exchanges” as Say claimed.

International competition

In a world of fierce international competition, supply-side policies aimed at reducing the burden of taxation are supposed to support companies’ competitiveness, i.e., their ability to win export market share. Indeed, lower taxes would enable them to charge lower prices, and thus differentiate themselves from their international rivals.

A company’s international competitiveness is primarily influenced by the tax system of the country in which it produces its goods. In an attempt to gauge the impact of this tax system, the think-tank Tax Foundation has developed the International Tax Competitiveness Index. This indicator is intended to reflect both the competitiveness of the tax system 4 and its neutrality 5 . In the 2021 edition, France was ranked 35th out of 37. It is undeniable that France has a heavier tax system than other countries. That said, we would need to reduce compulsory levies by 13 points of GDP to reach the top of the ranking. This is neither desirable nor feasible without imploding our social protection system.

In addition, the World Economic Forum regularly publishes the Global Competitiveness Report, which covers 140 countries. The competitiveness indicator used is based on various parameters, not all of which are linked to supply-side policies. Among the factors that lower France’s ranking are red tape and labor relations. Tax pressure is therefore not the only criterion for companies and entrepreneurs. The quality of life, the healthcare system, the quality of training in the various trades, the legal framework in which to do business, the quality of infrastructure and the industrial fabric already in place are all parameters that come into play when choosing a location. However, to be competitive on these criteria requires public funding, which means raising taxes.

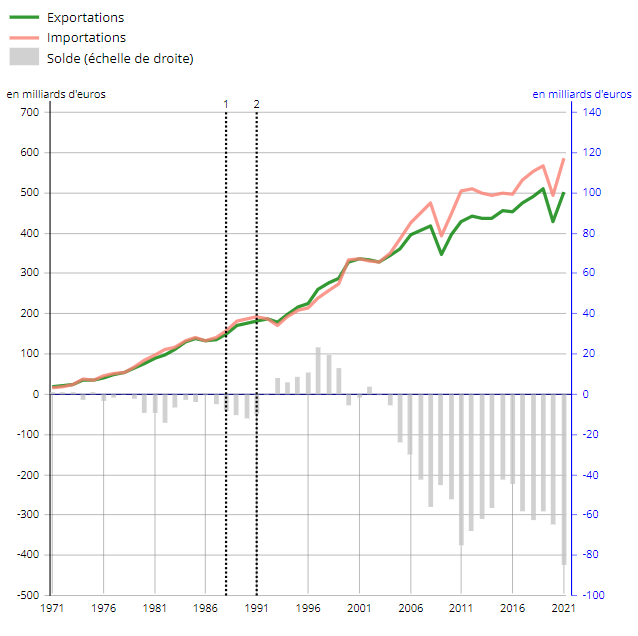

It should also be noted that the economy of a country like France relies not only on external demand, but also on domestic demand. Calibrating a policy for exporters alone leaves out an entire sector of the economy. In 2021, exports will account for 29.4% of French GDP, while imports will represent 31.4%. This is obviously significant, but domestic demand is still the main driver of GDP and jobs.

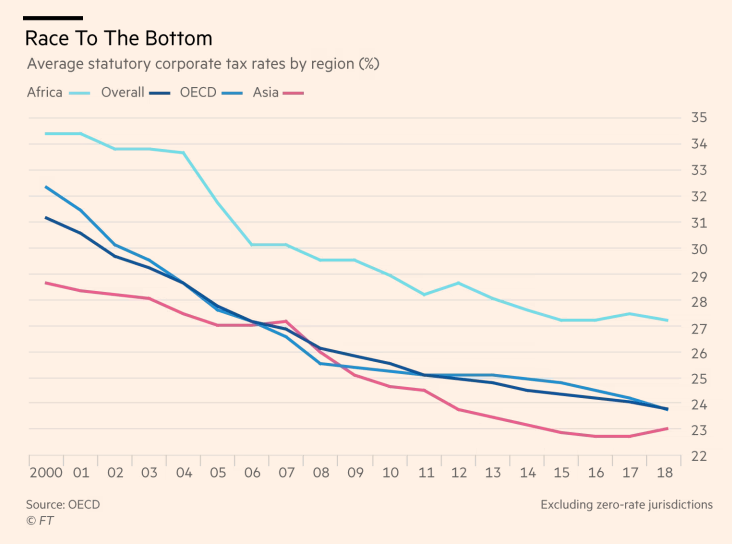

In any case, playing the game of international tax competition means getting locked into a race where the only outcome is zero tax. Each state is caught in a prisoner’s dilemma, forcing it to reduce its tax rates in order to be better placed than its neighbors. The only equilibrium situation is one in which no state is able to raise taxes and therefore incur public expenditure…

Average nominal corporate tax rate by region

Source https://www.ft.com/content/b358ebca-4097-4cd6-bc7f-8e9d8f069250

Taxation reduces economic activity

According to neoclassical economic theory, the fact that taxes generate economic distortions is self-evident, since they influence prices. Prices no longer simply reflect production costs, but obviously also include taxes. This price distortion alters the balance between supply and demand. The mathematical conditions for achieving the “social optimum” – a theoretical state of maximum social well-being – are no longer met.

To simplify, according to the neoclassical model, output is highest when all economic agents are completely free to choose, provided they seek to maximize their individual utility and are not subject to any constraints (regulatory or price). In a large equilibrium game, prices would then naturally reach a level that sets the “right incentives” for everyone. However, introducing a tax gives rise to “artificial” incentives (substituting taxed labor with less-taxed capital, or reducing the quantity of labor because part of income is taxed, for example). These incentives “distort” the economy: it is in this sense that neoclassical theory asserts that taxes create economic distortions.

According to this theory, all taxes have the effect of “distorting” economic activity, with the exception of those whose amount does not change according to our behavior, known as lump sum taxes. In effect, if the state deducts €1,000 from your bank account, regardless of your activity or income, your behavior is not influenced, and the economy remains at its “social optimum”. The problem is, of course, that this type of tax is regressive: wealthier people pay as much as poorer people in absolute terms (and therefore pay less in proportion to their income level). Since flat-rate taxes are rarely desirable, what remains are taxes that influence behavior to a greater or lesser extent. 6 .

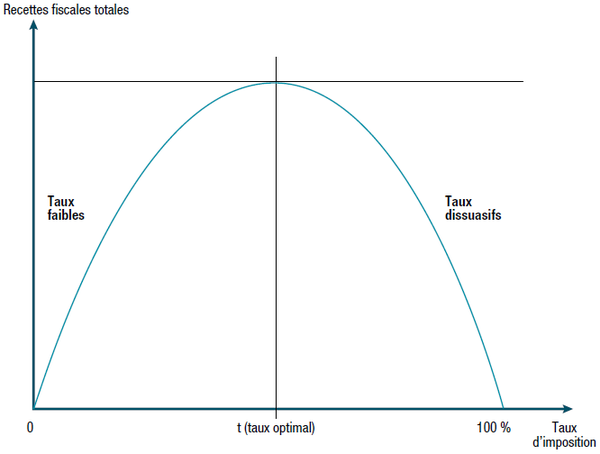

The Laffer curve

If higher taxation implies lower economic activity, some conclude that it is possible for higher tax rates to generate lower tax revenues. This argument, which is another theoretical foundation of supply-side policy, is illustrated by the “Laffer curve”, by the liberal economist Arthur Laffer.

This curve represents the adage “too much tax kills tax”: when the tax rate rises, companies and workers have less incentive to produce or work (because the income they derive from doing so is lower), so production falls. And since tax revenue is the product of the tax rate and the tax base (corporate profits or worker income, for example), revenue may fall if the tax base decreases faster than the tax rate.

According to this curve, starting from a zero tax rate, the tax base decreases less quickly than the tax rate increases. In other words, a one-point increase in the tax rate reduces profits by less than one point, so tax revenues do increase. But beyond a certain threshold, the tax base would fall faster than the tax rate: an additional point in the rate reduces the base by more than a point. Tax revenues then fall. There is thus an optimal tax rate, which maximizes government tax revenues.

The existence of this curve is based on a number of highly simplifying assumptions, and even if it has been observed for a few types of tax and in specific contexts, it is not a general law (there may well be several optimal rates, for example).

Source Find out more in our fact sheet on runoff theory

Supply-side policy aims to make employment more flexible and reduce unemployment

Supply-side policies generally fall into two broad categories: those that aim to make the labor market more flexible while discouraging non-employment, and those that make life easier for businesses, through tax cuts, deregulation and targeted subsidies. In this first section, we focus on measures affecting workers and jobseekers. These are mainly based on three levers: reducing aid to jobseekers, abolishing or lowering the minimum wage, and deregulating the labor market.

Discouraging unemployment

Supply-side theory proposes, firstly, to remove disincentives to work in order to discourage unemployment, and thus produce more. There are three main ways of doing this: reduce the amount of unemployment insurance, shorten the duration of unemployment insurance (secondarily by tightening controls and demands for quid pro quos in order to receive aid), and finally reduce the amount of aid paid in the event of inactivity, once the duration of unemployment insurance has been exceeded.

The idea that unemployment falls when jobseekers are made to feel uncomfortable is borne out by the data. A survey of econometric studies on unemployment insurance 7 concludes, for example, that more generous compensation systematically leads to longer periods of unemployment and a lower probability of finding a new job. At the same time, a longer maximum benefit duration shifts the peak of the benefit exit. On the other hand, this analysis notes that “the peak observed appears much less pronounced, albeit significant, when restricted to job resumption alone”: while some exits from unemployment are indeed due to recruitment, many others are in fact a simple shift to other states that are not employment: minimum social benefits or training, for example(see the work and unemployment module).

Another article published in the Revue d’économie politique 8 while admitting that “the elasticity of unemployment duration with respect to the amount of unemployment benefit is positive, but relatively low”, points out that various “empirical and theoretical contributions have highlighted the potential benefits of unemployment compensation, emphasizing that it also helps finance the search for good-quality jobs”. This is also the thrust of an article by economist Daron Acemoglu 9 who endeavours to show that unemployment insurance improves labour productivity, as it encourages the unemployed to seek more productive employment and thus forces companies to create these jobs.

In short, to imagine that simply reducing the amount and duration of unemployment benefit will reduce the number of people out of work is to take a very narrow view of the mechanisms at work. Unemployment rates are much higher in low-skilled populations. It also varies significantly by region. All of which goes to show that unemployment is more a structural problem of labor market lock-in than a lack of incentive to work. Esther Duflo’s many field experiences also show that “generous unemployment benefits do not discourage people from working”. Work is a way of giving meaning to one’s life, acquiring social status and being part of a community, and jobseekers are therefore not very sensitive to the duration or amount of unemployment benefits they receive.

Reduce or abolish the minimum wage

Neoclassical economists have long argued that a minimum wage is bad for employment. The logic would be that, in a world without a minimum wage, all workers would be hired and paid according to their marginal productivity. However, if a minimum wage were introduced, all workers whose productivity is too low would not deserve this minimum remuneration and would find themselves out of work.

In practice, various studies have investigated the introduction or increase of a minimum wage in several countries and have been unable to observe a negative effect on the unemployment rate. This is the case in Germany, which introduced a minimum wage in 2015, but also in the United States, whose various states have different minimum wage legislation, or in the UK, which has increased the minimum wage since the 2000s, without any noticeable effect on employment (the unemployment rate actually fell during these years). Similarly, the meta-analyses point out that the numerous econometric studies fail to identify a negative causal link between minimum wage and employment.

The purely theoretical reasoning mentioned above is therefore far too simplistic and omits a multitude of factors. First of all, the minimum wage enables some workers to be better paid and therefore to consume more. This additional demand encourages economic activity, which in turn creates new jobs. In addition, it seems that minimum wages force companies to create higher-quality, less repetitive jobs that make employees more satisfied. It should also be borne in mind that, without a minimum wage, many precarious workers have to hold down two jobs at the same time. As a result, they are more stressed, don’t have the time or means to look after themselves properly, and have to bear a mental burden that prevents them from making long-term plans. According to sociologist Matthew Desmond, the minimum wage is “an antidepressant, a contraceptive aid, a healthier diet, a sleeping aid, a tranquilizer”.

Making the job market more flexible

Improving the labor supply (from a company’s point of view) can be achieved by reducing unemployment benefits and lowering the minimum wage, but also by making work itself more flexible.

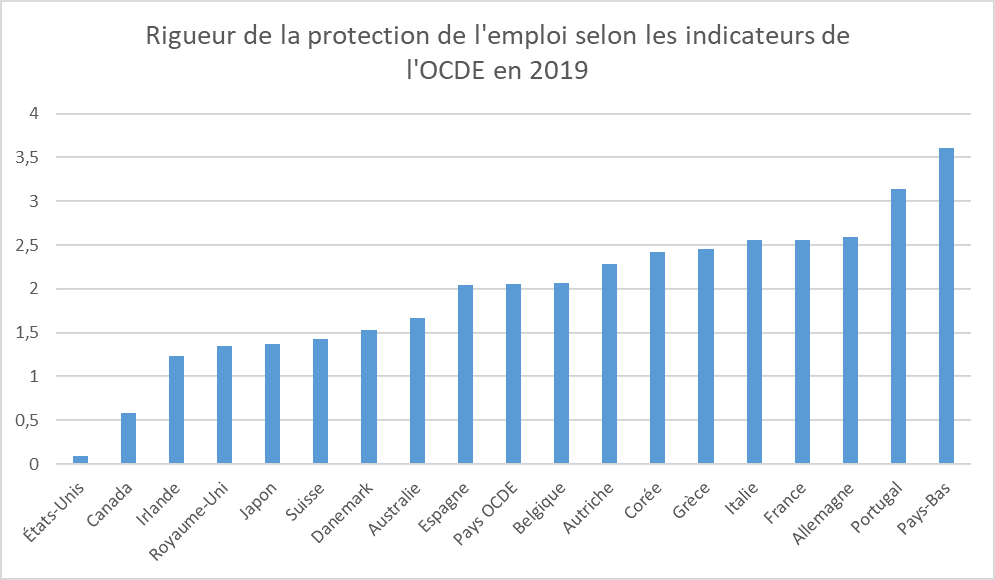

The OECD has devised an index to measure the degree of employment protection, taking into account notification requirements, notice periods and severance pay. It thus expresses the difficulty, in terms of costs and procedures, that an employer would encounter when making an individual or collective redundancy.

Although France is regularly referred to as a country where it’s difficult to lay off workers, job protection is actually stronger in Germany. Furthermore, Italy and other OECD countries have a level of protection very close to that of France. On the other hand, it is clear that employment is much less protected in the Anglo-Saxon countries (USA, Canada or the UK).

According to supply-side theories, job protection is counter-productive, as it discourages companies from recruiting, for fear of having to bear the future cost of redundancies (if the candidate turns out to be unsuitable, or if economic activity slows down).

In practice, these effects are rarely, if at all, observed. A meta-analysis condensed the results of 72 studies and found no statistically significant effect between the level of job protection and the unemployment rate. On the other hand, it did find a small but consistent effect between job protection and the employment rate. 10 .

The International Labor Organization has also looked into the matter, producing a study of the various labor market reforms in 111 countries between 2008 and 2014. The conclusion is surprising: deregulation leads to a slight temporary rise in the unemployment rate.

In a document on employment prospects, the OECD also admits that the empirical correlation between employment protection legislation and employment levels is complex. It points out that many studies fail to demonstrate the existence of the latter, and that the few that do find it have a relatively limited effect. This is also the conclusion of a note by the Conseil d’Analyse Economique.

Supply-side policy advocates lower charges for businesses

In addition to making work more flexible, supply-side policy also advocates easing financial constraints for companies. This means lower taxes, lower labor costs and even subsidies for companies.

Reducing taxes on businesses

Taxes on businesses are a first category of constraints. They reduce their margins and raise the cost of goods sold (thus impacting their competitiveness against competitors not subject to the same level of taxation).

Corporate income tax (based on profits, with net earnings used to pay dividends, finance investments or set aside reserves), tax on productive capital (based on real estate assets, for example) and production taxes (such as the CVAE, which will be abolished in 2023) should therefore have a very low rate, or even zero, to avoid penalizing economic growth.

According to some studies, taxes do have a negative effect on growth. According to a 2012 study on Canada, a one-point reduction in the corporate tax rate would result in 0.1 point improvement in GDP growth 11 while another study for the United States concludes that this would result in a 0.6 point increase in GDP growth 12 . The European Economic and Social Committee, for its part, puts the figure at 0.1 to 0.2 points of additional growth per percentage point reduction in the corporate tax rate.

However, in a meta-analysis published in 2022 13 (441 datasets from 42 studies), the authors highlight the fact that the conclusions of the studies vary considerably: from a significant positive effect on growth, to a negative effect or no effect at all. They conclude that the current literature does not allow us to reject the hypothesis that a corporate tax increase would have a zero effect. In other words, the empirical analysis does not clearly corroborate the theory. 14 .

At this stage, we should note that corporate taxation may have a negative effect on growth, but that if such an effect exists, it is relatively weak and difficult to identify empirically.

Reducing the burden on labor

From a company’s point of view, the cost of labor includes both the wages paid to employees and the social contributions (employee and employer) paid to the State or social security administrations. As the public authorities cannot decide to reduce the wages paid to employees, the only practical way to reduce labour costs is to reduce social security contributions (or the minimum wage, as discussed in section 2.2).

According to the proponents of supply-side policies, lowering charges on labor would have several effects.

- It would reduce costs for companies, enabling them to increase their payroll to produce more.

- Provided that the balance of power between employers and employees ensures that this reduction in charges also benefits employees’ net incomes, it would increase consumer demand, as households derive more income from their work.

- Under this same assumption, it would act as an incentive for workers to work more.

A review of the literature concludes that studies tend to show that lowering charges on labor does indeed have a positive impact on GDP. However, none of them identifies precisely whether this is a demand-side mechanism (workers see their incomes partially increase, and therefore consume more) or a supply-side mechanism. Nevertheless, some studies have shown that the effect of a reduction in labor costs is stronger when it is targeted at the lowest wage earners. This is generally indicative of a demand-side mechanism, as the lowest wages have the highest marginal propensity to consume, and therefore generate greater additional demand per euro of lower taxation.

Support for innovation

Public support for innovation enjoys a relatively solid theoretical justification. Knowledge benefits everyone, not just the economic player who builds and acquires it. The overall economic benefit of an innovation therefore generally exceeds the direct benefits accruing to the company behind it. Economists call this phenomenon “positive externalities”, which should be subsidized, as opposed to “negative externalities”, which should be taxed.

Indeed, while companies have a natural incentive to innovate, this may not be enough, as they weigh up the cost of investment against their own profits. The result can be under-investment in research and development (R&D).

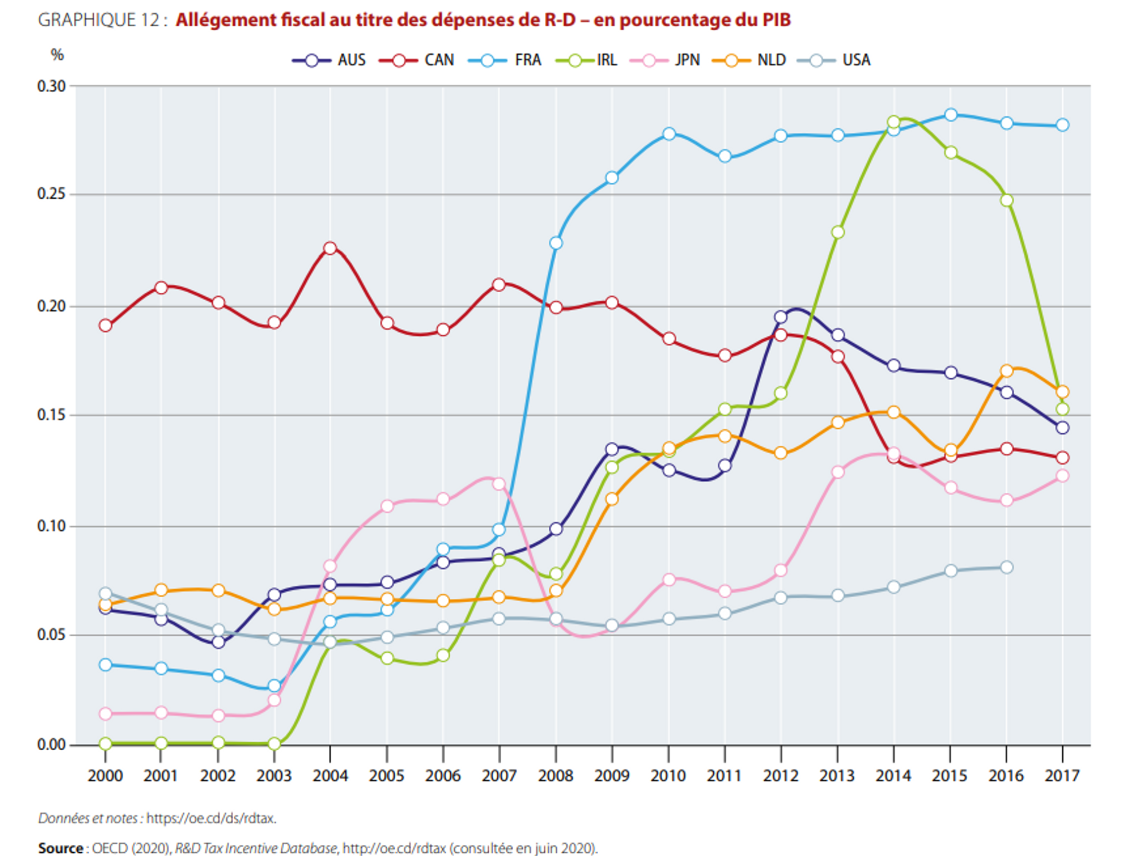

Public support for innovation can take the form of tax credits (such as the research tax credit), subsidies or public orders. 15 .

The ratio of R&D expenditure to GDP was 2.35% in 2020 for France, compared with 3.14% for Germany and 3.45% for the United States. Yet public support for private innovation is much stronger in France 16 than in other OECD countries. This is due in particular to the existence of the research tax credit (crédit d’impôt recherche – CIR), a public aid scheme designed to improve innovation and competitiveness. It allows companies to be reimbursed for 30% of their research expenditure (up to a maximum of €100 million, and 5% above that) via a tax credit on their corporate income tax. 17 . Expenses taken into account are those related to research and innovation (personnel costs for researchers, doctoral students, technology watch costs, patent defense, amortization of acquired patents, etc.). The CIR represented between 6 and 7 billion euros in lost tax revenue per year between 2014 and 2021. 18 .

Unfortunately, the CIR is not achieving the results we had hoped for. According to the Commission nationale d’évaluation des politiques d’innovation (CNEPI), the various studies conclude that the leverage effect of public spending is between 1.1 and 1.5: this means that one euro of CIR leads to 1.1 to 1.5 euros of additional R&D spending, which is relatively low. What’s more, the 2008 reform (which raised the CIR base ceiling from €16 million to €100 million) is said to have resulted in a 5% increase in the probability of a beneficiary company filing a patent. The effects of the CIR are therefore real, but very limited.

The CNEPI also notes that the various economic studies and analyses tend to show that the effects of the CIR are positive for SMEs, but very weak for ETIs and large companies. In fact, SMEs account for only 27% of the total CIR in France. For this reason, the Conseil d’analyse économique, in its report Renforcer l’impact du Crédit d’impôt recherche (2022), recommends targeting the CIR more closely at VSEs and SMEs. One possibility would be to lower the base ceiling (currently 100 million euros) and increase the reimbursement rate (currently 30%), which could be achieved with a constant budget, notes the CAE.

Historical examples show that supply-side policies have had mixed results

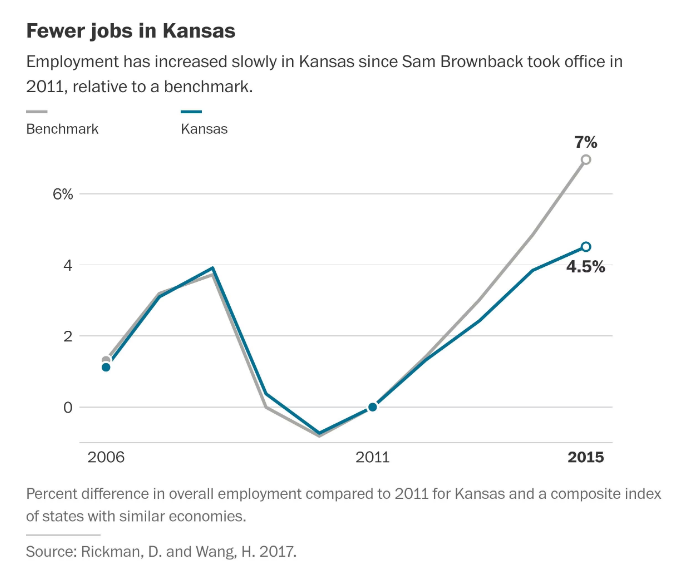

he Kansas example

Kansas elected a Republican governor in 2010. During his campaign, the governor promised to stimulate the state’s economic growth by reducing the marginal income tax rate for the wealthiest to the level of the middle class. This policy was supposed to stimulate investment and encourage the wealthiest to work harder in order to boost economic development. An ex-post evaluation showed that this policy actually had a negative net impact 19 . It would appear that, all other things being equal, this tax exemption increased the unemployment rate, reduced per capita income and slowed growth. One of the reasons for this result is that the State, having collected less revenue, invested less. However, a state that spends is a state that allows its teachers, administrative staff and employees of its service providers to consume. In part, therefore, this demand for consumption did not take place.

Change in employment rate compared with 2011 in Kansas and a counterfactual state

Source Kansas’s conservative experiment may have gone worse than people thought, Washington Post, 2017

The French case of the tax credit for competitiveness and employment (CICE)

The Responsibility Pact is a set of measures pushed by President François Hollande aimed at lowering the cost of labor in France. One of the cornerstones of this pact was the Tax Credit for Competitiveness and Employment (CICE), which came into force on January 1, 2013. This was a public aid scheme designed to reduce the cost of labor by subtracting from the amount of corporate tax or income tax, 6% of payroll paid up to 2.5 times the SMIC (the rate was initially 4% in 2013, then 6% in 2014, 7% in 2017 and 6% in 2018). Since January 2019, the CICE has been replaced by a permanent 6-point reduction in social security contributions. The CICE represented an average of 18 billion less in tax revenue each year over the 2014-2019 period.

According to the 2017 report by the CICE monitoring committee, whose secretariat is provided by France Stratégie, this tax credit had a positive but moderate effect, of the order of 100,000 jobs saved or created over the 2013-2015 period. At the same time, the CICE represented €27 billion less in tax revenue over the years 2014 and 2015, resulting in €270,000 per job created. There are many uncertainties surrounding this estimate, as it is difficult to statistically assess the “counter-factual” (i.e. what would have happened without this measure).

Nor did the evaluations find any effect on investment, R&D or exports. There was probably a positive effect on margins and average wages in the companies most affected by the CICE, notes France Stratégie. In a report published in 2022, the Institut des politiques publiques also confirms that the CICE has had very modest effects on employment. One of the explanations put forward was that, by its nature as a tax credit, the associated reduction in labor costs was offset in time in relation to the payment of wages, and potentially poorly taken into account in hiring decisions and the setting of wage levels. Another possible reason is that hiring decisions are based not so much on labor costs, as on companies’ development prospects and order books.

The German case – the Hartz laws

Adopted in the 2000s, the Hartz laws are a set of measures aimed at reforming the German labor market, which were championed by Chancellor Schröder(see labor and unemployment module). They included a reversal of the burden of proof in the event of a job offer being turned down (the jobseeker now has to prove the unacceptability of a refused offer), better support (paid for by public budgets), the development of assistance to help the unemployed set up their own businesses, and greater local autonomy for the agencies in charge of jobseekers. In short, they have strengthened certain rights of jobseekers, but above all their duties.

Numerous scientific studies agree that the drastic reduction in unemployment that followed (from 13% in 2005 to 7.7% in 2013) is attributable to these reforms.

However, at the same time, the poverty rate rose from 12.2% in 2005 to 16.1% in 2013. The tightening of eligibility conditions for unemployment insurance has therefore weakened a section of the population too far removed from the job market. The growth enabled by this more or less forced return to employment has come at the cost of a sharp rise in poverty. It should also be noted that the reduction in the unemployment rate was not only due to a reduction in the duration and amount of unemployment benefit, but also to an increase in public spending to provide better support for jobseekers. At the same time, growth in emerging countries, led by China, was rising sharply, creating explosive demand for industrial capital goods and cars, Germany’s specialties. Germany’s strong industrialization is therefore not just the result of the Hartz reforms.

Conclusion: there are other ways to stimulate the economy

Supply-side policies don’t seem to live up to their promises. The economic effects of the various levers it suggests are generally weak, or even non-existent or harmful in some cases. In France, despite the accumulation of tax exemption schemes (CICE, CIR, corporate tax cuts), the trade deficit continues to widen, and France’s price competitiveness is clearly not up to scratch. On the contrary, demand-side policy, according to which the economy can only be revitalized by stimulating demand, is increasingly corroborated by empirical literature.

That said, supply-side or demand-side stimulus is always aimed at improving GDP growth, which remains the cardinal point of the measures they promote. It’s worth noting that in this debate, growth is seen as a sufficient objective, regardless of its environmental impact. And yet, if it exists, this additional growth will be all-encompassing. It will favor the construction of heat pumps just as much as the petrochemical industry. Without the conditionality of tax breaks, there is no reason to believe that additional production will have a lower carbon content than at present, or with less impact on biodiversity. The priority today is not to produce more, but to move towards low-carbon production (in terms of carbon, material flows, impact on biodiversity, etc.).

Whether in the name of supply-side or demand-side policy, any tax exemptions and cuts must be conditional on commitments to more sober production. For example, the public authorities could require a detailed carbon balance sheet, together with a decarbonization trajectory that genuinely commits the company, in return for a reduction in labor costs. This is all the more critical given that this tax cut reduces government revenues and thus weakens its capacity to invest in the ecological transition.

Making business support conditional on ecological progress also means strengthening the resilience of the economy. A sober economy, less dependent on the geopolitical vagaries of material and energy flows, and less exposed to climate risks, is probably a much stronger promise of robustness than half a percentage point of additional growth.

- Indeed, there is not one but many supply-side policies, hence the use of the plural. As we shall see, some are concerned with making work more flexible, while others are aimed more at reducing taxation. ↩︎

- Public policy is never “pure” (in the sense that it deals exclusively with supply or demand). This is partly because political leaders have to make compromises. Secondly, supply-side policies can ultimately affect demand and vice versa, since one person’s income is another’s expenditure. For example, short-time working during the Covid crisis directly helped companies; it also boosted the purchasing power of households that were not laid off. In reality, the levers to be activated depend on the economic situation: mobilizing public budgets to stimulate aggregate demand is particularly effective in times of economic crisis (as we explain in the module on public debt and deficits). ↩︎

- Application policies will be the subject of a separate sheet. ↩︎

- According to this indicator, a tax system is competitive when the marginal tax rate is low. ↩︎

- “A neutral tax system is simply a code that seeks to raise the most revenue with the fewest economic distortions. This means that it does not favor consumption over savings, as is the case with investment and wealth taxes. It also means that there is little or no targeted tax relief for specific activities carried out by companies or individuals.” International competitive Index 2021 ↩︎

- There are, however, a few non-incentive taxes that resemble flat-rate taxes, such as property tax and council tax, which are considered to offer very little incentive (you have to live somewhere anyway). ↩︎

- Fremigacci, Florent. ” Evaluating the impact of unemployment insurance on individual trajectories: from theory to practice “, Revue française d’économie, vol. xxvi, no. 1, 2011, pp. 49-95. ↩︎

- Algan, Yann, et al. ” L’indemnisation du chômage : au-delà d’une conception ” désincitative ” “, Revue d’économie politique, vol. 116, no. 3, 2006, pp. 297-326. ↩︎

- Acemoglu, Daron, and Robert Shimer. 2000. “Productivity Gains From Unemployment Insurance”. European Economic Review 44 (7): 1195-1224. doi:10.1016/s0014-2921(00)00035-0. ↩︎

- The unemployment rate refers to the ratio between the number of workers and the number of people who want to work, while the employment rate refers to the ratio between the number of workers and the population as a whole. ↩︎

- Ergete Ferede and Bev Dahlby (2012), “The impact of tax cuts on economic growth: Evidence from the Canadian provinces”, National Tax Journal 65 (3), pp. 563-594. ↩︎

- Karel Mertens and Morten O. Ravn (2012), “Empirical evidence on the aggregate effects of anticipated and unanticipated us tax policy shocks”, American Economic Review 4 (2), pp. 145-181. ↩︎

- Gechert, Sebastian, and Philipp Heimberger. 2022.“Do Corporate Tax Cuts Boost Economic Growth?“. European Economic Review 147: 104157 ↩︎

- The meta-analysis in question does, however, identify a publication bias in favor of research articles that confirm the theory’s intuition. This is a classic bias that meta-analyses can partially correct using statistical methods, which is what this study does. ↩︎

- Economist Mariana Mazzucato, for one, points out that today’s greatest inventions would never have been possible without government investment. Tech giants use technologies developed by the public sector: the Internet (whose ancestor, Arpanet, was financed by the Pentagon), GPS (developed in the 1970s to determine the location of military equipment). ↩︎

- See OECD R&D tax incentives database, 2021 edition ↩︎

- To find out more about research tax credits in France, visit the government website. ↩︎

- See the report Evaluation of the research tax credit – Avis de la CNEPI 2021 ↩︎

- Rickman, Dan S., and Hongbo Wang. 2018. “Two Tales Of Two U.S. States: Regional Fiscal Austerity And Economic Performance.” Regional Science And Urban Economics 68: 46-55. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.10.008. ↩︎