This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

If there’s one term whose meaning is important in today’s world, dominated by the capitalist system, it’s capital. Yet the term is polysemous, and its use can lead to confusion. Here, we attempt to distinguish between the different meanings, depending on the context and discipline concerned. Indeed, as we shall see, depending on whether it is used by economists, financiers, corporate accountants or national accountants, this term designates very different economic realities.

Company capital: the accounting view

What is a company’s “share capital”?

When a company is set up, the founder(s) contribute resources (financial or in kind) to constitute the company’s share capital: they “endow” it with capital. They are said to “subscribe” to the company’s capital when they undertake to pay the corresponding sum, and to “pay up” the capital when they actually contribute the funds.

The share capital is divided into shares, allocated to the founders (henceforth referred to as shareholders) in proportion to their contribution. Ownership of these shares confers the right to participate in decisions taken by the company’s General Meeting, as well as financial rights (via the payment of dividends).

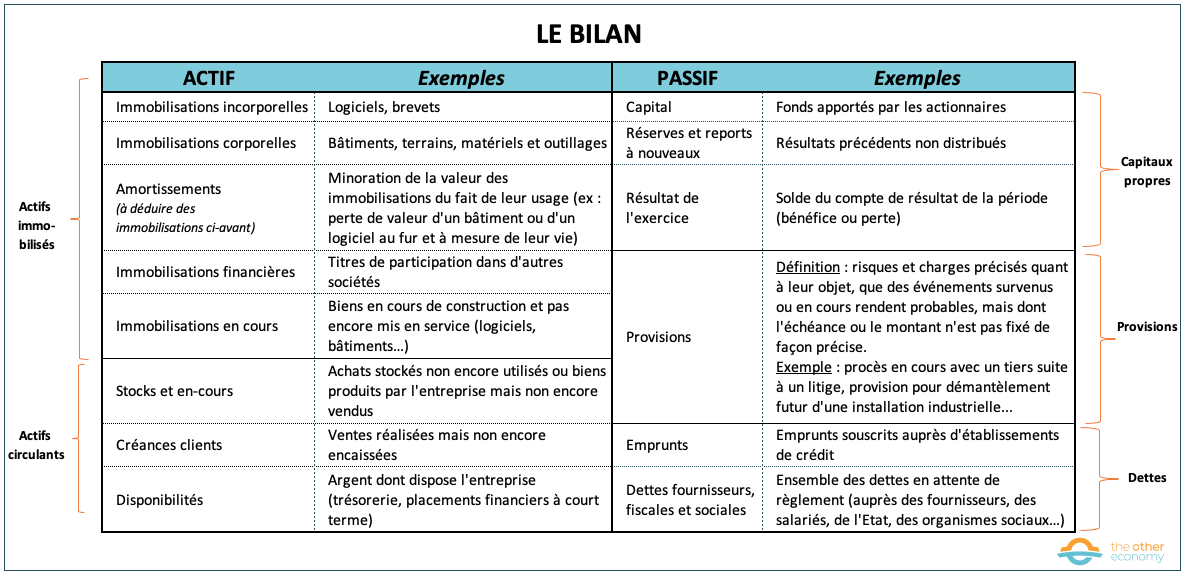

For accounting purposes, share capital is recorded as a liability on the company’s balance sheet (see box).

When the company is created, the capital endowment is entered on the liabilities side, while a receivable from shareholders is entered on the assets side. 1

Equity is one of the company’s sources of financing

Shareholders’ equity is made up of the company’s share capital and annual profits not distributed to shareholders.

So, when a company makes a profit and doesn’t pay it back to its shareholders in the form of dividends, it increases its “shareholders’ equity”. It can also increase it through a new contribution (a capital increase).

In all cases, it remains a company liability.

The entrepreneur calls on other sources of financing: debts, starting with day-to-day management debts (suppliers, customer advances, tax and social security debts) and then, if he is able and willing, bank debts.

All these resources are used to finance asset items:

- tangible assets (land, buildings, equipment, etc.), intangible assets (patents, trademarks, goodwill, etc.) and financial assets (investments in other companies).

- and all other items: inventories, trade receivables, bank current accounts, cash investments (see details in the table above showing a company’s balance sheet).

The book value of a company’s capital may differ from its enterprise value

You might think that the book value of a company’s equity (i.e. the value shown on the balance sheet) would be a good representation of the company’s value. But this is generally not the case.

Firstly, in the event of liquidation of the company, the sums recovered from the sale of assets after payment of liabilities are generally not equal to net assets (the difference between the balance sheet total and liabilities, equal by definition to shareholders’ equity).

In addition, as we have seen, shareholders hold shares which they can sell either through bilateral exchanges (over-the-counter), or publicly on organized markets known as stock exchanges (e.g. the New York Stock Exchange or Euronext).

The market value of all a company’s shares, which is often equated with the value of the company, is not usually equal to the value of its shareholders’ equity either.

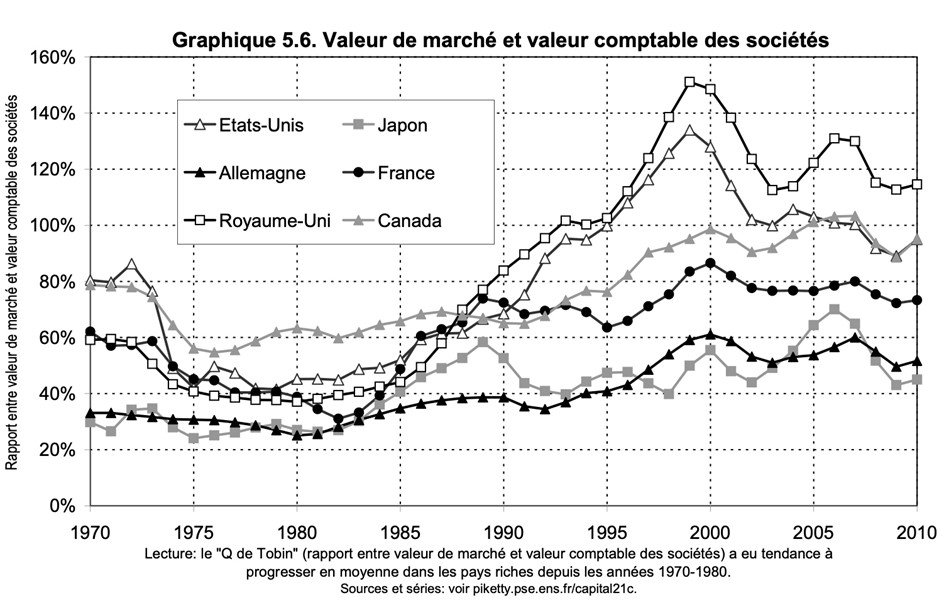

The Price-to-Book Ratio (PBR) measures the ratio between the market value of equity capital (market capitalization) and its book value. The following graph shows that the PBR (sometimes called Tobin’s Q) is the ratio between the market value of equity capital (market capitalization) and its book value. 2 ) is not stable and has tended to increase since the 1970s, reflecting a faster rise in market value than book value.

Ratio of market value to book value of company equity in six countries (1970-2010)

Source Technical appendix to the book Le capital au 21e siècle, available on Thomas Piketty’s website.

Finally, if there are no transactions between buyer and seller, the “value” of a company’s shares cannot be known. However, we may need to estimate it: for tax purposes (in the case of an inheritance, for example), for negotiations prior to a transaction, for the transfer of the company, etc.

There is a wide variety of methods 3 to estimate this value. The best-known is the Price Earning Ratio, which consists of assessing the value of a company’s shares on the basis of an earnings indicator (operating income or net income, for example). 4 ) and multiplying it by a number determined by various parameters (the sector, the company’s growth, its reputation, its prospects, etc.). There is no reason why these methods should produce a result equal to the company’s equity.

As we can see, the meaning of the term “company capital value”, in the absence of precise details, is not without ambiguity.

“Fixed capital”: the national accounts view

The aim of national accounting is to provide a global, quantified representation of the main dimensions of a country’s economy: production, consumption, investment, GDP, unemployment, public debt, foreign debt, national wealth, etc.

In particular, it is used to draw up wealth accounts, which show the assets held and liabilities incurred at a given time by the “national economy” (i.e., all the economic agents or institutional units residing within the national territory – see box). Wealth thus represents, in a way, a country’s stock of “wealth”. 5

Definition: institutional units and sectors in national accounting

Institutional units” (IU) are the basic units of national accounting. In economics, they are referred to as economic agents or actors. They correspond to the various players in economic life: natural persons (households) or legal entities (companies, public authorities, associations), with the capacity to hold goods and assets, incur debt, carry out economic activities and carry out transactions with other units.

An IU is said to be resident from the moment it carries out economic activities on the territory of the country for one year or more. This is not a nationality criterion: an immigrant worker is part of the French national economy, but a Frenchman working abroad is not.

IUs are grouped into five major institutional sectors (themselves divided into sub-sectors) which together make up the national economy: non-financial companies, financial companies, general government, households and non-profit institutions.

Every year, when national accountants draw up their wealth accounts, they report on the state of the national economy’s assets and liabilities:

- Assets are what a country’s economic agents “own”. They can be non-financial (buildings, land, intellectual property rights, etc.) or financial;

- Liabilities are commitments made by economic agents. They are exclusively financial: debts contracted, shares and units in investment funds, derivatives, etc.

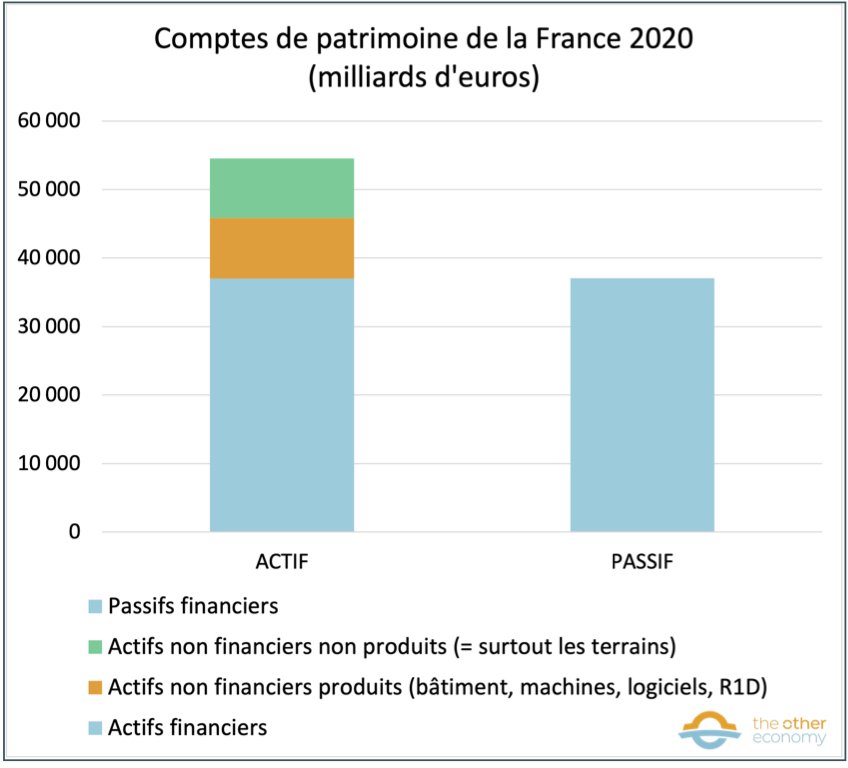

In 2020, the assets of the French national economy amounted to over 54,500 billion euros, a third of which were non-financial assets.

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, table t_8200_2020

In the most general sense of the term, capital in national accounting is the totality of assets

This is what can be read, for example, on the introductory page to the wealth accounts kept by INSEE in France.

“Thanks to their savings, economic agents can accumulate capital, which is measured in terms of year-end stocks of non-financial and financial assets. Non-financial assets are tangible or intangible assets over which property rights can be exercised. Financial assets are economic assets in the form of means of payment or financial receivables. Financial liabilities are debts.

In the sense most commonly used in national accounting, however, capital refers only to a portion of assets.

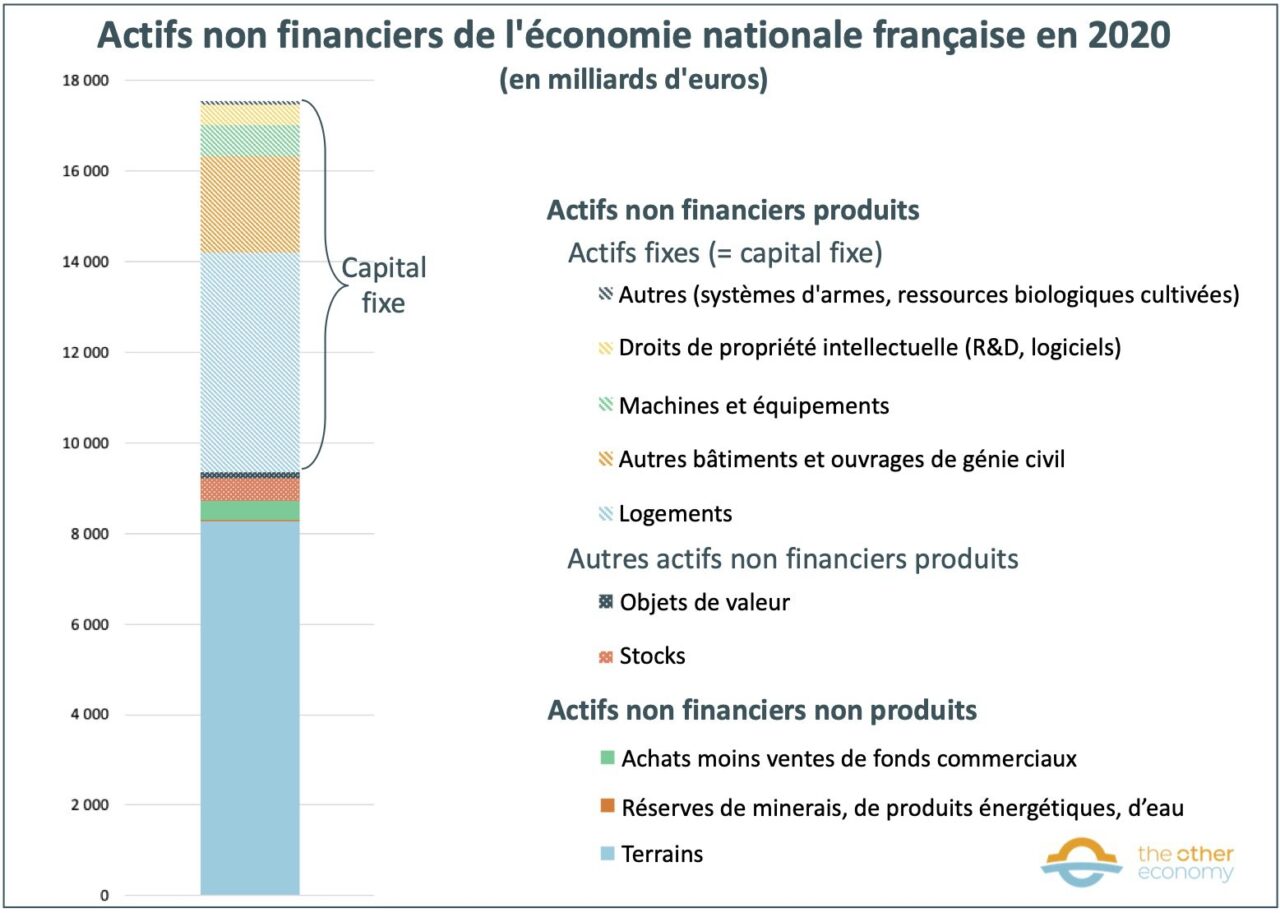

These are “fixed assets”, i.e. goods and services produced for use in the production process for at least one year (these are durable goods) by all economic agents. They may be tangible (buildings) or intangible (research and development).

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, table t_8200_2020

Fixed capital comprises all fixed assets. As can be seen from the graph, it consists mainly of buildings (housing, commercial buildings and civil engineering structures) and, to a lesser extent, machinery (ICT equipment, transport equipment, etc.) and intangible assets (software and databases, R&D).

Note that fixed capital does not include natural resources. They are included in non-produced non-financial assets and are essentially limited to the land value of built-up or farmed land (agriculture, recreational waters).

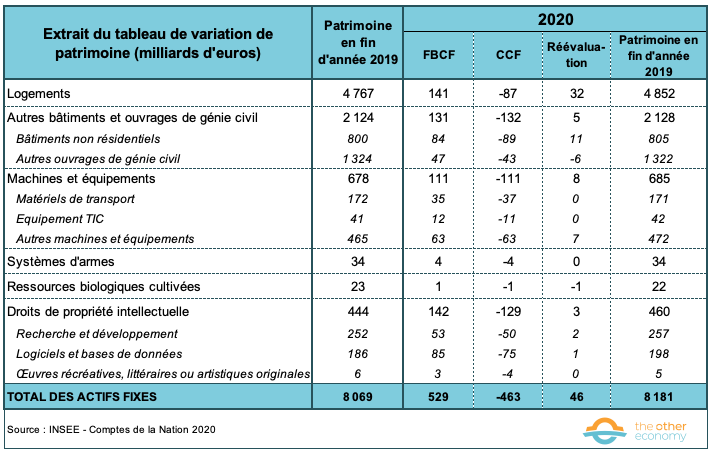

Each year, fixed capital evolves:

- Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) is the name given to the productive investment made over the course of a year by the various economic players. It is made up of acquisitions minus disposals of fixed assets during the year.

- Consumption of fixed capital refers to wear and tear on the stock of fixed capital. Machines, buildings and infrastructure deteriorate over time. Certain equipment (particularly ICT, software and databases) can become obsolete. This is what consumption of fixed capital (CCF) is supposed to measure, but it is very difficult to assess.

- Lastly, fixed capital is revalued in line with price movements (e.g. rising property prices).

Change in France’s fixed assets between 2019 and 2020

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, table t_8211.

National accounts also enable us to report on the wealth, and therefore the fixed capital, of each of the major institutional sectors.

Fixed capital of the five major French institutional sectors in 2020

MISSING DATAVIZ: capital-fixe-des-cinq-grands-secteurs-institutionnels-francais-en-2020Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, table t_8200_2020.

From a national accounting perspective, the fixed capital of companies is an asset (and not a liability, as in business accounting). It corresponds roughly to the tangible and intangible fixed assets counted as assets in business accounting, and therefore includes real estate owned by the company.

For households, this means only dwellings (as well as major home renovation work, which is considered as investment). The other fixed capital items are actually held by sole proprietorships, counted alongside households.

For the State and local authorities, this mainly concerns public buildings and equipment, transport equipment and research and development.

Capital for economists

Economists seeking to explain GDP growth generally use models linking production to the factors of capital and labor.

For example, the Cobb-Douglas function can be written as follows for these two factors:

where :

- Y corresponds to the level of production (GDP)

- K to capital

- L to that of work

- c, α and β are constants determined by the technology.

The first question is: what is K and how is it valued? In the above equation, we’re talking about “productive capital” (i.e. the tangible and intangible fixed assets of companies), not real estate capital (except for the productive part, such as warehouses in the logistics or distribution world) or the other components of wealth.

Economists’ capital is therefore best considered as a component of corporate assets, and at the macroeconomic level as the fixed capital of non-financial companies (excluding non-commercial real estate).

But that’s not always the case.

Economists’ capital can sometimes encompass a very different reality from companies’ assets

For example, in his book Le capital au XXIe siècle economist Thomas Piketty analyzes statistics on household wealth (financial and non-financial). 6

He writes: “In the context of this book, capital is defined as all non-human assets that can be owned and exchanged on a market (p. 82) (…) It thus encompasses all forms of wealth that can a priori be owned by individuals (or groups of individuals) and transmitted or exchanged on a market on a permanent basis. In practice, capital can be owned either by private individuals (referred to as private capital), or by the state or public administrations (referred to as public capital)” (p. 83).

According to Thomas Piketty, capital is not productive capital, and differs from it both conceptually and in terms of numerical analysis. In particular, the value of a company’s shares is a priori different from that of its fixed assets.

Economists can also take an interest in “natural capital”.

It includes :

- natural resources (fossil fuels, minerals, plants, animals, etc.) seen as means of producing goods;

- ecological services: climate stabilization, oxygen production, natural water purification, erosion prevention, crop pollination, “cultural services” (including all outdoor sports and leisure activities, which include enjoying the beauty of the landscape).

This natural capital is not accounted for in company balance sheets (with the exception of land), nor in national heritage accounts (as it is not considered an economic asset in the approach adopted). However, to do without this natural capital in economic terms is obviously strictly impossible.

Capital in Marx’s sense

For Marx, the term capital has a very specific meaning, far removed from anything we’ve just presented. Above all, it’s a type of social relationship, one that capitalists maintain with workers, enabling them to own and accumulate wealth.

Wikipedia’s article on capital (consulted on 05/19/2022) states: “The material means of production (machines, etc.) are not capital by their very nature; they only become capital when they are used by wage-earners and generate surplus value” (J. Bonœur and H. Thouement, 1989), and thus profit. Consequently, for Marx, “instead of being a thing, capital is a social relationship between people” (Capital, 1867). This social relationship corresponds to what Marx calls “capitalist exploitation”.

For Marx’s heirs, capital (or “big capital”) sometimes refers to the “social class” of capitalists.

The financiers

In the world of finance, capital is money used to… make money. Capital markets”, for example, are markets where “financial instruments” (not machines, buildings or natural resources) such as stocks and bonds are traded over the long or short term.

Depending on the case, the distinction can be made according to the nature of the money invested: equity, debt or quasi-equity. 7 But in all cases, in this community, capital is not used in the sense given by economists or accountants.

Conclusion

The purpose of this quick overview is simply to clarify the different meanings of an important term in economic reasoning. How, for example, can we assess the “return on capital” if we don’t know what we’re talking about? Clarifying this meaning is also essential if we are to grasp the major political and social issue of the relative evolution of capital and labor income.

In ecological terms, the lack of integration of “natural capital” into thinking is undoubtedly one of the causes of its failure to be incorporated into public policy. But reintegrating it is no simple matter. Many avenues (in corporate accounting 8 national accounting or economic doctrines and models) are currently being explored.

- When the capital is “paid up” (i.e., the shareholders actually pay the sums promised), this is reflected on the assets side by an increase in the company’s cash position, which balances the receivable and is generally quickly used for the company’s initial purchases. ↩︎

- In reality, the two indicators are somewhat distinct. Tobin’s Q is the ratio of the

market value of assets to the replacement value of assets (often equated with net book value). The PBR relates themarket value ofequity to its book value. But the conclusion is the same: market values are distinct from book values. ↩︎ - See for example Jean-Etienne Palard, Franck Imbert, Le Guide pratique d’évaluation d’entreprise, Eyrolles, 2013. ↩︎

- Operating income is the difference between operating revenues and expenses. Net income is the difference between all revenues and all expenses (the “final” result). In the module on business accounting, we introduce the intermediate management balances table, which provides an understanding of the different types of accounting result for a company. ↩︎

- Wealth is understood here in a restrictive sense, since it only includes assets that can be the subject of market transactions. This excludes many elements that make up a country’s wealth: the skills and training of its workers, its natural heritage, its natural public domain, its architectural and artistic heritage, the quality of its public services, and so on. ↩︎

- This methodological choice has earned him heavy criticism. See, for example, Laurent Thévenot’s article, ” Did you say “capital”? Extension de la notion et mise en question d’inégalités et de pouvoirs de domination “, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 2015/1 ↩︎

- Quasi-equity refers to financial resources that do not have the accounting status of equity, but are similar to it. They include shareholders’ current accounts, convertible bonds and participating loans. ↩︎

- See the work of the Ecological Accounting Chair and the accounting module. ↩︎