This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

Economic life is based on five main categories of economic agents: households, public administrations, commercial and financial companies and social economy structures. 1 . Companies play an economic role 2 that of producing most of the goods and services that households and public authorities purchase for consumption or investment. To do this, companies employ workers, buy intermediate goods and services from each other, and use public services provided by government agencies. They consume energy and other natural resources, and have an impact on nature.

We’ll see inEssentials 1 that the notion of enterprise is a socio-economic concept distinct from that of company, which is a legal one. This is why we mainly use this term in this module: it is this economic and social dimension that interests us in this module. What’s more, most of our discussion focuses on private companies of a certain size (and relatively little on sole proprietorships).

We’re going to take a look at the usefulness and limitations of business, and respond to some of the most common misconceptions. Are companies part of the problem or part of the solution to the ecological crisis? Are the efforts made in this area real and sufficient, or are they merely a matter of communication or greenwashing? 3 ? Should their legal form and/or governance be transformed so that they make a greater contribution to solving the ecological crisis? These questions are much more acute today than they were 30 years ago, as several planetary limits have been exceeded.

This module is closely linked to the The company and its accounting module, to which reference will be made implicitly or explicitly.

The essentials

What is a company?

The notion of the company, the central object of criticism of capitalism, is more complex than the image conveyed by the media debate on controversial multinationals.

In reality, the nature and longevity of companies are different. 4 and of very different sizes: from the sole proprietorship, to the multinational operating in many different countries and sectors, to the multi-century-old company. They operate in a wide range of regulatory and competitive environments, and have extremely varied modes of governance (e.g. from the highly regulated profession of notary to the highly competitive world of IT services). Their governance, which we discuss in Essentiel 4, can also cover very different situations.

To form an opinion on the current role and responsibility of the company in the ecological crisis and its eventual resolution, it is necessary to clearly define what we are talking about. It is also important to understand that, depending on the players involved, representations and expectations will not be the same.

Depending on the people or stakeholders involved, the company’s perception varies greatly.

For its founders, the company is a means of earning money, practicing a trade and being one’s own boss. It can also be a risky human adventure, a way of turning a dream or an idea into reality. For them, it can be a question of personal fulfillment and social success.

For non-founding managers (or for founders after a few years), the motivations may be a little different: the desire to win a market, to eliminate a competitor, to impose a new product/service, to make the share price soar, to serve a specific shareholder to increase his or her power, and so on.

For the company’s employees, the motivations can be as varied as the way in which the company is viewed. Historically, work has been seen as an inevitability: you have to work to “earn a living”.

Today, motivations can be more complex: being part of a team of friendly colleagues, the pleasure of selling for a salesperson, the need for recognition, the feeling of participating in the company’s project, its “mission” (even if this term is sometimes connoted) and the feeling of participating fully, to the extent of one’s abilities. In return, a salary (and more generally remuneration) is of course expected. The desired level of salary may be based more on considerations of fairness (obtaining a salary equivalent to that of another “comparable” person doing an equivalent job) than on the desire for an ever-higher salary. It all depends on the culture and motivations of the employee in question.

For many stakeholders and observers, a company is first and foremost a social body, a group of people who interact within a collective subject to rules of various kinds: law (company law, labor law, etc.), social customs linked to the country concerned, the company’s organization and specific management methods, the atmosphere resulting from employee interactions and initiatives…

In the region(s) where the company is based, it is seen as a provider of direct and indirect employment, by generating or stimulating activity, whether through local suppliers and service providers, or through the activities that develop to bring goods and services to its employees. It can also be perceived as a source of nuisance (particularly noise and pollution).

For financiers and some managers, the company is simply a set of assets that generate income, with varying degrees of risk, and can be valued over the long term by partial or total disposal. This vision is close to that of the economists who developed the agency theory, according to which the company is a set of contracts (see Idea 2).

For some observers and activists, particularly those who claim to be followers of Marxism and its successors, the company is a place of confrontation between capital and labor, one subordinating the other by definition.

Depending on the vision of the company one adopts, questions of governance and revenue sharing arise and are resolved quite differently, even within the same legal framework.

The company as seen by various scientific disciplines

The various scientific disciplines view the company in terms of their specialization. Mobilizing these different types of representations can help us to understand the factors that block the taking into account of “planetary limits” in corporate strategy and decision-making; these blocks are not necessarily of the order of economic rationality.

Without going into an exhaustive list, let’s take a look at a few examples.

In the field of economics, numerous theories of the firm have been developed. 5

One of the most influential today is that developed by Milton Friedman and the promoters of agency theory, for whom the firm is seen both as a set of contracts and as the property of its shareholders. Institutional economists, on the other hand, see the firm as a social construct and a collective governed by explicit or implicit rules, a point of view we adopt here.

From a sociological and anthropological perspective, the company is seen as a place of alliances, relationships and cooperation, as well as – and above all – of conflict, internal and external warfare. The company is a weapon in the “global economic war” (replacing the battalions of yesteryear): company directors are the “generals” of capitalism.

In a biological approach, the company must have a raison d’être. The terms often used in this register are of the order of life and death: the soul of the company, its DNA, its ecosystem… If it loses this sense, the company is in danger. In this vision, the founder(s) and the seed they planted transcend the company’s history. They are both driving forces and constraints: it will be difficult for successors to implement mutations that go beyond this initial “matrix”.

From a psychological point of view, a company is a theater (and sometimes a place of psychological purging) that stages egos (sometimes inordinate), desires (for enrichment, power, recognition, fulfillment), drives, values, passions, flaws (ranging from lack of certain key skills to sometimes psycho-pathological profiles) from those of the founder(s) to those of all its contributors.

In this conception, the apparent rationality of the company (decisions based on performance and efficiency criteria for its growth) is relatively weak compared to the psychic rationalities of those who create, compose and manage it.

The company as seen by official statistics

Public statistics bodies, such as Insee in France, collect and analyze company data to build up a picture of the country’s productive structure and its evolution over time, and to compare it with that of other countries.

The image of the company and the production system conveyed by these bodies is therefore profoundly structuring, as it serves as the basis for public debate on the subject. That’s why we’ve set out here to understand what we’re talking about.

The company as a socio-economic reality

But how do you define the outline of a company? This is not as trivial a question as it might seem. The answer will vary according to the size and complexity of the organization concerned.

At first glance, one might think that a company is defined by its legal existence. Indeed, for a long time it was confused with the “legal unit” (see box below).

Such a definition, however, is restrictive and poorly reflects economic reality.

As Insee explains, “many legal units are not autonomous: they belong to a larger whole, which groups together several units and which holds decision-making power, notably over the allocation of production factors or research and development”. It is this whole that we call a company, and which makes economic sense. 6

Finally, a company is also a work collective, a social body. This is why the notion of “enterprise” is often found in the French Labor Code, where the term is interpreted as a group of workers carrying out a common activity under the authority of a single employer.

Definitions – Establishments, legal units, companies

An establishment is a unit of production of goods and services (market or not) located geographically on a given territory (e.g.: a bakery, a warehouse, a farm, an industrial production site, an “office” of a consulting firm). It is legally dependent on a legal unit. See Insee and Eurostat definition.

A legal unit (UL) is a legal entity under public or private law (company, sole proprietorship, administration, local authority, association, etc.). 7 It may be a legal entity or a natural person (a self-employed person, for example). It may have one or more establishments (e.g. a chain of bakeries, supermarkets, etc.). In 2020, 95% of ULs in France will be single-establishment. See the Insee and Eurosta t.

A group is a set of companies (one of the legal forms ULs can take) linked together by legal and/or financial ties and controlled by the group head. A group is said to be multinational when at least two of its constituent companies are located in different countries. See the definition .

“The “enterprise” is the smallest combination of legal units that constitutes an organizational unit for the production of goods and services, enjoying a certain degree of decision-making autonomy, notably for the allocation of its current resources.”

Insee 8 See Eurostat definition.

A company can therefore be an independent legal unit or a group. In France, all ULs and their establishments are identified in the SIRENE register.

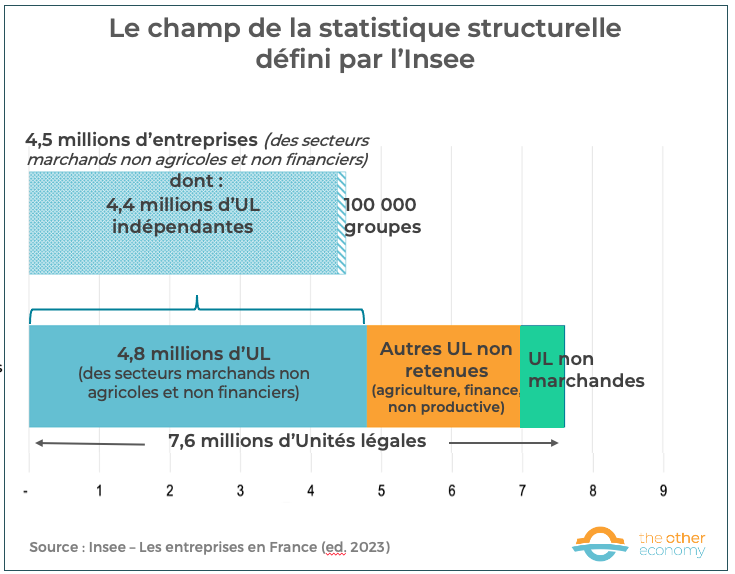

Source Les différents niveaux et champs d’observation de l’appareil productif en France – Les entreprises en France Édition 2023 – Insee

How many companies in France?

To analyze the production system, we need to focus on the commercial sector, and have access to consistent, harmonized accounting data.

Insee has thus defined the scope of structural business statistics (also known as the “non-agricultural, non-financial market sectors”), from which the following are excluded:

- the agricultural (except forestry) and financial (except holding companies and financial and insurance auxiliaries) sectors, as their accounting is not homogeneous with the other sectors.

- non-market activities (carried out by public administrations or associations).

- non-productive activities

In France, there are 4.5 million businesses in the non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors (2021).

Source Les différents niveaux et champs d’observation de l’appareil productif en France – Les entreprises en France Édition 2023 – Insee and L’essentiel sur… les entreprises – Insee 2024

Companies are not necessarily corporations

When we talk about a company, we often equate it with a corporation. Yet the two concepts are quite different.

As we saw in the previous section, a company is a socio-economic reality whose legal basis is one or more legal units.

The company is one of the forms that a legal entity can take, but it is not the only one (see definition below). Sole proprietorships are also very numerous. It’s important to understand this, as debates about business often focus on corporations, with their specific governance structures (power and value sharing) and objectives.

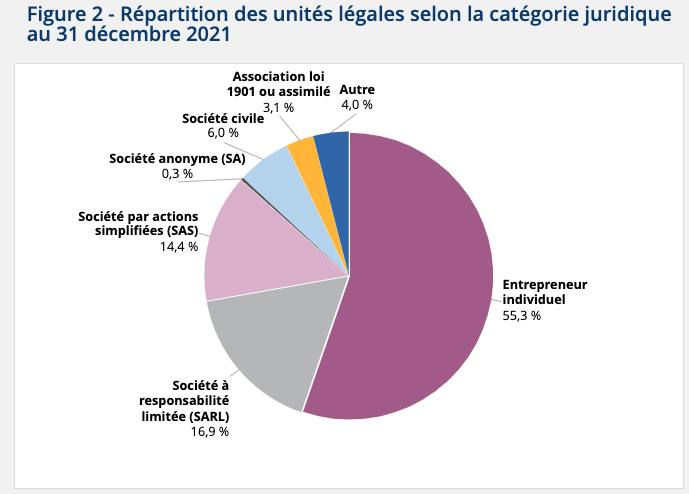

While INSEE unfortunately does not make public information on the legal categories of the 4.8 million legal units (and a fortiori companies) included in the scope of structural business statistics, we can nevertheless draw some orders of magnitude from the data on all 7.6 million legal units.

Breakdown of legal units in France by legal category at the end of 2021

At the end of 2021, of the 7.6 million legal units in France, over 55% are sole proprietorships (approx. 4.2 million), 37.6% are companies (approx. 2.8 million) and 3% are associations (approx. 236,000). The “Other” category includes in particular public administrations (state administration, local authorities, social security administrations, etc.).

Source Les différents niveaux et champs d’observation de l’appareil productif en France – Les entreprises en France Édition 2023 – Insee

The scope of structural business statistics essentially covers sole traders and companies. However, some sole traders and companies belong to the agricultural and financial sectors and are therefore excluded. Others may have no productive activity at all. 9 Some non-trading companies have no commercial activity. 10 Some structures listed under “Other”, such as such as public enterprises, may be included.

It is therefore not possible to fully deduce from the above statistics the legal form of the companies included in Insee’s structural statistics. However, we can assume that at least one out of every two businesses is a sole trader.

The differences between legal forms

- Sole proprietorships

These are companies created in their own name: they have no legal personality separate from their founder. Until very recently, sole traders were liable for company debts on their own assets (apart from their main residence). Since the law in favor of independent professional activity of 2022, only the elements necessary for their professional activity can be seized in the event of professional default.

Among individual entrepreneurs, there is a specific status: that of micro-entrepreneur (called auto-entrepreneur until 2014), which offers streamlined business start-up formalities and simplified calculation and payment of social security contributions and income tax.

- The companies

The notion of company is defined in article 1832 of the French Civil Code.

“A company is formed by two or more persons who agree by contract to allocate property or their industry to a joint venture, with a view to sharing the profits or benefiting from any savings that may result. In the cases provided for by law, it may be set up by an act of will by a single person. The associates undertake to contribute to any losses.

A company is therefore a legal entity resulting from a legal act whose primary objective is to make profits for those who created it. 11

There are many different types of company, which can be grouped into two broad categories with different implications for their founders:

Partnerships are characterized by the importance of the collaboration of the partners who have created (or joined) the company. In return for the resources they contribute to form the company’s capital, they receive financial securities known as shares, the transfer of which is subject to strict controls. 12 (unlike shares). This is one way of preventing capital dilution. Partners are jointly and severally liable for the company’s debts. This means that one partner can be sued for another’s debt, and that partners are liable on all their personal (and not just professional) assets. Trust between partners is therefore essential.

The legal forms of partnership in France are the société en nom collectif (SNC), the société en participation and above all the civil partnership These include the SCI (société civile immobilière) for property management, and the SCP (société civile professionnelle) for regulated professions (notaries, lawyers, auditors, doctors, etc.).

The joint-stock companies are more focused on the securities issued than on the partners themselves. The initial contributions to form the capital take the form of financial securities, shares, which the associates (or shareholders) are free to issue. 13 (including on a stock exchange, if the company is listed). Moreover, the liability of associates is limited to their contribution, and they are not jointly and severally liable.

The main forms of joint-stock company in France are the SA (société anonyme) and the SAS (société anonyme simplifiée). SARLs are considered mixed or hybrid companies. 14

This initial overview shows that a company is not necessarily a corporation, although the two terms are often confused. The former is a socio-economic concept used to analyze the production system, while the latter is a legal status with very specific characteristics.

Companies come in all sizes, ages and weights in productive activity

Statistics on companies are extremely rich. For example, they enable us to understand their enormous diversity, whether in terms of size, sector of activity or impact on the productive system. However, as we often point out in The Other Economy, we also need to take a step back from the figures to understand the values behind the different ways of counting.

The production structure is highly concentrated

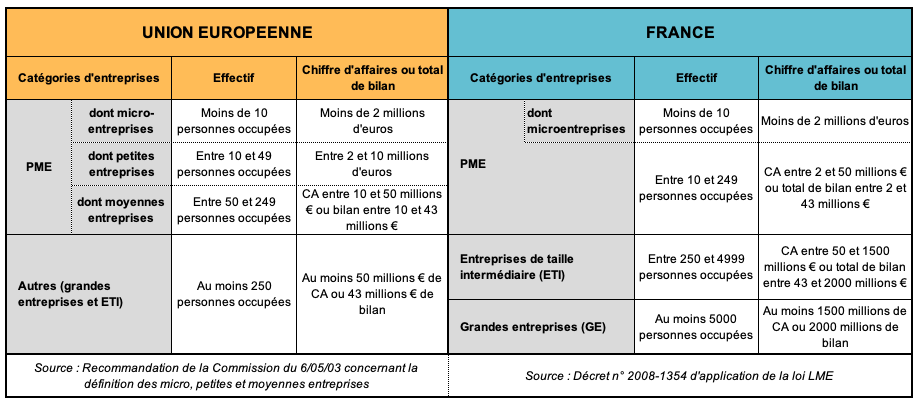

A common way of observing the world of companies is to differentiate them by size, in order to assess their weight in the productive fabric in terms of various indicators (number, employment, sales, added value, exports, etc.). Thresholds have been defined for this purpose since 2003 at European Union level (member states are required to respect maximum thresholds, with some leeway).

Thresholds for classifying companies by size in the European Union and France

The main differences between the two classifications lie in the fact that the European Union has created more subdivisions within SMEs, while France has chosen to distinguish between ETIs and large companies.

Source In a 2003 Recommendation, the European Commission defined thresholds for categorizing companies according to headcount and financial data (sales or balance sheet total). France transposed the Commission’s recommendations in a decree implementing the 2008 Law on the Modernization of the Economy.

Be careful not to confuse the microenterprise (MIC) referred to here, which is a statistical concept and can take the legal form of a sole proprietorship or a company, with the status of microentrepreneur (discussed inEssentiel 1.4), which is a specific status of sole proprietorship in France.

The workforce corresponds to the number of “persons employed”. It includes company employees and non-employees (owner-managers, highly invested partners, persons treated as employees under national law). 15

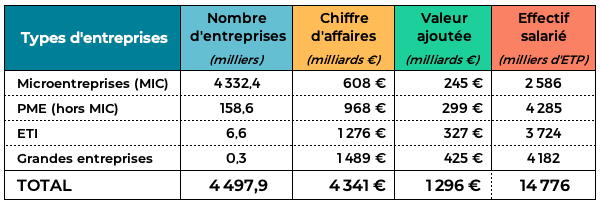

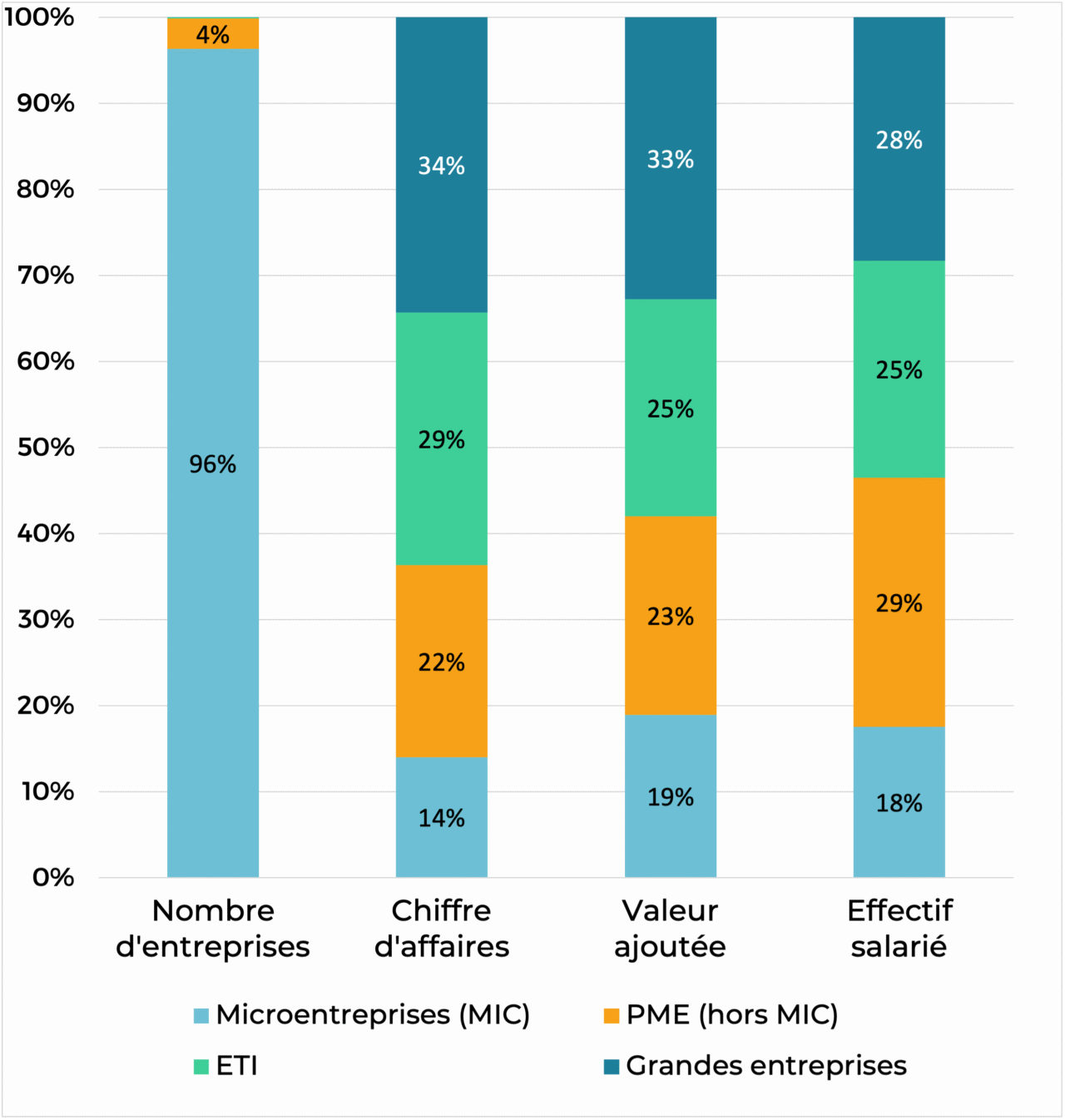

Some indicators of France’s production structure by company size

In 2021, the 4.5 million companies in France’s non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors will generate 1,296 billion euros in added value and employ 14.7 million full-time equivalent (FTE) workers, bringing the total number of jobs in France to around 30 million.

Source L’appareil productif français en 2021– Les entreprises en France Édition 2023 – Insee

Scope: non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors. For a definition, see Essential 1.3 How many companies in France?

As can be seen from the graph below, France’s productive fabric is highly concentrated. While small and medium-sized businesses will account for 96% of companies (4.3 million) in 2021, their weighting is much lower in terms of number of employees (18%) and added value (19%). Conversely, the 300 or so large companies account for 28% of employees and 33% of added value.

France’s production base is highly concentrated (2021)

Source L’appareil productif français en 2021– Les entreprises en France Édition 2023 – Insee

Scope: non-agricultural, non-financial market sectors (for definition, see Essentiel 1.3 How many companies in France?).

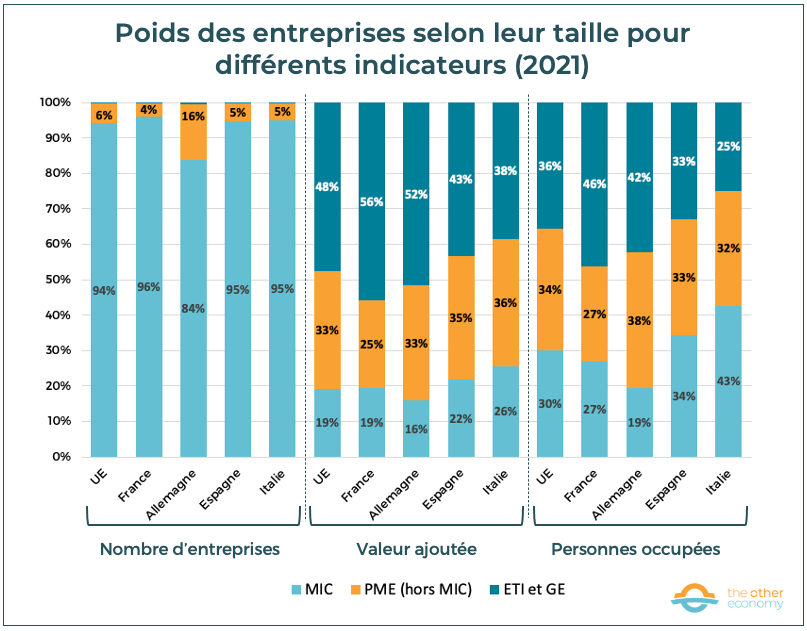

The French situation is not exceptional in Europe. Everywhere, MICs dominate in terms of number of companies. ETIs and large companies generate around half of added value. In terms of employment, the situation is more contrasted: TMCs account for just under a third of the workforce in the European Union, but only 19% in Germany and 43% in Italy.

Comparison of production structure in different European Union countries by company size

Source Eurostat – Company statistics by NACE Rev. 2 size class and activity (consulted in June 2024)

Scope: industry, construction and market services (this scope is roughly equivalent to that of the non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors used by INSEE).

Please note that the employment indicator used is the number of people employed. 15 (the headcount indicator), whereas Insee uses the FTE employee indicator (not all employees are salaried).

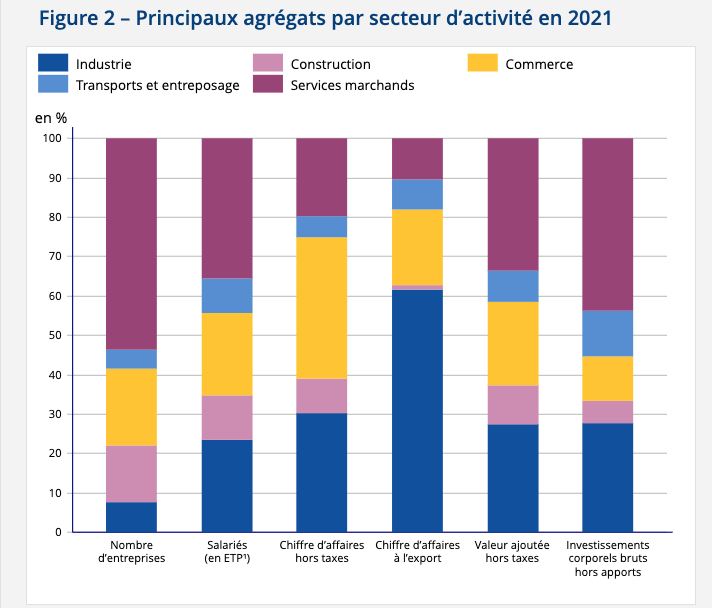

Other types of information available: sectors, company demographics, etc.

Statistical institutes provide a wide range of other data for analyzing the productive fabric. For example, it is possible to analyze the weight of different economic sectors in terms of sales, added value, employment, investment, exports, etc.

Main aggregates by business sector in 2021

Source Mainly non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors – Companies in France 2023 Edition – Insee

It should be noted that the mainly non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors include 3.7 million companies with sales of 4142 billion. They therefore constitute a sub-section 17 of the structural statistics field used by Insee (which we defined inEssentiel 1), which comprises 4.5 billion companies with sales of 4241 billion.

There are also statistics on the “demography” of businesses, because they don’t last forever. For example, in France, 61% of companies created in 2014 were still active five years after their creation. 18 . This means that 40% of companies “die” within 5 years of their creation. 19 .

Find out more

Each year, Insee produces a comprehensive publication on Companies in France.

For the European Union, the Eurostat statistics explained website offers a comprehensive section.

The need to step back from statistical data

As is often the case in The Other Economy, we’d like to emphasize the importance of taking a step back from statistics. Although they are based on concrete data collected from economic players, they are nevertheless subject to conventions, i.e. choices made by statisticians according to reasoning and justifications that cannot be totally objective in terms of describing reality.

The scope observed by statistical bodies is not neutral

Insee’s Les entreprises en France – Édition 2023report is intended to provide “a comprehensive structural view of our production system”.

As we saw inEssential 1.3, structural business statistics cover the “non-agricultural and non-financial market sectors”, which in 2021 comprised 4.5 million businesses, corresponding to 4.8 million legal units.

Insee, however, lists nearly 7.6 million active legal units in France. The transition from one figure to another has involved making choices, adopting conventions justified by technical considerations (exclusion of most agricultural and financial structures, as their accounting systems differ from those of other sectors) or without justification (exclusion of non-market activities).

However, given that our ambition is to analyze the productive system, the exclusion of agricultural production, financial services and all non-market activities raises questions. Are public services such as education, health, justice and policing not considered to be part of productive activity? And what about the contribution of hundreds of thousands of associations? These are legitimate questions, as these choices send out a biased message about what makes up a country’s productive fabric.

It is interesting to compare the figures for the production system defined by INSEE with those for the economy as a whole.

Non-market production, for example, will account for just over 11% of total French production in 2021. 20 and that’s without counting all the services that are not subject to any monetary transaction (for example, the work of France’s 12 million volunteers).

Value added amounted to 2,217 billion euros. 21 that same year. With 1,296 billion euros of added value, the French production system as defined by INSEE represents less than 60%. The same type of analysis is enlightening when it comes to employment (see Misconception 1 : only companies create wealth and jobs).

Of course, the agricultural, financial, non-profit and public administration sectors are also subject to statistical analysis. But the angle is not the same. In the case of government agencies, for example, the question of public finances (expenditure, debt and deficit) is given much greater prominence than that of their contribution to the productive system. This issue is also well illustrated by the social and solidarity economy (SSE), which lies at the interface between the market and non-market sectors, due to the multiplicity of structures that make it up. Although statistics on this subject are still sketchy, it is clear that this part of the economy, which focuses more on social purpose than profit, accounts for a substantial proportion of activity, particularly in terms of employment (see Essentiel 4 on governance).

Slowly evolving statistical conventions were not designed to capture the material dimension of production.

Statistical conventions are usually drawn up within a regional (European Union) or even international framework. They correspond to the needs of the time, and take a long time to evolve.

The example of the sectoral division of the economy is illuminating in this respect. Created in 1993, the NAF (nomenclature d’activités françaises) is “a nomenclature of productive economic activities, primarily designed to facilitate the organization of economic and social information”. It has the same structure as the European activity nomenclature (NAVE Rev2), itself derived from the international nomenclature. It has been revised twice, in 2003 and 2008.

Developed at a time when ecological issues were barely present in public debate, this nomenclature did not take into account the consumption of natural resources and pollution linked to economic activities. Other nomenclatures were therefore developed to deal with these issues, such as the one that structures the major sectors of the economy to account for the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The correspondence between the two, and therefore the analysis of the production system in terms of these emissions, is not obvious.

The company: a place of cooperation and tension between multiple internal and external players

Companies are part of an institutional, human and natural environment

A company cannot function, let alone grow, without multiple tasks of different kinds being carried out, internally by employees or externally by service providers or suppliers.

It also depends on free or paying public services and the availability of infrastructures (transport, energy, waste, telecoms) and quality institutions (education and training, health, justice, legal system, etc.). It is embedded in human (stakeholders) and/or natural (environment) “ecosystems”.

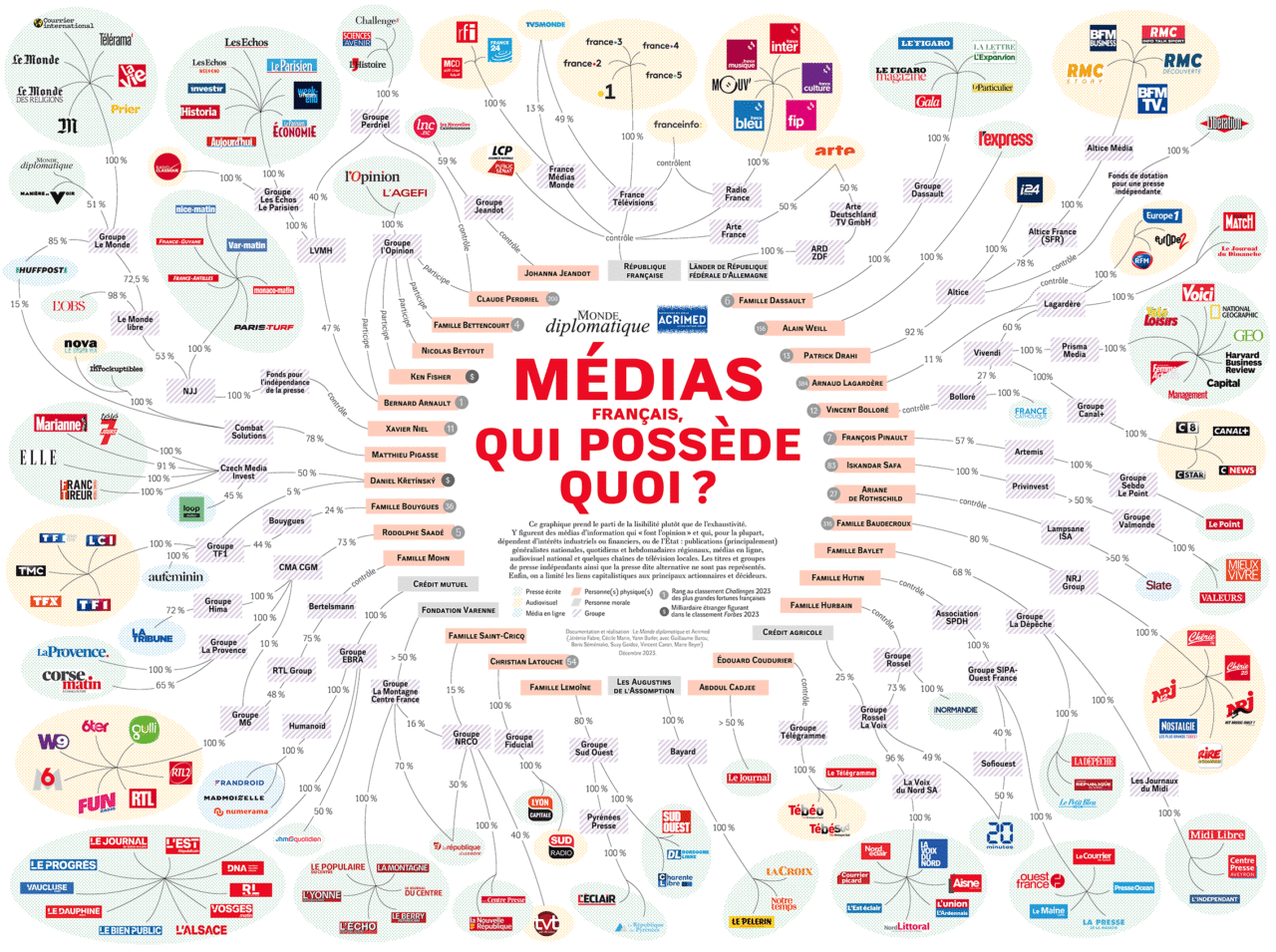

It is subject to numerous legal obligations: labor law, corporate and tax law, environmental law, business (or contract) law, intellectual property law and competition law. There are also certain sectors that are subject to specific regulations (e.g. in France: banking, insurance, bookshops, the press, etc.) and regulated professions that are subject to specific obligations. 22 ).

Lastly, we remind you that certain activities are prohibited or even criminalized. 23 . They are not necessarily economically anecdotal, and some of them are included in the GDP (see our module GDP, Growth and Planetary Resources – Sub-section How are the limits of production defined?)

Different functions are implemented in the company

The “company manager” (one person or several partners) embodies and defends the company’s project in the eyes of its customers, employees and other stakeholders. He or she is also the conductor of an orchestra, ensuring that the functions to be carried out are carried out “adequately” (i.e. at the required level of quality for an appropriate cost), and that the company fits into the ecosystem(s) with which it interacts. It is an arbiter of the many conflicts that the company experiences. So he’s not just a manager, an accountant or a director.

Let’s take a quick look at what it takes to make a business work.

A company, whatever its size, carries out a wide range of functions in-house, or has them carried out by suppliers or service providers. The number of staff assigned to each function depends not only on the size of the company, but also on its “mission” and business model.

What is a business model?

The expression business model 24 refers to the way in which a company is expected to make a profit. The most common business model is obviously the production and sale of margin-generating products or services. But there are others. The “free” press, for example, is a specific business model, in which advertising is the main source of revenue, creating biases in the choice, production and presentation of information. Another example is that of certain digital giants such as Google, which offer free services to their users and derive most of their revenue from the sale of targeted advertising based on the exploitation of these same users’ personal data.

The business model, like strategy, is a crucial aspect in the success or failure of a company. History shows us a large number of failures or successes strongly linked to the business model. The print media, with its recurrent economic difficulties, is an emblematic example.

Financiers (bankers, investors) need to understand the business model(s) of the companies in which they invest, and their sensitivity to external or internal factors. A lack of understanding of what drives a company’s profits is indeed very risky.

Source To find out more, see the video Understanding business models in 5 minutes on Xerfi Canal.

Here is a brief list of the functions performed within the company, and embodied in different ways depending on the case:

- defining the “mission” and the strategy for the more or less long term;

- sales (marketing, advertising, sales department, customer relations, business development) ;

- external and internal communication (with or without the press and news media) ;

- Human resources and social management: payroll, social declarations, occupational medicine, relations with staff representatives, recruitment, training, early skills management, sickness management, leave and departures (resignations, individual and collective redundancies);

- production (and supporting services), subcontracting and purchasing;

- IT management (software and hardware) ;

- accounting and financial management: company financing (credit, shareholders, markets), cash management, accounting, management control, communication and financial reporting

- legal: labor law, corporate and tax law, environmental law,

- business (or contract) law, intellectual property and competition law, etc.

- fundamental or applied research and the development of new products and services;

- public relations: relations with political and administrative authorities at the relevant level, professional organizations, NGOs, and the possibility of influencing these players;

- monitoring and controlling the company’s social and environmental responsibility.

The company is not isolated

It is part of a network of stakeholders: customers, employees, suppliers, government and public authorities, shareholders, investors, bankers. It operates in one or more territories, has neighbors and benefits from public services and infrastructures.

Businesses cannot live and develop without the implicit approval of the public, the so-called “social license to operate”; they must have a certain legitimacy that is not reduced to respect for the law, nor to the fact that they can find solvent customers. This social pressure is exerted on managers and imposes de facto limits on them.

On a more prosaic level, companies need to inspire long-term customer confidence in the quality of their products and services, and in their ability to live up to the claims they make. Increasingly, they are being questioned on their social and environmental practices.

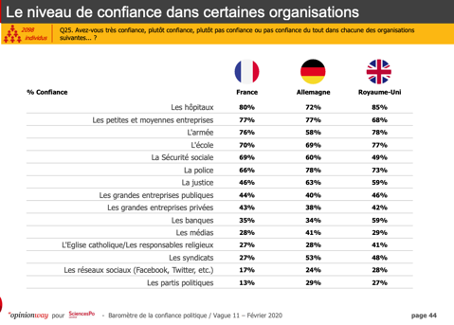

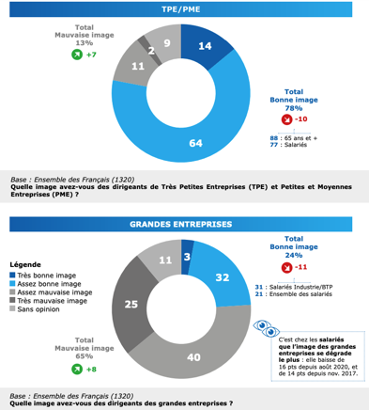

As the following extract from wave 11 of the Political Confidence Barometer (2020) shows, large private companies often inspire only lukewarm confidence.

In France, a Pinocchio prize was created to denounce “greenwashing”. Online applications such as MoralScore evaluate companies according to various criteria (environment, social contribution, privacy, working conditions, etc.). Students are increasingly reticent about, and even reject, certain large companies and groups, which is reflected in growing recruitment difficulties.

As can be seen in the barometer below, managers of large companies tend to have a poor image with the public, unlike managers of SMEs.

Source Baromètre de la relation des Français à l’Entreprise – An Elabe survey for the Institut de l’Entreprise – Edition 2023

The company, a crossroads of cooperation and conflict

The company is first and foremost a place for cooperation – that’s its raison d’être.

If a company is created, it’s because its creator(s) believe that the pooling of skills and financial capital they imagine will be more effective than their individual actions, even if organized by contracts.

Within the company, cooperation is effective, necessary and encouraged by the very principle of organization. Relationships between employees are not generally the subject of precise contracts, and everyone has room to manoeuvre. Even if individual interests are by no means absent, the company stimulates cross-services: you can do me this favor, but you have to do me that favor…

The company is also a place of conflict and tension:

- between the “boss” and the employees, the former having to embody the interests of the company (and sometimes of the capital owners), sometimes to the detriment of certain employees;

- between the company and its suppliers/service providers, where each has opposing interests (suppliers want to sell as well as possible to their customer (the company), who wants to buy as well as possible…);

- between employees, where the limits of cooperation can be revealed when it comes to pay rises, bonuses, promotions and power.

The art of management (thousands of books, seminars and training courses are sold worldwide on this subject) is precisely that of encouraging cooperation without annihilating emulation, initiative and the recognition of those who contribute most and best to the company achieving its objectives. It is also the art of arbitrating the inevitable conflicts that arise within the company.

Trade unions and employee representatives

In most cases, the company is run by the representatives of its shareholders (seeEssentiel 4 on the different forms of corporate governance). 25 ). Employees are represented in and around companies by structures charged with defending their interests, taking part in certain negotiations and, where necessary, engaging in a power struggle with management. This reality has been built up over time, and did not emerge spontaneously. Moreover, these structures have varying degrees of weight and power, depending on the era and the country.

The development of trade unionism has made it possible to win social rights

Capitalism in the 19th and early 20th centuries evolved in social terms, mainly as a result of conflicts over social rights.

The 1880s marked the birth of trade unionism in Europe, in a period marked by the notion of class struggle (between proletariat and employers). It developed on large industrial sites, where human labor was progressively fragmented to increase productivity, then increasingly mechanized, automated and finally robotized. By engaging in a power struggle with governments, notably through strikes, the unions helped achieve social progress and improved working conditions.

Milestones in social progress in France

- 1841: Ban on child labor for children under 8.

- 1864: Right to strike tolerated.

- 1874: Creation of the labor inspectorate.

- 1884: Waldeck-Rousseau law authorizing the creation of trade unions.

- 1892: Women’s working hours limited to 11 hours and prohibited at night.

- 1898: Liability of the company manager in the event of a workplace accident.

- 1900: Working time limited to 10 hours.

- 1906: Law introducing Sunday rest (which had been abolished in 1880).

- 1910: Workers’ pensions financed by employees, employers and the State.

- 1919: Working hours limited to 8 hours.

- 1936: Forty-hour week, paid vacations, right to organize freely, introduction of employee delegates, law on collective labor agreements.

- 1941: Introduction of the pay-as-you-go pension scheme and the minimum old-age pension.

- 1944: Creation of the general social security system in accordance with the program of the National Council of the Resistance.

- 1946: Recognition of the right to employment and the right to strike in the preamble to the constitution of the Fourth Republic (taken up in that of the Fifth Republic).

- 1950: Introduction of the guaranteed interprofessional minimum wage (SMIG), which became the interprofessional minimum growth wage (SMIC) in 1970.

- 1956, 1963: 3rd and 4th weeks of paid leave.

- 1982: 5th week of paid leave + law on the 39-hour week + Auroux laws on the right of expression and collective bargaining.

- 1983: Legal retirement age of 60.

- 1986: Creation of the Revenu minimum d’insertion.

- 1998: 35-hour week (Aubry Law)

- 1999: Universal health coverage.

Source Find out more on Wikipedia’s Social policy in France page

Union power was still very strong during the 30 Glorieuses (1945-1975), with notable differences between countries: some, particularly in Northern Europe, had much higher rates of unionization than others.

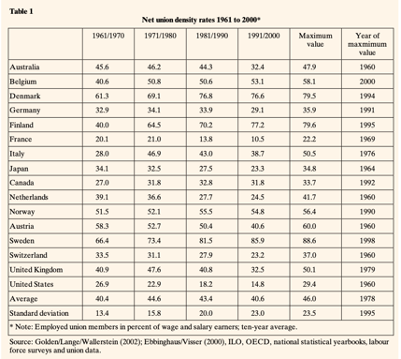

Unionization rates, 1961 – 2000

Source Trade Union Density in International, Institute for Economic Research, Munich, 2004

Share of union members among employees, 10-year average.

Over the last few decades, unionization rates have been falling almost everywhere (see OECD unionization database 2000-2020). This is particularly the case in France, where the rate plummeted from the end of the 1970s to stagnate at around 10%. 26 . In addition, a 2017 study by the Ministry of Labor’s Statistics Directorate (DARES) shows the weakening of employee participation in trade union activities, with a clear drop-off around 2010.

The causes of union decline are varied and differ from country to country:

- the decline of industrial and manufacturing activities, increasing outsourcing to large groups and the development of temporary work are all factors preventing workers from joining forces;

- cultural and ideological changes (with increasing individualization and consumerism in society, and a more general decline in militant activities);

- programmatic changes within political parties, working conditions and remuneration, and “social” legislation;

- the low representativeness of trade unions in countries like France, where they represent fewer and fewer employees.

In parallel with the development of trade unionism, social legislation has increased the role of employee representatives within the company.

In most cases, however, this role remains limited. In the French example detailed here, employee representatives have the power of expression (and not necessarily of all employees, either…), not always of consultation and even less of co-determination or co-decision.

Although the French Labor Code, which dates back to 1910, has never ceased to evolve, the Auroux laws of 1982 modified more than a third of it. These texts, comprising 2 ordinances and 4 laws, strengthened employees’ right to express their views on working conditions, endowed the works council with an operating budget, enshrined the obligation of annual collective bargaining, and created the health, safety and working conditions committee (CHSCT), as well as the right of withdrawal.

The last major reform of labor law dates back to 2017 with the Macron ordinances which, on a general level, introduced less favorable labor law for employees. These ordinances also merged the various existing representative bodies(staff delegates, CHSCT and works council) into a single body the Social and Economic Committee (CSE), mandatory in all companies with more than 11 employees.

The main role of the CSE is to present employees’ individual or collective complaints to the employer (wages, collective bargaining agreement, application of the Labor Code), and to promote good working conditions. The CSE can also investigate workplace accidents or occupational illnesses, refer matters to the labor inspectorate, and has a right of warning (in the event of infringement of personal rights or health, in situations of serious and imminent danger, as well as in matters of public health and the environment).

In companies with at least 50 employees, it must be consulted on certain issues relating to the life of the company, its strategy and employment. 27 but the employer is free to decide whether or not to take this opinion into account.

Environmental issues were a late entrant to employees’ right of expression

CHSCTs had to be convened in the event of a serious event linked to the establishment’s activity that had (or could have) harmed the environment and employees. In 2017, the creation of the CSE extended the right to alert to environmental damage.

The Climate and Resilience Act (art. 40) of 2021 expands the missions of the CSE by specifying that in companies with at least 50 employees, it ensures a collective expression of employees on the decisions of the company’s managers “particularly with regard to [their] environmental consequences” (art. L2312-8 of the French Labor Code). Lastly, the challenges of the ecological transition are included in negotiations on forward-looking management of jobs and skills (GPEC).

The challenges and variety of Governance

As we saw inEssential 1, a company is first and foremost a socio-economic reality. Its legal basis can be either a natural person (individual entrepreneur), or one (or more) legal entities (company, cooperative, mutual, etc.). We are mainly interested in legal entities here, since corporate governance implies the existence of a collective structure.

We have defined corporate governance as “a set of legal, regulatory or practical provisions that delimit the scope of the power and responsibilities of those charged with guiding the company in the long term”, on the understanding that guiding the company means “taking and controlling decisions that have a decisive effect on its sustainability and hence its lasting performance”.

We’ll see that governance involves different types of power, and that depending on the legal form of private companies, shareholders play a more or less important role.

The four powers of governance

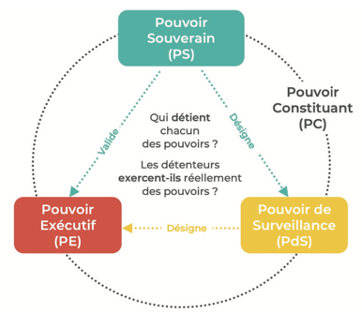

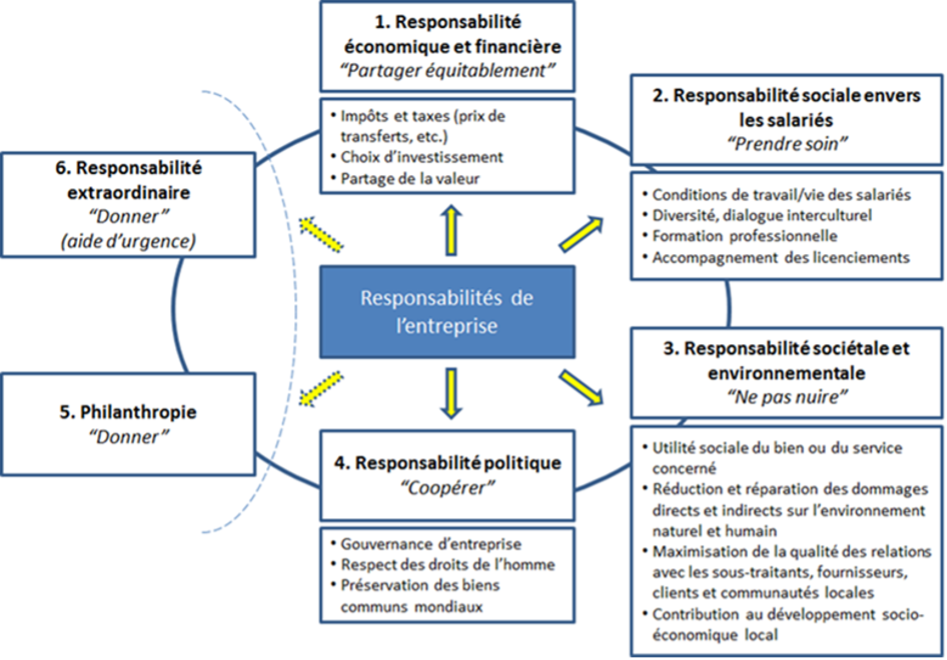

In his book, La gouvernance d’entreprise (PUF, 2018), Pierre-Yves Gomez breaks down governance-related responsibilities into four powers, which are represented in the diagram below.

This typology enables him to analyze each organizational governance according to two key questions: who holds each of these powers, formally or tacitly? How are these powers exercised by the people who hold them?

The 4 powers of corporate governance

Source Benchmark of new governance models, Heart Leadership University and Prophil (2022)

The constituent power sets all the laws and rules establishing the framework within which corporate governance can be exercised. This mainly concerns the national and international legal framework. This power is therefore mainly exercised by the public authorities, in particular the State.

Sovereign power is that which founds the others – respecting the constituent power – and ensures their continuity. It is held by shareholders in the case of companies, by members in the case of cooperatives or mutual societies, and by members in the case of associations. Its prerogatives include, in particular, validation of annual accounts, management by the executive and appointment of directors (who have supervisory powers).

The function of the supervisory board is to administer the organization, which implies, in particular, responsibility for appointing its managers (holders of executive power), selecting strategic orientations from among those proposed by them, and monitoring results. This power is exercised by the Board of Directors or the Supervisory Board.

Executive power is exercised by the organization’s manager(s). Its role is to define and implement strategy. It is accountable to the holder of sovereign power.

What is the “classic” governance of private companies?

A company is formed by two or more persons who agree by contract to allocate assets or their industry to a joint venture, with a view to sharing the profits or benefiting from any savings that may result. In the cases provided for by law, it may be instituted by the will of a single person. Partners undertake to contribute to losses.

The purpose of the company is to generate profits for its founders. For some economists, such as Milton Friedman, leader of the Chicago school of economics 28 some economists, such as Milton Friedman, leader of the Chicago School, have even made maximizing shareholder profits the company’s sole objective.

A shareholder-friendly environment

We’ll see how this objective is reflected in the concentration of power (sovereign, supervisory and sometimes executive) in the hands of shareholders. This does not mean that all companies are guided solely by the pursuit of “value creation” for shareholders, but that the general provisions make such an objective possible. This has become the largely dominant situation for large listed companies.

Sovereign power is held by the general meeting of shareholders, each of whom has generally proportional voting rights. 29 to the shares of the company’s share capital they hold (see our capital factsheet for more information). This meeting votes on the annual financial statements, validates past management and future projects, and elects the members of the Board of Directors (BOD), which holds supervisory power. 30 .

Directors have extensive powers, specified in the Articles of Association. At the very least, the Board elects its Chairman from among its members, appoints the company’s Chief Executive Officer to exercise executive power, and oversees the company’s management. In some companies, these two functions are performed by a single person, the Chairman and CEO.

This general framework can give rise to very different situations depending on how each of these powers is allocated and exercised.

For example, in a family-run business, power is often concentrated in the hands of the founder and possibly those closest to him. This is very different from a public limited company, where shareholders often have no connection with the company’s creation. Moreover, depending on the concentration of shareholders (e.g., a few large shareholders with almost all the voting rights, or at the other extreme, a very diffuse shareholder base with a multitude of small shareholders), the exercise of governance will not be the same.

In some cases, the constituent power has given employees a much greater role.

In Germany (and many other European countries), under various provisions 31 ) the “co-determination has been in place since the 1970s: employees are represented on the Board of Directors, and can account for up to 50% of members (for companies with over 2,000 employees). However, they never have a majority (the Chairman’s vote counts double), and so cannot take decisions without the agreement of at least one director representing the shareholders.

In France, in companies employing over 1,000 people, employees appoint one or two directors to represent them, with the same duties and responsibilities as shareholder representatives.

It’s important to distinguish between co-determination (where employees hold part of the supervisory power via their representatives on the Board of Directors) and employee representation bodies within the company, which usually only have consultative powers. In France, the Comité social et économique (CSE) is only consulted in certain specific cases. Moreover, the employer is not obliged to take account of the opinion given.

Governance of social economy structures

While there is no formal definition of SSE, there is a fairly broad consensus on the concept’s contours. According to the OECD, the SSE encompasses a group of organizations whose activities are “motivated by the achievement of societal objectives, by the values of solidarity, the primacy of people over capital, and, in most cases, by democratic and participative governance”. 32

In France, the legal framework laid down by the 2014 law on the social and solidarity economy captures this well. The SSE is “a mode of enterprise and economic development adapted to all areas of human activity” to which companies choose to adhere subject to compliance with several conditions:

- pursue an objective other than profit sharing ;

- democratic governance, provided for in the articles of association ;

- profits or “surpluses” are mainly used to maintain or develop the company’s business, and compulsory reserves cannot be distributed.

In simpler terms, the SSE is characterized by its focus on people and by the limitation of profit-making (for the proportion of SSE structures that are for-profit).

SSE companies are at the service of people, and emphasize this; they do not have to pay capital and are not run by representatives of funding providers.

This limited profit-making status protects SSE structures from disposals and other restructurings linked to “capital-intensive” operations (i.e. those whose main aim is to generate value for shareholders or owners of shares).

However, this also means that these structures are unable to attract massive amounts of household savings, as they do not remunerate either the risk, the deprivation of the immediate use of the money invested, or the opportunity cost (the gain linked to alternative investment options).33

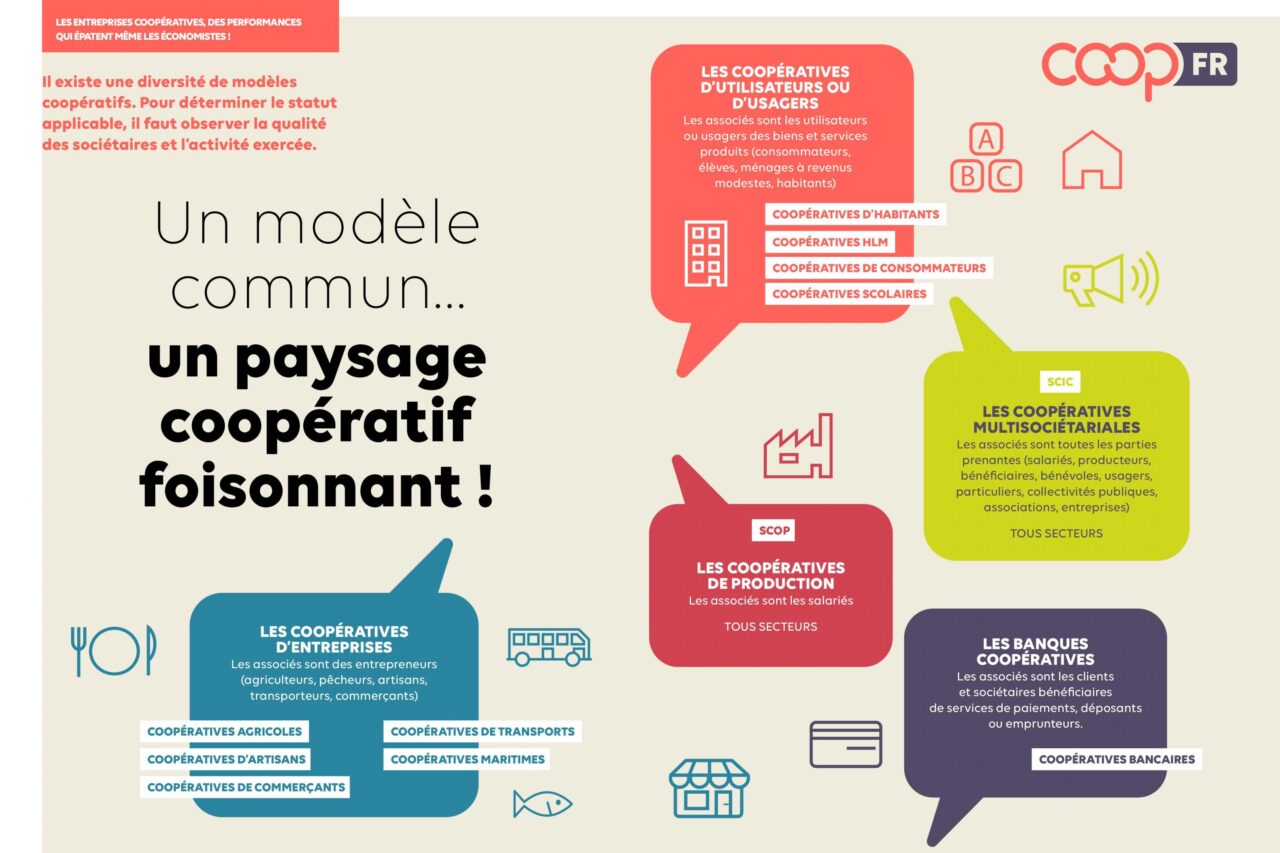

What are the structures of the social economy?

The law distinguishes between :

- statutory players that automatically come under the SSE umbrella by virtue of their status: cooperatives, mutual societies, associations and foundations;

- ESUS-certified companies (entreprise solidaire d’utilité sociale) that meet the above criteria.

Not all SSE structures are for-profit organizations.

Find out more about the different types of structure on the BPI France website.

Without going into the details of all types of structures, we’ll concentrate here on two examples.

The mutual company (or mutual 34 ) is, under French law, “a non-profit legal entity governed by private law”, registered with the Registre national des mutuelles and subject to the provisions of the Mutual Societies Code . It pays no dividends, and all profits are invested for the benefit of its members.

The purpose of mutuals is to cover risks (health, various types of insurance). Members are the mutual’s customers. Based on the principle of one member, one vote, they elect delegates who, meeting at a general meeting, decide on the terms and conditions of the contract. 35 They in turn elect the members of the Board of Directors (who are also members of the mutual). The Board has specific supervisory prerogatives (see the Mutual Code for details), including the right to appoint the operational manager. As you can see, members play the same role here as shareholders in a company. It should be noted, however, that sovereign power is by construction very diluted, due to the principle of one member, one vote.

Cooperatives

The legal basis for all cooperatives is set by the 1947 law on the status of cooperation, which defines a cooperative as “a company formed by several people voluntarily united to meet their economic or social needs through their joint efforts and the establishment of the necessary means”. (Art. 1)

Each member has one vote at the Annual General Meeting, and profits must be reinvested in the cooperative as a priority. Surpluses may, however, be paid out to members, under conditions defined by the laws specific to each type of cooperative.

There are several main types of cooperatives

Not all cooperatives have the same legal form: for example, SCOPs and SCICs take the form of limited companies or SARLs, while agricultural cooperatives “form a special category of companies, distinct from civil companies and commercial companies” (see art. L521-1 of the French Rural and Maritime Fishing Code).

Finally, it’s worth noting that cooperatives bring together structures with a wide variety of purposes, some of which raise the question of their social utility (if not in their purpose, at least in their implementation). Crédit Agricole, for example, is a cooperative bank. 36 . It is also one of France’s four systemic banks.

SCOP (Société coopérative et participative) governance

In a SCOP, employees are at the heart of governance. They must hold at least 51% of the share capital and 65% of the voting rights, which are organized according to the “one person, one vote” principle. In this way, employees take the decisions that concern them most, notably by electing the SCOP’s managers and validating the major strategic orientations at the Annual General Meeting.

In addition, profits are obligatorily divided into three parts: the “company share” refers to the non-distributable reserves, which remain within the company; the “labor share” is redistributed to employees; and the “capital share” is paid out to associates (employees and non-employees) in the form of dividends;

In 2023, there were some 2,697 Scops in France, employing 60,000 people (70% of whom were associates) and generating sales of nearly 8 billion euros. Although they are generally small, they also include some very large, sometimes multinational companies, such as the Up group (formerly Chèque déjeuner). Scops also differ from one another in that some are highly militant, with a project for social transformation; others are primarily concerned with economic results.

Source Find out more: Anne-Catherine Wagner Cooperate. Scops and the collective interest factory CNRS éditions, 2022. The Confédération générale des Sociétés coopératives website.

Alternative models for “classic” commercial companies

Beyond the SSE, there are other forms of governance that ensure that, while profit is not rejected, its maximization is not the priority compass of management.

These alternatives are more far-reaching than simply displaying good corporate social responsibility and environmental practices, which remain subordinate to the imperative of maximum profitability. They involve alternative statutes or specific legal provisions that ensure that the company is not enslaved to financial performance alone, without abandoning the possibility of making profits and remunerating capital.

Shareholder foundations

Born in Northern Europe in the 1920s 37 the “shareholder foundation” model is a corporate ownership and governance model that responds to the desire of the shareholders (often the founders) of a commercial company to preserve the company’s project and protect it over the long term (against hostile takeovers, demands for returns, etc.).

In practical terms, shareholders give a foundation their shares (in part or in full) and the associated voting rights, in a proportion that can vary (it’s not necessarily one share = one vote) and whose number determines the foundation’s decision-making power, as a shareholder, over the company’s strategy.

Since it belongs to no one and cannot be bought out, the foundation protects the company’s capital and its project according to the mandate given to it. By definition, it is a shareholder of general interest, stable and long-term. Thanks to dividends or other donations, it can also carry out a philanthropic mission by supporting causes in the public interest.

The foundation shareholder is not in competition with other shareholders to demand higher returns; it can therefore demonstrate “temperance” in this area, especially as it has an objective interest in ensuring the long-term viability of the company, which is its sustainable source of financing.

Some foundations are able to do without dividends; others define dividend distribution rules designed to ensure the financing of the investee company’s development.

But “status does not make virtue”, and some shareholder foundations receive significant dividends. What’s more, having a foundation as a shareholder is obviously no guarantee of optimized environmental and social performance.

In France 38 Adam, Naos, Léa Nature, Laboratoires Pierre Fabre and Institut Mérieux, for example, are partly owned by shareholder foundations. In Europe, many other companies are in the same situation: Baur, BMW, Bosch, Carlsberg, Electrolux, Lego, Maersk, Migros, Rolex, Saab, SEB, Velux, Victorino, Carl Zeiss (one of the first)…

Mission-driven companies

Following the Notat-Sénard report 39 the Pacte Act of 2019 introduced the concept of a mission-driven company 40 along the lines of what already existed in the United States.

When a company wishes to obtain this status, it must define its raison d’être and social and environmental impact objectives in its articles of association. It must also set up a “mission committee” made up of various stakeholders responsible for monitoring and evaluating the execution of the mission (which is also monitored by an accredited independent third-party organization).

The mission-driven company is a step forward, as it enables managers to constructively oppose any pressure from shareholders for greater profitability if it contradicts the mission, and vice versa. In June 2024, there were some 1,650 mission-driven companies, mainly SMEs but also a few ETIs and a few large corporations.

It should be noted that the Pacte law also created a new form of shareholding via the “fonds de pérennité”, a hybrid structure, enjoying legal personality, allowing the holding and transfer of company shares (this is its primary purpose) and which can support causes of general interest.

The steward ownership movement

The concept of ” steward ownership ” was coined by the Purpose Foundation 41 to propose a “third way” for companies, between shareholder primacy and non-lucrativeness.

This model has the following objectives:

- put the people really involved in the company back at the heart of governance;

- align governance structures with a long-term vision, serving the company’s mission;

- link voting rights to interests other than financial ones;

- propose a new form of succession, which ensures a company’s longevity beyond its founder, while limiting the spread of inequalities through inheritance by democratizing capital.

This model is organized around two principles:

- “Self-governance: control of the company remains within the company, in the hands of people directly involved in its mission.

- “Profits serve purpose”: profits serve the mission and are reinvested in the company, its stakeholders or philanthropic initiatives. Limited “fair compensation” is offered to investors.

It can take the form of two families of devices:

- shareholder structure: the shareholder foundation, the perpetual purpose trust

- statutory mechanisms: creation of non-voting shares for investors (with preferential dividend), shares with double voting rights and/or without dividend granted to long-term stakeholders, golden share (share with veto right) entrusted to a third-party organization (foundation, State, NGO, etc.) to guarantee the pursuit of the mission, etc.

To date, around a hundred companies have been supported by the Purpose Foundation, including Bosch, Novo-Nordisk, Mozilla and Stapelstein. 42 … The Purpose Foundation cites several studies 43 which show a higher survival rate and better financial performance for foundation-owned companies in Denmark (a pioneer in the field of shareholder foundations).

However, it is still too early to draw any definitive conclusions as to whether these new models are leading to a better integration of planetary limits into decision-making; moreover, they are currently limited in number, by their “voluntary” nature and by certain legal difficulties (in France). They do, however, have the immense merit of showing that the quest for accounting profit (see our module on corporate accounting) and the general interest are not irreconcilable.

Find out more

- Corporate governance, Pierre-Yves Gomez, PUF, Que sais-je? collection, 2018

- Heart Leadership University’s research on governance

- Prophil’s research on shareholder foundations and mission companies

- Steward-Ownership. Rethinking ownership in the 21st century, Purpose Foundation, 2019

- Structure and diversity of current models of corporate governance – Part I and II, Christophe Clerc, ILO reports, 2020

- The social and solidarity economy. Timothée Duverger, La Découverte, 2023

- Codetermination: employees have their say, France Culture podcast, 2024

The focus on maximizing shareholder profit poses numerous ecological and social problems.

From the 1970s onwards, the idea that a company’s primary objective should be to maximize profits in order to remunerate its shareholders (see Misconception 2) was widely accepted. 44 This doctrine, which has the force of evidence for many, is reflected in reality by numerous negative impacts, or at least by a strong tension between the need for financial profitability and respect for environmental and/or social constraints.

Expected returns on financial capital and planetary limits

A company subject to high financial profitability requirements 45 is necessarily run with a high degree of pressure, whatever the human quality of the manager and his managerial talent.

Definition – What is the expected return on financial capital?

When a company is set up, the founder or founders contribute resources 46 to form the company’s share capital. This is divided into shares, allocated to the founders (henceforth referred to as shareholders) in proportion to their contribution. Ownership of these shares confers rights of participation in decisions taken by the company’s General Meeting, as well as financial rights (via the payment of dividends). Once issued, shares can be sold either through bilateral exchanges or publicly on organized markets (stock exchanges).

For shareholders, this capital is an investment that can generate income through the distribution of dividends when the company makes a profit, and also increase in value if the value of the shares rises (if they are sold, the owner realizes a capital gain). The return on capital is what it brings back to the shareholder in at least one of these two forms.

A company is listed on the stock market because it promises a return, usually a high one, to attract investors. Contrary to popular belief, this expected return does not necessarily translate into immediate financial gains (dividends) for the shareholder. The promise of high returns can be fulfilled by share valuations alone (which can result from a variety of factors, such as brand awareness, sales growth, etc.). This explains why the shares of companies like Amazon or Tesla have enjoyed high valuations even though the companies themselves were loss-making.

In the face of such demands, environmental and social constraints whose observance is not made strictly compulsory by the legislator generally take second place, as they are likely to weaken short-term profitability and hence the return on capital.47

Even where standards exist, managers may seek to circumvent them, whether by outsourcing or relocating part of their business to countries with lower social and environmental standards, or by fraud (as demonstrated, for example, by “dieselgate“).

This is not to say that all companies with high profitability requirements do nothing for the environment or society. First of all, certain activities with a positive impact on the environment can enjoy significant growth and high financial valuations. Secondly, consumer pressure can be a driving force. Health scandals, social disasters (such as the collapse of the Rana Plaza in 2013) or environmental disasters can thus prompt management to change, under pressure from consumers, but more often than not in a reactive rather than proactive approach. Finally, the anticipation of tensions over raw materials can lead managers to encourage sobriety of use or accelerate recycling, without preventing them from maintaining significant profits. 48

But these are clearly exceptions. The best proof of this is that, despite numerous declarations of intent, our economy, “driven” by large multinationals (whose power is excessive, see Essentiel 10), is still very (and far too) extractive and carbon-based.

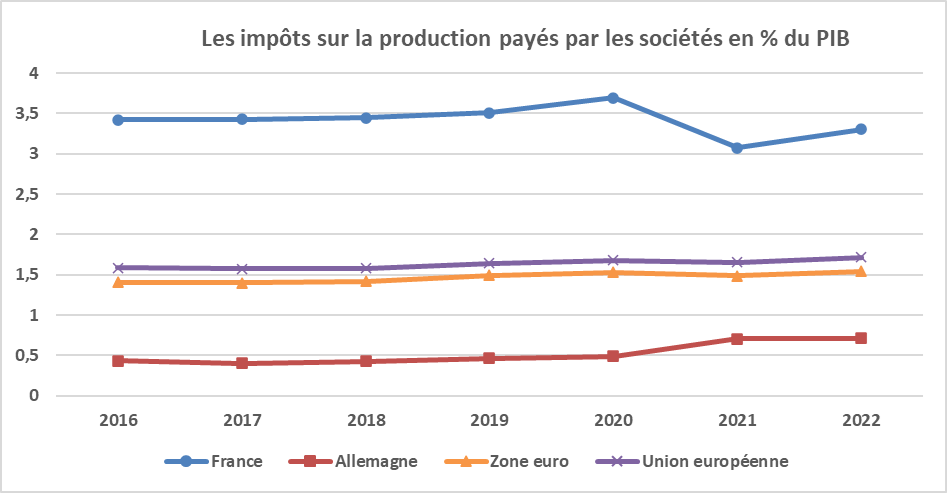

Finally, the expected rate of return on capital is decisive for financing the ecological transition. Current rates of return in financial capitalism are widely recognized as excessive. They are generally much higher than those that most ecological investment projects can deliver. However, this is not inevitable: on the one hand, these rates are the lowest in economic history; on the other, there are companies that are not subject to such pressure. The structures of the social and solidarity-based economy, the purpose-economy movement and steward ownership, which we presented in Essentiel 4 on the various forms of corporate governance, aim precisely to escape this “tyranny of return”.

A very narrow conception of the value created by the company

In reaction to the growing influence of the theory of maximizing shareholder value, numerous works have been developed to denounce the decline since the 1980s in the share of labor compensation in value added in the United States and Europe. 49 and to assert the importance of sharing value between shareholders and employees. These debates are regularly fuelled by scandals concerning dividends paid out by major corporations and share buy-backs.

What is added value?

In business accounting, added value is sales minus intermediate consumption (purchases of goods and services required for production). It is a management indicator that measures the financial value generated by the company once it has paid all its suppliers and service providers. It is divided between employee remuneration, taxes, investments and return on capital (debt and dividends).

At the macroeconomic level, GDP is made up of the sum of value added generated by all public and private economic players. This value added is also broken down into employee remuneration, capital remuneration, investment and public taxes.

Source To find out more, see our modules on corporate accounting and GDP, growth and planetary limits.

The subject of value sharing needs to be broadened beyond the mere question of capital and labor. Promoters of shareholder value identify the “value created by the company” with profit, which is very restrictive. It is much more sales that represent this value, the one for which customers pay.

Seen in this light, it’s clear that value is shared by all stakeholders: suppliers and service providers, employees, the public purse via taxes and social security contributions, shareholders via dividends, bankers where applicable, and finally the company itself (investments, development).

Each of these stakeholders receives “its share” according to either regulations (taxation, regulated professions, monetary policy), or the “market” (more or less regulated, more or less oligopolistic) and the resulting balance of power (between workers, managers and shareholders, between principals and suppliers, etc.). This is one of the reasons why the company is a source of both cooperation and conflict (see Essential 3): it is thanks to the coordinated action made possible by the company that each party “receives” its share, the share of each being limited by that of the others.

To reason in a binary way, by opposing labor and capital, is to forget all the other stakeholders who also suffer from the doctrine of shareholder maximization: suppliers and service providers, whose prices will be demanded as low as possible, and public authorities, through pressure to reduce taxes on companies, or to lower the standards imposed on companies to limit their nuisances.

Finally, while financial value is today’s dominant metric, it is only one dimension of a company’s overall capital and of value as such: companies have varying degrees of social utility (the latter sometimes being zero, or even negative); they often have negative impacts on the environment (see Essential 9); certain stakeholders may prefer a non-financial reward (e.g. reduced working hours, training, annualized contract for a supplier…) to an increase, etc.

Pay differentials and inequality

The level of executive compensation at major corporations is regularly in the news. Increases in this area are mainly the consequence of the predominance of the shareholder value doctrine, which has led to the interests of executives being aligned with those of shareholders, notably through remuneration (variable portion, bonuses, stock options, etc. seeMisconception 2).

This issue is not neutral in terms of social cohesion: when an executive is paid tens of millions of euros while his company is sold to the highest bidder 50 or engages in massive cost-cutting (even laying off staff or relocating), this sends out signals that are difficult for many citizens to bear.

It’s even more difficult if, at the same time, the government develops a rhetoric on the efforts to be made in terms of social rights such as pensions, unemployment or more generally to reduce public spending.

How are salaries set?

As a general rule, companies set salaries by comparison with practices observed for similar positions in comparable companies (size, business sector, financial performance, etc.). They may, of course, do a little better or a little worse, depending on the urgency of the recruitment and the more or less strategic nature of their needs for the positions in question. As a first approximation, however, it can be said that “the law of the market” applies to everyone. It will be difficult for an employee or a company to be paid a salary that is permanently very different from the market average.

The labor “market” does not necessarily remunerate work according to its “social value”.

The Covid crisis clearly showed that essential jobs were poorly paid and poorly recognized. Conversely, anthropologist David Graeber has highlighted the existence of “bullshit jobs“. 51 jobs that have no meaning, even for the employees themselves, even though they are well-paid and well-recognized. The exorbitant salaries of soccer or movie stars are sometimes “justified” by the “law of the market”, which cares neither for morality nor for consistency between the social value of the service rendered and remuneration. This is a matter for public intervention, as social cohesion is clearly at stake in the growth of unfounded pay disparities.

Wages are not based on labor productivity 52 contrary to what most economists believe. Productivity is generally impossible to measure, except in very specific and limited cases. And it is never completely individualizable: an employee’s contribution depends on the organization, the equipment at his disposal and his colleagues.

Salary may not be the only component of an employee’s remuneration, which may also include :

- the distribution of a portion of profits to employees: in France, this is the case with statutory profit-sharing for companies of a certain size, or with profit-sharing agreements.

- an annual bonus linked more or less objectively to performance.

- a stake in the company’s capital via a number of mechanisms (stock options, bonus share allocations, share subscription warrants, etc.). 53

- benefits in kind: luncheon vouchers, company-paid health insurance, company car or housing, etc.

In addition, executives may be awarded exceptional supplements (a welcome bonus, a severance bonus, a “top-hat pension”, etc.).

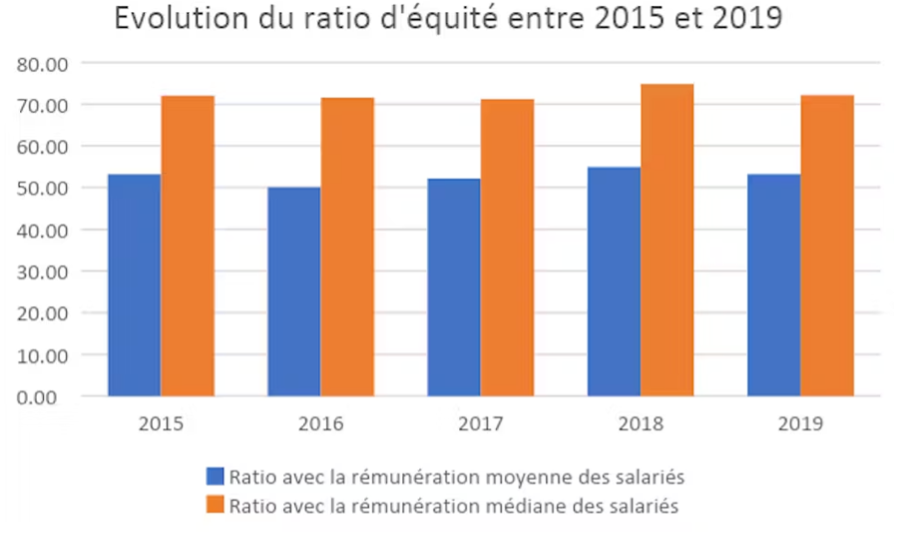

The equity ratio: the transparent way to limit pay disparities

One of the main ways in which governments have so far sought to influence pay differentials is through transparency: encouraging self-regulation by players by making data public.

Equity ratio compares total compensation 54 of the principal executive(s) to the average compensation of full-time employees in the company. For example, if this ratio is 100 in a company, this means that the CEO earns 100 times more than the average compensation of his employees.

Introduced since 2018 in the United States and the United Kingdom, it was introduced in European Union countries following the SRD II directive (2017). This was transposed in France by the Pacte law of 2019 55 which made it mandatory for listed companies to publish this ratio. 56

The equity ratio in the United States

In the United States, the equity ratio rose from 20 in 1965 to over 300 (or even 400) in the 2000s, before “falling back” to around 200 after the financial crisis.

CEO Pay in 2012 Was Extraordinarily High Relative to Typical Workers and Other High Earners – Economic Policy Institute (2013)

The equity ratio in Europe and France

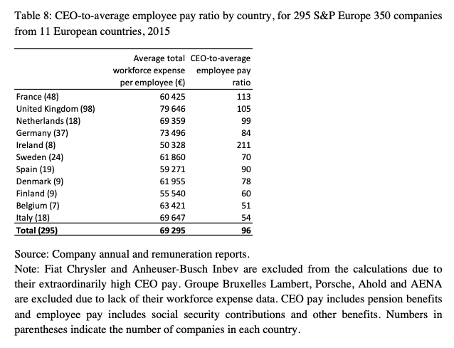

Ratio of CEO compensation to average salary

The ratio of CEO total compensation to average salary in 350 listed companies in 11 European countries in 2015 was 96.

Source Executive compensation in Europe: Realized gains from stock-based pay – INET (2018)

This article was subsequently published in a revised version in Review of International Political Economy: Patricia Kotnik, Mustafa Erdem Sakinç, Executive compensation in Europe: realized gains from stock-based pay, 2022.

In France, within the CAC 40, the ratio between the average income of CEOs (5 million euros) and the average compensation of their employees was 53 (72 in relation to median compensation) in 2019. This figure conceals major differences from one company to the next: for example, at Dassault Systèmes and Sanofi, the equity ratio was 268 and 107 respectively.

Source Rémunération des dirigeants : la transparence ne fait pas tout, Mohamed Khenissi, Vanessa Serret, The Conversation (27/07/2020).

Many critics have questioned the value of this ratio.57

- Statistics are particularly sensitive to changes in CEO income alone. Much more volatile than average salaries, it is often the primary explanation for changes in equity ratios.

- As with any indicator, this ratio is open to interpretation. For example, in France, as the law does not specify a perimeter, it is possible to calculate the equity ratio on the basis of the parent company alone, which is often a holding company with a few dozen employees, which leads to an underestimation of the ratio compared with what it would be if the entire group were taken into account. Thus, based on declarations alone, the 2024 edition of the CSR Criteria and Remuneration study evaluates the equity ratio at 73 in 2023 for CAC 40 companies. “Calculations by the voting consultancy Proxinvest Glass Lewis give different results: an average ratio of 130 in favor of CAC 40 executives for the year 2022.”” 58

- The equity ratio is limited to a comparison between the remuneration of key executives (or even the CEO alone) and average earnings. It would be far more interesting to understand the distribution of income in greater detail, in particular the gaps between the first decile or percentile (depending on the number of employees) and the other deciles within the company, as is the case with any measure of inequality.

Finally, and most importantly, transparency and goodwill are not enough to achieve the goal of limiting income disparities.

Several years after its introduction in France, the equity ratio has had no tangible effect on pay differentials. Very few investors have used it as a shareholder governance tool, and its impact on the general public has been weak. 58

Only voluntary action by public authorities can have a real impact, as proposed by Gaël Giraud and Cécile Renouard(who suggest establishing a ratio of 12 between maximum and minimum wages).