This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Purpose and statement of the proposal

Reform European economic governance, and in particular the Stability and Growth Pact, so that economic policy coordination is no longer exclusively centered on the budgetary surveillance of States, but is put at the service of ecological transition (notably by facilitating transition investments).

Perimeter

European Union

Type of measure

Political and Budgetary

Argumentation and justification

Stability and Growth Pact rules hinder ecological transition

The Stability and Growth Pact, at the heart of European economic governance

Gradually built up since the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, European economic governance today aims to enforce budgetary discipline among member states, facilitate coordination of their economic policies and prevent macroeconomic imbalances.

Since 2011, it has been part of the “European Semester”, the name given to the annual cycle of coordination of member states’ economic policies. The semester integrates different processes from different periods into a single calendar.

- The Stability and Growth Pact, launched in 1997, has long been the almost sole object of European economic governance. Its aim is to impose budgetary discipline on member states (see box).

- In 2011, surveillance of macroeconomic imbalances was introduced alongside budgetary surveillance. The 2007-2008 crisis had highlighted the inadequacy of budgetary rules alone in assessing the risks to the EU’s economic and financial stability.

- Coordination of employment policies is limited to the annual publication of a joint report on employment by the Council and the European Commission, as provided for in the Treaties.

- Lastly, the Van der Leyen Commission, which takes office in 2019, has decided to integrate environmental issues into the European Semester. At this stage, it is essentially a question of integrating ecological policy measures into the reports produced by the States, and of filling in the tables of sustainable development indicators.

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP)

Launched in 1997, the Stability and Growth Pact sets out in various legal texts the main principles of budgetary surveillance for member states, as enshrined in the European treaties since the Maastricht Treaty.

In particular, it aims to ensure compliance with two budgetary rules: the deficit must be below 3% of GDP, and public debt must not exceed 60% of GDP.

The Pact is divided into two parts:

– the preventive part sets out the arrangements for budgetary surveillance, as well as the provisions designed to prevent non-compliance with the rules;

– the corrective part details the “excessive deficit procedure” (EDP), which is initiated against a State that does not comply with the rules, and can lead to sanctions (including financial sanctions).

Given the difficulty of enforcing these (seemingly simple) rules, the two original European Regulations (1997) have been amended three times (2005, 2011 and 2013) and supplemented by increasingly complex interpretative guides.

Source Find out more in our European economic governance fact sheet fichegouvernanceue

European economic governance is ill-suited to the EU’s ecological and social objectives

In an economic and monetary union (for the euro zone) where states are highly interdependent, the coordination of economic policies appears to be a necessity. At this stage, however, European governance is too focused on monitoring public finances, neglecting the EU’s other strategic challenges, be they economic, ecological or social.

Budgetary procedures and indicators are paramount

European economic governance is based on an assessment of the economic situation of the Union as a whole, as well as that of each member state. The aim is to converge economies and, above all, to assess debt sustainability. 1. Due to the predominance of the SGP, this assessment and the resulting recommendations are overly focused on budgetary issues.

It’s true that since 2011, other macroeconomic imbalances 2 are monitored and included in each country’s analysis. However, they carry less weight than those relating to public finances:

- the reference values chosen for the indicators concerned are alert thresholds and not targets to be reached, as is the case for the public deficit and debt;

- analysis of public finances accounts for the bulk of exchanges between the Commission and individual Member States;

- each year, Member States publish two separate documents as part of the European Semester: the national reform program presents the main economic measures and reforms undertaken or planned; the stability program focuses on public finances.

- the excessive deficit procedure is triggered almost automatically, whereas a detailed judgment is required for the excessive imbalance procedure.

Moreover, social and ecological issues are virtually absent from the analysis. With the exception of the employment indicators included in the dashboard for monitoring macroeconomic imbalances, social and ecological indicators are not subject to any particular monitoring or procedure.

Budgetary rules are a source of economic imbalances

States’ budgetary rules must allow public debt to evolve in a way that does not lead to an explosive interest (and repayment) burden, while leaving decision-makers room to smooth economic cycles and support employment and economic activity when private demand is unsatisfactory.

Experience has shown that the Stability Pact and European rules do not meet this requirement satisfactorily. In particular, they have proved to be pro-cyclical, with a deflationary bias.

These criticisms are not new, and have given rise to numerous attempts at reform (in 2005, 2011 and 2013), so far without success. On the contrary: successive amendments to the Stability and Growth Pact have only made the rules more complex and disconnected them a little more from economic reality, by basing them on unobservable indicators (see our fact sheet on potential GDP and the structural balance ).

Budgetary rules are an obstacle to the ecological transition

In addition to the economic reasons already sufficient to justify reform, there is the urgent need for massive investment in the ecological and energy transition over the next three decades.

This transition is an obligation sealed between the member states of the European Union by the adoption of the Green Pact for Europe. The investment required is not optional: failure to make it would lead to a serious and irreversible deterioration in the material conditions of human activities and the very habitability of the planet.

The needs are massive. At the end of 2021, in a communication, the European Commission estimated the additional investment needed to achieve the EU’s ecological objectives at over 500 billion euros per year. Much of this investment will be financed little or not at all by the private sector: hence the need to draw on public budgets. 3.

However, the budgetary rules that currently form the core of European economic governance are detrimental to public investment (and more generally to public financing), since they encourage cuts in public spending, regardless of the quality of the expenditure concerned. They are therefore a major brake on the ecological transition.

Find out more

Critical analyses of the budgetary rules of the Stability and Growth Pact, and more generally of European economic governance.

- European budgetary rules are not economically rational, module on public debt and deficit (TOE)

- How to improve the Stability and Growth Pact through proper accounting of public investment, Olivier Blanchard and Francesco Giavazzi (2004)

- Reforming Fiscal Governance in the European Union, IMF, 2015

- Assessment of EU fiscal rules, report by the European Budget Committee commissioned by the Commission (2019)

- Annual Report 2020 of the European Budget Committee

- Redesigning EU fiscal rules: From rules to standards Olivier Blanchard et ali, Working Paper PIIE (2021)

- Europe should not return to pre-pandemic fiscal rules, Joseph Stiglitz, Financial Times (2021)

- Interview with Klaus Regling (one of the fathers of the Stability and Growth Pact) Director of the European Stability Mechanism (2021)

The main principles of a reformed Stability and Growth Pact

In February 2024, the Parliament and the Council reached an agreement in principle on the terms of the reform of European economic governance. The European Parliament plenary still has to approve the text in April, bringing to a close a process that began more than four years ago.

During this period, very different visions of economic governance, and more generally of the European Union, came into conflict. Some of the proposals (on which this note is based) were ambitious, aiming for “a far-reaching reform of the EU’s economic governance framework, to ensure that reformed budgetary rules are consistent with the Union’s social, climate and environmental objectives”.4. Others, supported by certain Member States and a number of experts, continued to make budgetary rigor the structuring element of economic policies.

Unfortunately, the latter are likely to prevail. Adoption of the new framework resulting from the February agreement would not fundamentally call into question the logic that gives pre-eminence to the budgetary rules laid down over thirty years ago over all other considerations. 5.

This lack of progress is such that some commentators, such as Olivier Blanchard, claim that the new rules are obsolete even before they come into force. It is to be hoped that a majority of the European Parliament will reject the text in April and get back to the drawing board!

Integrate the EU’s ecological and social objectives into all stages of European economic governance

A “transition and budgetary programming programme” replaces the two annual programme documents produced by the Member States during the European Semester.

Indeed, it is problematic to analyze separately the trajectory of public finances and the other economic policy measures (regulatory, administrative and fiscal) that largely determine the effectiveness of budgetary commitments.

This rolling five-year program would be adjustable annually to take account of unforeseen circumstances, implementation or changes in political majorities. Its core would be the medium/long-term programming of financial commitments in favor of a fair ecological transition, as well as the reduction of environmentally unfavorable spending.

This document would therefore form a bridge with the various existing sectoral strategies and programs (such as the National Energy and Climate Plans), which are currently dealt with in silos in each dedicated department (at the Commission or in national ministries) and do not, or too little, feed into European economic governance. The framing of public finances can no longer be considered independently of these effects on transition.

National programs would be assessed on the basis of their contribution to major European objectives. This includes not only the macroeconomic dimension (sustainability of the public debt path, response to cyclical economic variations, contribution to the convergence of European economies), but also the ecological and social dimensions enshrined in the Green Pact and the European Charter of Fundamental Social Rights. pMore details on the methodologies to be employed in section 2.4.

A single procedure for monitoring “economic, social and environmental sustainability” has been introduced

The aim is to merge the two major current mechanisms: the budgetary surveillance of the Stability and Growth Pact and the budgetary surveillance of the Stability and Growth Pact. 6 and the surveillance of macroeconomic imbalances. It makes no sense to deal with macroeconomic imbalances and the budgetary policies that are a major determinant of them in separate procedures.

The new procedure would be based on a scorecard, paying equal attention to the costs and risks generated by social, ecological, monetary and financial imbalances. It would therefore include not only indicators alerting to the emergence of imbalances jeopardizing economic and financial stability and the convergence of European economies, but also those focusing on social and environmental sustainability in line with European objectives.

Exceeding alert thresholds would trigger an in-depth dialogue between the European Commission and national authorities. At the end of the dialogue, the Commission would submit to the Council and the European Parliament draft conclusions on the appropriateness of corrective measures and amendments to the national transition and budget program.

Governance that enables public debate

Today, European economic governance is an obscure, highly technical subject, not easily understood by the general public, yet fundamental to the orientation of public policies and therefore to the lives of citizens.

The various measures outlined above are designed to simplify the European semester and the various procedures involved. At the same time, we need to place clear, coherent economic, ecological and social objectives at the heart of this governance. These conditions are necessary to enable democratic debate and, ultimately, the political legitimacy of common rules.

Beyond the transparency and legibility of objectives and rules, it is of course also important to set aside time for public debate, in particular during the submission of transition and budget programming programs. When alert thresholds are exceeded, the country concerned could also initiate a phase of public debate, with the participation of social partners and all relevant stakeholders, particularly in environmental matters. The debate would be fuelled by data on the assessment of imbalances and risks. Its aim would be to feed the dialogue between the commission and the state concerned.

A new approach to monitoring and steering public finances

The aim of budgetary surveillance is to ensure debt sustainability, i.e. that governments are able to meet their obligations to their creditors.

The main indicators on which this assessment (and the discourse relayed in public debate) is based are quantitative: debt/GDP, deficit/GDP, expenditure/GDP.

However, other information is needed to assess a country’s budget management and debt sustainability. 7 These include the level of public assets, the cost of debt, the current account balance and the monetary sovereignty of the state concerned. The more or less favorable economic situation must also be taken into account in the analysis. Taken together, these dimensions show just how problematic a uniform numerical rule for 27 states is.

In addition, the quality of public spending is also fundamental: what impact does it have on economic policy objectives? and above all, does the debt serve to prepare for the future? At this stage, the question of quality is only addressed at a later stage, and without taking ecological and social issues into account (see box).

The reform must therefore take these different dimensions into account.

Potential GDP” at the heart of assessing the quality of public spending

Flexibility clauses” allow derogations from the budgetary rules of the SGP either to deal with unforeseen events 8or to improve the quality of economic policies and public spending.

>The “structural reform clause” justifies a temporary deviation from a country’s budgetary target in order to implement reforms likely to reduce public spending over the long term, or to boost “potential GDP”. Here are a few examples from the SGP application guide: pension, health insurance and public administration reforms, and those aimed at making the labor market more flexible.

>The “investment clause” does the same for investments with an expected and verifiable impact on “potential GDP” (and benefiting from European co-financing). Very complex to justify, this clause is hardly used in practice.

Source Find out more about flexibility clauses in our fact sheet on European economic governance.

Broadening and renewing the assessment of debt sustainability

Instead of being based, as today, on common numerical rules, the assessment of debt sustainability would take into account the economic realities of each country (public assets, interest rate levels, private debt) and would be based more on the evolution of the cost of debt for public finances.

Finally, particular attention would be paid to climate and ecological budget risks, i.e. the impact that under-investment in the ecological transition could have on public budgets.

Governments will have to assume the political nature of this assessment. The new governance will have to open up spaces for political choices that have become more complex, including from the point of view of intergenerational justice, between stabilization, indebtedness and the financing of ecological policies.

Implementing an “ecological and social golden rule

Many of our proposals aim to introduce an “ecological and social golden rule”, giving priority to certain categories of expenditure (investment in particular) to prepare for the future.

From a technical/legal point of view, several options are on the table. Some envisage making existing flexibility clauses more flexible; others deduct all or part of “green” expenditure from deficit and debt calculations. A recurring proposal is to align public accounting with private accounting. 9 and to include only investment depreciation and maintenance in the calculation of the current deficit, by creating a separate account for capital expenditure.

These various proposals require precise identification of the expenses eligible for the golden rule.

A number of regulations and research projects are underway to qualify economic activities or public spending as “green” (see box). There is, however, nothing equivalent in the social sphere. These approaches are interesting, but far from sufficient.

Green budgets and taxonomy: technical approaches

Green budgeting” work 10 aims to categorize each item of public spending according to its positive, negative or neutral impact on the environment.

To this end, public players can refer to the recent European taxonomy. This lists, according to criteria that are in principle purely technical, the economic activities that contribute to achieving one of the six environmental objectives. 11 without harming the others.

It is a tool designed for investors (private or public) who want to direct their financing towards economic activities that protect the environment or benefit the transition.

Beyond the difficulty of reaching a consensus on what is green and what is not 12taxonomy and “green budgets” are technical tools that are no substitute for strategy.

The environmental effectiveness of an expense depends on the regulatory, fiscal and financial context in which it is implemented, as well as on the behavior of the private players involved, and possibly on complementary expenses.

Funding research into alternatives to pesticides is technically a “green” measure. However, if nothing else is done to transform the agricultural model, this funding will have little or no impact on the ecological transition?

The sprinkling of small “green” budgetary outlays that are not part of an overall strategy is akin to greenwashing: the overall amount can turn out to be significant for very little impact.

Putting the budget tool at the heart of a global just transition strategy

Establishing an “ecological and social golden rule” means basing expenditure eligibility on its contribution to coherent public action aimed at accelerating a fair ecological transition.

To put it plainly, the spending involved must be part of a strategy that goes from overall objectives to means of action, and goes beyond budgetary issues alone. Indeed, the ecological transition requires the mobilization and coordination of all economic policy tools: fiscal policy, monetary policy, prudential policy (standards, regulations and bans).

Secondly, it’s important to define a common methodology, while leaving plenty of scope for national political choices on the path to follow.

As indicated in point A, national transition and budgetary orientation programs would provide a synthesis between thematic or sectoral strategies and overall economic policy programming.

For each sector, we need to identify the relevant indicators for monitoring and evaluating the achievement of objectives.

- results indicators, based on physical and social data, which concretely translate the ecological and social objectives to be achieved (greenhouse gas emissions from a given sector, use of chemical products, land artificialisation, employment rates, inequalities, etc.);

- the structuring parameters that constitute the major levers to be mobilized to achieve the ecological and social objectives of the sector concerned. For example, Carbone 4 has identified three structuring parameters on which to act to reduce CO2 emissions in housing (see box below);

- public policy measures to influence these structuring parameters.

This is the framework within which we need to consider the quality of public spending, as well as regulatory, fiscal and administrative measures, and coordination with monetary and prudential policies. Indeed, it is important to design an approach that includes all measures, and not just the budgetary aspects.

An example of how objectives can be translated into policy measures

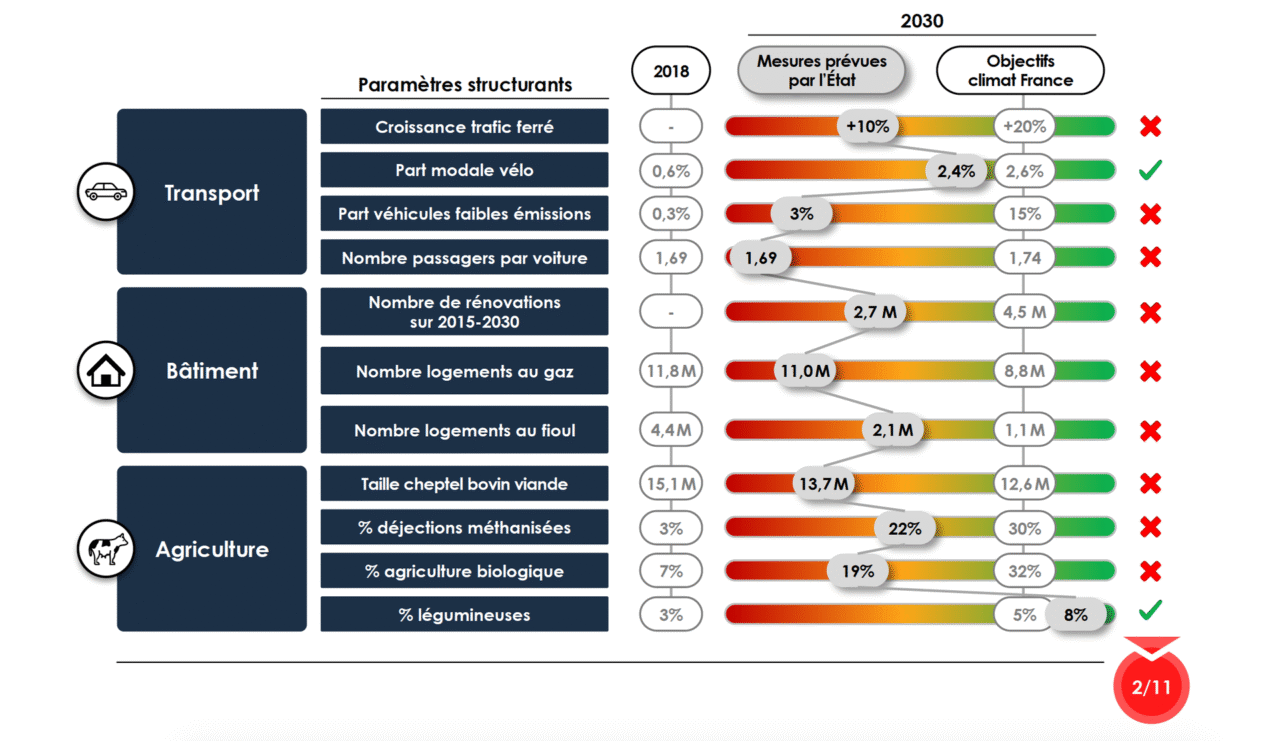

The authors of the study L’État français se donne-t-il les moyens de son ambition climat? (2021) have identified eleven structuring parameters for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in three key sectors (passenger transport, housing, agriculture).

They then analyzed the extent to which the measures taken by the State (including budgetary measures) made it possible to achieve the necessary levels for each parameter.

The summary of the study’s results shows just how inadequate the measures put in place by the French government are in achieving France’s climate objectives.

Work and support for the measure

We list below various initiatives and publications that are consistent with the main thrust of the proposal set out here, i.e. the much more thorough integration of the just transition objective into European economic governance. This does not mean that they validate the details of what is said here.

Appeals and open letters from civil society

- CALL Let’s liberate green investment! (2018) signed by 160 economists

- “Reshaping fiscal framework”, open letter to European leaders from 68 European NGOs and trade unions, supported by a hundred academics (2021)

- Call: A resilience and solidarity pact to replace the Stability and Growth Pact (2021)

- Manifesto for a green, fair and democratic European economy (2022).

- “Time to get it right: EU fiscal rules reform risks going wrong”, statement by the Fiscal Matters coalition (Nov. 2023)

Reform proposals including ecological and social issues

- Unleashing green investment (the dossier), 2018

- Agir sans attendre – Notre plan pour le climat, Alain Grandjean, Kevin Puisieux, Marion Cohen, Les liens qui libèrent, 2019.

- The reform of the EU fiscal framework, position of the Climate Action Network (CAN europe) 2021

- Fiscal Policy for a Thriving Europe – A Feasibility and Impact Analysis of Fiscal Policy Reform Proposals, ZOE Institute (2021)

- What European budgetary framework for the ecological transition?Ollivier Bodin, contribution to the FNH Think Tank (2021)

- Greentervention’s reform proposals (2021)

- Revising the European Fiscal Framework, F. Giavazzi, V. Guerrieri, G. Lorenzoni, C.-H. Weihmuller, (2021)

- A green fiscal pact: climate investments in time of fiscal consolidation, Z. Darvas, G. Wolff, (2021)

- Note on the quality dimension of budgetary rules, Ollivier Bodin (2022)

- Breaking The Stalemate: Upgrading EU economic governance for the challenges ahead, Finance Watch (2022)

- Fiscal rules: identifying green spending and promoting transition, Greentervention (2022)

- European economic and budgetary governance and climate change: applying the precautionary principle to climate risks, Ollivier Bodin (2022)

- Investing in our Future, Seven EU economic governance reforms for a stronger, greener and more resilient Europe, Coalition Fiscal Matters (2023)

Feasibility (legal and political)

The reform of Europe’s economic governance can be envisaged at three levels:

- at Treaty level (European economic governance is based primarily on Articles 121 and 126 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, as well as on Protocol No. 12 – find out more in our dedicated fact sheet).

- secondary legislation, i.e. legislative acts (regulations, directives, decisions, etc.) adopted in application of the European treaties (the main texts concerned are presented on our dedicated page).

- interpretative documents, i.e. non-legislative documents that provide guidelines and interpretations of the Covenant (Vade-mecumthePSC Code of Conduct and the Two-Pack).

The level of the Treaties seems unattainable in the short term, since it requires unanimity, which will not be obtained on such subjects, either because of opposition from one of the so-called “frugal” countries, or because of the countries currently in tension with the rest of the Union on the question of human rights.

The interpretative level is the most accessible, as the Commission seems rather “alluring” on the reform of the Pact and governance. It would be a pity, however, not to be more ambitious and target secondary legislation, which has been amended several times since the signing of the Maastricht Treaty.

The proposals we are putting forward here fall into this category, since they involve amending/merging most of the legislation transposing Article 121 of the Treaties. All depends on political will, which is far more feasible than amending the Treaties, since the proposed reforms require only a revision by qualified majority.

Link to the rest of the platform

To better understand this measure, we recommend the following readings.

In the modules :

- The module on public debt (and in particular the part on the lack of rationality of European budgetary rules; or that on debt sustainability)

- The Role and limits of finance module, and in particular the sections dealing with the inadequacy of private finance to drive the ecological transition (Markets won’t finance the ecological transition on their own(Essential 10); “Green” or “sustainable” finance would be sufficient to achieve the ecological transition(Myth 5); It would be enough to switch funding from carbon-based industries to ecological projects(Myth 6).

In the cards :

- Debt sustainability refers to a debtor’s ability to generate sufficient resources to meet its obligations to creditors (i.e. pay interest and repay principal). Find out more in the module on public debt and deficit. ↩︎

- The dashboard of the macroeconomic imbalance warning mechanism comprises 14 indicators, 10 of which cover external imbalances (external position, exchange rate, competitiveness) and internal imbalances (land prices, financial sector, public and private debt), and 4 employment indicators added in 2015. ↩︎

- To find out more about investment needs and the importance of public funding, see the proposal ” Launching an ecological reconstruction plan “. ↩︎

- Extract from the Manifesto for a green, fair and democratic European economy (2022). ↩︎

- For a quick analysis of the adopted text, see the position of the #FiscalMatters coalition Time to get it right: EU fiscal rules reform risks going wrong, or the analysis of Greentervention, an NGO specializing in this area. ↩︎

- Firstly, the preventive aspect, then the corrective aspect (because, unlike the preventive aspect, amending the legislative texts on which it is based requires unanimity). ↩︎

- Find out more about the relevant criteria for assessing debt sustainability in the module Public debt and deficits. ↩︎

- It was by activating the general derogation clause that the European Commission was able to suspend the rules of the SGP in March 2020, so that European states could deal with the pandemic. ↩︎

- The calculation of the public deficit is similar to that of a cash requirement: capital expenditure is charged in full to the deficit of the year in which it is incurred. In private accounting, investment costs are amortized over the useful life of the investment. It is therefore spread over all the years concerned. ↩︎

- For a progress report on this work in 2021 see Green public finances. Between budgetary ambition and fiscal-social reality Robin Degron (2021), What is green budgeting European Commission (2021) ↩︎

- For the moment, only activities contributing to the first objective “climate change mitigation” have been identified in the taxonomy. The other objectives are: adaptation to climate change, protection of aquatic and marine resources, transition to a circular economy, protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems, and pollution prevention and control. ↩︎

- The debates surrounding the inclusion of gas and nuclear power in the European taxonomy show just how political and subject to pressure this issue is. ↩︎