This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

To understand unemployment, we need to broaden our perspective and not limit ourselves to today’s dominant microeconomic vision. 1 which focuses on the difficulties of matching job supply and demand 2 . While labor market analysis can provide useful insights for short-term measures, it cannot help us understand the paradox of today’s mass unemployment. For hundreds of thousands of years, humanity has lived with scarcity and the risk of famine. Simply put, there was always a shortage of manpower. The thermo-industrial revolution, followed by mechanization, automation, computerization and robotization have, in theory, overcome this curse. 3 . To a large extent, it is machines that work in our place, or help us with the most thankless tasks. The liberation from this age-old yoke, the victory over scarcity and the creation of a world of potential abundance have not, however, entirely succeeded in transforming constrained time into free or chosen time; the result has been unemployment, underemployment or precarious work, with all their attendant social and psychological suffering. In this module, we will attempt to elucidate this paradox, while highlighting a few preconceived ideas.

The essentials

To characterize underemployment, the unemployment rate is a questionable indicator.

Reducing the unemployment rate is one of the key objectives of public economic policy. However, as we shall see, this indicator is not without its faults: used on its own, it can be misleading.

Don’t confuse the unemployed with job seekers

The number of unemployed is estimated by national statistical institutes, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the United States or Insee in France. They base their estimates on the International Labor Organization (ILO) definition of unemployment.

An unemployed person is a person of working age (15 or over) who :

- did not work at all during the reference week;

- is available for work within 15 days and ;

- actively looked for work in the previous month.

Data are estimated from questionnaire surveys(Enquête Emploi in France; in Europe, all national surveys are grouped together in the ” EU Labour Force Survey ” published by Eurostat). The aim is to provide a standardized, non-manipulable assessment, enabling comparisons over time and between different countries.

The number of jobseekers is also often reported in the press or by governments. They are produced by the government bodies that receive, compensate and guide jobseekers, such as Pôle Emploi in France. These figures correspond to the number of people registered with these organizations: they are therefore not comparable over time or between countries, as they depend on regulatory or institutional developments (who can register? how are people deregistered, etc.).

Logically, these data do not overlap with unemployment figures. For example, in France, category A 4 is close to the ILO definition of the unemployed, but does not include unregistered jobseekers (such as young graduates looking for their first job and not entitled to compensation). Conversely, some people registered with Pôle emploi may not meet all the ILO criteria (no active job search and/or unavailable within 15 days). At the end of 2017, the number of people registered with Pôle emploi in category A stood at 3.7 million, and the number of unemployed people in the ILO sense at 2.7 million. 5 .

Find out more

Where to find the figures

The unemployment rate is too narrow an indicator

Unemployment has a strong conventional component: it’s a “status”, not a “physical” reality. It is possible to be unemployed but not unemployed (e.g. student, pensioner, housewife or househusband); someone who has only worked one hour in the reference week is not considered unemployed.

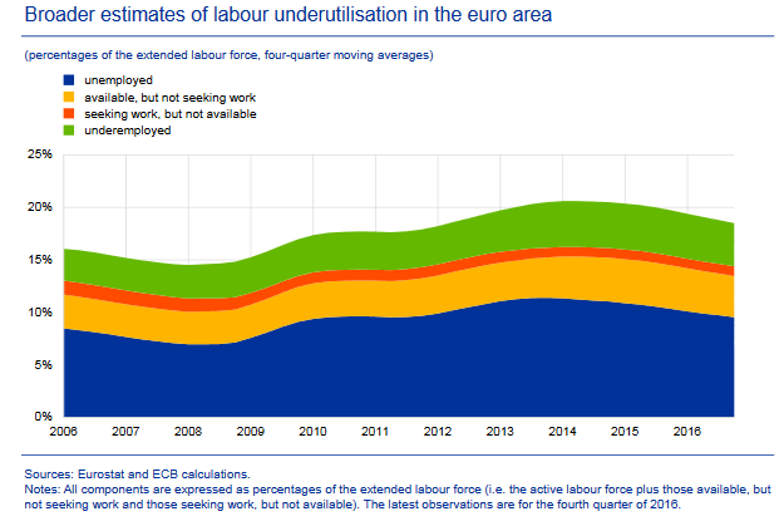

In its May 2017 Economic Bulletin, the ECB looked at “labor market slack” 6 . Noting that the fall in the unemployment rate in the eurozone has not translated into wage increases as it did in the past, the ECB highlights the fact that the unemployment rate is too narrow an indicator today to correctly assess the employment situation. It overlooks two categories of the population concerned by the phenomenon.

– The unemployment halo refers to people who are looking for work but who do not meet the other two criteria of the ILO definition: they are not available within 15 days (because they are on an internship, in training, ill, etc.) or they have not taken any steps to actively seek employment (these are the “discouraged” unemployed).

– Underemployment refers to part-timers who wish to work more (involuntary part-time).

The graph below shows that while the unemployment rate in the eurozone stood at around 9.5% of the “extended working population

7

at the end of 2016, an extended unemployment indicator (including the above-mentioned population categories) would be 18%.

Source ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3 / 2017 – Box Assessing labour market slack

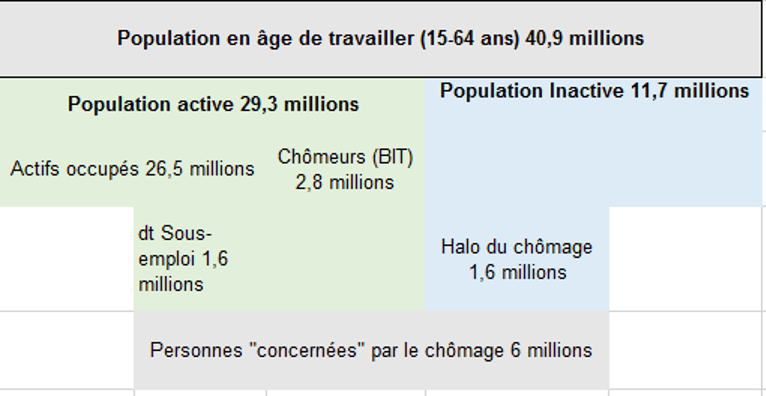

Breakdown of the French working-age population in 2017

As shown in the table below 8 in France in 2017, the number of unemployed people in the ILO sense was 2.8 million, while nearly 6 million were affected by unemployment. 9 .

Source Une photographie du marché du travail en 2017 – INSEE (rounded figures – Excluding Mayotte)

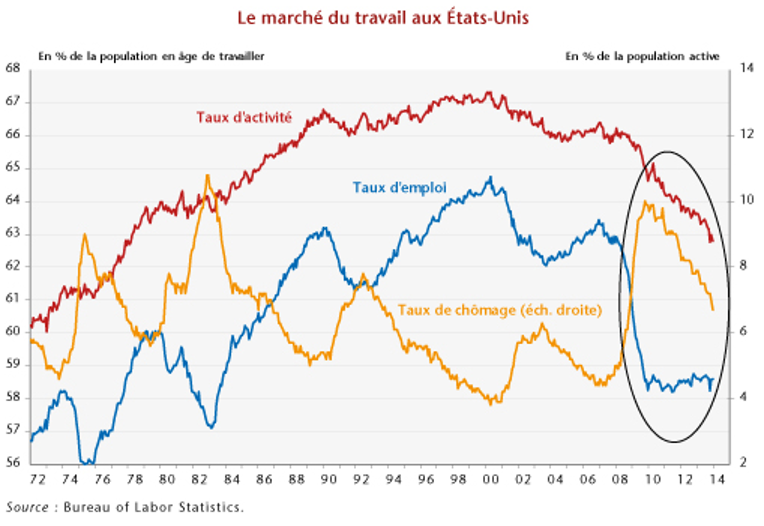

Focusing on the unemployment rate alone can lead to misinterpretations of the employment situation.

For example, in the first half of the 2010s, the rapid fall in the US unemployment rate was regularly cited as evidence of renewed growth in the United States. However, a closer look at the figures reveals that this decline has more to do with many people leaving the workforce (increasing the number of discouraged unemployed) than with job creation.

Source Christine Rifflart,“Ce que cache la baisse du taux de chômage américain”, OFCE Blog, January 17, 2014.

Another example: the fall in the unemployment rate may in fact conceal the precariousness of the labor market, with the multiplication of short-term jobs or involuntary part-time work, and incomes that are far too low to live in dignity (notion of the working poor). 10 .

The COVID 19 crisis provided another particularly striking example. Despite the impact of the containment measures on the economy, the unemployment rate in France has continued to fall, reaching around 7% at the end of June 2020. Beyond the announcement effects, we need to look at the INSEE note to understand how such results are possible. It’s also well explained in Olivier Passet’s video on Xerfi Canal.

For this reason, some authors suggest measuring a “ full-time equivalent employment (or non-employment) rate”. “employment (or non-employment) rate in full-time equivalents”. See the work of economists Guillaume Duval and Gabriel Galand.

Productivity gains have been spectacular since the start of the industrial era

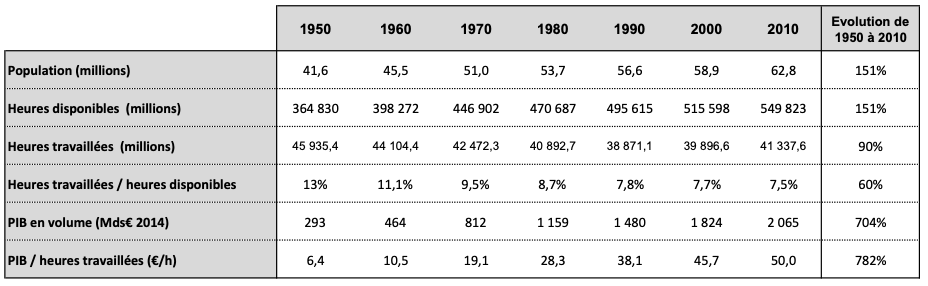

A study of long-term statistics shows the extent to which gains in labor productivity 11 since the beginning of the industrial era.

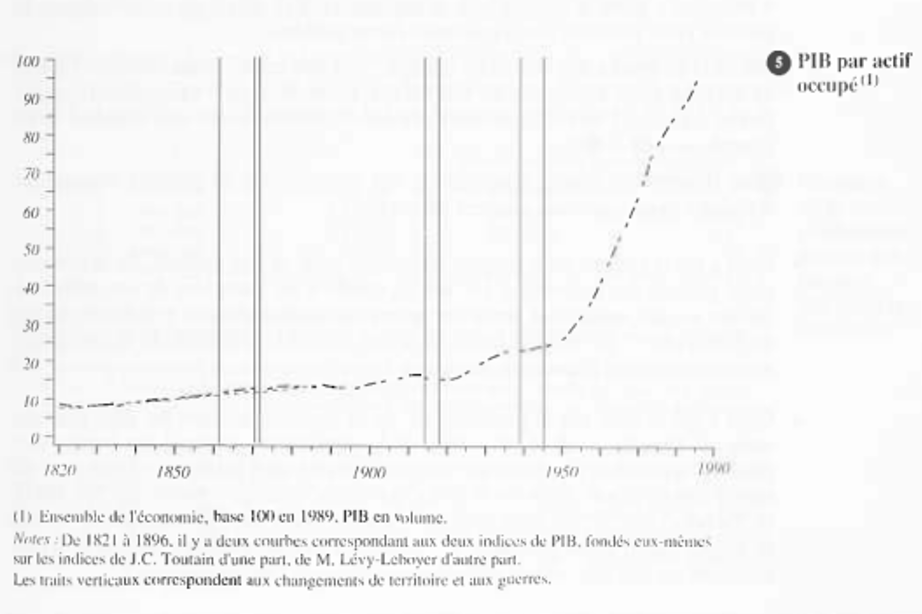

In its study Deux siècles de travail en France (Two centuries of work in France), Insee estimates that GDP per employed person in France increased by a factor of almost 13 between 1820 and 2000.

Source: Deux siècles de travail en France – Olivier Marchand and Claude Thélot – Insee – 1991 (graph 5)

The results are even more spectacular when working time is taken into account: between the beginning of the 19th century and the end of the 20th century, the average annual working time of employed persons was almost halved. 12 as a result of government-led reductions in working hours (introduction and gradual increase in paid vacations, reduction in weekly working hours) and the development of part-time working at the end of the twentieth century. 13 .

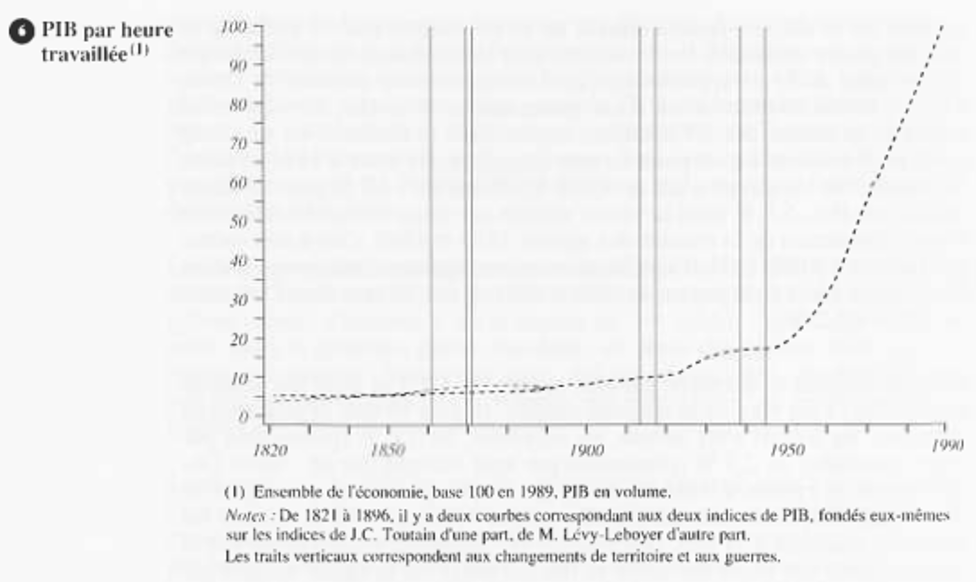

As a result, GDP per hour worked increased by a factor of almost 25!

Source Deux siècles de travail en France op.cit (graph 6)

In short, over the period 1950-2010, output per hour worked increased almost 8-fold. What’s more, productivity gains over the long term, which are already impressive when considered at the macroeconomic level, are even more so when we look at specific sectors.

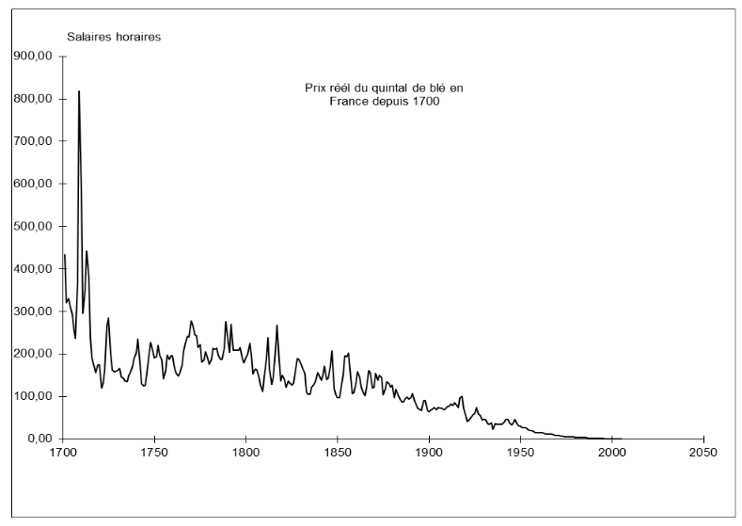

These productivity gains have enabled an extraordinary rise in living standards, the extent of which has been demonstrated by the work of French economist Jean Fourastié (1907-1990) and his successors. He set out to calculate changes in the “real price” of a good or service over the long term in France. To do this, he compares the nominal price of the product with the labor cost of the lowest-paid worker (today, this is the Smic in France). 14 . The “real price” of a product, at a given date and in a given country, thus represents in this work an estimate of the working time required by the least qualified worker to acquire this product.

The following graph shows the results of these calculations in the field of agriculture, using the example of wheat in France.

Source The fall in wheat prices, the most important event in economic history over the last three centuries – Jacqueline Fourastié

Until the middle of the 19th century, the real price of a quintal of wheat fluctuated between 150 and 250 hourly wages. 15 . Today, it is 0.9: it takes less than an hour’s wage in France to buy 100kg of wheat. It’s easy to see why we’ve gone from a situation of endemic famine to one of near-abundance of food.

A few other examples

– In France, in 1925, a laborer had to work 200 hours to buy a bicycle and almost 4 hours to buy a dozen eggs; in the 2000s, he only needs to work around 20 hours to acquire the former and around 20 minutes for the latter (sources: for eggs and bicycles).

– Owning a low-end car in 1948 (2CV) required 3,000 hourly wages; today, 650 hourly wages are enough (source here). This gives a rough idea of the productivity gains made possible by the mechanization of car factories.

– In Louis XIV’s time, a 4 m2 mirror cost 4 to 5 times more than a tapestry of the same size. Making a 4 m2 mirror took 35,000 to 40,000 man-hours, compared with 6 to 7 today. Producing 4 m2 of haute lisse tapestry still requires between 8,000 and 16,000 man-hours. And the price has kept pace with the labor content: tapestry is worth 1,000 to 3,000 times more than glass. 16 .

Gains in labor productivity are mainly due to the replacement of human labor by that of machines and the energy that powers them.

For productivity gains to occur, human labor must be replaced by “something else”. According to economic theory, this “something else” is technical progress. 17 i.e. all innovations that improve the efficiency of production: product innovations (e.g. plastics), process innovations (new manufacturing methods, such as mechanization, and new ways of using energy) or organizational innovations (e.g. division of labor with Taylorism, assembly line work with Ford, just-in-time with Toyotism, etc.).

These useful distinctions, however, mask the fact that over the long term, technical progress has mainly manifested itself in the replacement of man by machine.

Take agriculture, for example.

The French agricultural workforce (family and salaried) has fallen from 6.2 million people in 1955, or 31% of total employment, to less than 900,000 today, or around 3% of the working population. The number of farms in 2016 was 436,000, compared with 2.3 million in 1955. At the same time, farm yields have risen sharply. For wheat, they have risen from less than 20 quintals per hectare in the early 1950s, to an average of 70 in 2018 (and even over 100 on many farms). 18 . This trend cannot be explained without reference to the parallel development of machinery in the fields and on farms (tractors, combine harvesters, milking machines, irrigation equipment, etc.), as well as that used to manufacture and transport seeds, pesticides and fertilizers (it should be added that the latter two inputs are manufactured using fossil fuels), and to market production.

Let’s take a closer look at organizational innovations.

Admittedly, the division of labor introduced by Taylorism did increase the productivity of individual employees. But the increase in productivity enabled by this innovation was multiplied by the use of machines, whether within the factory itself (conveyor belts on assembly lines, progressive mechanization and robotization of tasks), for the supply of raw materials or for the flow of production (mechanization of mines, development of road and sea transport). Similarly, product innovations require machines for their manufacture (and very often use oil directly as a raw material: this is the case for plastics, fertilizers, pesticides, many medicines, etc.).

This evolution is linked to the fact that the work done by machines (and the energy that powers them) is out of all proportion to that done by humans. A miner with his shovel and pickaxe extracts 100 times less ore than a site machine operator in an industrialized mine.

How many energy slaves do we have?

According to history lessons, slavery was abolished in the West under pressure from humanist movements. However, according to historian Jean-François Mouhot, without the possibility of replacing free human labor with machines capable of producing much more, and progressively “more cheaply”, the end of slavery in France would have been postponed. On his website, engineer Jean-Marc Jancovici calculates that one liter of petrol burnt in a car produces as much mechanical energy as 10 men climbing 2000 km with 30kg on their backs. He concludes that some 400 to 500 “energy slaves” would be needed if the average French person’s energy consumption were to be replaced by human labor.

Over the long term, unemployment in the broad sense of the term is mainly due to machinery and secondarily to competition from low-wage countries.

The question of the causes of unemployment is clouded by questions of terminology. We are interested here in the causes of the decline in total time worked in a “developed” country, i.e., the “shrinking of the cake” that constitutes the supply of jobs for a given working time. This shrinking of the cake has multiple consequences for work, depending on the social categories concerned, the skills of individuals, the functioning of the “labor market”, legal working hours, the institutional and economic conditions for supporting the unemployed, and so on. But this is the main issue at stake: if the supply of jobs falls, their distribution is bound to become more complicated to organize.

If you read the news, you’d think that the main cause of this drop in the job supply in Western countries is linked to relocation to low-wage countries. In this article, however, we aim to demonstrate that, at global level, the main cause of job destruction is linked to labor productivity, the replacement of man by machine. In the literature, this is referred to as the capital-labour trade-off.

Corporate accounting makes payroll 19 the employees’ share of production, as expenses to be reduced. This is a powerful incentive for business leaders to cut labor costs. At the microeconomic level 20 it is clearly in their interest to reduce this share in order to increase their margins.

There are two ways to do this:

– increase labour productivity: produce the same output using less human labour;

– reduce salaries either directly in the company (which is difficult in countries with protective labor laws) or through the company itself. 21 ) or by subcontracting or outsourcing part of production (to companies with the same productivity but lower wages) in the same country or in countries with lower wages.

Clearly, these two methods do not have the same impact on employment. In the first case, there is a reduction in the volume of work required, and therefore a drop in employment. In the second case, “expensive” work is replaced by less “expensive” work: the impact is not on the overall volume of work, but on the quality of employment.

On a country-by-country basis, competition with low-wage countries can become a source of unemployment, as companies prefer (and sometimes have no choice) to produce where it costs them the least. Globalization and the lowering of customs tariffs, often accompanied by currency dumping, mean that wages in developed countries are competing with low wages in emerging countries. Low transport costs 22 did not change the equation, many companies have relocated their activities, while others (such as the electronics industry) have set up directly in these countries. This international competition has led to an uneven distribution of jobs, with certain countries doing better in one area or another. Nonetheless, the primary cause of unemployment remains the fact that the overall volume of employment is insufficient due to mechanization.

Finally, even in low-wage countries, mechanization is gaining ground 23 because machine-generated work always ends up costing less than human labor, in those trades where substitution is possible.

Human labor still more expensive than machine and energy labor – a numerical example

As noted above, 1 liter of petrol burnt in a car produces as much mechanical energy as 10 days of intense physical work by a healthy adult male. That’s already enormous! If we add price to the equation, it becomes phenomenal. A liter of petrol costs around €1.5, compared with the labour cost of 10 people paid the minimum wage for a day (i.e. around €1,200): for the same energy released, petrol costs 800 times less than human labour.

Of course, we also need to include the cost of depreciating the car that transformed this gasoline into mechanical energy (in motion). Let’s take the example of a car costing €25,000, driving a maximum of 250,000 km over its lifetime and consuming 8 liters per 100km (i.e. 12.5km for 1 liter). The cost per liter of petrol consumed by this car is therefore the sum of the car’s depreciation, i.e. €1.25 (€25,000 / 250,000 km * 12.5km), and the €1.5 of petrol, i.e. €2.75.

That’s still 435 times less than the cost of the human labor corresponding to the mechanical energy produced by that liter of gasoline.

NB. This comparison would have to be qualified with other energies, but as oil has played a decisive role in the transformation of our economies, it remains useful in explaining it.

This theme of replacing man by machine is not new. In fact, it’s resurfacing today with the development of robotization and artificial intelligence. 24 with fears that it will replace not only physical work, but also intellectual activities (e.g. automatic translators, algorithms replacing traders, medical analysis robots, etc.).

Economists have regularly invalidated this thesis on the grounds that labor productivity is a source of economic growth, and therefore creates jobs either in new activities (e.g. those required to design and build the machines in question) or via the additional purchasing power (generated by the redistribution of productivity gains), which is a source of new demand. The jobs lost would therefore be more than offset by jobs in the same industry, thanks to market expansion, and by jobs in new industries. 25 . However, while these mechanisms may have worked during the 30 Glorieuses, there’s nothing automatic about them (see Myth 2 for the redistribution of productivity gains).

The quest for productivity gains can have negative social and ecological consequences

Beyond its effect on employment volumes, the priority given to gains in labor productivity can have other negative effects on society, particularly in a context where the economy needs to adapt to the physical and ecological realities of our planet.

The quest for productivity gains can be particularly destructive in the service sector. The concept of productivity gains only makes sense if we can dissociate the quantity produced from the volume of work required to produce it. However, in many so-called “relational” services, there is no quantifiable product other than the time spent looking after beneficiaries who require care, advice, training, live shows, listening… It is therefore virtually impossible to measure physical productivity (i.e., working time in relation to the quantity produced). It is, however, possible to measure productivity in terms of value (i.e. the quantity of work in relation to the added value generated by the activity). Since we don’t (yet) know how to replace a doctor, teacher or lawyer with a machine, labor productivity in the service sector is limited to the ability to organize “better”. This is why productivity gains have been much lower in services than in industry or agriculture. The quest for labor productivity leads to a systematic undermining of working conditions and the quality of services rendered. 26 . Productivity means fewer nursing staff to carry out a greater number of procedures, fewer supervisors for children in nurseries and schools, care for the elderly reduced to the strict minimum, less time devoted by social workers to the people they deal with… We apply a logic of industrial performance and cost-cutting that threatens the individual quality and social usefulness of the services provided, since these are largely based on human relations.

Furthermore, the quest for gains in labor productivity is a major obstacle to the necessary shift towards a more sustainable economy. Indeed, most production processes that consume fewer natural resources (energy, water, soil, biomass, etc.) and pollute less require more labor than the same polluting, resource-exploiting production processes. Many jobs in sustainable agriculture, for example, are undoubtedly less productive (in terms of manpower), even if they are better paid and more efficient when all the factors of production used are taken into account (including those now forgotten, i.e. natural resources and the planet’s capacity to absorb our waste and pollution).

Sharing work can create jobs, as was the case when the 35-hour week was introduced in France.

Over the long term, effective working time (as a percentage of the human lifespan) has steadily decreased, as the statistics for France show. So, in effect, we’ve been sharing the work. The 35-hour working week introduced under Lionel Jospin also helped to create jobs (an Insee study put the figure at 350,000). 27 and a censured DARES report 28 confirmed these figures). The extent of the debate at the time was due, in part, to the fact that the changeover was sometimes carried out too quickly (as in the case of hospitals, where there was a shortage of staff). And for company directors and employers’ representatives, the switchover was complicated to implement.

The condition of “workers” (in terms of employment rates and income levels) depends primarily on the overall macroeconomic situation.

It was the economist William Phillips (1914-1975) who first attempted to formalize a relationship that seems fairly obvious: at a given moment (and all other things being equal, in particular legal labor laws and working hours), it is the balance of power on the labor market that determines wages and the number of jobs. If the supply of jobs is higher than demand (i.e., if there is a shortage of manpower, or a “seller’s market”, as opposed to a “buyer’s market” situation where it is the buyers of labor – the employers – who impose their conditions), it is likely that wages will rise, and that we will approach full employment. Conversely, if companies (public or private) and government agencies offer few jobs to a labor force in search of work, wages are likely to fall and unemployment to stagnate or rise.

This tension can clearly be observed in sub-sections of the “labor market”; today, for example, demand for IT specialists is high, and so are their salaries.

On a global level, the statistical proof of these causal links is more difficult to demonstrate, and has been the subject of much debate. Given the poor quality of the unemployment rate to represent the situation of workers in precarious situations, it seems to us that the statistical difficulty remains unresolved. The ECB recognized this when it observed that the unemployment rate camouflaged a much worse employment situation 29 . The labor market (in Europe) is therefore more of a “buyer” than the unemployment rate suggests.

William Phillips’ initial idea (to show the inverse correlation between unemployment and labor costs) was transformed into a discussion of the inflation/unemployment trade-off: a situation of full employment would result in inflation (with wage rises being transmitted into generalized price rises). Conversely, inflation could only be controlled at the cost of minimum unemployment.

Milton Friedman, the theorist of the Chicago School, introduced the concept of ” natural unemployment ” in 1968; New Keynesian economists introduced the concept of NAIRU (non-inflation accelerating unemployment rate) in 1968. 30 ) in 1975. These concepts (natural unemployment and NAIRU) are tragic in the primary sense of the word: they suggest that the public authorities can do nothing about unemployment other than reduce it, albeit a little, at the cost of a resumption of inflation, clearly unwanted by the upper middle classes and pensioners…

However, it is quite clear that :

- a situation of strong growth, such as that of the Thirty Glorious, and as experienced by emerging countries, creates work and drives up the price of labor;

- a public stimulus can boost activity and thus help create jobs, at least in the sectors concerned.

But if we reason in a no-growth or very low-growth world, it’s just as clear that productivity gains, if not shared, create downward pressure on wages and upward pressure on unemployment.

Unemployment is seen as a burden on the community, whereas it is a potential source of wealth.

Unemployment is seen and managed as a burden on the community. The unemployed weigh on the cost prices of companies (which participate in the financing of unemployment insurance when it exists). 31 ) and on public budgets. The “global cost of unemployment” in France is estimated at 100 billion euros per year by economist Jean Gadrey. 32 . In international competition, this mechanism is unfavorable to companies in the most “generous” countries. The temptation is therefore great to reduce it, and then to justify these restrictions with moral or microeconomic arguments: paying the unemployed to do nothing encourages laziness, is unfair to those who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow, and so on.

If we stop looking at things from an accounting angle, it’s clear that the unemployed represent available energy, latent creativity, which would be very useful for developing many of the activities expected of the population, particularly with a view to the ecological transition, which could lead to less use of machines in certain cases, to limit the use of fossil fuels. There’s no shortage of money or useful projects. Numerous solutions and experiments exist: subsidized employment, public-sector jobs, increased public procurement in transitional sectors, experimentation with zero unemployment, support for transitional companies, etc.

Seen in this light, unemployment is a real saving, since it frees up forces from immediate production that are potentially available to…do or produce something else. Unemployment is therefore a sign of great wealth. 33 of our societies. In France today, we have saved an amount of available time that can be estimated at 200 days x 3 million = 600 million man-days (considering only the unemployed in the strict sense). A considerable amount of savings which should be considered… but which we do nothing with.

Failing to mobilize these “idle” savings collectively is both a huge waste and a major political risk: too many people in an “inactivity trap” – possibly “from father to son” – are not inclined to trust governments and their promises.

Preconceived notions

Unemployment linked only to labor market rigidities

According to today’s “dominant theory”, the labor market is “naturally in equilibrium”. In other words, any worker looking for a job should find one, provided he or she can be paid at a “fair price” (i.e., according to this theory, at the level of his or her contribution to the company’s performance, known as “marginal labor productivity”). However, there are many obstacles preventing the labor market from achieving this “natural” equilibrium.

In 1994, theOECD’s employment survey, on which its employment strategy is based, clearly reflects this thinking: ” to achieve social objectives, policies have been pursued which have had the unintended consequence of accentuating the rigidity of markets, including essentially labor markets “. The study lists all the rigidities that have since been systematically used as arguments to justify labor market flexibilization policies.

- Introduction of a minimum wage 34 by limiting the fall in wages, would prevent an adjustment between supply and demand for labor, and cause unemployment.

- The difficulty of laying people off and the excessive severance payments are said to deter employers from hiring.

- The regulatory reduction in working hours would prevent an increase in “working time flexibility” (the development of part-time work).

- The responsibility lies with the unemployed themselves, who are said to have inadequate skills or to be taking advantage of overly generous unemployment benefits or minimum social benefits to do nothing (see misconceptions 3 and 4).

Since then, policies to make the labor market more flexible have become a priority for reducing unemployment. The OECD regularly publishes indicators on employment protection and studies emphasizing the importance of labor market flexibility. 35 without any systematic evaluation of the impact of these policies. This is also the position expressed very simply by Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the ECB, in 2007: “Rigidity pays for itself in additional unemployment”.

According to this view, public policy should focus on tackling these various rigidities. This is what France has been doing for several quinquennia, without convincing results.

This is what was done in Germany with the Hartz laws. We now know that their main effect was to lead to the spread of the “working poor”. The German miracle of the early 2000s has nothing to do with these laws. It can be explained very differently.

The “German miracle” of the 2000s

In 2000, when German industry entered the euro at an overvalued Deutschemark rate, it realized that it was uncompetitive and took steps to remedy the situation. It began to relocate to Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and at the same time succeeded in convincing the unions to moderate wage increases. This is the result of threats of relocation or rationalization that are perceived as highly credible. 36 .

In 2003-2004, as the economy failed to take off and Germany remained mired in high unemployment and a persistent federal deficit, the Schroeder government decided to help its industry by reforming the labor market. These were the Hartz 1 to 4 reforms. But these reforms only marginally helped industry, which in fact lacked demand. On the other hand, they did help to reduce unemployment, mainly by creating large numbers of poor and/or precarious workers, especially in the service sector.

At the same time, growth in emerging countries, led by China, was rising sharply, creating explosive demand for industrial capital goods and cars, Germany’s specialties.

In other words, if the Hartz reforms had not been implemented, the German miracle would still have taken place, with a smaller, but socially better, drop in unemployment.

Since the 2008 crisis, other factors have enabled Germany to continue its economic domination of Europe:

– a massive drop in interest rates linked to “Safe Harbor” (the fact that German government debt offered investors such a capital guarantee that it could be financed at negative interest rates), which was a boon for both the government and German firms;

– the euro’s fall against the dollar (from 1.6 in 2008), which has made it possible to compensate outside the euro zone for exports lost within the zone as a result of the austerity policies implemented in many countries;

-the persistent absence (despite the Hartz laws) of “flexibility” in the labor market, which meant they didn’t lay anyone off in 2008 despite a recession twice as deep as France’s, resulting in buoyant domestic demand and a rapid recovery in exports.

Finally, let’s not forget that the argument of labor market flexibility is not new. If we take a step back in history, we realize that the aim of many social struggles has been to regulate working conditions, and precisely to guarantee a level of contractual security for employees that runs counter to the flexibility sometimes sought by management.

Rising productivity would be the main source of GDP growth, and therefore of employment.

If there’s one apparently intangible “dogma”, it’s that productivity (or technical progress) is the source of growth, and growth the solution to unemployment.

The reality is quite different. Admittedly, in a world without technical progress, production is by definition limited by the available labor force (and its mechanical extension, considered intangible). At best, it is a function of demographic growth. As we saw above, productivity gains (resulting from technical progress) translate directly into a reduction in the quantity of labor required to produce a given output. This is their very definition.

This frees up labor forces that can be used to produce more or something else, and thus become a source of economic growth. This has been the case for most of the industrial era, but there’s nothing automatic about it.

For production to grow, it is necessary that at the macroeconomic level :

– companies decide to increase production by investing more in capacity than they already have 37 or by creating new activities;

– additional production can be sold. The purchasing power potentially freed up by productivity gains must therefore be sufficiently distributed to future buyers (via wage increases or price cuts).

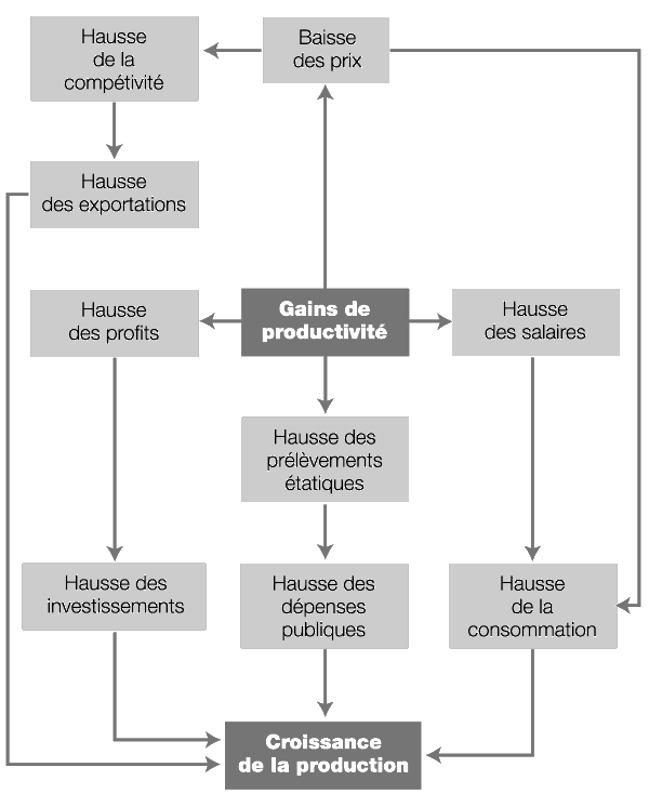

There’s nothing spontaneous about this last point: numerous biases can prevent the redistribution of productivity gains from being sufficient to enable production to flow. The diagram below illustrates three ways in which the redistribution of productivity gains can boost output.

Source From J.M. Albertini, E. Coiffier, M. Guiot, Pourquoi le chômage ? Scodel 1987 – diagram online here

However, these paths are not automatic. Productivity gains can be diverted from economic activity. Company directors and shareholders receive part of the income distributed by the sale of production, but as they are often among the highest earners, they have a high propensity to save (and savings are not necessarily transformed into investment in companies, quite the contrary). The State can increase compulsory levies to reimburse the interest on the debt, and so on.

In order to sell off all production, some buyers have to resort to credit. Credit is therefore at least as much a source of growth as productivity gains.

On the question of employment, let’s reiterate that the first effect of technical progress is to deprive the person being replaced by a machine of work. For this job loss to be more than compensated for at the collective level, growth is needed. 38 . This is one of the reasons why production growth is still widely considered vital, despite the many studies denouncing its negative effects. In a world of weak or even stagnant growth, as is currently the case, it is clear that if productivity continues to rise (thanks to robotization or artificial intelligence), unemployment and job insecurity (involuntary part-time work and other precarious activities) can only increase, unless we organize a reduction in working hours.

Productivity is not the enemy of employment

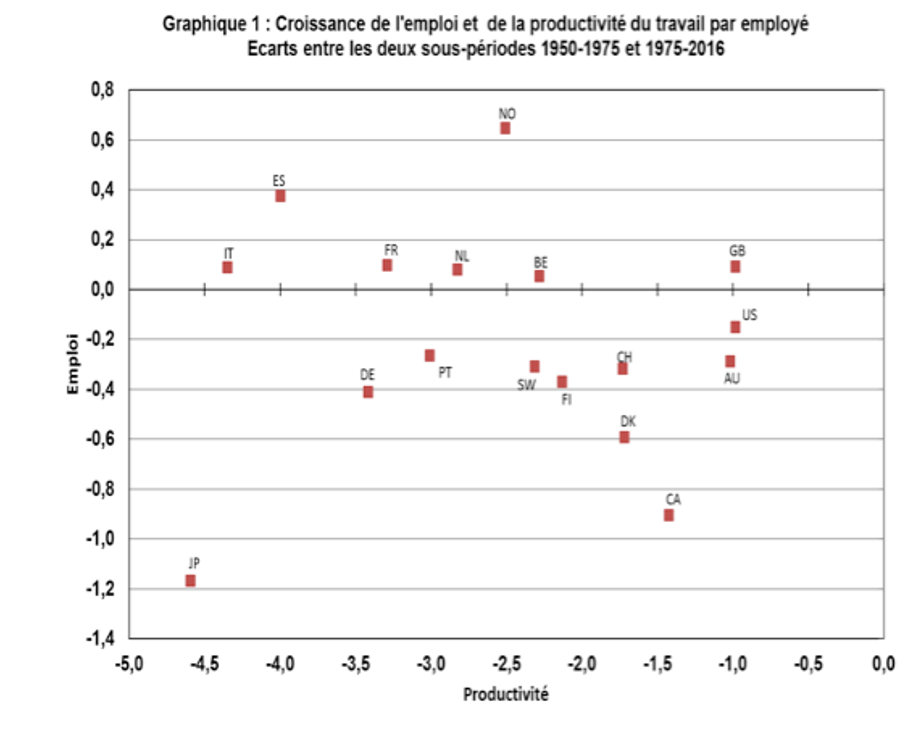

We’ll start here with a well-presented argument by economist Gilbert Cette 39 and reproduce a graph summarizing it. In a nutshell, by comparing the evolution of productivity and employment over two periods (1950-1975) and (1975-2016) for a series of countries, it appears that the slowdown in productivity is not favorable to employment in the medium term, which means, on the contrary, that productivity is not the enemy of employment.

Source Bergeaud, Cette and Lecat, Le Bel Avenir de la croissance, Odile Jacob, 2018, http://longtermproductivity.com/

It’s easy to see why this line of reasoning leads to a different conclusion from ours. If the working time content of the jobs considered changes, it goes without saying that the evolution of productivity cannot be read into it. In other words, since unemployment and employment are conventional evolutionary statistical constructs, whereas productivity is a “physical” measure, it is logical that correlations between these two types of data cannot provide easily interpretable information.

Unemployment is the choice of the unemployed (unfilled jobs)

This idea came to the fore again when the President of the French Republic explained to a young person that all he had to do to find a job was cross the street. It doesn’t stand up to the most elementary analysis.

In a December 2017 issue, Pôle emploi reports that out of 3.2 million offers submitted, 2.9 million were filled, half of them in less than 38 days. That’s 300,000 unfilled jobs, but only 150,000 correspond to genuine vacancies (97,000 offers were cancelled due to the disappearance of the need or lack of budget and 53,000 concerned recruitment still in progress) 40 .

In any case, it’s clear that if these jobs were to be filled, it would only slightly alter the weight of unemployment (which, as we saw in Truth 1, in 2017 concerned almost 2.5 million people in the narrow sense and 6 million in the broad sense), which is therefore due to other causes. Moreover, the fact that jobs are unfilled can also be the result of anomalies in the supply (underpaid or very arduous jobs, “unstable” supply, etc.). In short, the unemployed are not the cause of unemployment…

More apprenticeships, technical training and continuing education would be enough to reduce unemployment.

This preconceived idea (often evoked for young people, whose unemployment rate is particularly worrying) doesn’t stand up to analysis any more than the previous one, and for similar reasons. If unemployment were due to a lack or defect in training, we’d be seeing a large number of unsatisfied job offers, which is not the case, as we’ve just seen. Improving training (initial or continuing) both in terms of content and matching with business needs is certainly desirable, but it can only have a marginal effect on the unemployment rate. For the “best trained”, the effect will be to improve their ability to find a job in what will always be intense competition, if nothing else changes.

Priority should be given to facilitating the development of “competitive” jobs

In the neo-liberal view of the economy, full employment is the automatic result of an unfettered, unconstrained market. In this vision, _free and undistorted_ international competition is a good thing, because it forces governments to free up this functioning so that companies can maintain or even increase their competitiveness. Consequently, the priority of public policy must be to reduce barriers and rigidities to the ideal functioning of the labor market. Full employment would necessarily follow, and any jobs destroyed by civil servants or subsidized employment would immediately be recreated in the market sphere, and more jobs would be created until full employment is reached.

Before returning to the theoretical argument, it’s worth mentioning this statistical data, provided by Michel Berry 41 :

” Basic income in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques is made up of 20% productive activities, 20% public wages, 40% residents’ income and 20% social assistance. Four-fifths do not depend on the productive economy, the orders of magnitude being the same in non-metropolitan territories. 42 “.

Clearly, considering 80% of jobs in the region to be of no interest could, in practice, lead to a number of errors of judgement in public policy…

To return to the theoretical argument, it suffices to note that general equilibrium models, which lead to the conclusion that full employment would be achieved provided the labor market functions without hindrance, represent an abstract world, with no link to reality (starting with the representation of the behavior of the economic agent) to deduce that their conclusions cannot precisely concern economic and social reality. From this we can deduce the falsity of the preconceived notion highlighted in this paragraph.

Civil servants and subsidized jobs would burden companies, preventing them from creating “real” jobs.

An analysis of public services shows that the jobs concerned are, of course, real jobs: whether in health, education, security, environmental protection… or in national or regional administrative functions. And it shows that it is unfounded to consider that they are more costly than their equivalent in the private sector.

However, it is indisputable that the compulsory levies imposed on companies increase their cost price, and, all other things being equal, limit their capacity to invest and create jobs.

However, nothing can be concluded from this observation. It is by no means clear that a company seeing its costs fall (via a reduction in public or subsidized jobs, which would therefore lead to a reduction in compulsory deductions) would automatically be led to create jobs: this is not its vocation a priori, in today’s economic world; it would certainly see its profits increase, but would have to make a trade-off between dividend distribution, wage increases, hiring or investment with a view to higher future profits.

Nor is it obvious that in sectors neglected by the public sector (health or education, for example), the private sector would create more jobs than those destroyed by the privatization of public services. The reasoning behind this type of measure – the supposedly higher economic performance of the private sector – would rather lead to the opposite conclusion.

Unemployment is inevitable

The persistence of unemployment raises doubts as to whether it can really be eradicated. Examples of apparent success (such as in the USA, where the unemployment rate fell sharply in the 2010s) are not conclusive, as not all the jobs created are sufficiently well-paid or of good quality. Therefore, the best that can be done is to “limit the damage” (i.e. to make social transfers “in favor” of the unemployed, to limit poverty).

This fatalism is in fact based on a priority given to economic life, to which all other issues are subordinated. The priority is to produce ever more material wealth, and the best system for achieving this is unfettered global competition. Business competitiveness is the priority, whatever the cost in human, social and ecological terms.

This raises the question of whether we shouldn’t turn the argument on its head. It’s clear that unemployment, the fear of lack (of food or housing, but also of work), and the fear of being downgraded are favorable to company managers when it comes to negotiating wages and even working conditions as a whole. Those who work can be asked to work harder, to be more competitive and cheaper. Otherwise, they’ll join the ranks of the unemployed.

If we are to overcome this inevitability, we need to reverse our values. We need to put economic competition at the service of an ecological and solidarity-based project, rather than making social and ecological issues conditional on economic competition.

- It is and well represented in France by the book by Pierre Cahuc, André Zylberberg, Les ennemis de l’emploi – le chômage, fatalité ou nécessité? Flammarion, 2015. ↩︎

- See for example the summary by Alexandra Roulet, Améliorer les appariements sur le marché du travail, Paris, Les Presses de Sciences Po, coll. “Sécuriser l’emploi”, 2018, 112 p. ↩︎

- Although the last famine in the West occurred in Ireland in 1851, it has not yet been completely eradicated worldwide, and could increase again due to pressure on natural resources. Moreover, malnutrition still affects almost 800 million people, not because of insufficient food production, but because of problems linked to economic imbalances or political contexts. ↩︎

- Pôle Emploi nomenclature : ↩︎

- To find out more: INSEE note de conjoncture June 2016 – chapter “Comparaison sur la période récente entre l’évolution du chômage au sens du BIT et celle du nombre de demandeurs d’emploi en fin de mois inscrits à Pôle emploi”, p.81-84) ↩︎

- ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3 / 2017 – Assessing labor market slack. In this report, we read that the OECD and the USA are making greater use of this broader indicator: “The US Bureau of Labor Statistics refers to this measure as the “U6” indicator. Even broader measures are under investigation. See, for example, Hornstein, A., Kudlyak, M. and Lange, F., Measuring resource utilization in the labor market, Economic Quarterly, Vol.100(1), Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 2014.” ↩︎

- The extended active population includes the active population + people available for work but not actively looking for work in the previous month + people looking for work but not available within 15 days. ↩︎

- This table is an updated version of the one produced by Luc Semana in his excellent article Chômage: brève histoire d’un concept(May 2018 – Site des SES de l’ENS de Lyon). ↩︎

- Note that Pôle Emploi’s figures show the same type of bias, rising from 3.7 million people at the end of 2017 for category A, which is the most widely used in the media, to 5.9 million when categories B and C are added. ↩︎

- A case in point is the zero-hour contract, which has developed in the European Union, as well as in the UK and France (vacation contracts at universities or “task-based” contracts for home proofreaders in the publishing industry, for example). The main feature of this type of contract is that the employer does not specify any minimum working hours or duration. The employee is paid only for the hours worked, and must be available at any time of the day. In 2015, in the UK, there were around 1.5 million contracts with a few hours per month, and a further 1.3 million with no hours worked at all. More than one in ten employers in the country make use of them. ↩︎

- Labor productivity refers to the ratio between the output produced (measured in physical quantity _ number of cars manufactured, for example_ or in value _ value added is used here) and the labor required to achieve it (measured either in number of hours or number of jobs). ↩︎

- from around 3040 hours a year in 1830 to 1650 hours in 1989 (see table 8 p190 of Deux siècles de travail en France op.cit. ↩︎

- see for example the review article L’évolution de la durée du travail en France depuis 1950, Anne Châteauneuf-Malclès (2017) ↩︎

- Find out more about the method used in the document Presentation of price statistics. Price theory according to Jean Fourastié (2013) ↩︎

- In 1709, the date of the last famine in France, the real price of a quintal of wheat soared to 817 hourly wages (due to a harsh winter that froze the harvest). At this price, the lowest-paid workers had to work a long day to bring home 1-2kg of wheat for their families. ↩︎

- See Jean Fourastié’s article Pourquoi tant de tapisseries et une seule galerie des glaces à Versailles? and Jacqueline Fourastié, Le progrès technique a-il encore une influence sur la vie économique? Sociétal – N° 50 -2005 ↩︎

- Technical progress may not lead to productivity gains. This is Solow’s paradox when he talks about computer-related productivity gains, which can be seen everywhere except in the statistics. ↩︎

- Sources: For 1955 figures – L’agriculture française depuis cinquante ans : des petites exploitations familiales aux droits à paiement unique – Maurice Desriers – INSEE références – 2017 and for current statistics Graphagri 2019 ↩︎

- And the associated payroll and employer charges. ↩︎

- At the macro-economic level (as expressed and translated into action by Henri Ford), employees are the customers of companies; their purchasing power must be sufficient to buy the products sold (contrary to Say’s law, according to which the purchasing power created by companies is equal to their production). However, this macro-economic reasoning is generally not taken into account by company managers, who are driven by the economic performance of their companies, not by overall economic performance. ↩︎

- It should be noted that the development of mass unemployment and international competition between nations have resulted in regular attacks on this protection and in wage stagnation. The so-called new-generation bilateral treaties aim precisely to limit the constraints of labor law, on the grounds of “investment protection”. ↩︎

- In this respect, it should be noted that the phenomenon of relocation has also been made possible by mechanization and the growing use of fossil fuels: the transport of goods by boat, train or truck has increased exponentially in recent decades. ↩︎

- See Verisk Maplecroft’s Human Rights Outlook 2018 and articles commenting on this study Robotization risks increasing slavery in Southeast Asia – Novethic July 2018. ↩︎

- See for example: The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne – WP Oxford University, 2013. The future of jobs – World Economic Forum report – 2018. ↩︎

- This is the thesis developed by Alfred Sauvy in La machine et le chômage, Paris, Dunod, 1980. ↩︎

- This logic, which undermines quality, is pushed to the limit in public services, where it is not possible to calculate labor productivity in terms of value (since these services have no sales and generate no added value). Instead, we simply compare working time with the cost of production, i.e. mainly with wages! See, for example, the Report of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Stiglitz, Sen, Fitoussi 2009. ↩︎

- Alain Gubian, Stéphane Jugnot, Frédéric Lerais and Vladimir Passeron, ” Les effets de la RTT sur l’emploi : des estimations ex ante aux évaluations ex post “, INSEE Économie et statistique, nos 376-377, 2004. ↩︎

- Many commentators have emphasized how difficult it was to understand the censure of this report, which was intended to assess the effects of a law of the Republic, other than the fact that its conclusions did not suit the government in power. See for example 35 heures : ce que dit le rapport secret de l’IGAS, Le Monde – 2016. Les inspecteurs de l’Igas réhabilitent les 35 heures, Mediapart, 2016. 35 heures : le rapport non publié qui fait polémique, Les Echos, 2016. . The unpublished version of the report can be downloaded here. ↩︎

- See ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 3 / 2017 – Box Assessing labour market slack. This example is developed in Truth 1 ↩︎

- Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU) ↩︎

- We’ll come back to this later (see the accounting chapter), but every company director knows that his or her cost price must include salaries and ALL social charges, whatever the semantics used. In concrete terms, in France, an SME paying a net salary of 100 euros must disburse around 180 euros, adding to this salary all “social charges”. This average varies according to salary level. ↩︎

- See the article Le coût public du chômage: plus de 100 milliards d’euros par an? (2016). This is a global cost that includes direct and indirect public spending (unemployment benefits; spending on reintegration or support schemes; administrative costs of the organizations responsible for these benefits) as well as lost earnings for public administrations, in terms of lost social security contributions and direct and indirect taxes. ↩︎

- Although they had very few resources, medieval societies were able to extract from ordinary production the resources needed to build cathedrals. So, in a society of “scarcity”, it was possible to do grandiose and apparently “free” things (in the sense that they made no money). ↩︎

- In a recent article, Alan Manning, professor at the London School of Economics, shows that the consensus on the minimum wage has reversed, moving from its questioning to its almost generalized defense. The Elusive Employment Effect of the Minimum Wage – Alan Manning CEP Discussion Paper No 1428 – May 2016 ↩︎

- See, for example, OECD Employment Outlook 2013 – Chapter 2 Protecting jobs, enhancing flexibility: a new look at employment protection legislation . ↩︎

- Christian Odendahl ” The Hartz myth: a closer look at Germany’s labour market reforms “, Center for European Reform – 2017 ↩︎

- Replacing 10 workers with one machine leads to productivity gains, but does not increase production. To increase output, you either need to use those 10 workers for something else, or invest in another machine to supplement the workers. ↩︎

- Note that growth is not a sufficient condition: GDP can grow without creating jobs. See the article What if growth didn’t create jobs? Michel Husson, 2010 ↩︎

- Productivity is not the enemy of employment – Gilbert Cette -Telos 2018 ↩︎

- Statistiques et Eudes – Offres pourvues et abandons de recrutement – Pôle Emploi – December 2017. In addition to this survey, quarterly job vacancy statistics can be consulted on the Ministry of Labor website (figures from the Acemo survey, Activité et conditions d’emploi de la main-d’œuvre). These statistics concern the whole of France, but only companies with more than 10 employees. ↩︎

- Michel Berry, What if no one was perceived as useless anymore? Nouvelle revue de psychosociologie 2019/2 (N°28), Page 225-235 ↩︎

- Source: Davezies, L. 2002. “Le développement local revisité”, Paris, École de Paris du management. ↩︎