This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

The issue of inequality is a complex one: studying inequality means looking at how goods or wealth are distributed on different scales (local, national or international). The notion of inequality is often associated with that of poverty, which refers to financial or material inadequacy.

The emergence of inequalities – where do they come from, how long have they existed? – is still an open debate. While some consider them to be inherent to human nature, others have studied them from the angle of social and political construction. 1 While the debate remains unresolved, one hypothesis put forward is that the economic stratification of society was concomitant with the onset of sedentarization, over 10,000 years ago.

According to economist Thomas Piketty, the evolution of monetary inequalities since the end of the 18th century is characterized by a “historic movement towards equality”. 2 However, this global perspective conceals significant disparities and certain new trends since the 1980s.

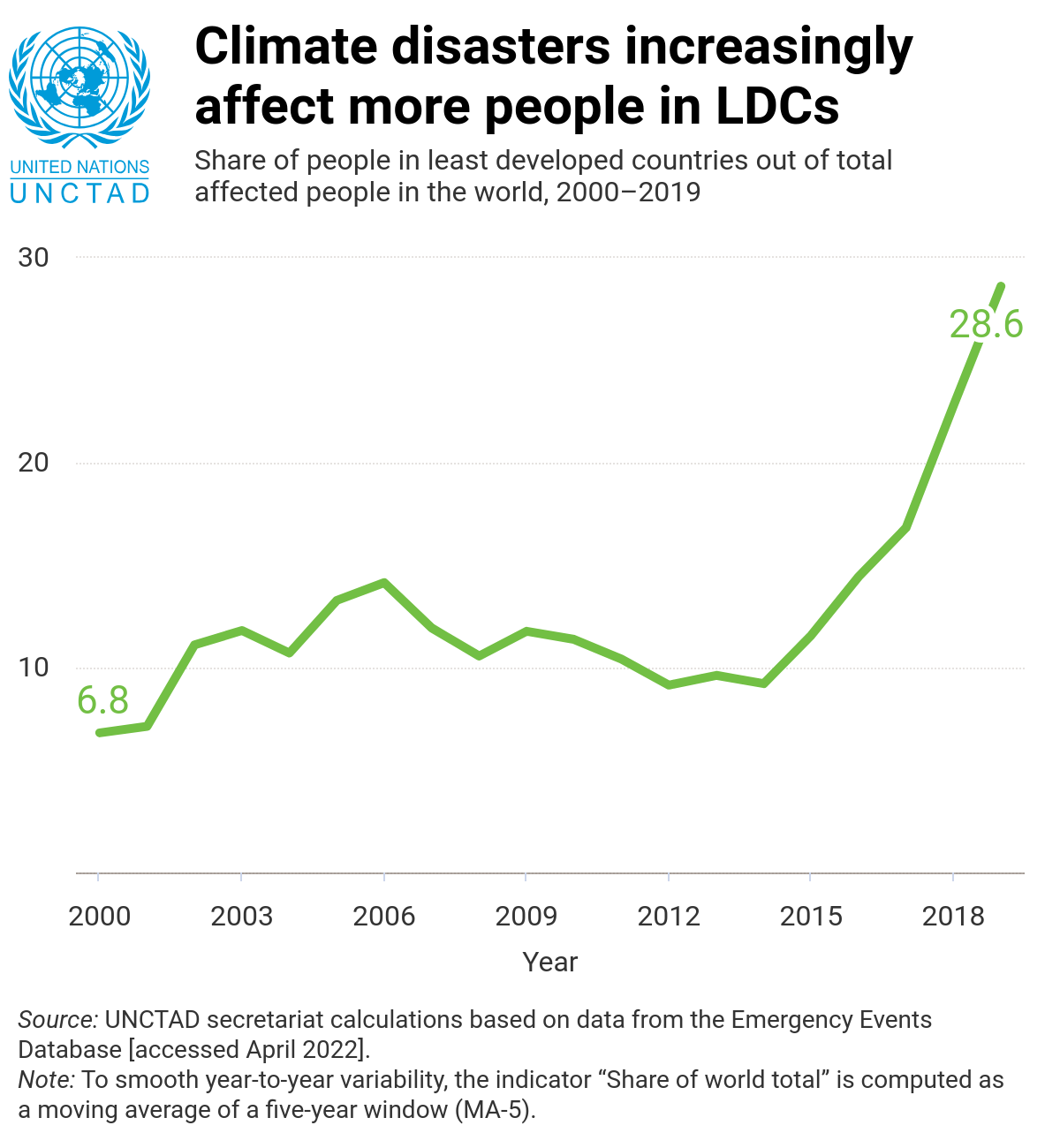

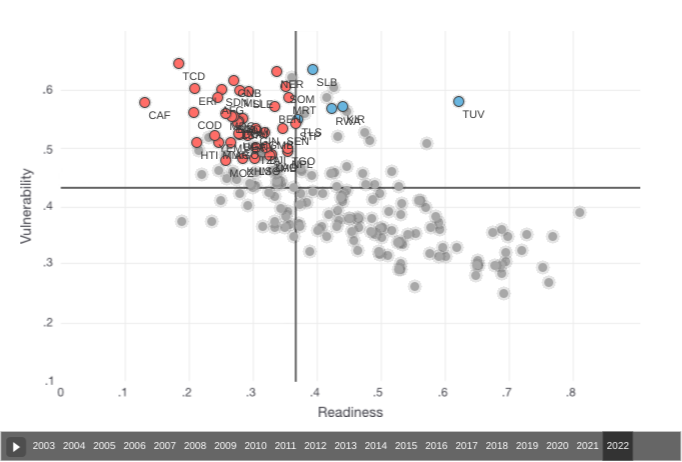

Furthermore, limiting inequalities to monetary inequalities is insufficient: inequalities are multidimensional(see Feature 1). A remarkable example, and one increasingly present in public debate, is that of environmental inequalities. Climate change, and ecological crises more generally, have highlighted a number of environmental inequalities 3 :

- inequalities in exposure to ecological crises, in access to the environment, and in the ability to adapt to crises(see Essentiel 11),

- impact inequalities (for example, inequalities in terms of contribution to pollution – see Essential 4 and Misconception 5),

- inequalities induced by environmental policies(see Feature 9),

- inequalities in terms of influence on the implementation of environmental policies by a country or region(see Feature 9).

The essentials

Inequality is not just a question of money

The question of inequality is, for the most part, addressed in public debate from the angle of income and wealth. Although the monetary aspect is indeed an important dimension of inequality, there are others, sometimes less visible (or less watched).

Legal inequalities

For proof of this, we need look no further than the statutory inequalities that are, or have been, enshrined in the law of certain countries. It was only in December 1948 that the General Assembly of the United Nations – then made up of 58 countries – adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the first article of which stipulates that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights”.

Let’s take three unavoidable cases: Indian castes, women’s rights and discrimination before the law based on skin color.

India’s caste society is an example of a social body long marked by status and structural inequalities. 4 It was not until the Indian Constitution of 1950 that all forms of caste-based discrimination were officially abolished. Almost 80 years later, India remains one of the most unequal countries in the world. 5 Despite quota policies, people from disadvantaged castes are still largely under-represented in certain fields – intellectuals, for example. 6

On the other side of the globe, women’s right to vote only arrived in the 20th century in most Western countries (1920 in the USA, 1944 in France, 1971 in Switzerland…). In France, it wasn’t until 1965 that married women could work or open a bank account without their husband’s authorization. 7

Inequality before the law according to skin color is another major example in many countries, with black people long denied the same rights as light-skinned people. In concrete terms, this translated into slavery in colonized countries for several centuries (from the late Middle Ages to the 19th century). 8

After the abolition of slavery, some states enacted other laws perpetuating statutory inequalities between black and white people. This was notably the case in the United States with the Jim Crow laws enshrining, among other things, racial segregation in public places (the principle of these laws being summed up by the doctrine of “separate but equal”). 9 Following the civil rights movements of the 1950s-1960s, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 put an end (officially – see Idea 8) to segregation and guaranteed equal civil rights regardless of skin color, origin, religion or gender.

De facto inequalities

It should be noted here that these de jure inequalities result in monetary inequalities, and that the abolition of discrimination in law does not instantly translate into its effective disappearance. In particular, despite significant progress in recent decades, de facto inequalities between women and men still persist throughout the world.

Economist Amartya Sen points out that some inequalities lead to others. In particular, he argues that the principle of equality should not be based solely on interpersonal comparisons of resources (wealth, income), but on the ability of individuals to transform these resources into freedoms.

In 1979, he introduced the notion of “capabilities”. 10 These refer to an individual’s ability to convert his or her “resources” (economic, but also cognitive, in terms of education, networks, etc.) into opportunities andsubstantive freedoms, enabling him or her to lead the life he or she wants to lead. 11 His work has been the driving force behind a new approach to questions of poverty and inequality, which is not based solely on questions of income, but focuses more on capabilities and the deprivation of capabilities. 12 This approach emphasizes the fact that sources of inequality can add up. 13

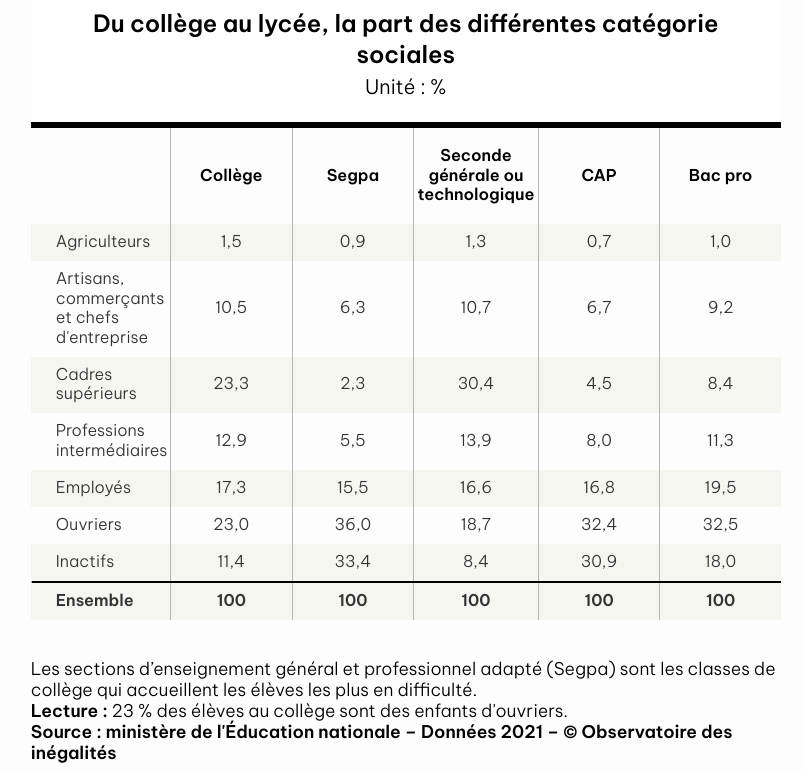

Cultural, social and economic capital – not all heritages are financial

According to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, different forms of “capital” interact and contribute to shaping the social trajectories of individuals (we’ll use the term “capital” in the Bourdieusian sense in the remainder of this box only). This dynamic tends to perpetuate social and monetary inequalities from one generation to the next – which cannot be explained solely by the transmission of economic wealth (inheritance, for example).

Pierre Bourdieu distinguishes four forms of capital: economic, cultural, symbolic and social.

For example, social capital, made up of social networks and community ties, is generally passed on through family and professional relationships, providing access to economic and social opportunities. In concrete terms, a young entrepreneur from an entrepreneurial and international background will tend to have a large network (social capital), offering him or her economic development opportunities.

Another well-known example is that of cultural capital: in their book Les Héritiers (1964), Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron emphasize the key role played by the cultural capital passed on by families in their children’s ability to pursue rewarding studies, guiding them towards remunerative and stimulating careers. In practice, this can mean that parents from upper-class backgrounds “know the system better”, know how to deploy strategies to get their children into the most prestigious universities, or introduce their children to “classical culture” from an early age.

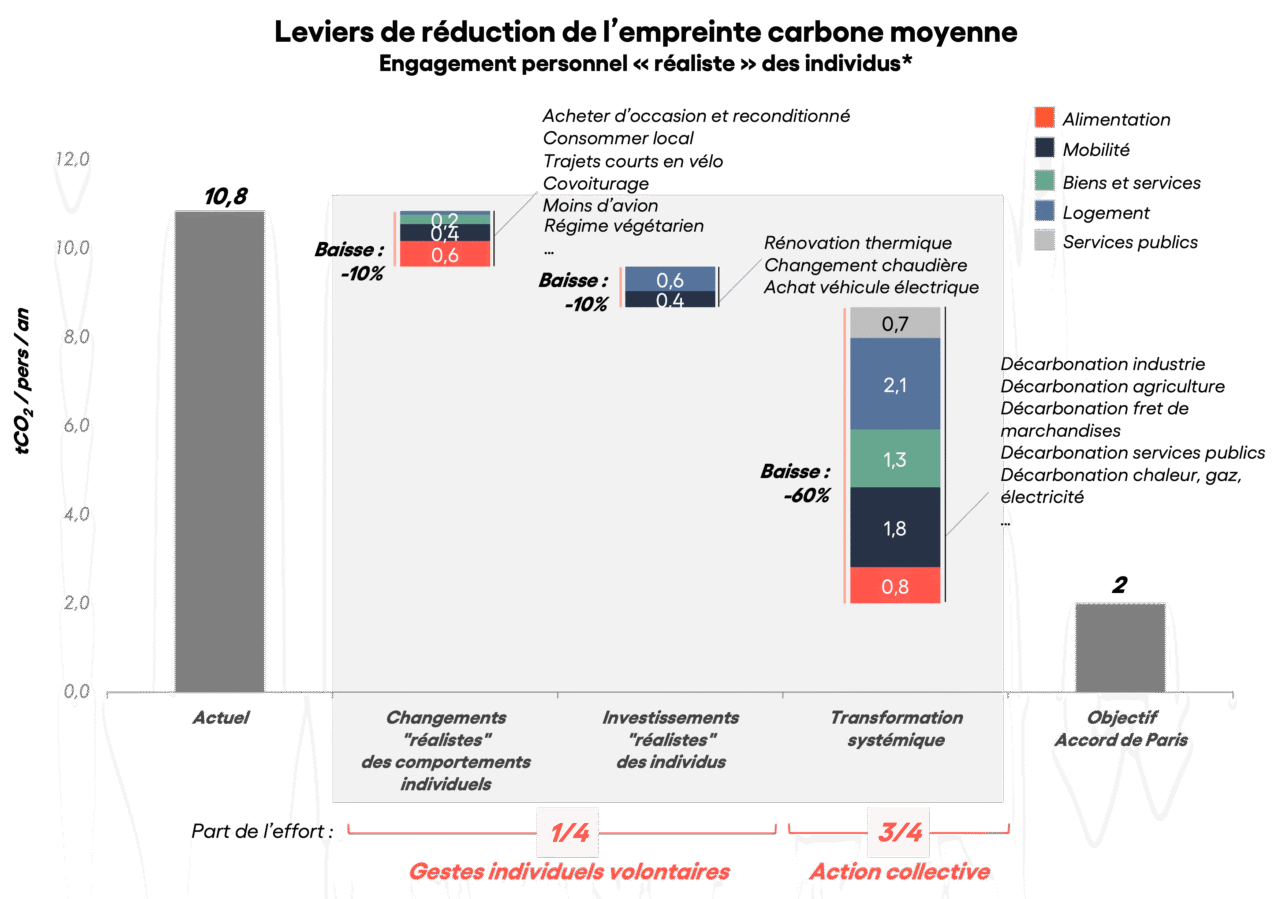

Another cardinal dimension of inequality is the link with ecology; the question of ecological transition cannot be addressed without considering the social question (see Essentiels 4, 9 and 10 in particular). To illustrate this, let’s quote sociologist Sophie Dubuisson-Quellier:

“The intersection of social and ecological issues actually generates three types of inequalities: inequalities in exposure to environmental problems, […]; inequalities in greenhouse gas emissions, because the lifestyles of the richest people emit more; and finally inequalities in effort, because part of the population – often the least advantaged – will incur greater economic costs as a result of implementing measures linked to the ecological transition.”

Finally, there are other sources of inequality, such as access to public services, which are strongly felt by those who suffer from them. 14 The source of these inequalities can be geographical: this can occur on a global scale – depending on the country of birth, access to healthcare or education can be more or less socialized – and on a national scale – with, for example, in France, the case of “medical deserts” mainly located in rural areas (which constitute inequalities in access to healthcare). To illustrate this, let’s conclude with a quote from Olivier Passet:

“First of all, we need to be aware that our monetary indicators give only a very partial picture of inequality. Among the blind spots is the fact that, for the same level of monetary income, households in some countries have access to a wide range of collective services, the cost of which is socialized, particularly in the fields of health, education, training and employment services, while in others they do not. Depending on the country, these services may be of good quality, uniformly accessible or, on the contrary, deteriorating. This is precisely where equal opportunities are built. And it’s clear that this is one of the decisive dimensions in building social cohesion.”

Find out more

- Development as Freedom, Amartya Sen, Oxford University Press, 1999

- Eric Monnet, La théorie des “capabilités” d’Amartya Sen face au problème du relativisme, Tracés. Revue de Sciences humaines, 2007

- Social Inequalities, Nicolas Duvoux, PUF, 2017

- Valérie Erlich, “Les Héritiers”: what Bourdieu and Passeron taught us about inequality of opportunity, The Conversation, 2022

- Philippe Testard-Vaillant, Comment l’orientation scolaire renforce les inégalités, CNRS Le Journal, 2018.

- Nearly 2.4 billion women in the world do not have the same economic rights as men, World Bank, 2022

- Inégalités : 12 graphiques de la vie d’une femme (France), Alternatives économiques (10/07/2024)

- Deepa Narayan, Poverty Is Powerlessness and Voicelessness, IMF, 2000

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom, Library of Congress

- The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress

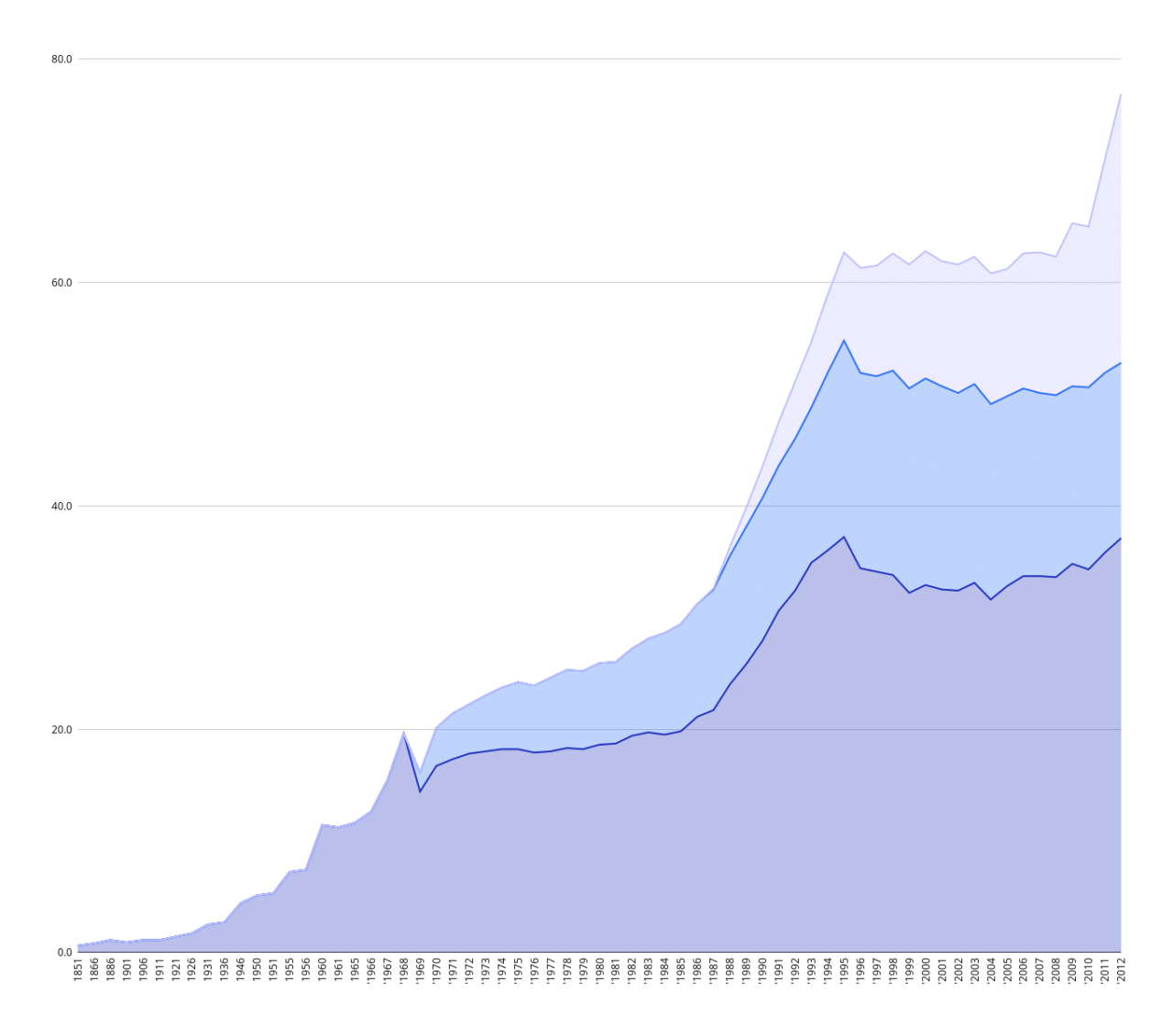

The average living standard worldwide have never been higher

Since the beginning of the 18th century, per capita income has risen considerably worldwide, largely thanks to the Industrial Revolution.15

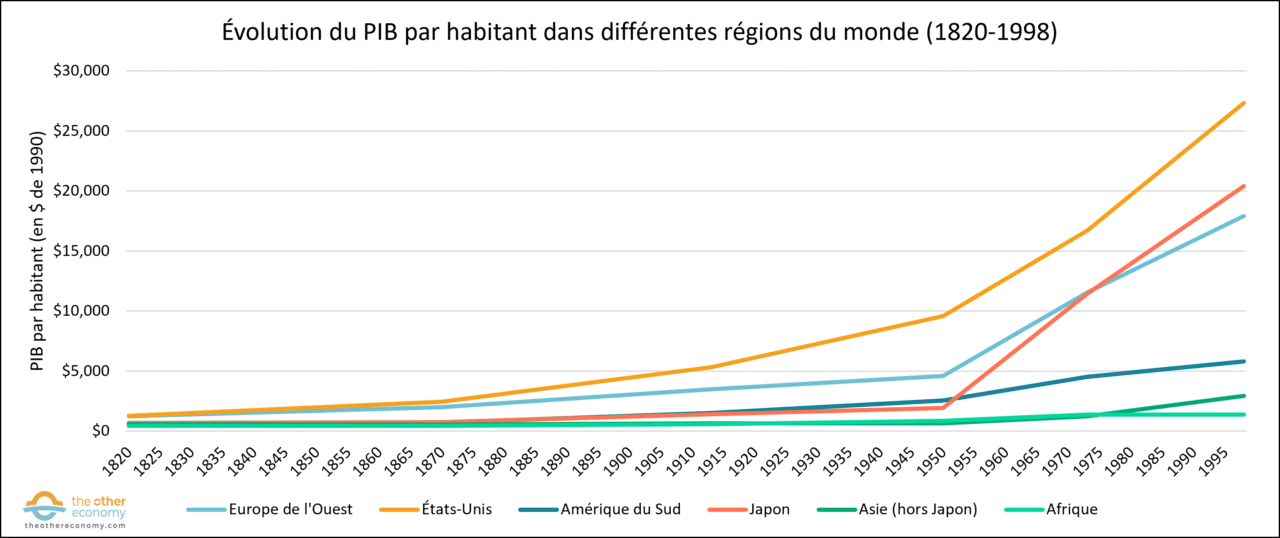

This dynamic is well illustrated by Angus Maddison’s work on economic growth over the very long term, which also shows disparities between regions of the world: whereas in the 15th century, per capita incomes in the various regions of the world were comparable, the industrial take-off of Europe and the United States in the 19th century widened the gap between the West and the rest of the world.16

Evolution of GDP per capita in different regions of the world between 1820 and 1998

Source Angus Maddison, The World Economy, A Millennial Perspective, OECD, 2001.

This growth has come at the cost of overexploitation of natural resources, massive pollution of soil, surface water and oceans, and the destabilization of major natural balances, including the climate (see our Economy, natural resources and pollution module).

In 1820, GDP per capita in Western Europe and the United States was twice the Asian average. This gap widened even further between the 1950s and 1970s (excluding Japan) – in the context of post-war reconstruction, the Marshall Plan, the Cold War and the decolonization process.

It was only in the 1970s that the first Asian countries – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore – finally caught up. Since then, per capita GDP has risen sharply in China and, more generally, in Asia. This significant rise in living standards in Asia has led to a sharp reduction in the rate of extreme poverty. 17 from 38% in 1990 to less than 15% in 2019. 18

Today, sub-Saharan Africa alone accounts for 60% of the world’s population living in extreme poverty. In the words of the United Nations 2023 Sustainable Development Goals Report:

If current trends persist, an estimated 7% of the world’s population – around 575 million people – will still be living in extreme poverty by 2030, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa. This projection would represent a small reduction in poverty of less than 30% since 2015.

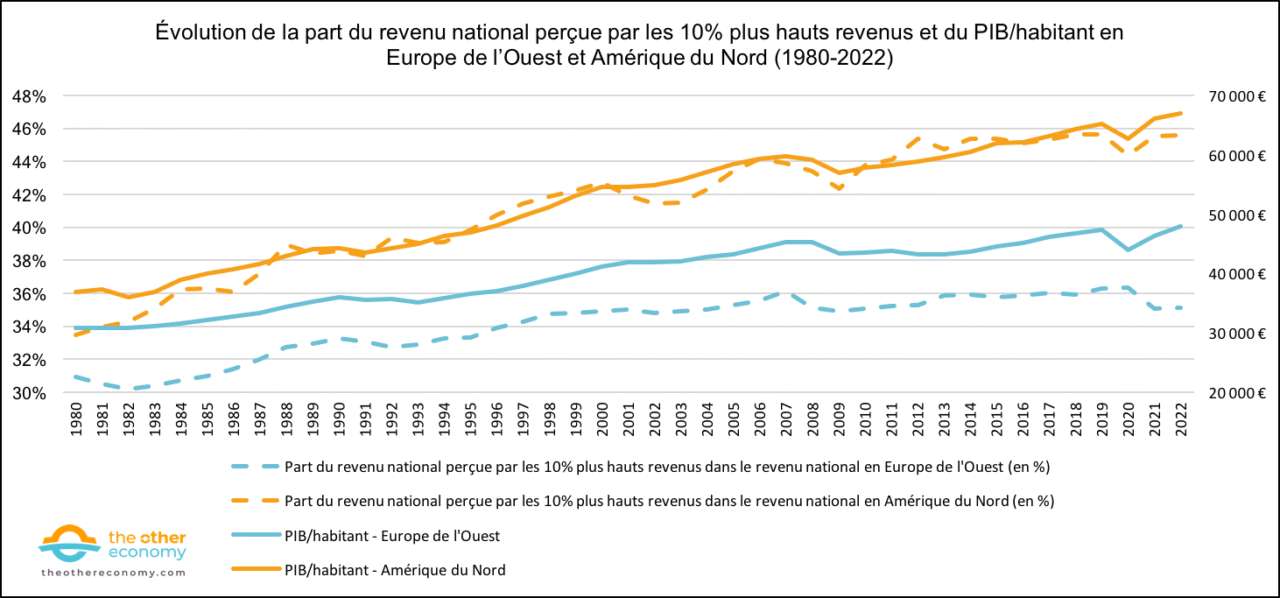

Income inequality has risen sharply in recent decades in developed countries

As detailed in the fact sheet on monetary inequality, there are a number of indicators that can be used to quantify income and wealth inequality within a country. However, whatever the indicator used, the same conclusion can be drawn: in developed countries, the level of inequality has been rising since the early 1980s. On the other hand, as we shall see inMisconception 1, inequalities between countries have tended to decrease over the same period.

Growing inequalities over the past 40 years

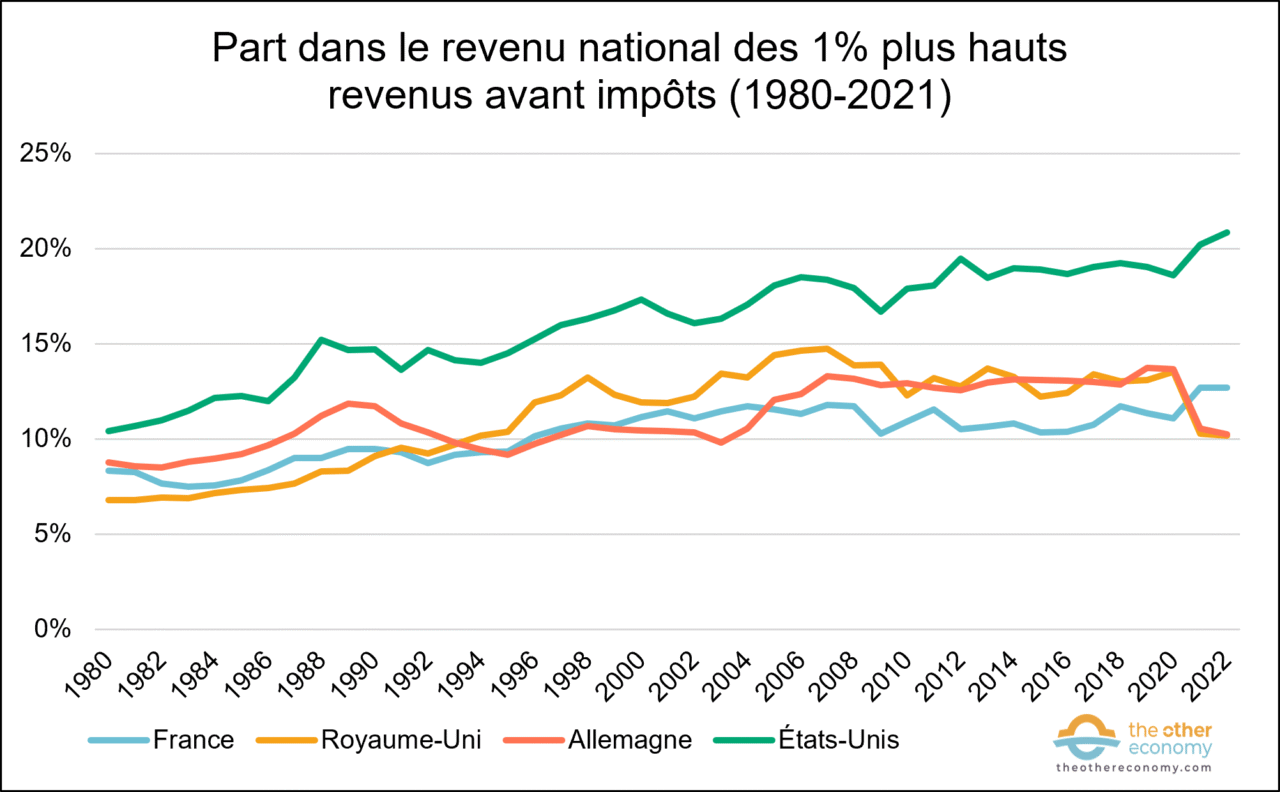

To underline this, we can look at the Gini coefficient 19 – on the rise 20 in the United States, Germany and the United Kingdom since the 1980s. The same is true of the share of the top 1% of income earners 21 of national income. Whether in the USA, France, the UK or Germany, this share increased between 1980 and 2020 – with, it should be noted, stagnation in some countries since the early 2000s, or even a slight reabsorption of inequality following the financial crisis of 2007-2008. 22

Overall, the share of high-income earners increased between the 1980s and 2020s

Reading : In 1980, in France, the top 1% of households accounted for 8.3% of national income.

Source: World Inequality Database

This widening inequality has been much more rapid and marked in some countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, than in others, such as France or Germany.

These differences are mainly due to the fact that social transfers and progressive income and inheritance tax policies are more important in France, for example, than in the United States(see Essentiel 6 on redistribution).

The elephant’s curve

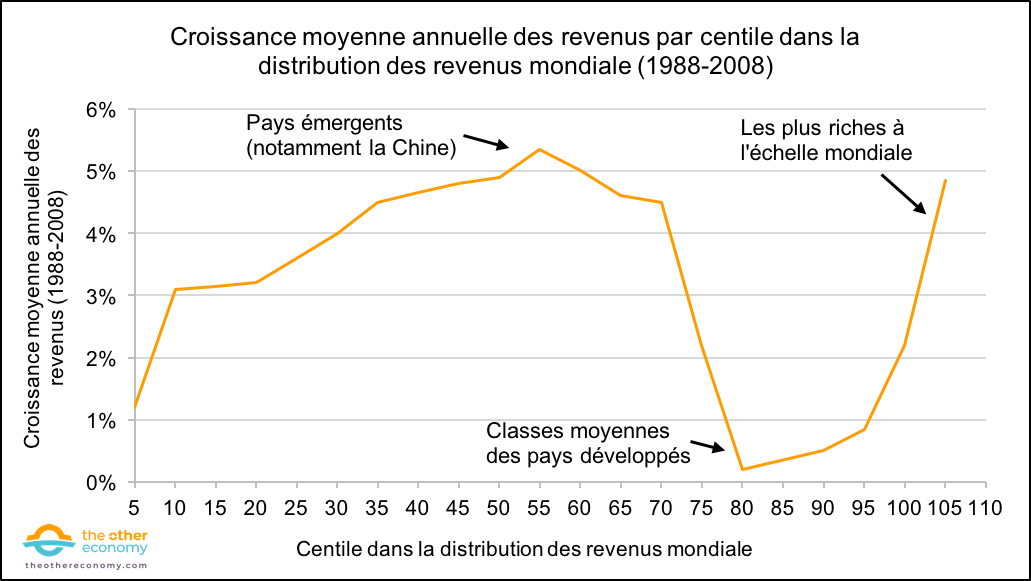

To better observe recent trends in monetary inequality within developed countries, we can also refer to the graph by Lakner and Milanovic, better known as the “elephant curve.”

This curve shows the annual growth in household incomes worldwide between 1988 and 2008, according to income level.

The elephant curve by Lakner and Milanovic (1988 – 2008)

Reading: the top 1% of global income earners saw their incomes grow by around 4.8% a year between 1988 and 2008.

Source Christoph Lakner, Branko Milanovic, Global Income Distribution: From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession, The World Bank Economic Review, 2015.

The elephant curve highlights various elements in the evolution of inequality over this period:

- a sharp rise in incomes in the middle of the global distribution (what Milanovic calls the “China effect”). For a long time, and particularly between 1988 and 2008, the reduction in global inequalities was based on the rapid growth of China, whose population represented a significant proportion of the world’s poorest 20%,

- the increase in inequality in developed countries over this period. Indeed, there was very modest or near-zero growth around the 80th percentile of the distribution – corresponding to the lower middle classes in the most developed countries – as well as a sharp increase among the world’s richest 1%.

The impact of the 2008 financial crisis

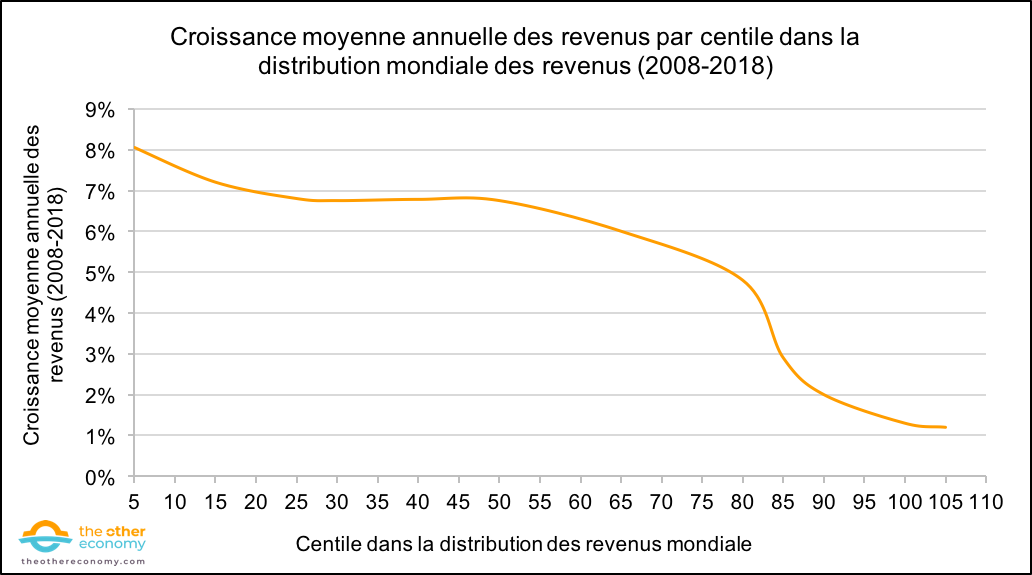

As Branko Milanovic points out in an article published in 2024 23 the situation described by the elephant curve is no longer valid at the time of the 2008 financial crisis, which, in his words, is “probably the most important development since the industrial revolution”.

Between 2008 and 2018, there was a significant reduction in income growth for the richest 1%, who were hit hard by the 2008 financial crisis. On the contrary, during this same decade, the strongest growth concerned the world’s poorest.

However, this evolution does not imply a de facto reduction in global inequality. Insofar as China is now a middle-income country (and its population is no longer heavily represented in the poorest 20%), its continued growth no longer reduces global inequality. On the contrary, it risks contributing to widening global inequalities, as the income gap between China and the poorest African countries widens.

The 2008 crisis changed the shape of the elephant curve

Reading: the top 1% of global income earners saw their incomes grow by around 1.2% a year between 2008 and 2018.

Note: Despite the shape of the curve, which attests to faster growth in the lowest incomes between 2008 and 2018, orders of magnitude must be taken into account: while in 2008 the 10% lowest incomes had an annual income of around $400 PPP, the 1% highest incomes had an annual income of over $50,000 PPP. Despite stronger growth in low incomes over this period, wealth disparities remain very significant on a global scale.

Source Branko Milanovic, The Three Eras of Global Inequality, 1820-2020, with the Focus on the Past Thirty Years, World Development, 2024.(download the preprint here)

Finally, as we pointed out in our How to measure poverty? monetary considerations are not sufficient to fully characterize poverty.

That’s why we’ve introduced the notion of “multidimensional poverty”, which characterizes poverty by taking into account access to education, health, food and so on.

For example, in 2022, 2.4 billion people in the world were food insecure (i.e., people without access to healthy, nutritious food in sufficient quantity throughout the year): of these, 750 million suffered from hunger.24

Not everyone benefited from free trade and free movement of capital

The recent rise in inequality can also be explained by the promotion of free trade since the 1980s. 25 The last forty years have been marked by a determination to eliminate customs duties and trade barriers between countries, which, according to neoclassical economists, should ultimately stimulate economic growth and benefit everyone.

Nevertheless, it has to be said that free trade has contributed to widening income inequalities within wealthy countries, and to enriching the wealthiest. In 2007, Paul Krugman, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, conceded as much 26 and promoter of free trade in the 1980-90s.

“It’s no longer safe to say that the effects of trade on income distribution in rich countries are fairly minor. There is now good reason to say that they are important, and becoming increasingly so.”

In particular, competition from imported products from countries with low labor costs (and low environmental standards) has pushed down low wages in developed countries.

The automotive industry in the United States provides a concrete illustration of this phenomenon, all the more relevant given its significant weight in the economy. Since the 1980s, low-cost imports of vehicles from Asia have had a major impact on jobs in this sector, particularly in the blue-collar sector. This has resulted in a fall in real hourly wages (i.e. taking inflation into account) of over 20% between 1980 and 2018. 27

What’s more, faced with a cheap and flexible workforce 28 mainly in Asia, and rising unemployment in the West, policies to make work more flexible have been put in place in Europe and the United States in particular – with part-time work, the development of temporary employment agencies, and so on. 29 As pointed out in a 1996 report commissioned by the French Prime Minister, such measures – which were supposed to reduce unemployment and boost economic activity – have actually contributed to worsening income inequalities, failing to encourage training, and creating mostly precarious, temporary, low-paying jobs. 30 This dynamic has been amplified since the 2010s with the uberization of certain professions (delivery drivers, among others). These workers are often in a precarious situation – on an EU scale, 55% of them earned less than the minimum hourly wage in force in their country in 2021. 31

Finally, the liberalization of capital flows and, more generally, the financialization of the economy have also contributed to the growth of internal inequalities within developed countries.

This liberalization has, in fact, mainly benefited wealthy individuals, offering them greater access to sources of financing and new investment opportunities abroad. Predictably, it is mainly the wealthy who can take advantage of these opportunities – the middle and lower classes having little or no access to international markets. What’s more, people working in the financial industry (banks, investment funds) in particular have seen their salaries soar in recent decades – not least via the annual bonus system – contributing to a widening gap with the rest of the population. 32

In recent years, capital owners have been able to diversify, secure and increase the income from their asset portfolios, thanks in particular to the liberalization of capital flows. 33 As Olivier Passet, Director of Economic Synthesis at Xerfi, points out, this has accentuated the growth in wealth inequalities, through a surge in financial asset prices:

Capital gains […] have been the number 1 source of concentrated wealth effects for the past three decades. […] Above all, we need to question the metabolism of finance, whose profitability is increasingly built on these capital gains. With asset management players increasingly concentrated and influential, “too big to fail”, and central banks whose primary mission is to keep asset prices weightless, at the risk of causing the finance world to tumble.

Find out more

- Pierre-Noël Giraud, The Inequality of the World. Économie du monde contemporain, Gallimard, 2019

- Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press, 2018

- Michael Förster, Odile Rouhban, Céline Thévenot, Inequality in OECD countries: the gap between rich and poor is widening, Après-demain, 2016

- Fifty shades of flexible working in the UK, Le Monde (24/03/2019)

- Martin Anota, At the roots of Trumpism, Reaganomics, blog post, (09/11/2018)

Inequalities in income and pollution are linked

Not all types of pollution are correlated with income

On a global scale, while rich countries emit more greenhouse gases per capita than poor countries, this is not necessarily the case for all types of pollution.

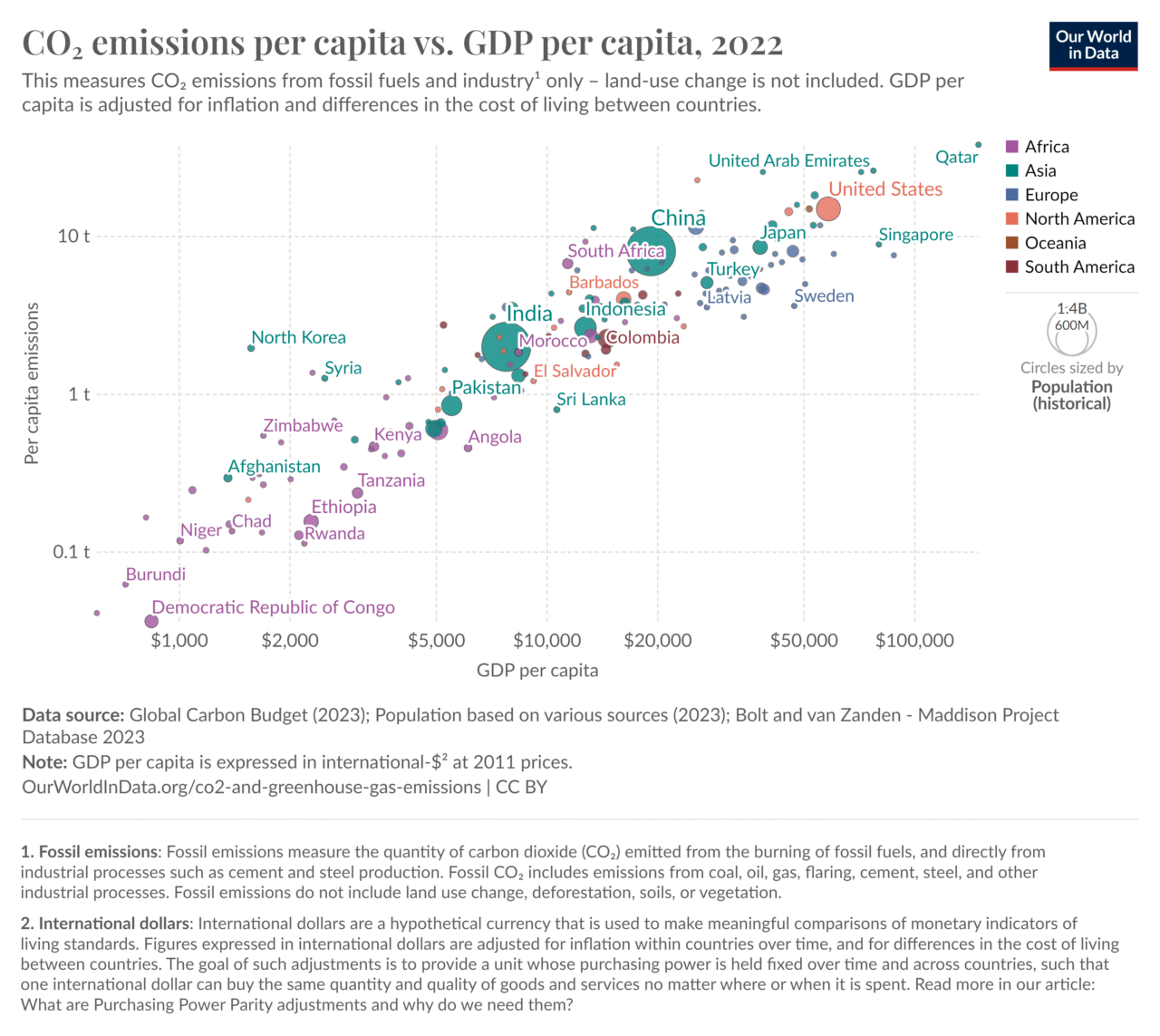

CO2 emissions

As the following graph shows, GDP per capita is strongly correlated with CO2 emissions (excluding deforestation).

CO2 emissions per capita (from fossil fuel combustion) as a function of GDP per capita

Reading: In the USA, in 2022, GDP per capita is around $60,000 and each inhabitant emits an average of 15 tonnes of CO2 per year.

Source Source : CO₂ emissions per capita vs. GDP per capita, Our World in Data, 2024.

This correlation is even more marked if we look not at territorial CO2 emissions, as in the case above, but at the carbon footprint, which measures emissions induced by consumption.34

Material extraction

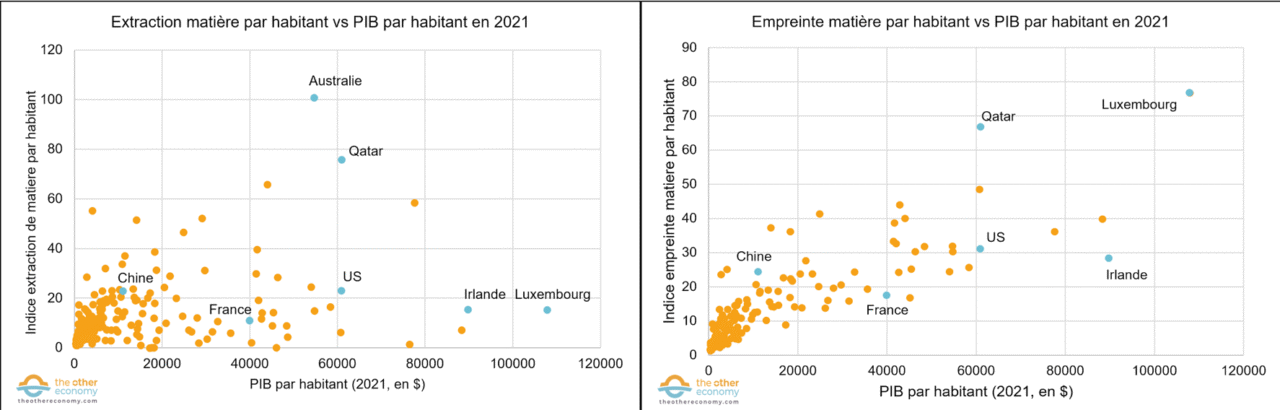

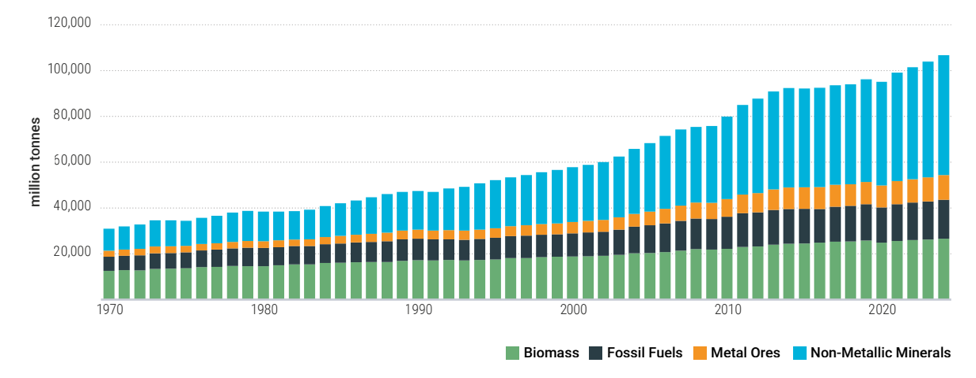

Created in 2007 by UNEP, the International Resource Panel studies the characteristics and impact of the way societies and economies extract, use and dispose of natural resources: biomass (crops, crop residues, grazed biomass, wood and fisheries), fossil fuels, metals and non-metallic minerals (sand, gravel, clay).

As explained in the Global Resources Outlook 2024 report, the extraction, use and end-of-life of natural resources are accompanied by multiple forms of environmental pollution and degradation. Indicators in this field are therefore good approximations of the overall pressure exerted by human activities on the environment.

The domestic extraction indicator measures the materials harvested (agriculture, forestry and fishing) or extracted (mining and quarrying) on a country’s territory. The material footprint indicator, on the other hand, measures all the resources mobilized worldwide to enable a country’s consumption.

The two graphs below show a correlation between the material indicators and GDP per capita, albeit less clear-cut than for CO2 emissions.

It should also be noted that the correlation is more marked for the material footprint indicator than for the extraction indicator. This is quite logical: the countries from which natural resources are extracted are not necessarily those where they are ultimately consumed (whether directly, as in the case of food, or once processed and incorporated into goods). In particular, this means that the people who suffer the negative consequences associated with the extraction of materials (particularly when mining activities are involved) are not always those who benefit from the products made from these materials.

Extraction and material footprint vs GDP per capita in 2021 for all countries in the world.

Reading: France has a GDP per capita of around $40,000 in 2021, a material extraction index of 11 and a material footprint index of 18. The higher the extraction index, the more materials (agriculture, mining, etc.) the country extracts from its territory. The higher the material footprint index, the more resources the country mobilizes globally to ensure its own consumption.

Source Global Material flows Database for material footprint per capita and Our world in data for GDP per capita.

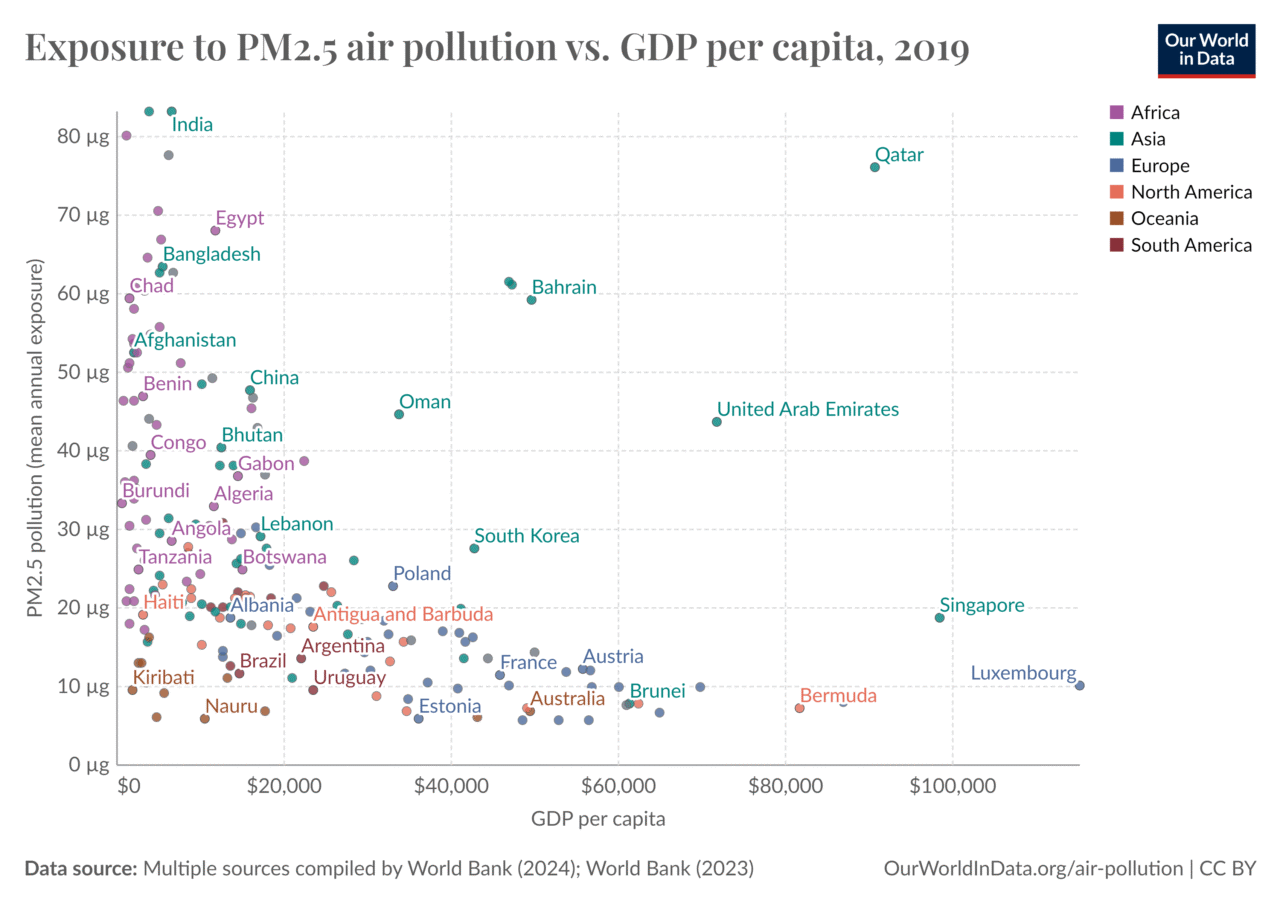

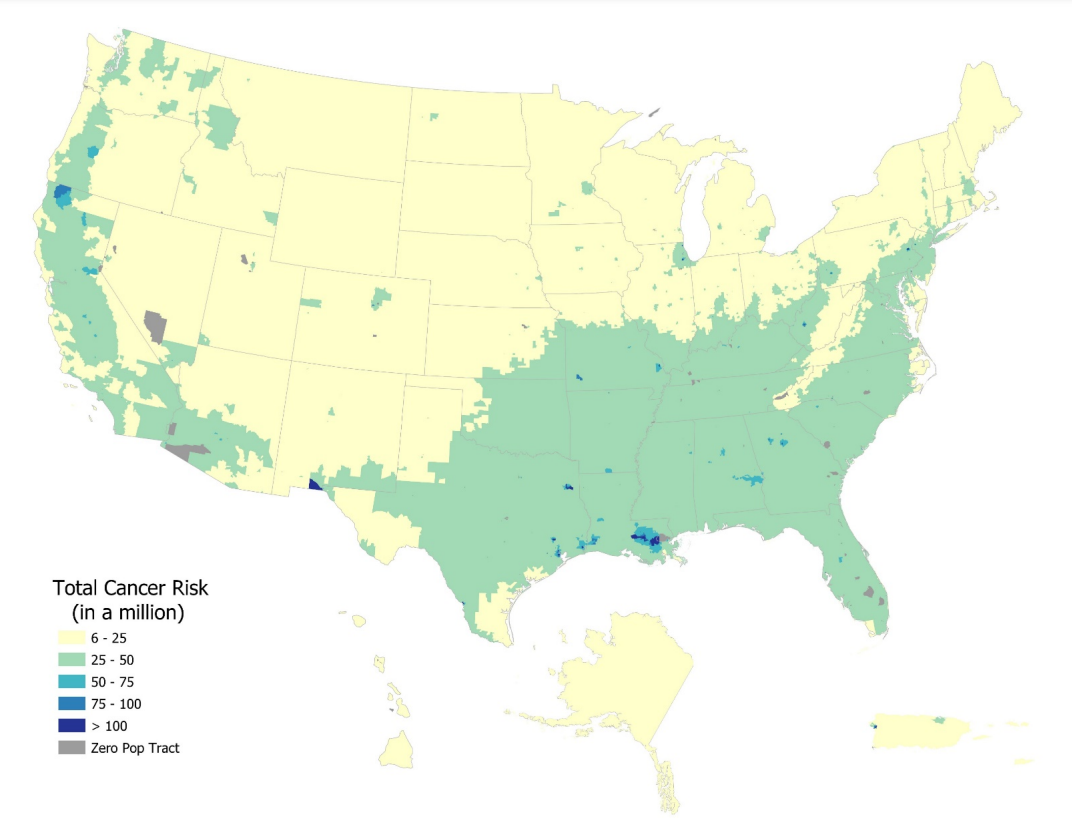

Exposure to local pollutions

Pollutions that happen at a more local level (air, soil, water, plastic, chemical, noise, etc.) are generally lower in wealthier countries.

Indeed, these countries have the means to control emission levels, enforce environmental standards and treat waste. Their inhabitants also have the means to pay higher prices for less polluting goods and services. What’s more, rich countries are often in an economic situation that enables them to relocate polluting production and waste treatment to countries with less stringent standards.

Exposure to fine particle pollution as a function of GDP per capita

Source Exposure to PM2.5 air pollution vs. GDP per capita, 2017, Our World in Data.

Within a given country, greenhouse gas emissions are partly correlated with income.

On a national scale, inequalities in income and wealth obviously have an effect on the distribution of pollution between individuals.

When we consider the carbon footprint of individuals, i.e. the emissions induced by their consumption, 34 inequalities in emissions roughly follow inequalities in income. The higher an individual’s income, the more CO2 he or she emits, and therefore the more unequal a country is in terms of income, the more unequal it is in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

It should be noted, however, that inequalities in CO2 emissions are less marked than inequalities in income. Firstly, wealthier households tend to save a larger proportion of their income, which by definition has no impact on the emissions linked to their consumption. 36

What’s more, the richest households emit proportionally less CO2 when they spend €1, than the poorest households. This is explained by two effects: the structure effect and the quality effect, highlighted by Antonin Pottier, Emmanuel Combet, Jean-Michel Cayla, Simona de Lauretis and Franck Nadaud in a study published in 2020, using INSEE data. 37

The structure effect refers to the fact that the consumption structure changes according to the decile. 38 of household income. Poorer households spend more of their income on CO2-emitting goods (home heating, transport, etc.), while richer households can spend more of their income on low-emission goods and services (i.e., the share of services in consumption increases as individual income rises).

The quality effect refers to the fact that for the same good or service, a wealthy household will be able to consume a proportionally lower-emitting version. For example, making a €4,000 luxury bag doesn’t emit 100 times more CO2 than a €40 bag, but perhaps “just” 10 times more, or even as much. This means that the carbon intensity of consumption by the wealthy classes is lower than that of the working classes.

Antonin Pottier and his colleagues point out that “the standard method for calculating household carbon footprints neglects […] the quality effect. It is possible that the quality effect plays down and that the method thus leads to overestimating the emissions of the wealthiest classes.”

The poorest people obviously don’t choose this situation, but are simply forced to consume gas to heat their homes or fuel to get around, without being able to buy labor-intensive products such as luxury goods.

In addition to income inequalities, geographical location also influences greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Insee explains that emissions generated by private car travel “vary markedly by department: they are low in highly urbanized departments (0.4 tCO2e per adult on average in 2019 in Paris, 0.7 in the inner suburbs, 1.0 in the Rhône), but exceed 1.5 tCO2e per adult in 15 departments, most of which are predominantly rural”. 39

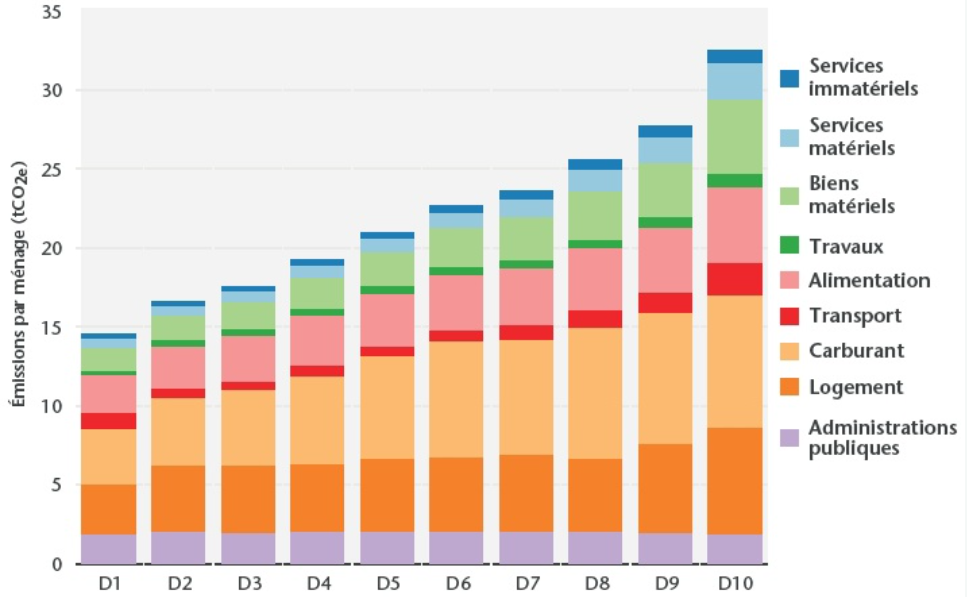

Carbon footprint inequalities in France in 2011 by household: the average view by living standard decile, segmented by consumption item.

Reading: the 10% highest-income households in France in 2011 had a carbon footprint of around 33 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Fuel is their number one CO2 emission per capita (around 10 tCO2e).

Source Antonin Pottier, et al, Who emits CO2? A critical overview of ecological inequalities in France, OFCE Review, 2020.

While there is an 8.8 ratio between the standard of living 40 of households in the last decile 38 and that of the top decile in France in 2011, this ratio is only 2.2 for the level of greenhouse gas emissions. Inequalities in CO2 emissions (in terms of consumption) are therefore more “crushed” than inequalities in income. However, this observation should not obscure the fact that the emissions of the richest are higher in absolute terms, even though they have more financial leeway to reduce them.

Moreover, it’s important to bear in mind that we’re only talking here about inequalities in carbon footprints linked to consumption. In fact, as we explained in Counting GHG emissions, there are different ways of attributing greenhouse gas emissions, reflecting political choices. For example, GHG emissions can be attributed to the shareholders of companies whose direct and indirect activities are a source of emissions.

In this case, inequalities in GHG emissions would broadly follow inequalities in financial wealth (which are far more pronounced than income inequalities). Oxfam, for example, points out that the financial wealth of France’s 63 billionaires is responsible for emitting as much greenhouse gas as that of 50% of the French population. 42 While the methodology is open to debate, the fact remains that this allocation of emissions according to financial wealth makes sense, given that (large) shareholders have real power to influence the transition of the companies whose shares they own, and that they have a priori the choice of investing their savings in other, more virtuous companies.

Find out more

- Antonin Pottier et al, Who emits CO2? A critical overview of ecological inequalities in France, OFCE Review, 2020.

- Global Resources Outlook 2024: Bend the Trend – Pathways to a liveable planet as resource use spikes, United Nations Environment Programme, 2024.

- Interview with Gaël Giraud Pour la planète, l’indispensable réduction des inégalités, CNRS Le journal (21/02/2020).

The concentration of wealth is due to economic and political choices

The increase in inequalities within developed countries since the 1980s – documented in Essentiel 3 – is sometimes presented as the consequence of inescapable economic evolutions, such as globalization shifting part of economic activity to emerging countries, or the development of digital technology creating a “digital divide” to the detriment of the less educated… While these phenomena are very real, it is misleading to abstract them from their political environment. As we detail in this Essentiel with the example of taxation, it is concrete political decisions, which can be revisited, that have led to the current situation.

The role of neoliberal reforms in the 1980s in increasing inequality

The 1970s/80s saw a turning point in the public policies of many countries. The neo-liberal theses of economists such as Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek 43 were gaining in popularity among decision-makers on both the right and the left: the aim was to promote the market economy, remove all constraints on free competition and trade, ensure price stability, and confine the State to the role of guardian of social order and the smooth functioning of markets.

This ideological evolution inspired reforms in many fields, carried out by conservative leaders such as Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom or Ronald Reagan in the United States, but also by social democrats such as Jacques Delors 44 in France.

These reforms, of which the following are just a few examples, have often resulted in increased inequality.

- The promotion ofcentral bank independence from governments and a monetary policy confined to price stability – which deprived governments of one of the fundamental tools of economic policy and still forces them to finance their deficits on the financial markets, making public policies dependent on the judgments of actors with no democratic legitimacy.

- The free movement of capital and the deregulation of finance have led to the financialization of the economy, with its proven negative consequences (financial crises, rising inequalities, shortening of corporate time horizons, abusive widespread consumption on credit), as well as the development of multinationals whose growing powers are excessive.

- The relaxation of labor laws and the reduction of trade union power, which have increased the dynamism of companies but plunged entire segments of the population into precariousness – see the example of the Hartz reforms in Germany. 45 ;

- Strict oversight of budgetary policies with, in the extreme case of the European Union, the adoption of strict rules that focus attention on budgetary calculations at the expense of more vital issues. This is reflected, in particular, in a constant discourse stigmatizing taxes and aiming to reduce public spending, i.e. social benefits and the cost of public services (notably education), and therefore their redistributive effect, described in Essentiel 6;

- The orientation of law and corporate governance towards maximizing profits in order to remunerate shareholders, with damaging consequences in ecological and social terms, and even for the long-term survival of the company itself;

- The development of a race to the bottom in terms of tax, which we develop in the following section.

The race to the bottom fuels inequality

The last three decades have been marked by deleterious tax competition, fuelled by neo-liberal rhetoric that sees taxation as a source of economic inefficiency. This trend has been exacerbated by the development of international tax evasion and tax havens (some of which are located in the heart of the European Union – the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Ireland – or in the United States), exerting downward pressure on governments.

Anti-tax economic theories

What various “economic theories” have in common is that they justify tax cuts (particularly those levied on the wealthiest economic players) on the grounds that they will benefit the economy and society as a whole.

- Taxes cause economic distortions

For neo-liberal economists, the competitive market enables supply and demand to meet, setting prices and thus establishing the value of goods and services, with a view to achieving a situation of equilibrium, a theoretical “social optimum”. 46 . Taxes introduce “distortions” into prices, which no longer reflect production costs alone. They therefore provide “artificial” incentives (in favor of capital or labor, in favor of certain products rather than others) that reduce economic activity (away from the optimum).

Find out more in our supply policy fact sheet.

- The Laffer curve

Drawn on a nape by Arthur Laffer in 1974 47 this curve represents the adage “too much tax kills tax”: when the tax rate rises, companies and workers have less incentive to produce or work, which reduces the tax base. 48 . It is therefore possible that the loss of revenue linked to this reduction is greater than the increase in revenue resulting from the rise in the tax rate.

Find out more in our “Runoff theory” fact sheet.””

- The Ramsey rule

According to this “rule”, formulated by the economist Frank Ramsey in 1927, the optimal tax rate is inversely proportional to the elasticity of the tax base. 49 of taxable income. If we consider that the income declared by the wealthiest is highly elastic (i.e., very sensitive to tax increases), it is inefficient to tax the rich heavily in order to raise taxes, as they would react by hiding their income, moving abroad or working less. According to empirical studies 50 the elasticity of income to taxation is actually quite low, which can be explained by a number of factors: entrepreneurs may have other motivations than financial gain alone; individuals are attached to their country by numerous ties; tax exemption possibilities are not unlimited.

Many governments have reduced the statutory corporate tax rate and the top marginal income tax rate. There has also been a decline in wealth taxes, which were already very low. Lastly, in addition to corporate income tax, the aim is to reduce all compulsory levies on companies (social security contributions and production taxes) in order to ensure their competitiveness, in line with supply-side policies.

A veritable “tax race to the bottom” has thus taken place over the last few decades. While some countries (notably tax havens) are able to take advantage of this situation 51 ), this strategy can only be a losing one overall.

This was underlined by Janet Yellen, US Treasury Secretary, on the day when nearly 140 countries and jurisdictions adopted a global minimum corporate tax.

Today is a historic day for economic diplomacy. For decades, the United States has participated in a counterproductive international tax competition, lowering its corporate tax rates only to see other countries lower theirs in response. The result was a global race to the bottom: who could cut their corporate tax rate further and faster?

No nation has won this race. Lower tax rates have not only failed to attract new business, they have also deprived countries of funding for important investments such as infrastructure, education and anti-pandemic efforts.

Faced with the loss of tax revenues induced by this race to the bottom, as well as by international tax evasion, governments are forced either to increase other taxes (particularly those levied on consumption, such as VAT, and therefore on the population as a whole), or to reduce some of the public spending that has a redistributive effect (social benefits, social policies, funding of public services _seeEssentiel 6). This is a primary cause of increased inequality.

The second reason is the specific nature of the taxes that have been cut the most, and the fact that they mainly concern the wealthiest sections of the population. In fact, the dual dynamic of tax cuts and international tax evasion particularly affects taxes with a base of 48 is relatively mobile (in a context of free movement of capital): the profits of multinational companies, taxes on the income of the most affluent and on wealth.

For example, the people who benefit from lower corporate taxes and tax evasion by multinationals (via dividends or rising share values) are well-to-do, or even very well-to-do: in 2021, only 6.6% of French people – the vast majority of whom are senior executives and self-employed – owned shares. 53 . At the other end of the spectrum, the loss of revenue for governments undermines their ability to implement social policies, and thus to help the most disadvantaged.

– States’ guilty laissez-faire attitude towards tax evasion and tax havens

International tax evasion by wealthy individuals and multinationals consists in playing with the loopholes and asymmetries of different tax systems, in order to place, legally or by fraud, part of their assets and/or income in low-tax countries, without expatriating there. In the early 2020s, the amounts involved were estimated at $350 billion in lost annual tax revenue.

International tax evasion began to develop with the opening up of capital markets in the 1970s and 1980s. Tax havens 54 some of which had existed since the 19th century, came into their own at the heart of the ultra-complex legal and financial structures of offshore finance. Wealthy individuals hid part of their wealth and the income derived from it. Multinationals transfer part of their profits via various schemes that exploit the loopholes in national tax systems. Banks and other financial institutions hide part of their risky activities.

If international tax evasion is not the result of a deliberate policy on the part of governments, it has benefited from the complicity of international finance and a guilty laissez-faire attitude on the part of public authorities for decades. “We mustn’t forget that it was the investment banks who, thanks to globalization, offered tax products in the 1990s, which created these excesses. And the states didn’t coordinate and create an avenue for tax advice.” 55

Find out more in our fact sheet on tax evasion and tax havens.

The emblematic example of corporate income tax

The reduction in the corporate income tax rate is a good example of the concomitance of the two dynamics mentioned above. It is fuelled by :

- On the one hand, there is the argument that low taxation is essential to the competitiveness of national companies, to attracting investment from multinationals, and thus benefiting the entire economy (on this reasoning, see Misconceptions 2 and 3);

- on the other, by the fear of multinationals declaring their profits in other countries with more accommodating tax regimes.56

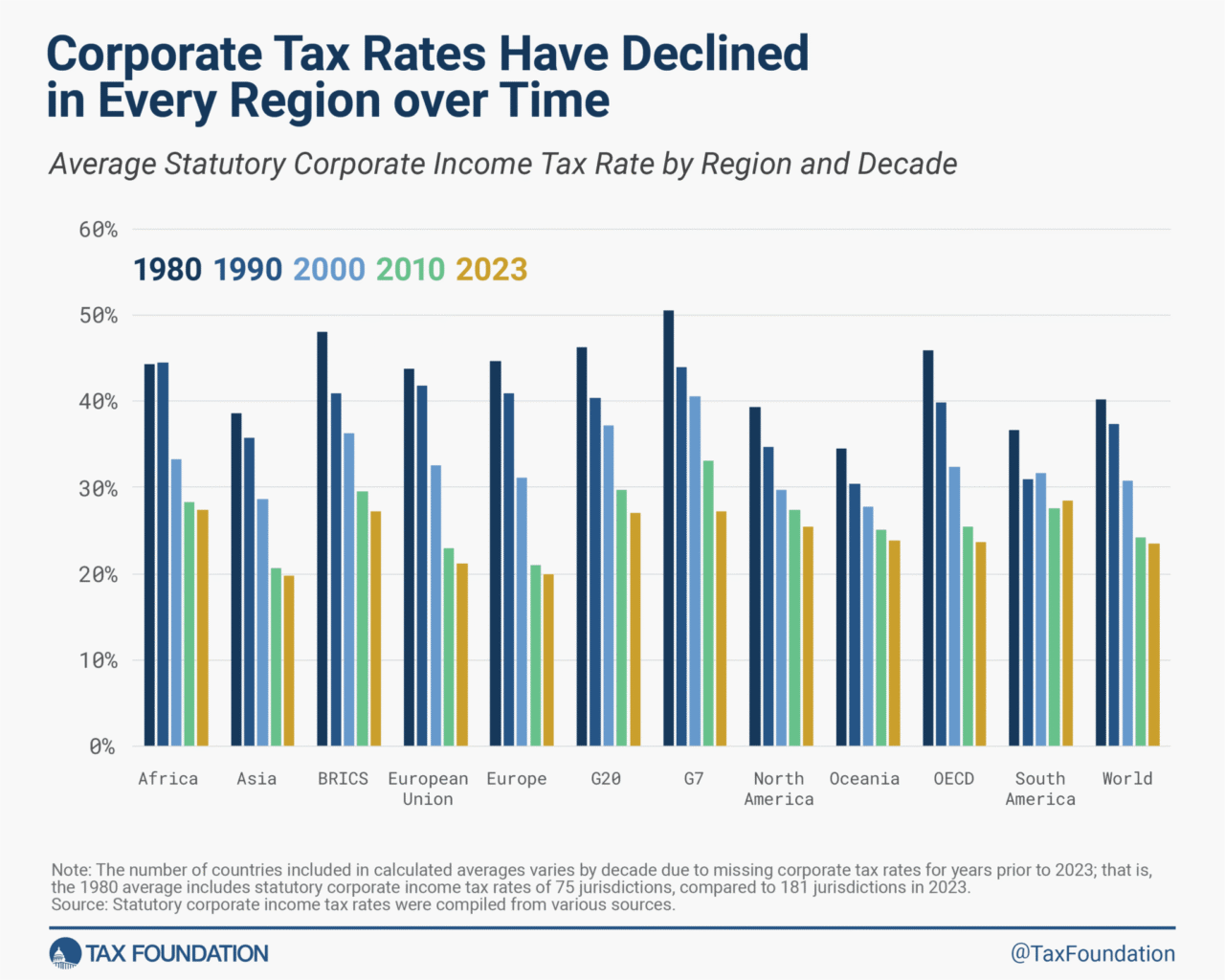

In the United States, the top marginal corporate tax rate was still 50% in the early 1980s; it fell to 38% in 1993, and Donald Trump’s 2017 tax reform endorsed a 21% “flat tax” for all companies. In France, the standard rate has fallen from 50% in 1986 to 25% today; in the UK, the main rate was 50% in 1983 versus 19% in 2022.

Average statutory corporate tax rate by region and decade

Source Corporate Tax Rates around the World, Tax Foundation, 2023

Heritage has always been little taxed

We explain in Essentiel 7 and Idée reçue 6 that the accumulation and transmission of wealth are at the heart of the dynamics of inequality. In essence, these mechanisms are cumulative: wealth (real estate and financial assets) generates income (rents, dividends, etc.), which makes it possible to acquire more assets and pass them on to descendants. Taxation is the main lever for deconcentrating wealth.

Left to its own devices, this mechanism runs the risk of converging towards a rentier society like the Europe of the early 20th century, where 80% of household wealth came from inheritance. Down to 34% in 1970, this figure had risen to 55% in France by 2010. 57 Yet very few political measures have been deployed in recent years to curb this trend.

The wealth tax, which explicitly targets the highest wealth, has existed in only a small number of countries, and was abolished in many European countries in the 1990s. In France, it was replaced by a tax on real estate wealth alone in 2017, considerably reducing its base 48 resulting in an estimated shortfall of 4.5 billion euros by 2022 59 (1% of the national budget). Many countries nevertheless levy taxes on real estate wealth (the taxe foncière in France), but these leave out a large proportion of total wealth. 60

Added to this is the fact that inheritance taxes are low in many Western countries. The effective average rate 61 is around 5-10% in several countries (including France at 4.5%). 62 Some countries (Portugal, Austria, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Norway) have abolished inheritance tax altogether.

Regressive tax systems

The different dynamics outlined above are partly responsible for the regressivity of tax systems: the poorest people devote a higher proportion of their income to taxation than the richest individuals. This is linked to the fact that, in most tax systems, revenue comes mainly from taxes on consumption and earned income. This is how, for example, the OECD showed in 2023 that, in the majority of countries, “taxpayers who earn at least part of their income from dividends have a lower effective tax rate than people earning wages alone.” 63

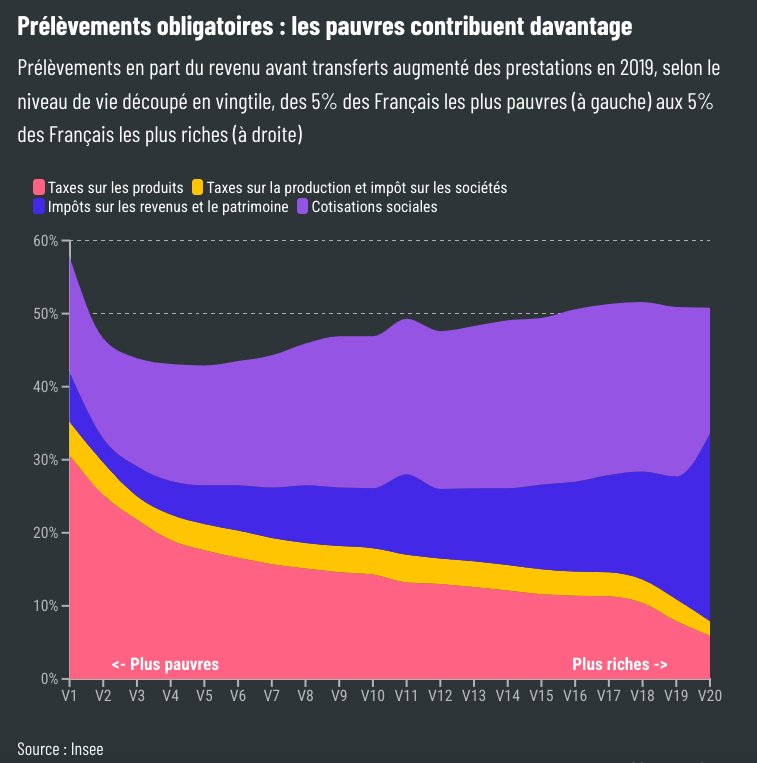

This can be seen by analyzing the French tax system.

This graph shows that the various taxes do not affect all classes of the population in the same way. Taxes on consumption (taxes on products) and social security contributions weigh heavily on the least well-off, whose entire income comes from work and who save very little. On the other side of the spectrum, taxes on capital income and wealth play an important role, but at lower rates.

It should be noted, however, that the regressivity of tax systems can then be corrected by redistribution mechanisms (i.e., the use made of taxes and social contributions). As explained in Essentiel 6, this is the case in France: redistribution mechanisms and public services help reduce inequalities.

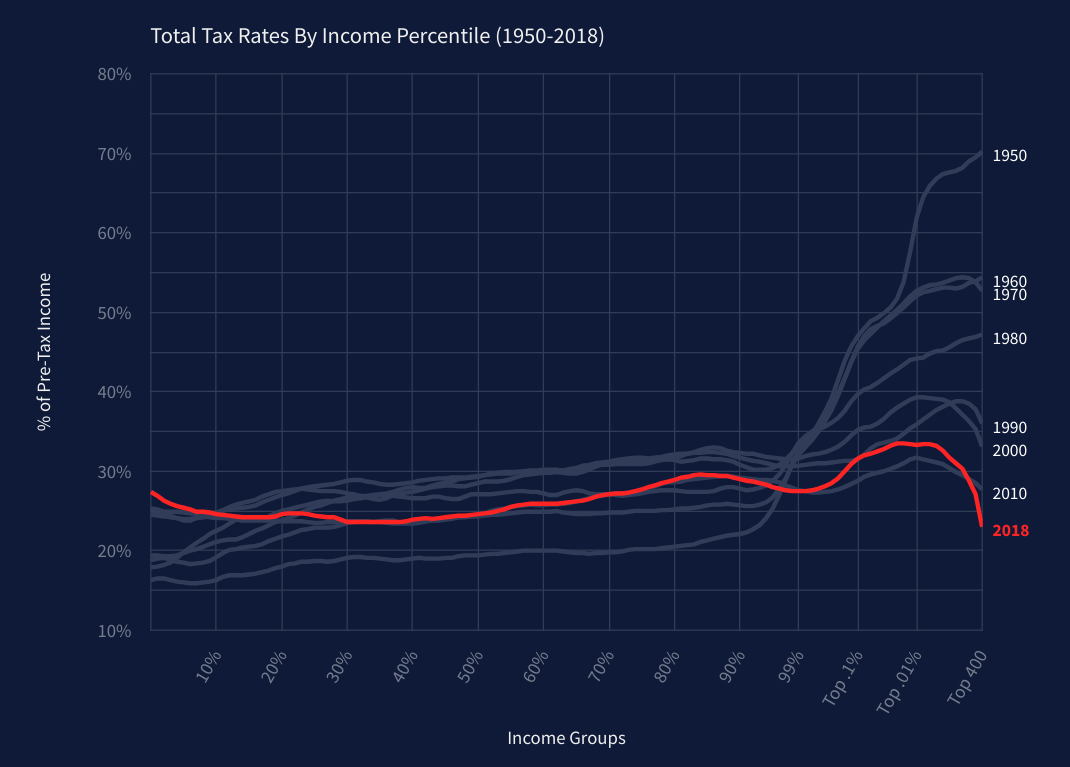

The regressivity of tax systems is even more marked if we focus on the incomes of millionaires. This is what the work of Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman has shown for the United States, for example.

How taxes affect households differently depending on their standard of living

Reading: Standard of living is equal to household disposable income divided by the number of “consumption units” (CU) (1 CU for the first adult in the household, 0.5 CU for other people aged 14 or over, 0.3 CU for children under 14).

Source Budget 2025 Impôts : qui paie quoi?, Alternatives Économiques (18/09/24)

Evolution of the effective tax rate as a percentage of pre-tax income in the United States by population decile and for the 400 highest earners (1950 2018).

Reading: in 1960, the 400 highest earners in the US had an average tax rate of 70%. In 2018 it was around 22.5%.

Source Tax Justice Network Database

Notes

1) Saez and Zucman point out that the top 400 for income coincides (with a few differences) with the top 400 for wealth. 64 This is the Top 400 for both income and wealth.

2) Details of the scope :

All compulsory levies are taken into account: consumption taxes, social security contributions, personal income tax, corporate income tax, property tax, inheritance tax. All taxes are attributed to individuals, even taxes paid by companies (in particular, corporate income tax is attributed to individual owners of shares).

Income includes all national income (measured according to standard national accounting definitions) before taxes and public transfers, and after pension payments. In the same way that corporate taxes are attributed to individuals holding shares in companies, profits are attributed to these same individuals (whether they are then distributed as dividends or retained within the company).

A half-hearted takeover of the tax issue

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 marked the start of the international community taking the tax issue in hand. It highlighted not only the role of tax havens in financial instability, but also the scale of international tax evasion and the extent of its negative consequences. The almost annual tax scandals uncovered by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (Panama Papers, LuxLeaks, etc.) since 2010 have only served to accentuate the legitimacy of this renewed focus.

Under the impetus of the G20, the OECD has launched several initiatives to combat international tax evasion.65

- Put an end to banking secrecy through the automatic and multilateral exchange of banking information, applied by more than 120 countries by 2024 (the United States having implemented a similar initiative as early as 2014 with the FATCA law).

- Adopt international standards to combat tax evasion by multinationals. The OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on the BEPS project has adopted an action plan comprising 15 major types of measures. 66

One of the major successes of the BEPS project has been the adoption, in 2021, of a declaration approved by nearly 140 countries and jurisdictions on the implementation of a minimum 15% corporate income tax worldwide.67

This is a victory for two reasons: firstly, it makes it possible to combat tax evasion by multinationals (by imposing minimum taxation on profits, including those transferred to tax havens), and secondly, it puts a floor under the race to lower tax rates.

These advances have shown that forms of international cooperation previously considered utopian can take place. As the authors of the Global tax evasion report 2024 put it, “tax evasion is not a law of nature, but a political choice”: fatalistic speeches about the impossibility for states to impose overly powerful players in a globalized context are thus put to the test.

Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go before the tax system is restored to its rightful place.

On the one hand, despite real progress, efforts still need to be made in the field of tax evasion by wealthy individuals, due to:

- the limits of the automatic information exchange system (or the circumvention of the rules by certain players);

- the fact that this exchange only concerns financial assets (and not real estate);

- and that billionaires also evade taxes at national level (by holding a substantial proportion of their wealth in shares held by family holding companies, which in many countries, including France, are exempt from tax on dividends).68

On the other hand, as we have seen, international cooperation has focused on the fight against tax evasion: the logic of challenging the legitimacy of compulsory levies in the name of economic efficiency has not been called into question.

Several exemptions 69 have, for example, reduced the scope of the initial agreement on corporate income tax by a minimum of 15%. In particular, they are based on the idea that tax competition is not in itself illegitimate, but only the artificial transfer of profits.

In addition to lower corporate and personal income tax rates, tax competition now takes other forms. The European Tax Observatory 70 highlights the fact that, overthe past 15 years, a growing number of countries have introduced preferential tax regimes to attract high-income earners and wealthy individuals. These regimes target specific professions or income groups perceived as particularly mobile. Above all, since special regimes are mainly aimed at the wealthy, they reduce the progressivity of tax systems, which fuels inequality.

Redistributing wealth reduces inequality

The principle of redistribution is to correct certain inequalities in the name of solidarity. In this section, we limit ourselves to the case of redistribution on a national scale. Redistribution most often takes the form of income or wealth deductions from some people – generally those with the most – which are then shared with the population as a whole – particularly the most vulnerable – in various forms.

Correcting monetary inequalities upstream: wage controls

Distributed income can be controlled by means of a bottom-up (minimum wage) or top-down (maximum wage) wage control mechanism.

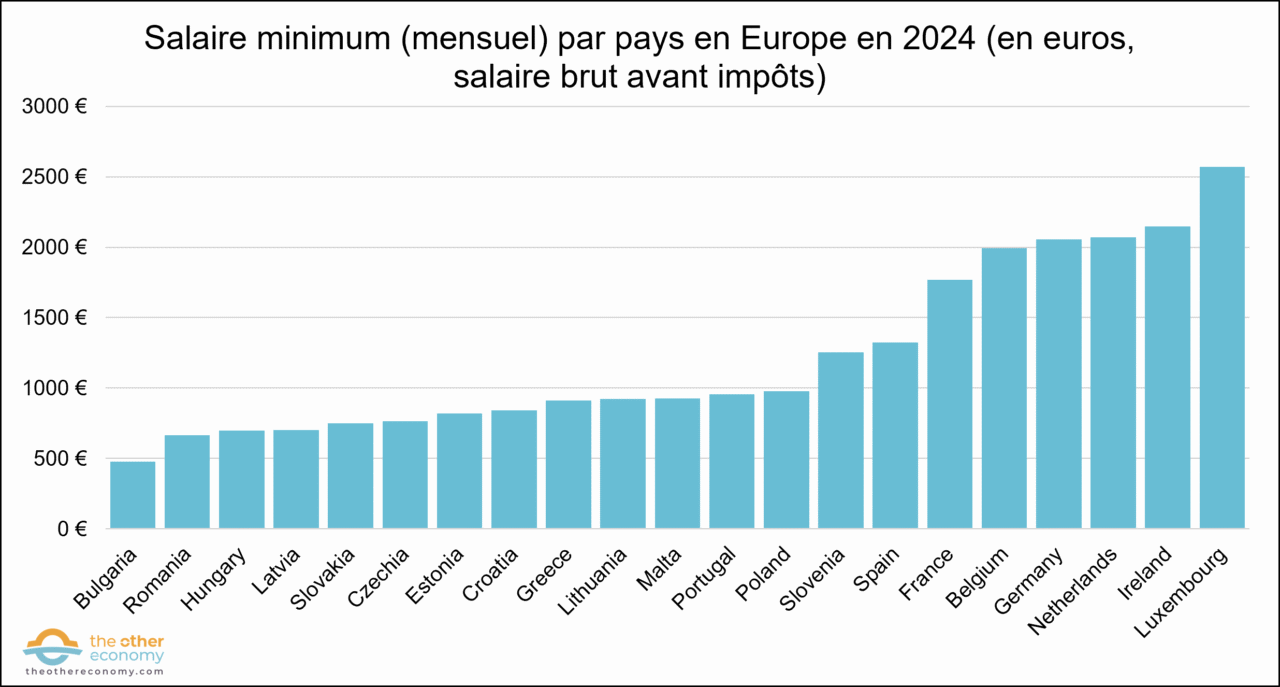

At the start of 2024, 22 of the 27 countries in the European Union (EU) had a national minimum wage. What’s more, in some countries – France, Belgium and Luxembourg – the minimum wage is indexed to price trends, to keep pace with the country’s economic situation. 71 .

The majority of EU member states have set a minimum wage, with significant variations between countries

Reading: in 2024, the gross minimum wage in Bulgaria was 477 euros per month.

Source : Eurostat, January 2024

In the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Sweden, Finland 72 ), there is no national minimum wage. In Sweden, for example, wages are negotiated between employees and companies, giving rise to “collective agreements” in which trade unions play a crucial role. These collective agreements provide a framework for dialogue that generally enables wage negotiations to take place over a given period. However, companies are under no obligation to enter into such exchanges with unions, particularly when the terms negotiated in a collective agreement expire. In 2023, for example, a number of companies refused to re-enter the wage negotiation phase when their collective agreements were due to expire, leading to strikes of a rare scale in Sweden. 73

Minimum wage and living wage

The minimum wage is determined – where it exists – by national legislation. However, this wage does not always guarantee that workers can provide for themselves and their families. The International Labour Organization (ILO) now recognizes the concept of a ” living wage”, defined as the wage that enables a worker to meet his or her own needs and those of his or her family (food, water, housing, education, health, transport and precautionary savings, etc.). 74 ).

Determining a living wage by region/country is a tricky business. THE NGO Fair Wage Network has developed a database on living wages. Based on the work of this NGO, the French group Michelin has, for example, committed itself to guaranteeing a decent wage (including bonuses) for all its employees (in France and internationally) by 2024. 75

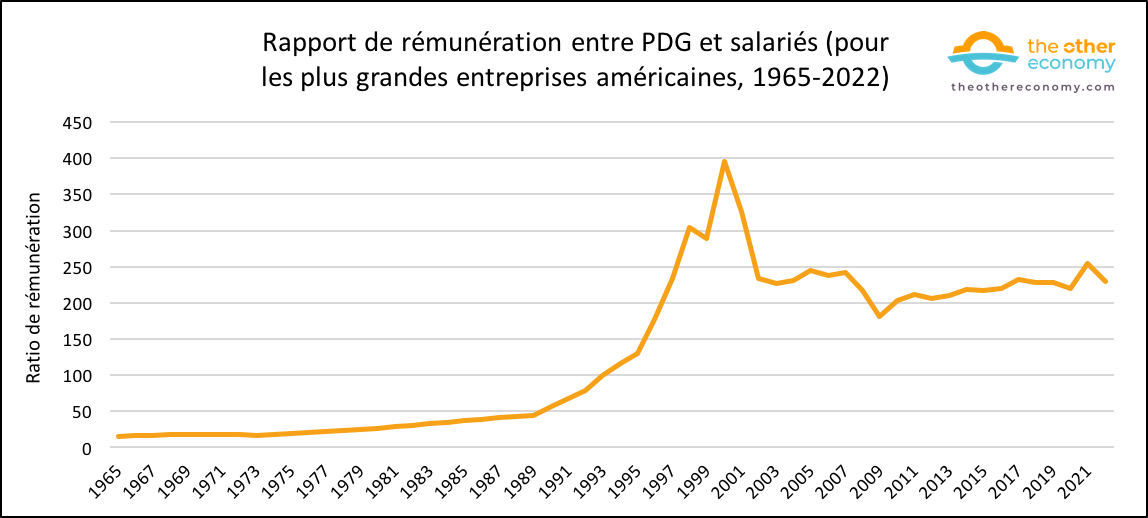

At the other end of the social scale, in order to reduce inequalities, it is possible to introduce a “maximum salary” – as is the case, for example, in French public-sector companies. Note that it is preferable in this case to speak of “maximum remuneration” to include not only the fixed part of the salary, but also the variable part and profit-sharing (stock options, etc.), or even benefits in kind, which are important for the management and top management of companies. Combining minimum salary and maximum remuneration would thus be tantamount to establishing a maximum remuneration differential within a company. 76 As mentioned inEssentiel 8, this proposal has been put forward by certain economists – following the significant increase in the ratio between executive salaries and the minimum wage since the 1980s.

Correcting inequalities downstream: taxes and social benefits

One of the most visible mechanisms of redistribution is that which passes through the following two channels:

- On the one hand, compulsory deductions (taxes and social security contributions) – and their more or less progressive nature;

- on the other hand, redistribution in the form of social benefits – the latter giving citizens the assurance that they will be able to cope with life’s various risks (having a pension, having replacement income in the event of illness, maternity, loss of work, etc.).

In this section, we focus on the French case.

More or less progressive compulsory levies

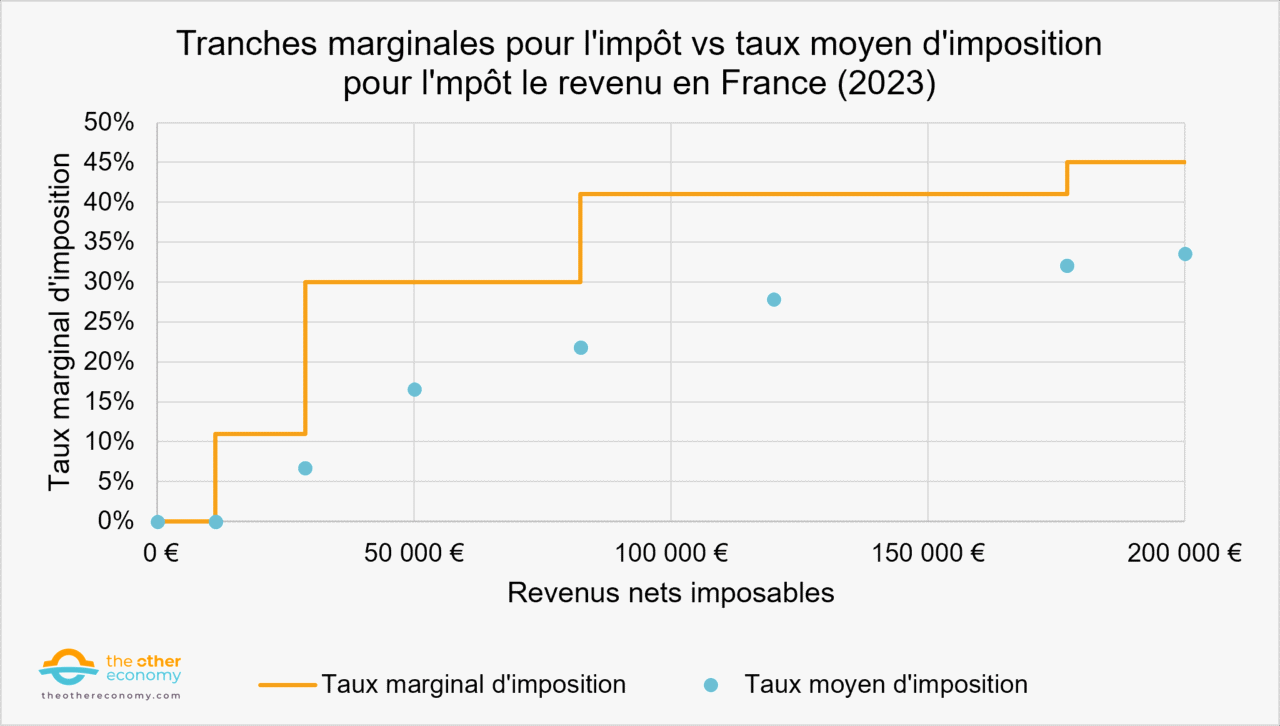

The different types of compulsory levies 77 have more or less redistributive effects, depending on the type of tax base and levy method.

In France, all individuals pay VAT, which is applied to all consumer goods. It is said to be “regressive” insofar as the poorest people pay a higher proportion of their income (see Essentiel 8). On the other hand, not everyone pays income tax. In principle, income tax is progressive: the higher a household’s income, the higher the tax rate (up to a certain threshold), and the more modest households are exempt.

The various levies (taxes and contributions) contribute to different degrees to the financing of the State.

[In France] 44% of households pay income tax. […] People emphasize income tax, but in fact it brings in less than the CSG (Contribution Sociale Généralisée), and much less than VAT. […] We all pay the CSG, we all pay the VAT, so we all make a very substantial contribution to public finances.

Redistribution through social benefits and public services

Part of the compulsory deductions (in particular social security contributions, but also certain taxes such as the CSG) is then redistributed directly to citizens. This is done in particular through the payment of social benefits, which include family allowances, housing subsidies and so on.

The aim of these benefits is to pool risks and promote solidarity between different categories of population: from working people to retired people, from healthy people to sick people, from those who have a job to those who don’t, from people without young children to families, and so on.

In France, in 2017, these various social benefits enabled an 8-point reduction in the poverty rate (14.1% of the metropolitan population living below the poverty line, compared with 22.1% before redistribution). 78

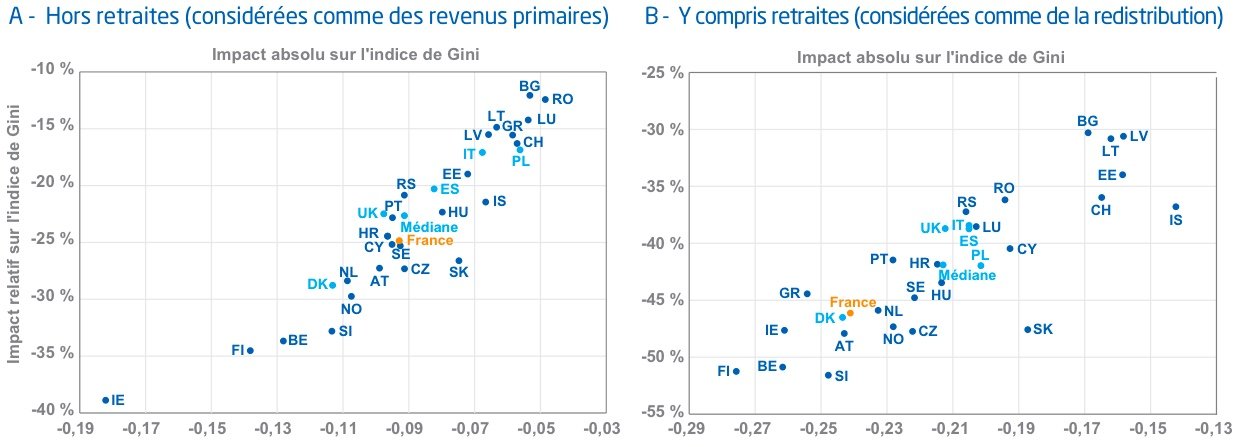

The graphs below show the role of redistribution through tax and benefit payments in various European countries.

Reading: In France, the Gini coefficient 19 for household income is reduced by 0.093 points, or 24.8%, by redistribution excluding pensions. The closer a country is to the bottom-left corner, the greater its redistribution.

Source Inégalités primaires, redistribution: comment la France se situe en Europe, France Stratégie, 2020.

The Gini coefficient 19 is lowered by almost 23% thanks to Europe-wide redistribution mechanisms – France being characterized by a slightly higher impact of redistribution than its European neighbors (left graph).

It should be noted that there are major methodological issues at stake in these discussions and estimates: which compulsory deductions or social benefits should be taken into account? In other words, what perimeter should be considered when talking about redistribution? The impact of redistribution can vary according to the scope of the study. For example, in the chart on the right, pensions are included in social benefits, which means that the impact of redistribution on reducing inequality is much greater than in the chart on the left.

The evolution of redistribution – a historical perspective

Redistribution mechanisms were profoundly altered at the beginning of the 20th century with the introduction of progressive taxation: the higher a household’s income, the more it is taxed (in relative terms).

According to economist Thomas Piketty 81 this has had two significant consequences in Europe and the United States: on the one hand, a “static” impact, by reducing income inequalities at a given point in time; on the other, a “dynamic” impact on inequalities, by preventing too great a concentration of wealth – in association with the introduction of capital taxes.

For example, in France in the 1920s and 1930s, the top 1% of households earned around 20% of national income, compared with 7-8% in the early 1990s. Since the 1980s, the trend in developed countries has been towards lower taxation of very high incomes, and lower taxation of capital (see Essentiel 5).

Worldwide 82 Western Europe remains the most redistributive region, while Latin America and Africa are among the least redistributive.

Public services: another facet of redistribution

Another dimension of redistribution – which may seem less direct, but is no less essential – is found in public services. In fact, redistribution takes place not only at the level of individuals or households, but also through public services, financed by taxes, guaranteeing everyone, regardless of income, a supply of essential goods and services.

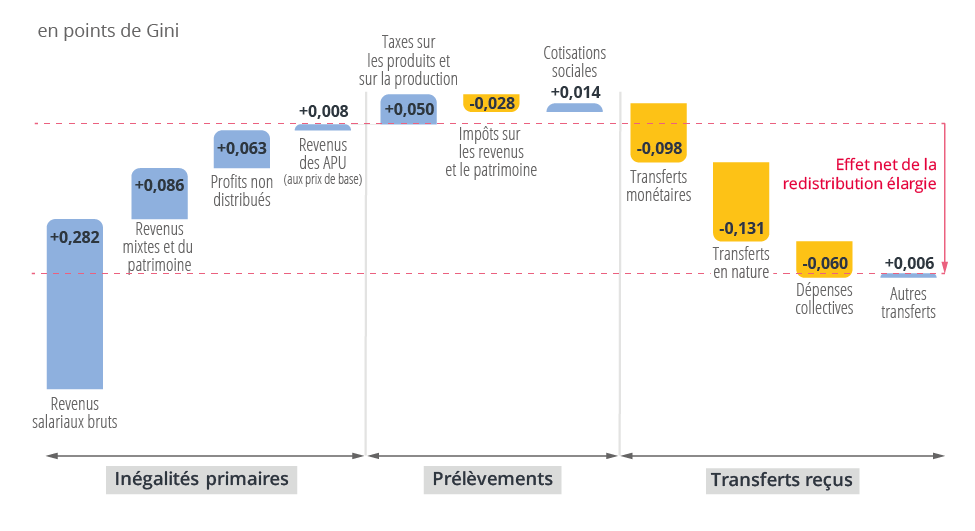

Insee refers to “extended redistribution” when it includes public services in the notion of redistribution. 83 – which leads to much higher redistributed sums. In an analysis published in 2023, Insee shows that more than one French person in two is a net beneficiary of extended redistribution.

[I]n 2019, [in France,] 57% of people receive more than they pay in. This share of people net beneficiaries of extended redistribution rises to 49% around the median standard of living, compared with over 85% among the lowest 30% and 13% among the wealthiest 5%. Before transfers, well-off households have an income 18 times higher than that of poor households, compared with 1 to 3 times higher after transfers.

Taking into account public services – notably health and education spending – redistribution divides the scale of inequality in France by 6. 84 Unsurprisingly, the most modest are the main beneficiaries, but it should be noted that some of the wealthiest are also net recipients (notably because of healthcare spending).

Extended redistribution also favors single-parent families, couples with three children and women, but is rather neutral for white-collar and blue-collar workers.

The breakdown of France’s Gini coefficient below highlights the net effect of wider redistribution. As mentioned in Essentiel 5, taxes on consumption and social contributions (VAT, CSG, etc.) tend to amplify inequalities. This is not entirely offset by the progressivity of income and wealth taxes. However, when social benefits (monetary transfers) and public services are taken into account, redistribution enables a significant reduction in the Gini coefficient, over 50% of which is explained by transfers in kind, which include spending on health and education, as well as pensions.

Reading: Social contributions have a slightly unequal effect in France in 2019 – by increasing the Gini coefficient 19 by 0.014 points.

Source Insee, La redistribution élargie, incluant l’ensemble des transferts monétaires et les services publics, améliore le niveau de vie de 57 % des personnes, Mathias André, Jean-Marc Germain, Michaël Sicsic, 2023

Efficiency and acceptability of redistribution tools

The different means of redistribution we have just seen are not equal in terms of their impact on inequality. What’s more, some may be more difficult to implement than others.

For example, in a note from 2023 86 the Conseil des prélèvements obligatoires (CPO) underlines the effectiveness of targeted cash transfers compared to a reduction in VAT to support the poorest households.

It is, however, important to analyze VAT over its entire lifecycle, even if its “regressive” nature makes it difficult to assess its impact. 87 is not in doubt. The CPO note stresses the importance of analyzing the socio-fiscal system in its entirety: VAT is, in fact, a major source of revenue for the State, enabling it to set up targeted monetary transfers to the most modest households and, above all, transfers in kind (education, health) which, in absolute terms, benefit low-income households more. 88

Starting with the situation in 2023, a simulation is carried out to compare the effectiveness of different support measures, in particular comparing the VAT cut with targeted cash transfers. The CPO draws the following conclusions:

The progressive nature of the French social and fiscal system is based on social benefits and cash transfers rather than taxation. VAT also contributes to the progressiveness of the social and fiscal system by financing social transfers and national and local public services. […] A reduction in VAT is not effective in supporting the purchasing power of the most modest and middle-class households, since it benefits the wealthiest households to a greater extent, and a large part of this reduction is captured by companies.

Redistribution via public services, and access to healthcare for example, is a silent form of redistribution. On the other hand, targeted and direct cash transfers, however effective, can give rise to “stigmatization” processes, or fuel talk of “handouts”(see Essentiel 7 on the perception of inequalities). These processes have very real repercussions and must be taken into account: they explain, in particular, the high level of non-use of social benefits in France, as highlighted by the Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (Drees) in 2022. 89

For redistribution to be effective, on the one hand, we need to be able to levy fairly (i.e., generally through progressive taxation, which is not always the case in practice), and on the other hand, we need to be able to ensure that the tax we pay is fair. 90 ). On the other hand, we need to target those households most in need. This may be those with the lowest incomes, but not necessarily, for example in cases where the state wishes to target disadvantaged single-parent families.

In addition, the design of a socio-tax system is, in itself, complex, and the superimposition of schemes (social benefits, exemptions, etc.) can undermine the progressiveness of the socio-tax system, notably through threshold effects. 91

The issue of threshold effects thus raises the question of the precise targeting of each redistribution policy. In France, for example, during the health crisis of 2020 and the period of high inflation in 2022 and 2023, the lowest 10-20% of income earners were protected by direct transfers and the indexation of the SMIC (minimum wage) to inflation. However, this has not been the case for households slightly below the median income, who, according to an OFCE study covering the period 2021-2023, had the lowest income growth over these two years, fuelling a feeling of “social downgrading” on the part of the middle classes. 92

Find out more

- Primary inequalities, redistribution: where France stands in Europe, France Stratégie, 2020

- François Bourguignon, Sharing the Wealth, IMF, 2018

- Thomas Piketty, A Brief History of Equality, Ed. Seuil, 2021

- Marion Cohen, Alain Grandjean, La France championne des dépenses publiques : comment fausser un débat, Chroniques de l’anthropocène, 2019

A distorted perception of inequality

In order to develop political solutions to growing inequalities, and to find public support for these solutions, it is first necessary to establish a common understanding of the phenomenon. As it turns out, inequalities are difficult to perceive and analyze, for a number of technical and psychological reasons

Economic inequalities are complex to apprehend: distinction between wealth and income

A first factor that complicates the perception of inequalities is their multidimensional nature. In Essentiel 1, we explained that inequalities are not limited to monetary aspects: inequalities in access to education and discrimination profoundly affect the lives and trajectories of individuals, even when placed in comparable economic conditions.

Moreover, wealth inequalities themselves need to be read on several levels. A notable example is the distinction to be made between income and wealth inequalities 93 because the mechanisms governing these two forms of wealth are quite different:

- Income from work (wages or self-employed remuneration) is a socially regulated flow (whether regulated by a minimum wage or through hiring standards such as company pay scales), relatively homogeneous within a given profession, and non-heritable.

- Wealth, on the other hand, is a stock (the totality of an individual’s physical and financial possessions): it is highly dependent on the family context, and in particular on inheritance – see Misconception no. 6.

As we explain in Essentiel 5, it is also based on a dynamic of accumulation, with the result that, throughout the world, wealth is far more concentrated than income.

In France, for example, in the early 2020s, the top 10% of income earners will receive 24% of national income before redistribution, while the top 10% of wealthy individuals will own 47% of the country’s assets. 94 On a global scale, the top 10% of earners receive 50% of income; those with wealth in excess of $100,000 hold 82% of wealth. 95 In both cases, the bottom 50% of the population own virtually nothing: 8% of wealth in France and 2% worldwide.

This distinction is not insignificant: it’s not just about the extra income inequality generated by wealth income.

Indeed, inequalities linked to wealth itself can have very specific effects on individuals’ career paths. Entering adulthood with capital provided by one’s parents means being able to pursue higher education without having to work to finance it, which has a major impact on success (probably several dozen percentage points in exam passes). 96 early access to home ownership 97 and avoid the cost of rent and the anxiety associated with financing a home; it means having a safety net that allows you to take time to discover yourself, choose a career that matches your aspirations, and take risks.

Young people from disadvantaged backgrounds make more conservative career choices than their wealthier counterparts. 98 At the other end of the spectrum, the rate of business start-ups rises sharply with the level of capital. 99 (doubling from one end of the wealth distribution to the other).

In short, to properly understand the effect of monetary inequalities on individuals, it’s not enough to compare their pay slips: we need to take into account their social environment, as well as the consequences (practical, psychological, etc.) they have on their lives.

Inequalities are distorted by our cognitive biases

Beyond the difficulty of interpreting figures, we need to look at how people perceive inequality in qualitative terms. A number of studies have shown that individuals misjudge the actual distribution of wealth. They highlight the psychological biases that explain this error, and the difficulty of correcting it.

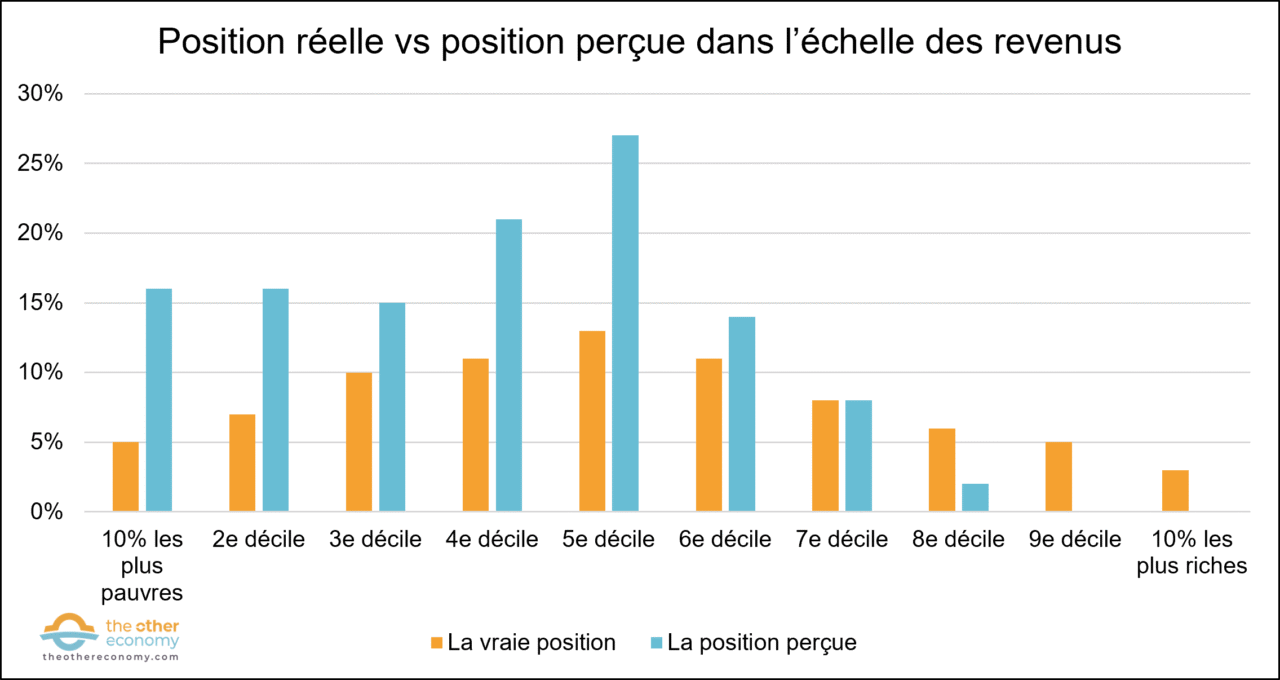

According to a DREES study published in 2022, the French misjudge their position on the income scale: most consider themselves to be average, even when they occupy an extreme position. The effect is spectacular for high-income earners: 14% of the panel surveyed belonged to the wealthiest third of the population, but only 2% were aware of it. And none of them thought they were in the top 10%.

Reading: 13% of the sample is in the 5th decile 38 of the income distribution and 27% of the sample think they are in this fifth decile. This reflects the fact that people believe themselves to be more “average” than they actually are.

Source DREES, L’opinion des Français sur les inégalités reflète-t-elle leur position sur l’échelle des revenus, Études et Résultats, 2022

A 2013 study 101 proposes an explanation for this phenomenon: respondents would evaluate their wealth primarily in relation to their immediate environment, particularly their geographical environment. This is a typical example of the cognitive bias of representativeness: individuals consider by default that their observations (in this case, their socio-economic environment) are representative of the overall population. The lack of social mix thus has the effect of masking the extent of inequalities for all categories of the population, rich and poor alike.

Another psychological bias could have serious consequences for our understanding of inequality: the distorted perception of large numbers.

Some political activists have tried to translate the great fortunes on scales that we have mastered, in order to shock our perception. For example, comedian Pierre-Emmanuel Barré has calculated 102 that if the oldest known hominid, the 3.2 million-year-old australopithecus Lucy, had earned today’s minimum wage and spent nothing from her time to the present day, she wouldn’t be half as wealthy as Bernard Arnault today! In the same way, various websites and pages offer graphical representations of great fortunes, comparing them with more familiar sums of money. 103

The surprise generated by these conversions is significant: it indicates that we fail to give concrete meaning to amounts of millions or billions of euros. Here again, cognitive science research offers an explanation for this phenomenon: our sense of numbers is mainly relative 104 and we put roughly the same psychological distance between, on the one hand, 1,000 euros and a million euros, and, on the other, a million and a billion euros.

When it comes to the economy and inequality, our intuition is often a poor guide, as the quantities involved literally defy our imagination and everyday perceptions.

Perception of redistribution

The issue of inequality is inextricably linked to that of redistribution. In addition to being a risk-sharing mechanism, as discussed in Essentiel 6, redistribution has an economic justification: the economic “game” contains amplifying and cumulative mechanisms. 105 which cause individuals’ fortunes to diverge, all other things being equal. This is intuitively expressed by the popular expressions “Money works for you”, “You only lend to the rich” and so on. Redistribution partially offsets these effects.

Even so, various redistribution schemes (progressive taxation, minimum social benefits, etc.) have historically been contested by large sections of the population, and their application or amounts are regularly the subject of debate. There are two types of cause for this rejection: some have to do with values, others with perception.

Let’s take a look at the main value-based criticisms:

- Redistribution would hinder and discourage free enterprise: why should the community appropriate the wealth generated by an individual’s efforts and ingenuity?

- Redistribution (often referred to as “handouts”) would run counter to individual responsibility: everyone would have to earn their living through their own work, and climb the social ladder if they wanted to increase their income.

- The arguments of “social Darwinism 106 which have been politically influential in the past and are still influential in some countries, such as the United States, argue that it is legitimate for the “gifted” to drain wealth and use it to develop society in their own image, even if it means leaving the “incompetent” in misery.

These judgments are based on widely debatable assumptions, which we examine in Misconceptions 6 (on meritocracy) and 8 (on equal opportunities).

They can also be opposed by value-based arguments: as noted above, wealth tends to be self-sustaining, which can be seen as unfair, since it is independent of any notion of merit or effort. As we can see, there is a conflict between contradictory values, which can only be resolved through political debate(see Essentiel 8).

Other criticisms are based on a misperception of the amounts collected and distributed to the various players. For example, the French tax system, a heterogeneous historical construction, is difficult to understand. Citizens are unaware of their own total rate of compulsory deductions (direct taxes, indirect taxes such as VAT and social security contributions) – and a fortiori of the rates paid by others.

For example, the fact that the top 1% of income earners are proportionally less taxed than the rest of the population is little known to the general public(see Essentiel 5).

The total amount of redistribution is also subject to misinterpretation, not least because of the rhetorical trick of publishing absolute rather than relative figures: social minima, for example, are more readily presented in euros (30 billion in 2023 107 ) rather than as a proportion of public spending (2.1%).

Inheritance tax: a heated debate based on poor estimates

Misperceptions about the numbers involved are also affecting the public debate on inheritance. A 2022 survey 108 and a 2018 CREDOC study 109 attest to both a rejection of inheritance tax and a great ignorance of the system. Respondents fail to answer binary questions such as the existence of inheritance tax for married or civil union spouses, underestimate the value of high assets, and greatly overestimate the amount of tax paid in the direct line, i.e. from parents or grandparents to children (estimated at 22% on average, when the actual average value is less than 5%).

This latter bias could be due to the existence of substantial fees for indirect line inheritances (60%): all it takes is one such example of an “over-taxed” inheritance in an individual’s entourage to provoke a strong emotion and make him reject the whole system, even without knowing about it.

Finally, values also play an important role in perceptions: over 80% of French people prefer the proposition “Inheritance tax should be reduced, because parents should be allowed to pass on as much wealth as possible to their children “s to the following: “Inheritance tax should be increased, because inheritance sustains social inequality”. Family – and work – values are thus deemed more important than the justice of the social system.

Social security fraud is another example of the poor estimation of figures, which skews people’s opinions and is readily exploited in political discourse. The French overestimate it, focusing on examples drawn from their own experience or from the media, whereas the proportion of fraudsters observed during checks by social organizations is very low – 1% for the Family branch of the CAF in 2022. 110 3% for the RSA in 2009.note110

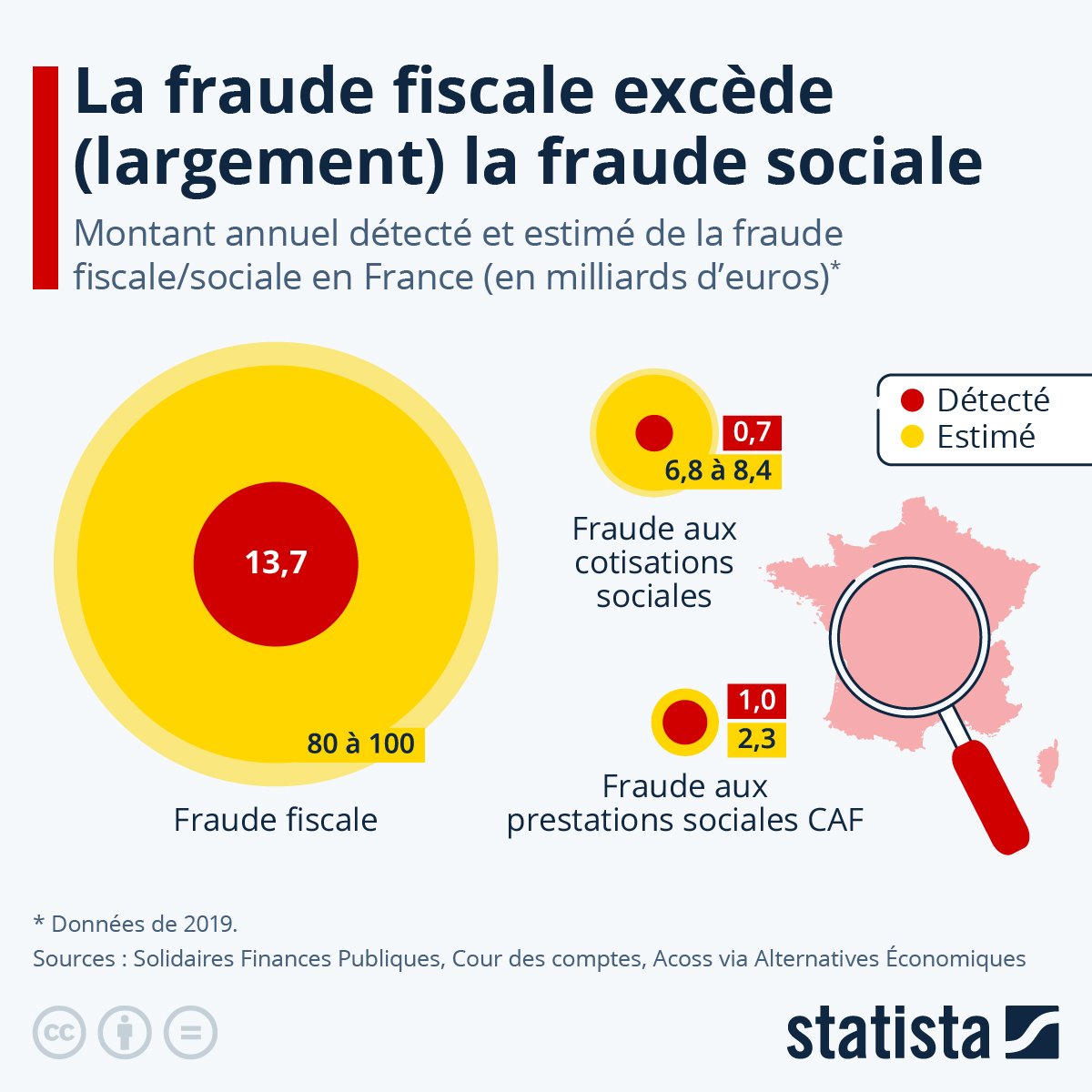

This can be seen as an availability bias: people prefer and overestimate facts that are salient in their memory, particularly when they are stereotyped. It is therefore instructive to compare the amounts of this so-called “social” fraud (fraud on social benefits) with those of tax fraud: several estimates from various institutions conclude that the latter costs public finances 10 times more than the former (around 100 billion versus 10 billion in 2019).

Annual detected and estimated amounts of tax and social security fraud in France (in billions of euros)

Reading: in 2019, in France, detected tax fraud amounted to 13.7 billion euros, while social security contribution fraud was estimated at 0.7 billion euros. The total amounts of these frauds are estimated, respectively, at 80-100 billion euros for tax fraud and 6.8-8.4 billion euros for social security fraud (a ratio of 10).

Source How much tax and social security fraud is actually detected, Statista, 2024

Find out more