This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The artificialization of land, i.e. the degradation of its ecological functions by urban development, has crucial ecological and social consequences. It directly impacts biodiversity and carbon sinks, increases the vulnerability of territories to floods and droughts, destroys agricultural land and reduces our food sovereignty. Introduced by the 2021 Climate and Resilience Act, the Zero Net Artificialization (ZAN) objective is a central, structuring public policy to combat soil artificialization and its impacts. It affects all areas of land use planning: housing, economic activities, infrastructure, agricultural land, flood prevention, water resource management, etc. It is therefore particularly important to understand their objectives and procedures, which are sometimes complex due to the large number of subjects they cover.

The aim of this fact sheet is to place the emergence of ZAN in context, to present the principles and main ways of implementing this policy, and to discuss some of its practical implications (agriculture, housing, water, climate, etc.). It also focuses on current attempts at deconstruction.

To find out more about the concept of soil artificialization and its impact, please consult our fact sheet on soil artificialization.

ZAN: the culmination of an age-old concern in the age of the Anthropocene

Soil as the planetary limit: towards the ZAN objective

The Zero Net Artificialization objective adopted in 2021 in the French Climate and Resilience Act is the most recent step in a long-standing and ongoing process of soil protection. It reflects our collective awareness of our dependence on these ecosystems, which perform crucial ecological functions (carbon storage, water and nutrient cycles, habitat for biodiversity, etc.) and from which we derive irreplaceable services (provision of food, building materials, fuel, water purification, etc.).

The “zero” in the ZAN target reflects an awareness of the planet’s limits: soils are fragile ecosystems that take thousands or even tens of thousands of years to form. 1and are therefore a non-renewable resource on human timescales.

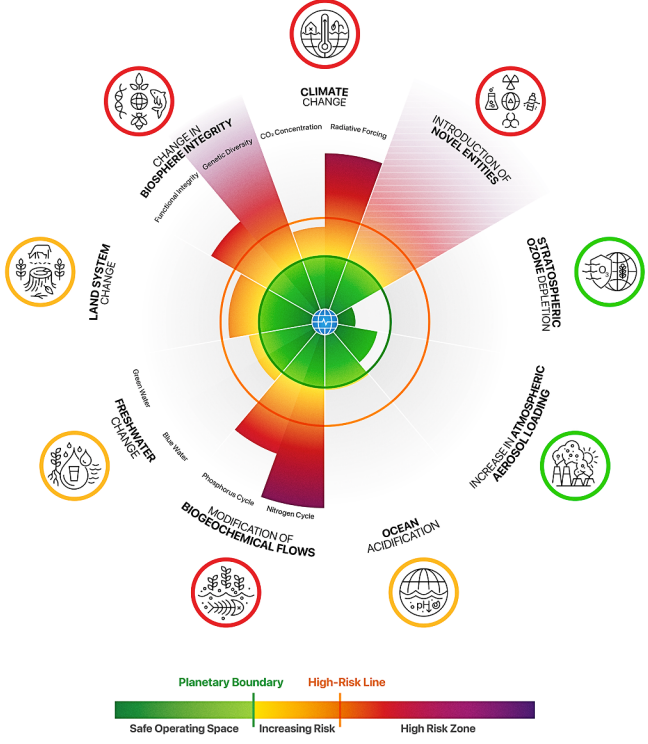

What are the planetary boundaries?

Introduced in 2009 by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen, the concept of planetary boundaries designates the environmental boundaries that must not be crossed or drastic changes to living conditions on the planet will occur. The Planetary Boundaries framework identifies the nine Earth system processes essential for maintaining global stability, resilience and life-support functions. By early 2026, seven out of the nine boundaries identified, have been crossed .

Source: Planetary Health Check 2025, Planetary boundaries science Lab, Potsdam Institute.

From decentralization to ZAN: a long road to soil protection

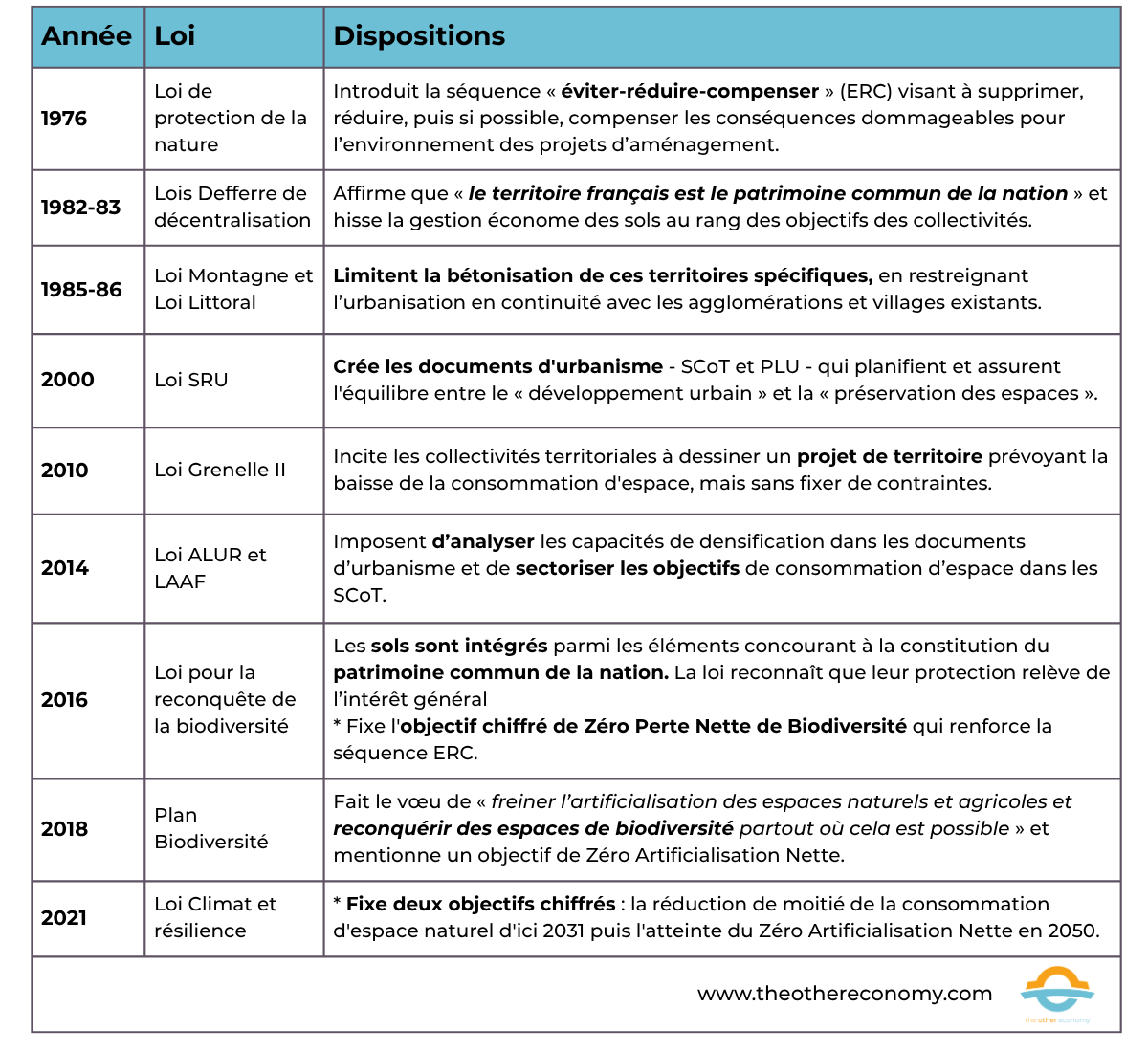

The fight against soil artificialization is a long-standing concern, long predating the introduction of the Zero Net Artificialization (ZAN) objective enshrined in the Climate and Resilience Act of August 22, 2021. ZAN is a further step in a long process aimed at better integrating soil protection into public policy, which the selective chronology below helps to illuminate.

Chronology of measures to reduce the artificialization of land up to the introduction of ZAN by the Climate and Resilience Act

Source Réseau Action Climat (modified)

As early as 1976, the French Nature Protection Act introduced the “avoid, reduce, compensate” principle. “avoid, reduce and compensate (ERC) principle for land development projects, foreshadowing the logic of Zero Net Artificialization compensation 45 years later.

From 1982 onwards, the decentralization laws transferred responsibility for urban planning to local authorities. 2 and the creation of “land-use plans”. In 2000, the French Solidarity and Urban Renewal Act (SRU) created urban planning documents (SCoT and PLU). 3), which are required to determine “the conditions for ensuring the” “economical and balanced use” of “of natural, urban, suburban and rural spaces”. Soil is not yet directly concerned, but the objective of limiting urban sprawl is clearly present.

In 2010, this legislative movement in favor of soil preservation was extended by the Grenelle II law. PLUs must now include “objectives for moderating the consumption of space and combating urban sprawl”. 4. Four years later, the ALUR law specified that these objectives must be quantified, and that urban planning documents must analyze “the capacity for densification and mutation of all built-up areas”. 5.

In 2016, the law for the reconquest of biodiversity affirmed that soils contribute to the constitution of the “nation’s common heritage”, without however going so far as to recognize that they are an integral part of it.

It introduces into the Environment Code ( art. L110-1 ) a list of numerous elements as part of the nation’s common heritage, but not soil: “spaces, resources and natural environments on land and at sea, the sounds and smells that characterize them, sites, day and night landscapes, air quality, water quality, living beings and biodiversity”.

Although they are both essential habitats and non-renewable resources, soils are only considered as elements that “contribute to the constitution” of our common heritage, as production factors and not as inherent wealth. Nevertheless, soil protection is recognized as being in the public interest.

The law also reinforces the “avoid, reduce and compensate” sequence by introducing an objective of no net loss of biodiversity and an obligation to achieve results in terms of ecological compensation. 6.

In 2018, the Government’s Biodiversity Plan mentions a goal of Zero Net Artificialization and envisages a consultation to set the trajectory for achieving it.

In consultation with stakeholders, we will define the timeframe for achieving the “zero net artificial development” objective, and the trajectory for achieving it progressively. When renewing their urban planning documents, local authorities will have to set themselves a target for controlling or reducing land artificialisation that is compatible with the trajectory defined at national level, while taking account of specific local circumstances.

This long process of progressive soil protection in French law culminates in the inclusion of the ZAN objective in the Climate and Resilience Act of August 22, 2021, which follows on from the work of the Citizens’ Climate Convention 7.

Zero Net Artificialization (ZAN) target: principles and implementation

The ZAN objective was introduced in the 2021 Climate and Resilience Act. The implementation procedures were then specified in April 2022 in the “SRADDET decree”, for the territorial declination and in the “nomenclature decree” aimed at clarifying which types of surfaces would be considered as artificialized or not.

This initial ZAN architecture gave rise to lively debate and controversy, particularly among the Association des Maires de France and the French Senate, and was substantially modified and weakened by the ZAN law of July 2023 and subsequent decrees.

We present below the current state of the law resulting from these multiple modifications, which is likely to be seriously challenged once again by the so-called “simplification of economic life” law and the TRACE law in 2025.

Climate and resilience law: definition of land artificialisation and adoption of quantified targets to tackle it

The notion of soil artificialisation was first defined in law in 2021, thanks to the Climate and Resilience Act. However, this is a much older concern: previously, the term “artificialisation” referred to the process of urbanization, whereby natural, agricultural or forested areas (ENAF) are developed for residential, economic, industrial or other uses. So, before the Climate and Resilience Act, artificial land was defined as land that was no longer used for agricultural, natural or forestry purposes.

Historically (since the post-World War II period), the monitoring of soil artificialisation has been conceived as the monitoring of changes in land use, i.e. first as the loss of agricultural land, then more broadly as the loss of natural, agricultural or forest areas (ENAF) to urbanized areas.

The Climate and Resilience Act (2021) introduced two complementary objectives in the fight against land artificialisation:

- halve the consumption of FFPE over the 2021-2031 period, compared with the previous decade (2011-2021);

- achieve zero net artificialisation (ZAN) by 2050, in line with the goal of carbon neutrality.

The first objective, which involves halving the expansion of urbanized areas, represents a first step towards achieving ZAN by 2050. However, the law does not specify an intermediate target for the following decade (2031-2041).

The second objective, to achieve Zero Net Artificialization by 2050, is based on the definition of artificialization newly introduced into the town planning code by law, and distinct from the consumption of ENAF.

“Artificialization is defined as the lasting alteration of all or part of a soil’s ecological functions, in particular its biological, hydric and climatic functions, as well as its agronomic potential through its occupation or use.”

Soil renaturation (or desartificialisation) is defined as the reverse movement, aimed at restoring or improving the ecological functions of a soil.

“Soil renaturation, or desartificialisation, consists of actions or operations to restore or improve soil functionality, having the effect of transforming artificial soil into non-artificial soil.”

Lastly, “net” artificialisation is defined as “the balance between artificialisation and renaturation of land within a given perimeter and over a given period”.

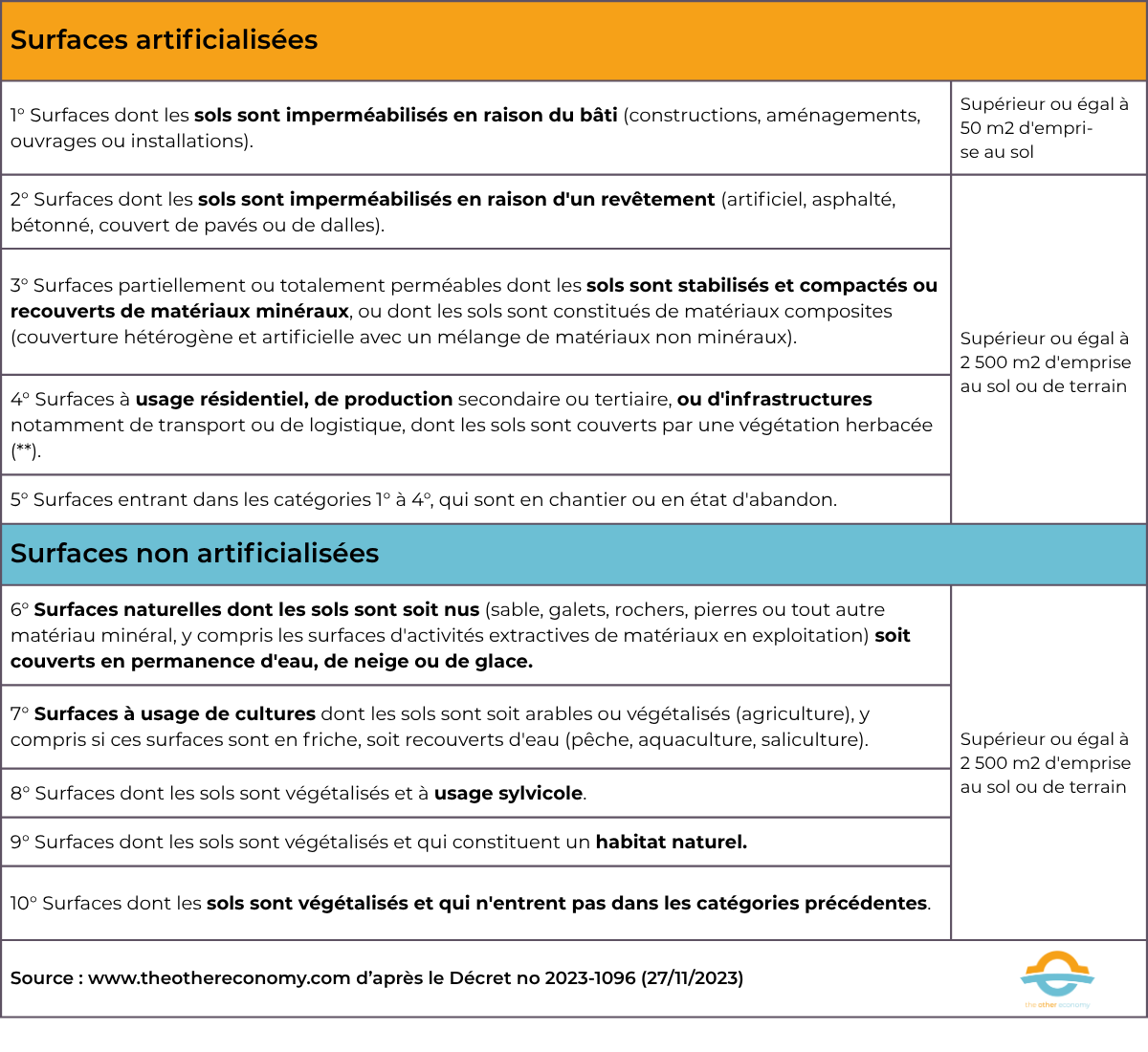

A binary application of the definition of soil artificialisation

While the definition of artificialisation cited above refers to the alteration of “all or part of the ecological functions of a soil”, the law does not allow soils to be considered as more or less artificialised (according to a gradation), but provides for a binary division between artificialised and non-artificialized surfaces in urban planning documents. As a result,

Artificial” means a surface whose soils are either waterproofed due to construction or paving, or stabilized and compacted, or made of composite materials;

A “non-artificialized” area is one that is either natural, bare or covered with water, or vegetated, constituting a natural habitat or used for crops.

This distinction does not, of course, cover all possible scenarios: a “nomenclature” for soil artificialisation was published in a decree in April 2022. This was contested and appealed, before being reworked and published in a modified version in November 2023, following the promulgation of the ZAN law in July 2023 (see section 2.3 on the nomenclature of soil artificialisation).

Territorializing ZAN: a difficult exercise

The national objective of halving the consumption of ENAF over the period 2021-2031 compared with the previous decade is to 8 be territorialized, i.e. integrated into the various levels of territorial planning.

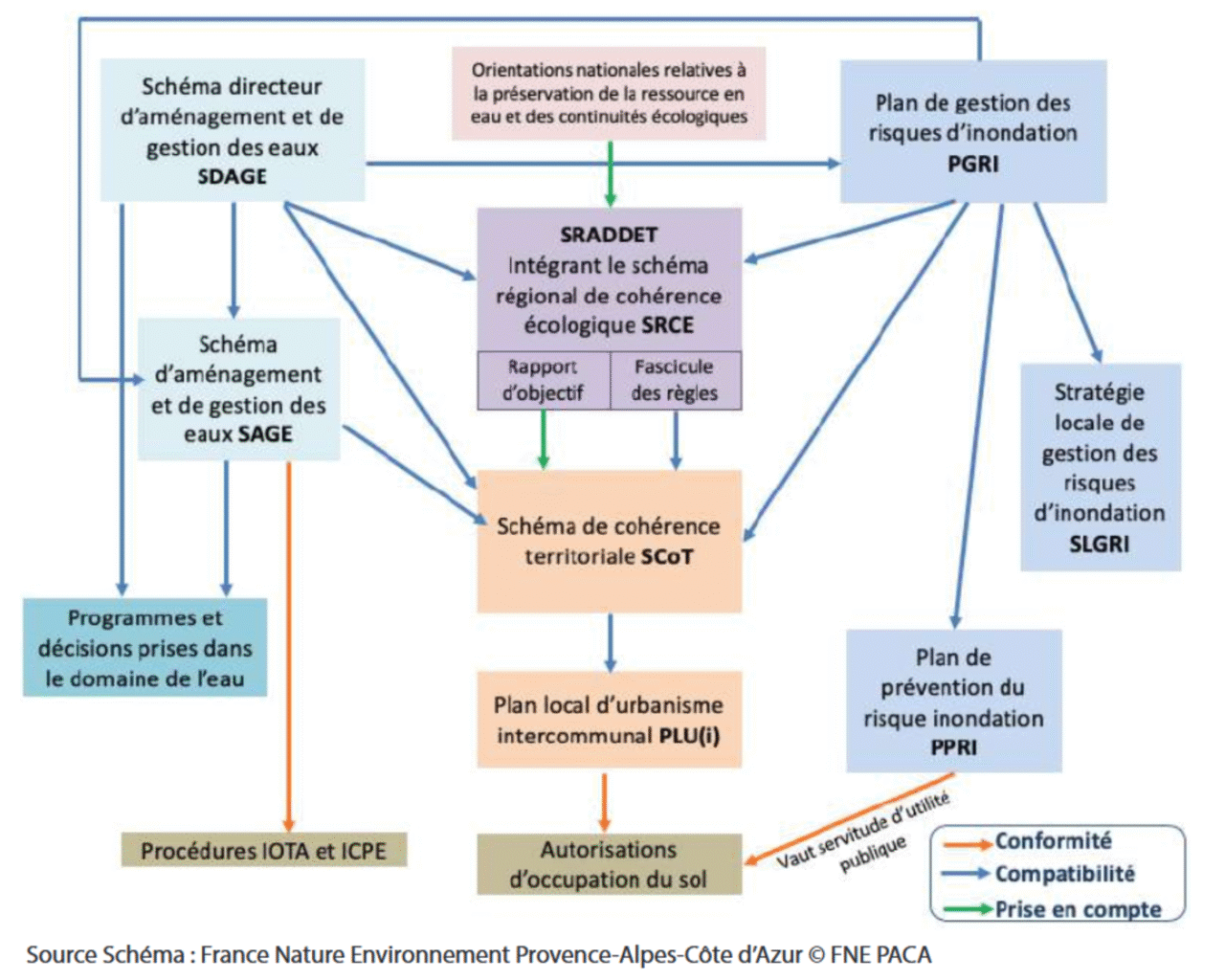

Understanding territorial planning and urban development documents

Drawn up by local authorities, planning and urban development documents are intended to set the strategic direction of the territory in various fields (infrastructure, mobility, economic development, etc.) and to lay down rules for development, land use and occupation, construction, the protection of spaces, and so on. The various planning and urban development documents – at regional, catchment, intercommunal or even local level – are linked by varying degrees of enforceability. Depending on the case, certain prescriptions of the higher level must be strictly respected or simply taken into account at the lower level (three levels of opposability: conformity, compatibility, taking into account). 9.

At regional level – SRADDET

In most French regions 10the main regional planning guidelines are set out in the Schémas régionaux d’aménagement, de développement durable et d’égalité des territoires (SRADDET). These contain a report of objectives, a set of rules and appendices. The rules set out in the fascicule are enforceable against the SCoTs by virtue of their compatibility, whereas the objectives set out in the report must only be “taken into account” by the SCoTs (the rules of the SRADDET are therefore more binding than its objectives).

At the catchment area level – SCoTs

The aim of the Schémas de cohérence territoriale (SCoT) is to establish strategic planning on the scale of a catchmentarea, thus providing a framework for a series of public policies: urban planning, housing, mobility, commercial development, environment, energy and climate, biodiversity, etc.

The SCoT plays an “integrating” role: it brings together the prescriptions of higher-level planning documents (the SRADDET), as well as other documents dealing with specific areas (such as the SDAGE and SAGE on water, or the SRCE on ecological corridors). The SCot thus serves as the sole legal reference for PLU(i) and cartes communales.

The SCoT is made up of a Projet d’Aménagement Stratégique (PAS), which aims to project the territory over a 20-year horizon, and a Document d’Orientation et d’Objectifs (DOO), which defines localized and sometimes quantified orientations. Appendices are also attached to the SCoT, including its environmental assessment.

In the absence of a SCoT, communes are subject to the “principle of limited urbanization”, which prevents new land from being opened up for urbanization in PLU(i) plans, although exemptions are possible.

At (inter)municipal level – PLU(i) plans

The local (or inter-communal) urban development plan must be compatible with the PAS and DOO of the SCoT. 11. The PLU(i) is the urban planning document that operationalizes land-use planning, and articulates a diversity of issues (housing, mobility, environment, activities, etc.) on the communal or inter-communal territory.

Another local tool, the carte communale is a simple urban planning document designed for small communes, enabling them to delimit buildable and non-buildable sectors within their territory. The carte communale must also be compatible with the SCoT.

The ZAN objective cascaded from national to local level

According to the Climate and Resilience Act :

- regions covered by a SRADDET (i.e. metropolitan regions excluding Île-de-France and Corsica), must take up the 50% reduction target by 2031 and localize it;

- The other regions (Île-de-France and Corsica) and overseas territories must themselves determine the ENAF consumption reduction target to be included in their planning documents. 12 – this is not specified in the law 13. In its SDRIF-E, the Île-de-France region has set a reduction target of 20% by 2031, compared with 2011-2021. 14.

By November 2024, SRADDETs and other regional planning documents were to include targets for reducing the consumption of NFE by 2031 (this work is still in progress in some regions).

What’s the status of ZAN’s integration into regional plans?

“To date, half of the continental regions (6 out of 12) now have a planning scheme in force setting a trajectory (Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, Bretagne, Hauts-de-France, Normandie, Nouvelle-Aquitaine, Île-de-France) and three regions are continuing their work, which should be completed by the first half of 2025 (Grand Est, Occitanie, Sud).”

“In some overseas collectivities (notably French Guiana and Reunion Island) and Corsica, which have opted for a more cumbersome revision procedure, adoption should take place in 2026.”

“On the other hand, only three regions have no or no longer any modification schedule (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, Centre-Val de Loire, Pays de la Loire)”.

Source Rapport d’information de l’Assemblée nationale sur l’articulation des politiques publiques ayant un impact sur l’artificialisation des sols, April 2025.

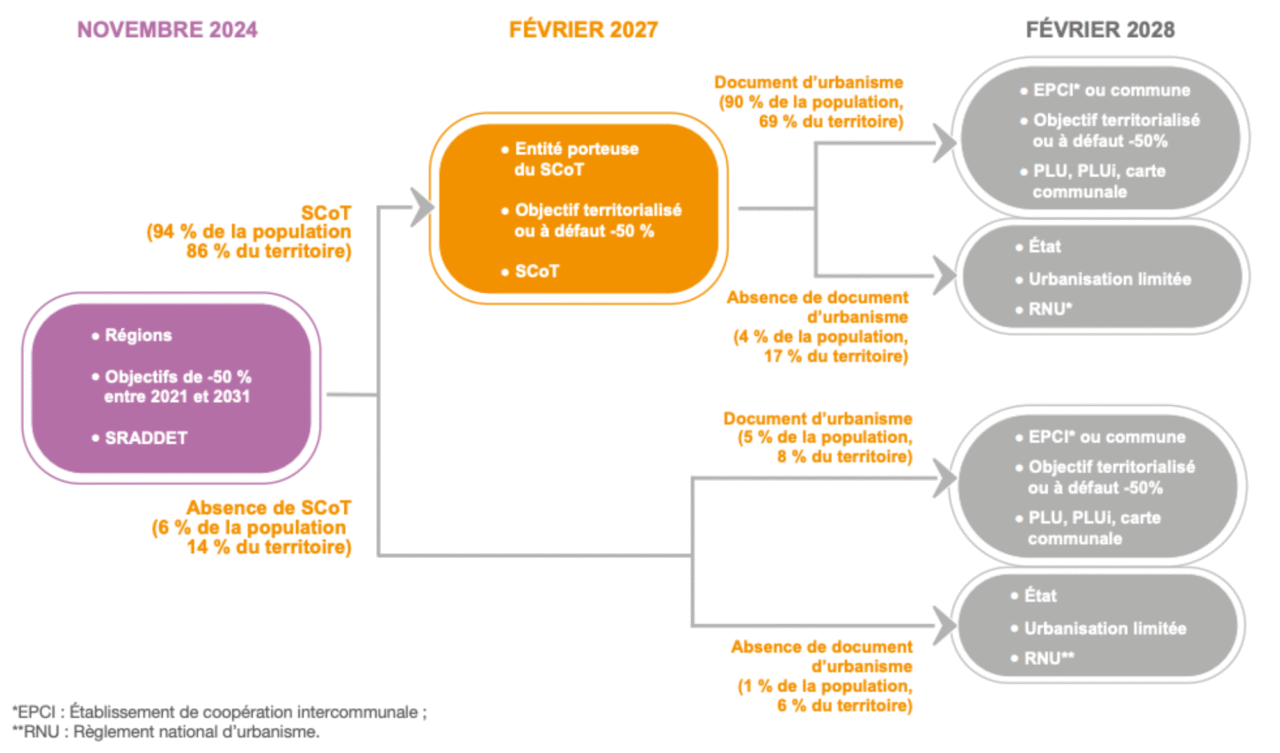

These objectives will then have to be integrated into the SCoTs by February 2027, and finally into the PLU(i) by February 2028. 15.

For areas not covered by SCoTs, the objectives can be incorporated immediately into PLU(i) or cartes communales, or taken over by the State in the absence of urban planning documents. The diagram below, produced by France Stratégie, summarizes the possible situations.

Cascading integration of the objectives of the Climate and Resilience Act

Reading: SCoTs will have to incorporate the territorialized targets (or, failing that, a target for halving space consumption) set out in regional SRADDETs by February 2027. Local authorities with urban planning documents (PLU, PLUi or carte communale) must then incorporate these objectives into their urban planning documents before February 2028.

The arrows indicate a relationship of opposability. For example, the SRADDET is enforceable against the SCoT.

Source Objectif ZAN : quelles stratégies régionales, France Stratégie, Note d’analyse n°129, Nov. 2023 (p. 5)

This territorialization of the ENAF consumption reduction target has been designed to distribute efforts to reduce land use in a differentiated way across sub-regional territories (SCoTs and EPCIs).

Thus, the aim of the law is not to uniformly impose a 50% reduction in the consumption of electricity and gas from the national level down to all PLUs: the distribution of sobriety efforts must be carried out at regional level, taking into account the past and present dynamics of the territories.

The SRADDET decree of April 2022 thus indicated that targets for reducing consumption of ENAF were to be “territorially broken down by considering:”

- “1° The challenges of preserving, enhancing, restoring and restoring natural, agricultural and forest areas, as well as ecological continuity;”

- “2° The land potential that can be mobilized in areas that have already been developed, in particular by optimizing density, urban renewal and brownfield redevelopment;”

- “3° Regional balance, taking into account urban centres, infrastructure networks and the challenges of opening up rural areas;”

- “4° Foreseeable demographic and economic trends, particularly in the light of available data and the needs identified in local areas.

The decree also provides for the possibility of accounting for artificialisation induced by projects of regional scope at regional level, rather than on the envelope of communities where the projects are located – so as to mutualize the land footprint of projects that benefit the whole region.

Weakening of the legal enforceability of targets to reduce artificial growth

The SRADDET decree of April 2022 provided for the integration of ENAF consumption reduction targets into the SRADDET to be achieved by means of “territorialized rules ⦗permettant⦘ to ensure the declination of targets between different parts of the regional territory” 16.

The use of the term “rule” is important: lower-standard urban planning documents (SCOTs) must be “compatible” with the rules set out in SRADDETs. The “objectives” of the SRADDET, on the other hand, must only be “taken into account”, which is a lower level of legal constraint and leaves more room for discretion to the elected representatives concerned.

In June 2022, the AMF filed an appeal 17 to oppose the inclusion of targets for reducing land artificialisation in the rules of SRADDETs, arguing that this provision was contradictory to the Climate and Resilience Act. Despite the rejection of this appeal by the Conseil d’Etat in October 2023 18the government chose to go along with the AMF’s request.

The “territorialization decree” of November 2023 has thus reduced the level of constraint of ZAN objectives: the integration of quantified and territorialized objectives among the rules of the SRADDET 19 rules is now a possibility left to the discretion of the Regions (and no longer an obligation).

Going even further, the TRACE bill of 2025 seeks to do away with national and regional targets altogether, leaving each territory free to set its own trajectory for reducing artificialization. In the absence of national targets and regional rules enabling efforts to be shared between different territories and over time, it is hard to see how Net Zero Artificialization can be achieved by 2050.

Consideration of “projects of national or European scope” (PENE)

The 2023 ZAN law extended the logic of regional-scale projects 20 to projects of “national or European scope” (PENE), after local authorities reported that major infrastructure projects had consumed a very large share of their land envelope (e.g.: Seine-Nord Europe Canal in the Hauts-de-France region).

The aim is to mutualize the land footprint of major projects, so that the ENAF consumption they entail is not counted entirely against the envelope of the region where the project is located. The logic is that if the State considers that a project has a national benefit, its land consumption cannot be based on a single region alone.

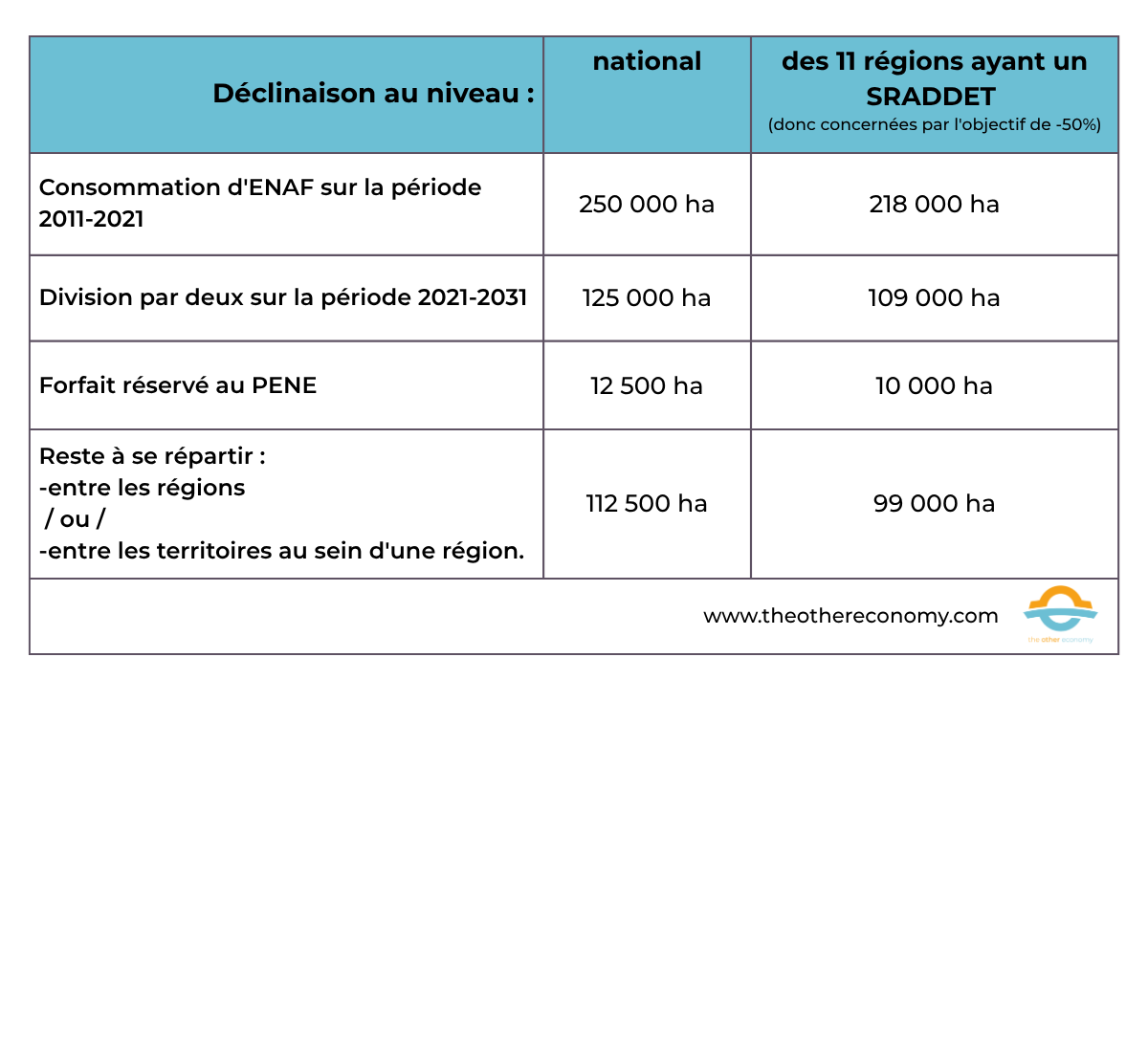

A national “PENE” package has therefore been set at 12,500 ha, i.e. 10% of the national land envelope for 2021-2031. The remaining 90% of the envelope is then divided between the regions, as part of the territorialization of objectives. For the 11 regions covered by a SRADDET, 10,000 ha will be pooled for the PENEs (the remaining 2,500 ha concern the other regions). By collectively reserving the 10,000 ha for PENE, each region covered by a SRADDET must reduce its consumption of ENAF by 54.5% (rather than 50%) between 2021 and 2031, compared with the previous decade. 21.

Understand the breakdown of quantified targets for reducing the consumption of FSCA

Reading: At national level, halving the consumption of ENAF over the 2021-2031 period compared to 2011-2021 is equivalent to allowing the consumption of around 125,000 ha. Of this envelope, the law provides for 12,500 ha (10%) to be set aside for PENE, before the remainder (around 112,500 ha) is distributed between the regions.

Focus on Projects of National or European Scope (PENE)

The law specifies the types of projects that can be considered PENEs. 22namely :

works or operations declared to be in the public interest by decree of the Conseil d’Etat;

construction of high-speed rail lines;

industrial projects of major interest to national sovereignty or the ecological transition, as well as those that play a direct part in the value chains of activities in the sectors of technologies conducive to sustainable development;

development projects carried out by a major state-owned sea or river port;

operations relating to national defence or security;

prison construction or renovation projects;

operations carried out within the perimeter of an Operation of National Interest (OIN) 23) ;

building an electronuclear reactor;

construction or development of substations with a voltage of 200 kV or more.

The precise list of projects considered to be of national or European scope, and which will cause an effective consumption of ENAF over the period 2021-2031 was then published in appendix 1 of the order of May 31, 2024 24.

Consult Cerema’s interactive PENE map.

The creation of the “communal guarantee

Introduced by the ZAN law of 2023, the communal guarantee aims to ensure that each commune will have a minimum envelope of one hectare of ENAF, which it will be able to consume over the period 2021-2031. Initially proposed by the senators in response to the fears of certain rural communes that their voice would not be heard in regional negotiations, this idea of a “rural guarantee” was eventually extended to all communes (to become the “communal” guarantee), regardless of their size, densification potential or territorial dynamics (demographic, economic and social, etc.).

This system confirms the idea that there is a form of unconditional right to develop land, also presented as a “right to project”, without specifying the nature of these projects or the reasons for their development. It also implies that it would necessarily be impossible to carry out new projects without artificialising new natural, agricultural or forest areas.

This communal guarantee applies to all communes covered by an urban planning document prescribed, adopted or approved before August 22, 2026. The aim is to encourage communes that have not yet done so to draw up an urban planning document in order to benefit from this minimum envelope of ENAF consumption.

In the process of territorializing ZAN, however, this communal guarantee complicates the equation aimed at distributing artificialisation capacity. In 2025, of the 35,014 French communes, 26,840 are covered by a town planning document (published or not) 25 and will therefore be able to consume at least 1 ha of ENAF over the 2021-2031 period, although this does not necessarily correspond to the needs of all the territories concerned, and land tensions may exist elsewhere.

This is also the conclusion reached by the members of parliament who produced the information report on the coordination of public policies that have an impact on soil artificialisation.

The rapporteurs have noted that the practical application of this “communal guarantee”, which is positively perceived by rural elected representatives, raises a number of application difficulties, insofar as it is not always easy to integrate this constraint, particularly for territories with many eligible communes.

For example, the SRADDET of the Hauts-de-France region includes 3,788 municipalities benefiting from the guarantee for 5,934 hectares to be distributed, from which 1,483 hectares must be subtracted for projects of regional scope, leaving 663 hectares to truly territorialize the effort to reduce the consumption of ENAF.

(…) it seems that the pooling of these hectares on an inter-communal scale, which many players are calling for, is in fact not being implemented, or only very rarely. This is why the rapporteurs are proposing to reverse the logic by allowing only rural communes to request, by deliberation of their municipal council, to benefit from a minimum area of ENAF consumption.

While the principle of a guarantee for rural areas is a useful one, it is regrettable that it is not rooted in the characteristics of these areas (surface area already built-up, potential for urban renewal, demographic and socio-economic dynamics, etc.).

Other changes introduced by the ZAN Act in connection with territorialization

The parliamentary debates having finally discarded proposals that sought to exempt various economic activities from sober land use. 26 or to create derogations in the accounting of artificialised hectares, the ZAN law of July 2023 ratified other modifications to the initial system.

These include the creation of regional ZAN governance conferences, the possibility, from 2021 onwards, of counting renaturalized areas against the total built-up area, the inclusion of areas subject to coastline erosion, and the creation of specific tools such as the ZAN “sursis à statuer” and the extension of urban pre-emption rights.

- The “sursis à statuer ZAN” allows mayors to wait for urban planning documents to be revised before taking a decision on certain projects, for example in cases where the application of ZAN would mean reclassifying a constructible zone as a natural area.

- Extension of urban pre-emption rights, to facilitate the use of this lever in strategic areas for the purposes of urban renewal, optimizing density, rehabilitating wasteland or preserving/restoring nature in the city. 27.

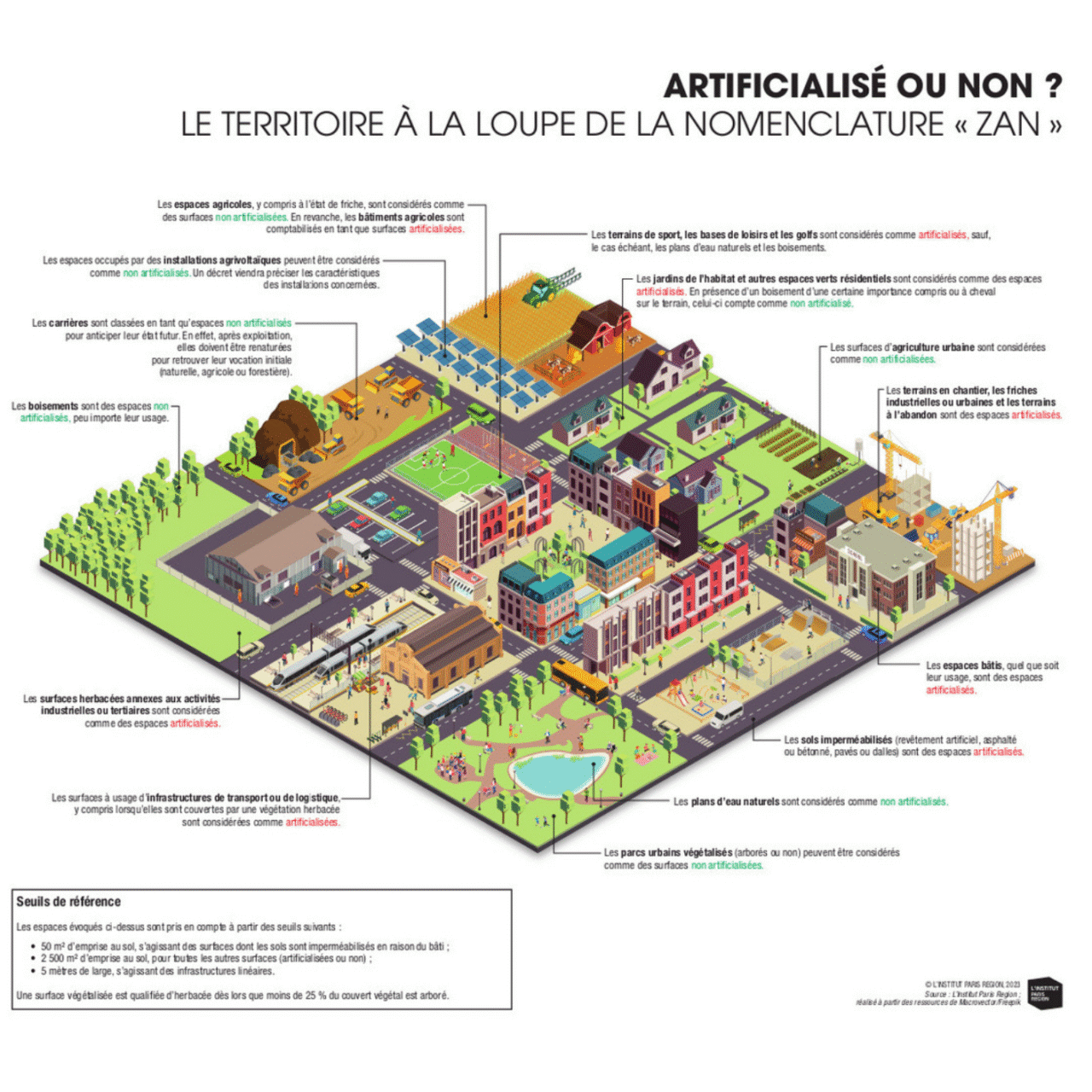

Understanding soil artificialisation nomenclature

From 2031 onwards, the monitoring of targets for reducing land artificialisation will no longer be based solely on the indicator of ENAF consumption, but also on land artificialisation itself, i.e. as defined in the 2021 Climate and Resilience Act and assessed on the basis of the nomenclature published in the April 2022 decree (and modified by the November 2023 decree).

This nomenclature for soil artificialization is based on a binary distinction between artificialized and non-artificialized soils. It should be noted that proposals have been put forward in favor of a system based on a gradient of artificialization, rather than a binary distinction, in order to recognize that the ecological functions of a soil can be more or less altered, in line with the definition of artificialization set out in the law. 28.

The land artificialisation nomenclature therefore distinguishes 10 types of land occupation and use, classified as either artificial or non-artificial, as shown below. It is intended to be applied via an automatic satellite image processing tool developed by IGN and entitled OCS GE: Occupation du sol à grande échelle (large-scale land use). 29.

It should be noted that, surprisingly, “surfaces used for material extraction activities” such as quarries and mines are classified as undeveloped surfaces, on the grounds that their impact on the soil is limited to the period of exploitation, after which the site should be renaturalized. 30

Nor are these areas included in the consumption of ENAF. This raises questions, both in terms of the duration of the impacts (decades or even centuries) and in terms of the reality of post-mining renaturation. 31.

Focus on the modification of the nomenclature decree in 2023

The first version of the nomenclature, which will be used to track the evolution of land artificialisation from 2031 onwards, was published in April 2022, and modified the following year.

This change follows on from debates concerning the classification of grassland in residential, industrial, tertiary and infrastructure (transport or logistics) areas as artificial. This choice was made in view of the fact that the ecological functions of these soils, although covered by grass, are at least partially impaired by their use, which leads to management methods and disruptions to ecological continuity that are incompatible with full ecological functionality. In addition, considering grassy areas within urbanized areas (such as private gardens) as systematically non-artificialized would have been a considerable brake on the densification effort needed to avoid the extension of urbanized areas at the expense of natural, agricultural and forest areas.

The compromise adopted in the new decree is as follows: grassed areas in industrial, tertiary and infrastructure areas, and private gardens, remain classified as artificial soil; public green spaces over 2,500 m² are classified as non-artificial soil.

The aim is to reconcile the densification of residential areas with the promotion of green spaces in urban areas, large enough to guarantee the multifunctionality of the land. However, this threshold may raise questions about the creation of smaller green spaces, which may be given less priority, even though they are also needed to increase ecological connectivity. 32 within urban spaces, combat heat islands and improve the living environment for all residents.

To make it easier to understand this nomenclature of land artificialisation, the Institut Paris Région has created the infographic below, illustrating the various cases mentioned in the decree.

Illustration of the different cases provided for in the soil artificialisation nomenclature

Source Institut Paris Région

Photovoltaic power plants

In order not to hinder the development of renewable energies, the French Climate and Resilience Act provides for a conditional exception in the calculation of ENAF consumption for ground-mounted photovoltaic installations. 33. In order not to be counted as urbanized space, a photovoltaic plant installed on natural or agricultural land must meet three cumulative conditions:

Installation reversibility ;

Maintain vegetation cover appropriate to the nature of the soil and the permeability of access roads;

In agricultural areas, the maintenance of significant agricultural or pastoral activity.

The technical aspects of these three conditions are specified in the Order of December 29, 2023.

In 2025, new challenges for ZAN

The “simplification of economic life” bill also seeks to empty ZAN of its content

In the spring of 2025, examination of the “simplification of economic life” bill 34 provided another opportunity to revisit ZAN’s objectives. At the date of publication of this fact sheet, the text had been voted in the Senate, then adopted by the National Assembly (on June 17, 2025), but must now be debated by the Joint Committee, in order to bring the Senate and Assembly versions into line with each other.

The changes introduced in the text voted by the National Assembly largely empty ZAN of its content. The aim is not to improve the implementation of this public policy, but to render it ineffective. In particular, the measures adopted would make it possible to:

- to exclude all industrial projects declared to be of “major interest” by order of the Minister for Industry, as well as all “developments, equipment and housing directly linked to the project”, from the ENAF consumption calculation;

- remove other industrial projects from the local count of ENAF consumption, for a period of 5 years, in order to allocate them to a national envelope of 10,000 ha.

- to include in PLU(i) and cartes communales, without justification, the possibility of urbanizing 30% more land than the maximum local target for ENAF consumption resulting from territorialization (for the period 2024-2034). The text also stipulates that this excess may exceed 30% with the agreement of the departmental prefect.

In short, it’s not a question of finding useful adjustments but of going backwards, to prolong the dynamics of urban sprawl and land artificialisation without regard for the ecological and social consequences.

The proposed “TRACE” law: review the definition of artificialisation, remove the intermediate objective

On November 7, 2024, a new bill was tabled in the Senate to revisit the ZAN legislative framework for a second time. Preferring to speak of Trajectoire de Réduction de l’Artificialisation Concertée avec les Élus locaux (TRACE) rather than Zéro Artificialisation Nette (ZAN), the signatory senators propose a series of measures which largely empty ZAN of its content. The text voted in committee by the Senate includes the following provisions.

- Revisit the definition of soil artificialisation, removing all reference to the ecological functions of soils, and retaining only the notion of consumption of ENAF.

- Eliminate the intermediate target of halving consumption of NFE by 2031 at national level and in each region. The text voted in committee proposes to abolish the ten-year reduction targets, replacing them with intermediate targets set by each local authority.

- Remove projects of national or European scope from the calculation of ENAF consumption for a period of 15 years.

- Create a series of derogations for activities whose land footprint would not be taken into account in ENAF consumption (industrial sites and social housing in particular).

This measure would distort the monitoring of ENAF consumption and complicate the assessment of whether targets have actually been met. It would seem more appropriate to adopt a logic of prioritization, by reserving land envelopes for activities considered to have priority, within the framework of the planned trajectory for reducing artificialization – rather than acting as if these activities had no land impact.

In addition, the proposed law seeks to reconsider the application of the communal guarantee, which is foreseeably causing difficulties (see 2.2.4), in order to enable the pooling of the relevant land envelopes at SCoT and regional level (and not just at EPCI level).

On March 6, 2025, the government launched an accelerated procedure, enabling the text voted in the Senate to be submitted to the National Assembly for a single reading, before a possible joint committee. 35.

Find out more about the laws and main decrees governing the zero net artificial development policy.

Find out more

Net Zero Artificialization Policy initial version

- Climate and Resilience Act (LOI n° 2021-1104 of August 22, 2021 on combating climate disruption and strengthening resilience to its effects)

- SRADDET” decree (Decree no. 2022-762 of April 29, 2022 on the objectives and general rules for sparing land use and combating land artificialisation of the regional plan for land use, sustainable development and territorial equality)

- Nomenclature” decree, version 1 (Decree no. 2022-763 of April 29, 2022 on the land artificialisation nomenclature for setting and monitoring targets in planning and urban development documents).

Modification of ZAN in 2023

- ZAN Law (LAW no. 2023-630 of July 20, 2023 aimed at facilitating the implementation of objectives to combat the artificialization of land and strengthen support for local elected officials)

- Nomenclature” decree, version 2 (Decree no. 2023-1096 of November 27, 2023 on the assessment and monitoring of soil artificialization)

- Territorialization” decree Decree no. 2023-1097 of November 27, 2023 on the implementation of territorialization of the objectives of economical management of space and the fight against soil artificialization.

- Decree no. 2023-1098 of November 27, 2023 on the composition and operating procedures of the regional conciliation commission on soil artificialization.

- Order of December 29, 2023 defining the technical characteristics of photovoltaic energy production facilities exempted from being taken into account in calculating the consumption of natural, agricultural and forestry space.

Beyond the technical debates, ZAN touches on many issues of ecological and social transition

Food sovereignty and the renewal of agricultural generations

Land artificialisation is not just a question of urban planning. The driving forces behind the dynamics of land artificialisation are rooted in many areas, including the agricultural economy, with its issues of remuneration, pensions, access to land and generational renewal.

Land artificialisation continues at the expense of agricultural land

Land artificialisation is a threat to food sovereignty. According to data from the French Ministry of Agriculture (Teruti-Lucas survey), the artificialized surface area – in the sense of consumption of ENAF 8 – increased by 80% between 1982 and 2022 in mainland France, from 2.9 Mha to 5.215 Mha (or 9.5% of the national territory). 37.

Two thirds of this growth in built-up areas has been at the expense of agricultural land. 38. This trend is all the more worrying given that the rate of land artificialisation is rising much faster than that of the French population, which has only increased by 19% over the same period. 39. Worse still, a study by Cerema has shown that in more than a quarter of French communes, artificialisation increased between 2011 and 2016 even as the number of households declined 40.

While the farming population continues to decline

While the French population continues to grow, agricultural demographics continue to erode. A long decline, the chronology of which helps to illustrate the scale of the transformation undergone by French agriculture. Indeed, while France has lost 320,000 full-time agricultural jobs over the past 20 years, looking back a few decades reveals some edifying orders of magnitude. Although the decline in the farming population had already begun in the mid-19th century, it accelerated after the Second World War. Between 1946 and 1968, France’s active farming population was reduced by 3% per year, a drop of 54% in two decades. 41. Agricultural modernization (mechanization, land consolidation 42the reduction in the number of farmers continued over the following decades: while France still had 1.6 million farmers in 1982 (7.1% of total employment), there were just 400,000 farmers in 2019 (1.5% of the total), a fourfold reduction. 43.

More and more farmland destroyed, fewer and fewer farmers. These two trends must be reversed if we are to make a success of the agro-ecological transition and provide access for all to healthy, sober, local food, all against a backdrop of demographic growth – INSEE forecasts a population of 76 million in France by 2070. 44.

In a critical context of generational renewal in agriculture

Generational renewal in agriculture is a major challenge: by 2035, 60% of farm managers will be retiring. 45. By 2030, half of all active farmers in 2020 will have left the sector. 46. Today, one farmer in three who retires is not replaced. As a result, the basic dynamic observed for over half a century is continuing: a reduction in the number of farms and an increase in the average surface area of those that remain. 47while a proportion of farmland is used for urban sprawl.

In this sense, agricultural demography and the dynamics of land artificialisation are closely linked: in a book entitled La ville stationnaire: comment mettre fin à l’étalement urbain? (Actes Sud, 2022), Philippe Bihouix, Clémence de Selva and Sophie Jeantet demonstrate that the financial flow generated by land artificialisation (the sale of land for construction projects) constitutes “the other agricultural income”, of a similar order of magnitude to that derived from agricultural production.

Over the next few years, therefore, it’s crucial that massive retirements don’t result in more farmland being built up.

Climate change: mitigation and adaptation

Soil, a little-known carbon sink

Soils are a crucial carbon sink: the carbon stock contained in the first 30 centimetres of soil is three times higher than that contained in forest wood. 48. Artificialization causes rapid destocking of soil carbon, as a result of the development work carried out (earthworks, waterproofing, etc.).

Against a backdrop of unprecedented decline in terrestrial carbon sinks 49particularly forest ecosystems in France 50the crucial role of soils in the climate system, and the importance of protecting them, must be given greater prominence in public debate.

The crucial question of water

As we explain in the ” Understanding soil artificialization and its impacts ” fact sheet, soil artificialization has a major impact on the water cycle: it reduces soil infiltration capacity, accelerates runoff and increases the risk of flooding. This has consequences both in terms of increased risks and the availability and quality of water resources.

In addition to these impacts, we also need to consider the link between water management and the implementation of the ZAN objective. Indeed, under the impact of climate change, many regions will experience growing pressure on water resources due to increasingly frequent droughts. 51. Continued urbanization in areas where water resources are already under pressure therefore seems particularly questionable.

The situation in the Pays de Fayence (Var) in winter 2023 is instructive in this respect. In the absence of sufficient water, the Pays de Fayence community of communes decided on January 31, 2023 to stop granting building permits for new homes, for a period of 5 years. 52. On March 10, the Prefect of the Var sent a letter 53 to the President of the Communauté de Communes and the mayors of the Pays de Fayence communes, pointing out that “this trend [of drought] seems likely to be repeated in the future and is part of the process of climate change”, asserting that it was “necessary to organize a pause in urbanization so as not to increase pressure on water resources” and inviting elected representatives to “refuse applications for planning permission for projects that generate water consumption”. On February 23, 2024, the Toulon Administrative Court upheld the Pays de Fayence local authority’s decision. 54. The judges noted that there was a short-term shortage of water resources in the area, and recognized that the new project refused by the commune did indeed present a risk to public health.

This raises the question of how to take into account the availability of water in the context of the demographic and economic projections that underpin urban planning. As part of the territorialization of ZAN, the potential for artificialisation is distributed between territories, taking into account their demographic and economic dynamics (see section 2.2). It is also crucial to ensure that projected dynamics are consistent with current and future water availability. From this point of view, more work is needed to integrate water planning tools more effectively with those of urban planning. 55.

Reducing land development while improving access to housing

The housing situation in France is critical and getting worse. In the 2025 edition of its report on inadequate housing, the Fondation pour le Logement des Défavorisés (ex-Fondation Abbé Pierre) points out that 350,000 people are homeless in the country. Demand for social housing is rising steadily (2.7 million households in 2024), while allocations are falling: 393,000 in 2023, some 100,000 fewer than in 2016. In all, 4.2 million people are inadequately housed in France, and 12 million are in a fragile housing situation. 56.

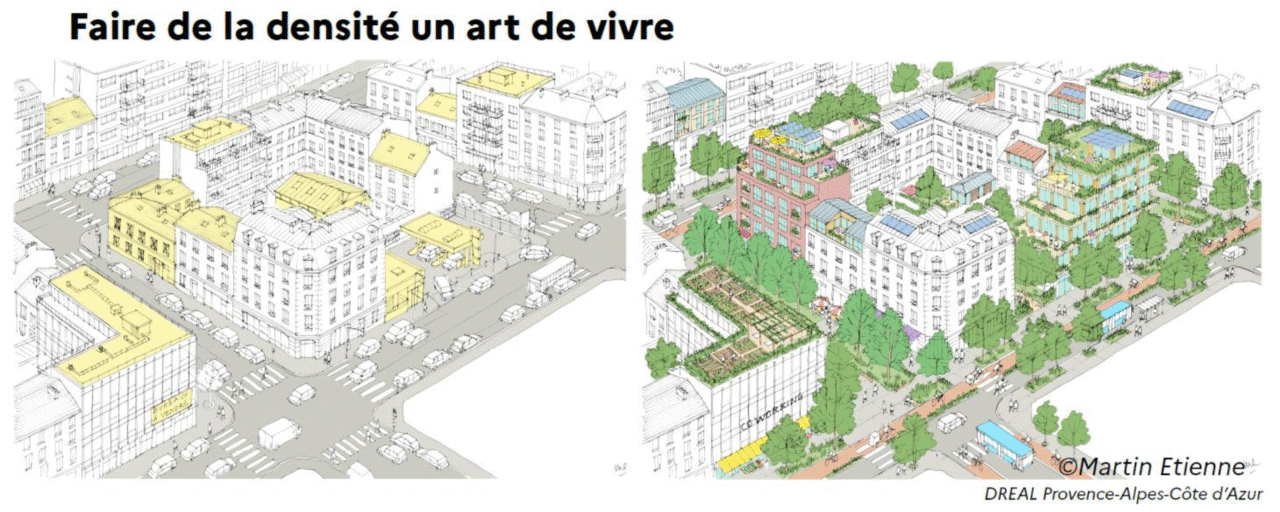

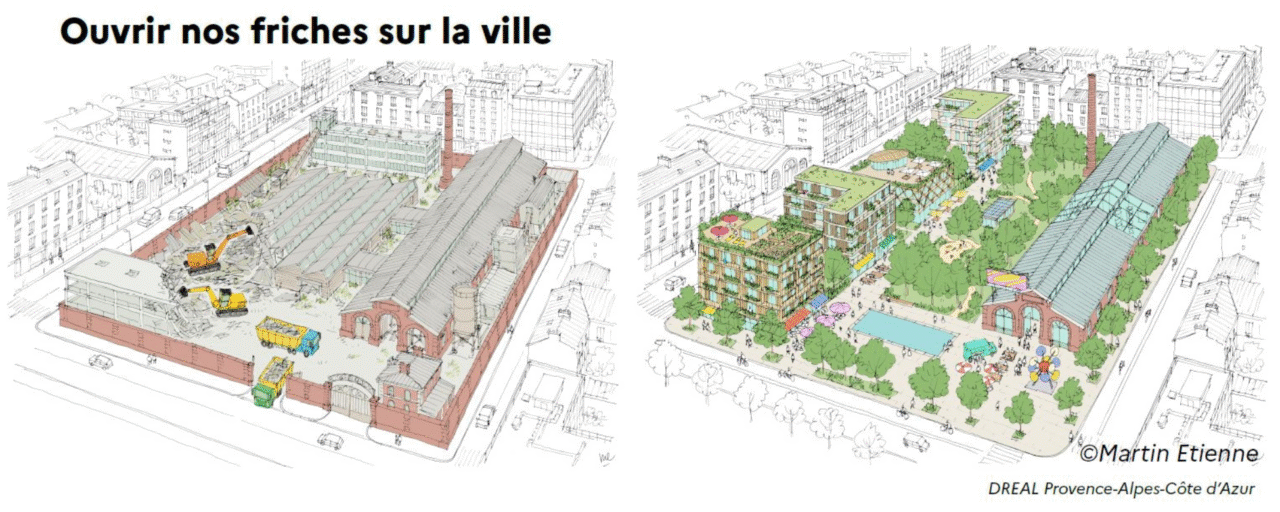

The ZAN objective of reducing land artificialisation is sometimes presented in opposition to the need to increase access to housing. However, reducing land artificialisation does not mean halting housing production. Depending on the region, there are a number of levers available.

- Optimize the use of existing buildings by combating vacancy and under-occupancy (of homes and offices), reducing the proportion of second homes and more effectively regulating the rental of furnished tourist accommodation in areas where demand is high.

- Intensify urban renewal to build new homes in already urbanized areas, while improving the living environment for all.

- Build new housing on the tens of thousands of hectares of land still available for development under ZAN, with priority given to multi-family housing.

These levers were presented in detail and accompanied by some forty proposals in a report published in March 2024, the result of collaboration between the Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme and the Fondation pour le Logement des Défavorisés, entitled. Making a success of ZAN by reducing inadequate housing: it’s possible! .

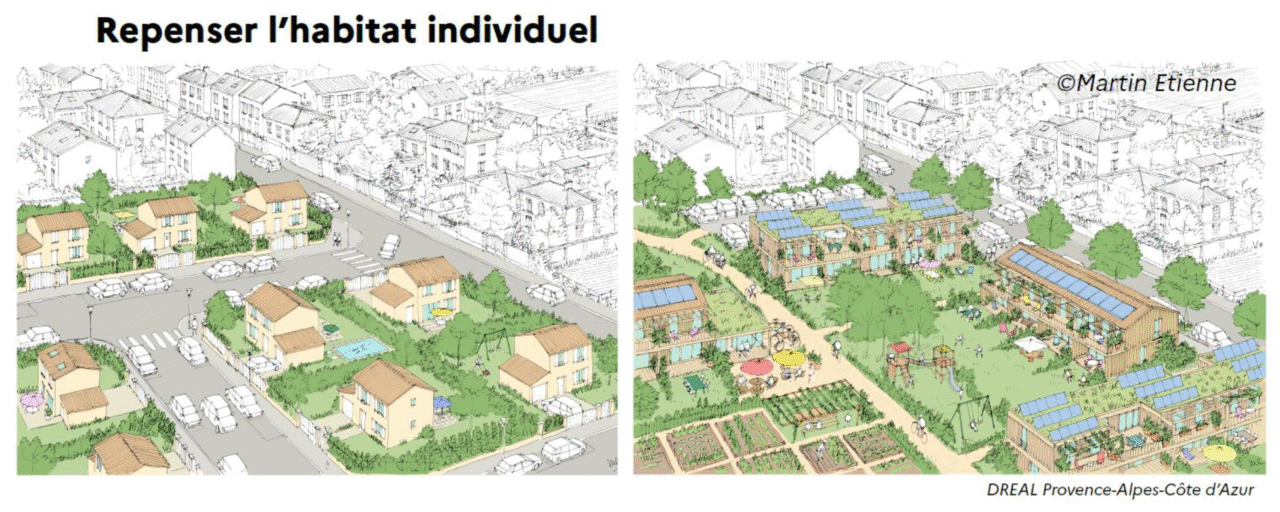

DREAL PACA has produced a series of illustrations to show what it might look like to implement various land-saving levers to reconcile the reduction of artificial development with housing production.

Conclusion

By incorporating the fact that land is available in limited quantities and that urbanized areas cannot expand endlessly into law and regional planning, Net Zero Artificialization is one of the first policies to directly integrate the notion of planetary limits and the finiteness of a resource: in this case, the space available for urban development, and land as a living ecosystem.

To put this into practice, we need to radically rethink the way in which we conceive land-use projects and the economic models we use for development. What’s more, the issue of land use, which cuts across a number of economic sectors, is necessarily a complex one, creating competition and friction over access to land. This partly explains the fierce opposition ZAN has faced and continues to face.

Nevertheless, local authorities have been working hard since 2021 to make progress in implementing the ZAN, with the first step being to incorporate targets for reducing artificialization into regional plans. Today, local authorities are not waiting for ZAN to be unraveled, which would mean wiping out all the work done to date, but for answers concerning economic, fiscal and territorial engineering tools, to speed up their action, develop more virtuous projects and reduce artificialization.

Yet certain political players continue to seek to neutralize ZAN, by emptying its legal architecture of any binding scope. These setbacks waste precious time and hectares of land. At a time when the consequences of climate change are intensifying, it is a historic mistake to break the momentum of strategic territorial planning – which involves protecting agricultural land, speeding up urban renewal, rethinking how we deal with floods and droughts, rethinking mobility and so on. – is a historic mistake.

Find out more

Guides and reports

- Four leaflets published by the French Ministry of Ecology on ZAN implementation for local authorities (2023)

- It’s possible to make a success of ZAN and reduce inadequate housing! Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme – Fondation pour le Logement des Défavorisés (2024).

- ZAN financing: closer to local needs! Foundation for Nature and Mankind (2024)

- Let’s stay ZAN: Towards a rewarding tax system, WWF France ( 2025)

Works

- Le Zéro Artificialisation Nette: de la contrainte à l’opportunité, Marion Michel, Walter Salamand, Territorial Editions (2024)

- La ville stationnaire: comment mettre fin à l’étalement urbain, Philippe Bihouix, Sophie Jeantet, Clémence De Selva, Actes Sud (2022)

- Let’s repair the city! Propositions pour nos villes et nos territoires, Christine Lecompte and Sylvain Grisot, Apogée (2022)

- Redirection urbaine : enquête dans la fabrique des territoires résilients, Sylvain Grisot, Apogée (2024)

- Soils and their formation in temperate climates, Planet-Terre (2020). ↩︎

- The first decentralization law was promulgated on March 2, 1982, and supplemented by a second law on July 22, 1982. This was followed by 25 laws on the subject (and some 200 decrees) until 1986. Together, these texts constitute what has been called “Act I of decentralization”. To find out more, see the history of decentralization on the French government website. ↩︎

- SCoT: schémas de cohérence territoriale; PLU: plans locaux d’urbanisme. To find out more about urban planning documents , see the box “Overview of territorial planning and urban planning documents”“”. ↩︎

- As part of PLU sustainable development projects (PADD), cf. Article L123-1-3 – Code de l’urbanisme. ↩︎

- Agences d’urbanisme Rhône-Alpes, Modération de la consommation d’espace et lutte contre l’étalement urbain, November 2014. ↩︎

- Article 69 – LOI n° 2016-1087 du 8 août 2016 pour la reconquête de la biodiversité, de la nature et des paysages. ↩︎

- Convention Citoyenne pour la Climat, full report, Chapter “Se Loger” – objectif n°3, page 295. ↩︎

- ENAF stands for Espace Naturel Agricole et Forestier. To find out more about the consumption of ENAF and the difference with the notion of soil artificialisation , see section 2.1. ↩︎

- The principle of conformity prohibits any difference between the higher and lower rules. The principle of compatibility is more flexible, since it implies only that the lower rule must not prevent the implementation of the higher rule. The principle of taking into account or taking into consideration is the least restrictive. It implies that the inferior rule must respect the superior rule, at least in its most important aspects. ↩︎

- Some regions are not covered by an SRADDET, but do have a specific regional planning document: the master plan for the Île-de-France region (SDRIF-E), the Schémas d’Aménagement Régionaux (SAR) for overseas regions, and the Plan d’Aménagement et de Développement Durable de la Corse (PADDUC). ↩︎

- Le SCoT modernisé, Edition 2022, DGALN – Fédération des SCoT. ↩︎

- The planning document for the Ile-de-France region is the SDRIF-E (Schéma directeur de la Région Ile-de-France), for Corsica the PADDUC (Plan d’aménagement et de développement durable de Corse) and for the French overseas territories the SAR (Schéma d’aménagement régional). ↩︎

- What trajectory of land sobriety for Ile-de-France? ZAN, Revue Urbanisme, 2024. ↩︎

- De la loi Climat et résilience à la loi ZAN : le cap de la sobriété foncière, entre avancées et questionnements, Institut Paris Région, 2023. ↩︎

- The 2021 Climate and Resilience Act provided for a tighter timetable, but the 3DS Acts of February 21, 2022 and then the ZAN Act of July 20, 2023 extended the deadlines for incorporating land-saving objectives into planning and urban development documents. ↩︎

- See the version of article R 4251-8-1 of the Code général des collectivités territoriales in force following the SRADDET decree. ↩︎

- Climate and resilience decrees (ZAN): AMF appeals to the Conseil d’État, Association des Maires de France website. The appeals were lodged on June 28, 2022. ↩︎

- Decision no. 465343 – Conseil d’État. ↩︎

- Légifrance, Décret n° 2023-1097 du 27 novembre 2023 relatif à la mise en œuvre de la territorialisation des objectifs de gestion économe de l’espace et de lutte contre l’artificialisation des sols, Article 1er, II, 1°, a). ↩︎

- The principle of regional-scale projects was introduced by the SRADDET decree of April 2022. See section 2.2.1. ↩︎

- Arrêté du 31 mai 2024 relatif à la mutualisation nationale de la consommation d’espaces naturels, agricoles et forestiers des projets d’envergure nationale ou européenne d’intérêt général majeur – Légifrance, Article 1. ↩︎

- Mapping national projects | Land artificialisation portal. ↩︎

- See L’opération d’intérêt national (OIN), on the Cerema website (10/06/2022). ↩︎

- Order of May 31, 2024 relating to the national mutualization of the consumption of natural, agricultural and forestry areas by national or European-scale projects of major general interest. Appendix II provides an indicative, non-exhaustive list of projects that could be included in Appendix I if the order is amended. ↩︎

- Statistics – Géoportail de l’Urbanisme. ↩︎

- Also via amendments to the “Green Industry” bill, debated at the same time. ↩︎

- See De la loi Climat et résilience à la loi ZAN : le cap de la sobriété foncière, entre avancées et questionnements, Institut Paris Région, 2023 and Loi du 20 juillet 2023 visant à faciliter la mise en œuvre des objectifs de lutte contre l’artificialisation des sols et à renforcer l’accompagnement des élus locaux, Vie Publique, 21/07/23. ↩︎

- P-A Maron (Inrae), Lionel Ranjard (Inrae), Philippe Billet (Université Lyon III), Thomas Uthayakumar and Rémi Guidoum (Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme), Améliorer le suivi de l’artificialisation par une évaluation scientifique de la qualité écologique des sols, July 2023. ↩︎

- See the data sheet Large-scale land use (OCS GE) | Data sheet | Land artificialisation portal, and the Methodology for producing OCSGE data | Land artificialisation portal. ↩︎

- See Zéro Artificialisation Nette – Fascicule 1: définir et observer (2023), page 23. On the obligation to renaturalize, see also our Infosheet La provision pour démantèlement au service de l’écologie. ↩︎

- Objective ZAN: how to keep score, MNHN, 02/05/22. ↩︎

- Ecological networks, a conservation strategy to reconcile ecological functionality and land use planning, Géoconfluences , 2022. ↩︎

- Exemption for certain ground-mounted photovoltaic or agrivoltaic installations | Land artificialisation portal. ↩︎

- See a summary on vie-publique.fr. ↩︎

- Relaxation of ZAN: in a letter, the authors of the text accuse François Bayrou of “immobilism”, Public Sénat, 23/05/2025. ↩︎

- ENAF stands for Espace Naturel Agricole et Forestier. To find out more about the consumption of ENAF and the difference with the notion of soil artificialisation , see section 2.1. ↩︎

- See L’occupation du sol entre 1982 et 2018, Agreste, Les Dossiers, 2021 and L’occupation du territoire en 2022 Enquêtes Teruti 2021-2022-2023, Agreste, la statistique agricole, 2024. Please note that the survey methodology was modified in 2024. Long series of data prior to the methodological change (1982-2022) are available online. ↩︎

- Agreste Primeur, Land use, Issue 326, July 2015. ↩︎

- Agreste, Les Dossiers, L’occupation du sol entre 1982 et 2018, April 2021. ↩︎

- Cerema, L’artificialisation et ses déterminants d’après les fichiers fonciers, April 2020. ↩︎

- The evolution of the agricultural population from the 18th century to the present day – Persée. ↩︎

- Consolidation is a land operation aimed at grouping plots together to make it easier to farm with machinery. ↩︎

- Farmers: fewer and fewer, more and more men – Insee Focus – 212. ↩︎

- Insee Première – Population projections to 2070 Twice as many people aged 75 or over as in 2013. ↩︎

- Evaluation of tax and non-tax obstacles to generational renewal in agriculture, Inspection générale des finances,2024. ↩︎

- Renouveler les générations, INRAE, 2025. ↩︎

- Nos propositions pour lutter contre la concentration des terres, Terre de liens,2023. ↩︎

- Plans locaux d’urbanisme – Des arguments pour agir en faveur du climat, de l’air et de l’énergie Cerema, 2018. ↩︎

- Fabrique de savoirs – The unprecedented decline of the earth’s carbon sink CEA, 2024. ↩︎

- Annual report 2024, executive summary Haut Conseil pour le Climat, 2024. ↩︎

- See the Explore2 project – The future of water, by the Office Français de la Biodiversité, 2021-2024. ↩︎

- Le Monde, La sécheresse oblige des maires du Var à suspendre les permis de construire : ” Le dérèglement climatique devient concret pour nous “. ↩︎

- Préfet du Var, Courrier du 10 mars 2023, “Ressource en eau et urbanisme sur le territoire de la communauté de communes du Pays de Fayence”“”. ↩︎

- The Toulon Administrative Court confirms the cancellation of a building permit on the grounds of water scarcity. ↩︎

- Guide “Ressource en eau et milieux aquatiques : quelle intégration dans les documents d’urbanisme?”, France Nature Environnement PACA,February 2020. ↩︎

- In vulnerable situations: occupants of a co-ownership in difficulty, tenants with unpaid rent or service charges, modestly overcrowded people, modestly overcrowded people who have suffered from cold because of fuel poverty, people making excessive financial efforts, people in housing unsuitable for their disability. ↩︎