This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The great German inflation of 1923 left a lasting impression on people’s consciences, imprinting images such as the wheelbarrows of banknotes needed to buy a single postage stamp. If this exceptional period was fraught with consequences, it also gave rise to a number of preconceived ideas that are worth revisiting, the first of which is undoubtedly that this hyperinflation was due exclusively to the activation of the “printing press”, i.e. the creation of paper money by the central bank. Here, we take a look at the history of this major episode in Western economic life, and draw a few lessons from it.

The origins of the Weimar crisis

At the end of the “Great War” of 1914-1918, Germany was declared defeated and the imperial political system had collapsed. Two days before the armistice, the Socialists seized power and gave birth to the fragile Weimar Republic, caught between the revolutionaries in favor of a socialist republic and the Social Democrats allied with the army. The regime pursued a progressive social policy – the eight-hour day, social insurance, recognition of trade unions, etc. – but failed to bridge the gap between the socialists and the democrats. – but was unable to offset a chronic public deficit, which averaged around 15% of national income between 1919 and 1924 1 .

In 1919, the German economy was in a sorry state. Its productive apparatus had been partly destroyed, and productivity had declined accordingly. Agricultural production was also reduced. In principle, it also had to pay a “war debt” (i.e. the amount of reparations demanded in the Treaty of Versailles) of some 130 billion marks.

In France in particular, it is assumed that “Germany will pay”. It will indeed pay – in the order of two billion marks a year in cash and the equivalent of five billion marks in kind. Paying these reparations will be a major problem over the period: the German state budget is constantly in deficit, the country is unable to borrow abroad, and the central bank’s gold reserves are around two billion marks. Unable to finance itself through large-scale institutional borrowing, Germany was forced to turn to the financial markets, which at the time were totally unregulated.

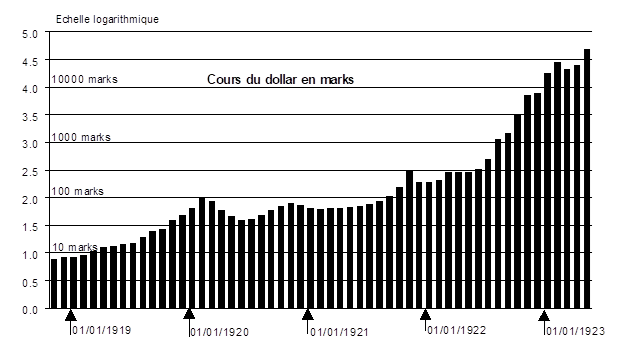

The value of the mark fluctuated according to the expectations of financial players and the behavior of speculators. After the Great War, these expectations were repeatedly upset, on the one hand by the German trade deficit, and on the other by a number of major political events. Overall, the exchange rate of the mark tended to fall sharply from 1919 to 1923, although there were periods of remission when there was talk of a moratorium on reparations or foreign loans to Germany. This situation weakened the German currency to the point where its citizens lost all confidence in it, leading to an inflationary spiral: the country entered hyperinflation from the second half of 1922, following France’s refusal to lend to Germany.

But let’s take a closer look at the sequence of events.

From the armistice to February 1920: rising prices sustained by imported inflation

Immediately after the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, the German outlook darkened. Already high, annual inflation for the period July 1919-February 1920 was around 400%.

Estimates available for early 1920 3 show that wholesale prices rose twice as fast as the cost of living compared to 1913. This is due to the fact that wholesale prices are strongly influenced by import prices, which are clearly on the rise. At the same time, domestic income was reduced to 80% of its 1913 level. Wage rises more or less kept pace with price rises, which were quite strong. The price index was 300 in July 1919, compared with a base of 100 in 1913, and around 200 in the United States and the United Kingdom. All these indicators support the hypothesis that inflation is mainly due to the rising cost of imports.

The weakness of the mark meant that imported goods – around a quarter of national income in 1919 – were paid for at higher prices, pushing up national wages, which were indexed to prices at the time. The German central bank was forced to increase the money supply in order to maintain the volume of transactions and prevent the real economy from suffocating. All the more so as the Deutschmark continued to fall against other currencies, thus sustaining the phenomenon of imported inflation.

Inflation was also high elsewhere. From the end of 1919, the United States, the United Kingdom, Holland, Switzerland and Sweden took measures to restrict monetary policy, which led to a fall in national revenues from 1920 onwards. Denmark, Norway and France, on the other hand, allowed their public deficits to soar, thus financing reconstruction until 1926. In Germany, too, the government favored economic expansion wherever possible.

February 1920 to May 1921: the situation improves

During this period, Germany’s economy recovered and its trade balance approached equilibrium. Public finances improved greatly. The exchange rate of the dollar to the Deutschmark fell dramatically until June 1920, putting the brakes on rising prices and wages, which stabilized from September 1920 onwards. By 1921, the favorable environment enabled the government to finance its deficit with non-monetized Treasury bills, thus minimizing money creation. It should be noted that domestic income growth was around 5% in 1920, giving the public authorities greater room for manoeuvre.

May 1921 to July 1922: intransigence on reparations worsens the situation

This trend did not continue from May 1921 to July 1922, primarily because of the level of reparations and the ultimatum from London: the British government demanded that Germany pay its reparations under threat of occupation of the Ruhr by the Allies. Germany complied, but the burden in question finally worried speculators: the mark plunged. What’s more, the recession abroad weighed on exports, and the balance of trade deteriorated. The rise in the cost of living resumed at a high rate, with wages following suit with a slight delay.

From 1919 onwards, the onset of inflation had caused Germans to start shunning money: they avoided keeping cash on hand, thus moderating the rise in the money supply. When the outlook improved at the beginning of 1920, economic agents’ cash balances (the money they held in cash or bank accounts) rose until May 1921. But by the end of that year, and especially in the first half of 1922, mistrust of the currency increased sharply. The value of the mark in gold plummeted. Agents got rid of it by buying at any price. Wages were indexed and followed: prices could then rise indefinitely. In the course of 1922, Germans kept their currency for an average of just five days, which was extremely short.

July 1922 to October 1923: inflation accelerates to the point of absurdity

These trends became more pronounced from July 1922 to June 1923. France categorically refused to lighten the burden of reparations, and the Allies occupied the Ruhr from January 1923. The German government decreed “passive resistance”, which led to a drop in productivity without a reduction in wages, thus creating an additional source of inflation. The mark devalued and the flight from the currency intensified: prices and wages had to be constantly revised, and money holdings were on the order of a day or two’s income. Businesses could no longer adapt to such monetary instability, and began to lay off workers. Due to a decline in productivity, national income had fallen in 1922, even though full employment had almost been achieved. Unemployment reappeared in October 1922, reaching 25% in November 1923.

From June to October 1923, hyperinflation accelerated to the point of absurdity. Cash on hand represented less than a day’s expenditure, and by September prices were rising by around 20% a day. By mid-1923, foreign currencies were penetrating domestic circulation and all kinds of supplementary currencies were appearing. The situation quickly degenerated. Peasants stockpiled foodstuffs, hungry people rioted and looted. On September 26, 1923, the Chancellor declared in the Reichstag that “the mark is dead”, and a state of siege was declared the following day.

Late 1923-1924: the end of the monetary crisis

Determined decisions were needed to overcome the crisis. Financier Hajmar Schacht, who later became famous as the Weimar Republic’s currency commissioner between late 1923 and 1924, was at the helm. He settled the monetary question in two stages.

Firstly, by creating the Rentenmark on December 1, 1923. This fiduciary currency was distributed in the form of coins and small denominations, with a value of 1 for every 1,000 billion of the old mark. It was secured by mortgages on the agricultural, industrial and wholesale sectors. 4 and put an end to dollar speculation against the mark. The population finally accepted it, putting an end to hyperinflation.

In a second phase, the creation of the Reichsmark on August 30, 1924, complemented that of the Rentenmark, with the two currencies circulating together at a value of 1:1. This new currency was indexed to potential national resources: coal, iron ore and gold. In theory, one Reichsmark is equivalent to 1/2790 kg of fine gold. Both currencies were in circulation until September 1939, with the Rentenmark remaining convertible until 1948.

The lessons of the great inflation

The disorganization of the German economy in 1923 should not obscure the fact that the country’s performance was better than that of countries that had taken restrictive, deflationary monetary measures as early as 1919, as was the case in the USA, the UK and Sweden: most of these countries did not emerge from recession in 1923. In Germany, investment in the real economy remained strong. Wage earners benefited from high production and low unemployment, as minimum wages became widespread. Entrepreneurs generally benefited from the devaluation of their debts and growth. On the other hand, pure rentiers, particularly low-income pensioners, were the losers.

In reality, the policy followed by the fledgling Weimar Republic was probably the only one possible to avoid insurrection. According to the prevailing economic theories of the time, the only way to avoid inflation would have been to restrict aggregate demand through a restrictive credit and tax policy, which would have led to high unemployment and a climate of insurrection. In contrast, the policy followed succeeded in maintaining a high level of activity during the inflationary period, except for the last six months, when economic agents’ mistrust led to a flight from the currency.

Contrary to popular belief, this economic period – from 1919 to 1923 – was characterized by a chronic budget deficit, and the use of “printing money” was not an economic catastrophe. As for hyperinflation, it was primarily due to Germany’s inability to pay war reparations. The result was speculation on the currency, then a loss of confidence in the currency at national level, and price-wage indexation did the rest. Money printing” is more a symptom than a cause.

What are the lessons to be learned?

- Hyperinflation manifests the ruin of money: creditors lose what debtors gain;

- A currency that has experienced hyperinflation must be replaced, because a modern economy cannot function without money;

- Inflation only degenerates into hyperinflation if confidence in the currency disappears. This depends not only on the level of price rises, but also on the overall economic and political context, which has a decisive influence;

- The use of “money printing” was not necessarily the cause of the loss of confidence in money. In the case of the Weimar Republic, the initial cause was clearly the demand for excessive war reparations;

- More generally, we must be wary of simplistic interpretations of monetary phenomena.

Find out more

- Karsten Laursen, Jørgen Pedersen, The German inflation 1918-1923, North-Holland Pub. Co. 1964.

- Ernst Wagemann, Frédéric Coers, D’où vient tout cet argent? : création de monnaie et conduite des finances en temps de guerre et en temps de paix, Plon, 1941.

- Georges Castellan, L’Allemagne de Weimar 1918-1933, Armand Colin, 1968 (digital reprint).

- Michael L. Hughes, Paying for the German Inflation, University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

- Georges Castellan, L’Allemagne de Weimar 1918-1933, Armand Colin, 1968. ↩︎

- This is the value of the mark in 1913, when it was convertible into gold. It was no longer convertible in 1914. ↩︎

- Karsten Laursen, Jørgen Pedersen, The German inflation 1918-1923, North-Holland Pub. Co. 1964. ↩︎

- During this period, all entrepreneurs in these sectors were required to cede 6% of the added value they generated to the state, thereby supporting the Rentenmark. ↩︎