This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

From the end of the 1990s, under the impetus of the European Union, France’s electricity sector was gradually liberalized, moving from a public monopoly to a competitive market. Thirty years on, this opening up to competition is proving to be rather unusual. Indeed, the generation, transmission and distribution chain has changed very little. 1 . Most of the liberalization has therefore concerned the final segment of the sector, i.e. electricity supply (i.e. offer design and customer relations). This fact sheet focuses on the analysis of the opening up of this segment (also known as the “retail market” for electricity) to competition for residential customers.

Opening up electricity supply to competition was, of course, a complex undertaking. The incumbent operator, EDF, enjoyed a massive competitive advantage, since it controlled most of France’s electricity production and initially supplied all consumers. From an industrial economics perspective, barriers to market entry are said to be very high: new companies wishing to enter the market are at such a disadvantage that it is impossible for them to develop an offer on their own.

From then on, all EU and national regulations governing this opening up to competition have revolved (and continue to revolve) around the following objectives: allowing potential entrants access to the market, and then ensuring their economic viability. In a way, it’s a question of ensuring an electricity supply market without any barriers to entry over a long or even infinite period of time.

This is a very singular point, as most economic sectors have de facto barriers to entry (through innovation, ownership of productive assets linked to past investments, commercial creativity, etc.). The desire to remove them through regulation may be understandable during the transitional period of market emergence, but it is much less justifiable in the long term.

We’ll show that this configuration has produced “a Far-West market that’s constantly emerging”, with dozens of electricity suppliers entering the market without any differentiation of supply. What’s more, no tangible segmentation has taken hold, probably due to the absence of technological breakthroughs. As a result, competition on the market is mainly based on toxic processes.

If you don’t have a detailed knowledge of the electricity sector, we recommend that you read the appendix, which will shed light on terms such as wholesale market, alternative suppliers and incumbent suppliers.

Opening up the electricity market to competition concerns a small segment of the industry

Electricity supply: a business essentially limited to billing and customer service

Describing the opening up of the retail electricity market in an obscure institutional meeting, a senior official recently said that it was a matter of enabling “a private individual to speak to a customer service other than that of EDF”.

It’s a fair presentation, because let’s not forget that while the opening up of the market is the subject of much debate, and involves a gigantic and fragile scaffolding, in reality it only concerns a very small segment of the industry. It concerns (almost) nothing to do with production, and nothing to do with transport and distribution. It therefore concerns only a relatively small version of the supply chain, namely tariffs, offer design, customer service and billing. We shall see that, for structural reasons, suppliers have similar tariff levels and designs (see part 2 on the absence of tariff competition). So it turns out that this major project to open up the electricity market essentially concerns customer service and invoicing, which in itself is very modest.

Electricity supply is not comparable to the food superstore business

This eliminates a comparison that is often used, but which is completely false: we could distinguish between the production and supply of electricity in the same way as we would distinguish between production and distribution in the food sector, for example.

The allegory doesn’t hold water, because in electricity, alternative suppliers are not distributors: they don’t intervene in the electricity distribution service provided to the consumer (ensuring line commissioning and continuity, metering consumption).

A supermarket, on the other hand, offers much greater added value than an alternative electricity supplier: logistics, sales facilities (including cut-size shelves, for example), customer service, invoicing, and all this in a multi-product business that offers much greater differentiation than a simple single- or dual-product supply (as gas supply follows the same logic).

Last but not least, let’s put to rest the common-sense remark that “opening up the electricity market means considering that you don’t have to be a producer to be a supplier”. With 80 suppliers (40 for private customers) who are (virtually) non-producers, the objective has certainly been achieved!

Except that the problem isn’t that non-producer distributors are allowed to flourish here and there (in themselves that’s understandable), but the fact that we now have a very specific industry structure: a very dominant generation company (EDF), a public transport-distribution monopoly (RTE and Enedis) and …. 80 electricity suppliers, 78 of whom are in France. 2 have virtually nothing to do with the upstream sector.

Lack of price competition between market offers

Alternative suppliers and their brokers commonly use the term “regulated sales tariff replication strategy”.

Insofar as one company (EDF and its subsidiaries) is ultra-dominant over most of the production chain, the determination of the selling price depends very essentially on the evolution of its production costs and its margin policy. To avoid the classic pricing effect of a private monopoly 3 (and to avoid over-exposing consumers to market fluctuations), a regulated sales tariff has been introduced.

The 39 other suppliers (for private customers) have no means of production and no control over cost price. Their policy in this area consists of :

- to claim an equal footing with EDF by having guaranteed access to nuclear power: this is the famous regulated access to historical nuclear power (ARENH), which obliges EDF to sell part of its production to its competitors at a price of €42 MWh (see box);

- when the wholesale price is less than 42€ MWh do not request ARENH supply;

- to hedge on the market in order to have a fairly predictable cost for electricity supply, or not to hedge in order to keep a tariff advantage when wholesale prices are low;

- manage their internal costs in a highly optimized way (even if this concerns only a very small part of the sector, this is what can enable a tariff discount relative to EDF).

Understand how ARENH and the capping mechanism work?

ARENH is a system that obliges EDF to sell up to 100 TWh of its production to alternative suppliers each year at a fixed price of €42 MWH, which is supposed to represent the production costs of historical nuclear power.

In November, alternative suppliers submit their requests for ARENH volumes for the following twelve months to the Commission de régulation de l’énergie. They do so on the basis of their customers’ forecast consumption during low-consumption hours (known as “ARENH Hours”).

If overall demand exceeds the 100 TWh ceiling set by law (as has been the case since 2019), the Commission de Régulation de l’Energie (CRE) must capped the ARENH volumes: after examining the validity of requests, it allocates the available 100 TWh proportionally. For example, during the November 2021 auction for the 2022 delivery year, the CRE received around 160 TWh of ARENH requests: after capping, each alternative supplier was allocated 62.37% of the volume requested, and will have to purchase the missing volumes directly on the wholesale market.

Source More information on the EDF website or on the CRE website.

It is easy to see that the tariffs charged by these suppliers are a “variation around the regulated tariff”.

The regulated sales tariff (TRV) should correspond more or less to the actual cost of production for the French electricity industry. 4 . Alternative suppliers, relying de facto on this sector, therefore have no other pricing model.

The variation “around” the TRV depends on two main variables:

- wholesale price levels and supplier coverage,

- nuclear access granted collectively to these suppliers.

This model could change if nuclear power ceased to be cheaper than other sources of generation (particularly renewable energies). Even in this scenario, these suppliers are low-volume producers, and therefore remain dependent on a wholesale market whose extreme volatility was demonstrated in winter 2021. It is therefore necessary to have strong financial reserves to be able to hedge.

If we consider the first variable, suppliers can offer discounts compared with the regulated sales tariff (of the order of 10%) when wholesale prices are low and if they have little hedging. When wholesale prices are high, it’s harder for them to offer discounts, and their prices will be much higher than the TRV if they have little or poor coverage.

It’s easy to see that the most common hedging strategy is to try to “replicate” the TRV as consistently as possible, which amounts to making the TRV less a small discount of around -5%.

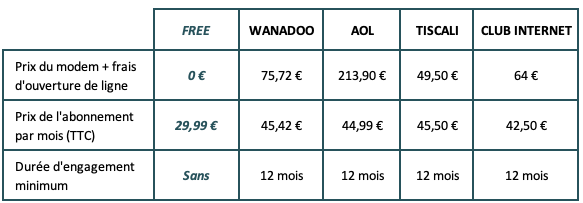

The graph below from CRE’s market observatory concerns the years 2015-2019, when wholesale market prices were very low and fairly stable. These were by far the most favorable years for price discounts. We can see that the bulk of the offers are between – 0% and – 7% of the TRV. This is typically a “tariff replication” market.

Alternative suppliers’ offers cheaper than the regulated sales tariff 2015-2019

Source The functioning of the French retail electricity and natural gas markets – report 2018-2019 – Commission de régulation de l’énergie.

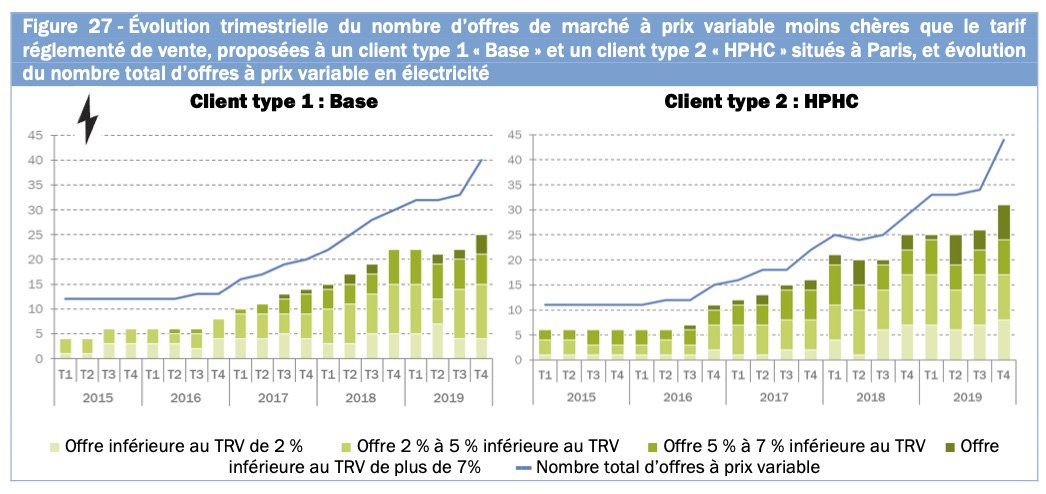

By way of comparison, we reproduce below FREE’s price list when it entered the Internet access market in 2002.

The discount was over 40% and, developed in triple play (telephone, internet, television), it has become the norm.

This is an example of a market opening that creates not “a replica” but price competition.

It has to be said that alternative suppliers have at some point introduced price differentiation (much more so in gas than in electricity), offering fixed prices for one to three years (the longest terms being in gas).

This guarantee, which may have been protective for some customers in the first year of the wholesale market crisis, is in fact linked to a market hedging strategy. This should be emphasized as an added value, while noting that this process took place during the blessed era of low and fairly stable wholesale prices.

There’s no guarantee that this “differentiation segment” will survive the crisis that begins in 2021. It should be noted that in winter 2021, two players (albeit of relative size) 5 have called into question their commitment to a fixed gas price.

Very little non-price differentiation of market offers

The benefits of competition in supply could lie in alternative suppliers’ ability to 6 to offer innovations, which can be likened to the economics of variety.

The economics of variety

Variety economics is a branch of economics that studies the fact that a company segments its offer into different products in order to satisfy heterogeneous consumer preferences. For example, a car manufacturer offering different ranges of cars. An insurer offering different levels of risk coverage and different options (with or without a glasses package, dental package in the case of health insurance).

This economy of variety has failed to develop in the electricity supply sector for three main reasons

- First of all, in a system where electricity prices (excluding taxes!) were among the lowest in Europe (but higher than in North America), it would probably have taken a breakthrough innovation to create the groundwork for real differentiation (the digital breakthrough, for example, enabled triple play at 29.99 euros with a box _ see table above). It’s hard to overstate the extent to which this lack of disruptive innovation largely obviates the chances of an interesting competitive dynamic when the market opens up.

- Secondly, the electricity sector doesn’t lend itself very well to the economics of variety, because it’s an essential consumption, not a recreational one. Basically, the consumer expects a delivery of electricity at a certain level of expenditure, and that’s about it. 7 . We can’t graft onto it any recreational use, subjective affection (the taste of a product) or aesthetic aspects (a sexy electron?), even if some are trying a little with customer applications. The potential for differentiation is not nil, as we shall see, but it is nonetheless very limited.

- Finally, liberalization meant moving from a state monopoly to a model in which the incumbent operator (responsible for the bulk of electricity production and supply) competed with “virtual” operators (since they had no physical link with production, and therefore had to buy electricity from producers in order to supply it to end customers).

By instituting the ARENH system, the 2010 Nome law gave these operators a foothold by giving them access to electricity produced by EDF at a guaranteed price. At the same time, however, the law required them to develop their own means of production.

They didn’t, believing that it was in their interest to stay connected as much as possible to EDF’s nuclear power and, for the rest, to buy on the wholesale market. Above all, while being an electricity supplier mainly involves creating a digital start-up, it’s much more difficult to improvise as an energy supplier. It really isn’t the same business, and it’s night and day in terms of complexity and risk-taking.

Many institutional players and mainstream market observers tend to regard the fact that these suppliers don’t invest in production (because EDF’s production was sufficient for French consumption needs) as very natural. This theoretical viewpoint underestimates the practical consequences: from the moment you produce (virtually) no electricity, transport none and distribute none, you have very little room for maneuver when it comes to diversifying your offer. In fact, you don’t sell “your product”, “your supply chain” or “your transmission method”…

Taken in isolation, it’s likely that none of these factors is a clear-cut barrier to supply differentiation. But the accumulation of these factors, which are quite structural, does explain the very frustrating nature of this market in terms of innovation and differentiation.

We’re going to take a closer look at some of the innovations introduced to the market, often highlighted by the French Energy Regulatory Commission as a sign of the benefits of liberalization.

Green electricity offers: paper labels for virtual operators (and electrons)

Green electricity offers have developed at rates close to those of non-green offers.

A glance at the Energy Ombudsman’s comparison tool gives an idea of the offers on the market, and highlights a singular fact: “green” offers are proliferating. They all have similar tariffs, themselves very close to the tariffs of non-green offers, which are also close to the regulated sales tariff. In fact, there are a great many offers on the market, but they fall into two categories (non-green/green offers; fixed-price/variable-price offers) and more or less all have the same price.

It’s also worth noting that there are so many green offers, and so few guarantees, that they continue to be sold in the same way as a conventional offer, i.e. by comparing their discount with the regulated tariff (see image below).

Can you imagine an organic product being sold in this way? No, because organic products can offer real added value.

It’s surprising to see so little price differentiation between green and non-green electricity, when you consider that in other markets, the ecological “mark-up” is often pronounced (a good 30% for organic food products, for example). One might conclude that renewable energies are as competitive as the conventional electricity mix, but in fact this is not the way to resolve this particular debate.

The explanation is much simpler and perfectly logical.

Green and non-green offers are priced the same, because basically… we’re selling pretty much the same thing!

There is a single generation system comprising around 70% nuclear, a fraction of hydro, a fraction of other renewables and a fraction of fossil fuels. EDF, the former historical monopoly, accounts for 80% of production. Some alternative suppliers are also producers (mainly Engie and Total Energie). Finally, there are also a few non-supplier producers (Neoen for solar power, for example).

The electricity generated is transmitted via a single network 8 transmission and distribution network. In the end, everyone receives the same electricity.

Above all, the development of green offers, through the system of guarantees of origin, is in no way responsible for an increase in renewable production.

In short, the number and market share of green offerings have grown significantly in the space of a few years, even though the share of renewable energies in the electricity mix has grown only slightly.

Green offers and guarantees of origin (GO)

Any non-state-supported producer of renewable electricity can obtain a certificate of guarantee of origin (GO) attesting to the volume of green electricity injected into the grid, and then sell it on a market parallel to the electricity market. Green offers simply mean that the electricity supplier has purchased GOs corresponding to the volume of electricity sold (irrespective of the type of producer from whom it purchased this electricity). Some green offers provide additional guarantees (for example, the purchase of GOs and electricity from the same producer).

Here are a few details:

1/ Apart from self-generation, there is no guarantee that consumers are actually buying green electricity: electrons cannot be traced, and purchase/sale contracts are not linked to the physical circulation of electrons.

2/ As the CRE notes, the GO system “applies to existing installations, particularly hydroelectric ones, which does not ensure that a green offer contributes to the development of new renewable production facilities”. Thus, in 2019, 91.6% of GOs used to certify the “green” origin of consumption in France were issued by hydropower facilities (including around 1/3 outside France). The majority of green offers are therefore nothing more than a “rebranding” of renewable energies that already existed.

3/ Renewable energy producers whose financing is supported by the State must transfer the GOs they obtain to the State. The State can then auction them off (the revenues thus obtained contribute to the budget’s energy transition allocation account).

Source More information in the dossier on green electricity offers – CRE Report 2018-2019 on the retail electricity and gas market p. 141 ff.

The development of green electricity offers therefore raises important reservations

The first is the defense of the general interest. A well-established principle of ecological policy is that an approach (commercial offer, investment, etc.) can be considered “green” if it induces additionality.

Additionality is the characteristic of a measure whose ecological added value is added to or complements an existing action program. In France, a compensatory measure must be additional both from an ecological point of view, i.e. it must provide an ecological gain in relation to the initial state; and in relation to public and private commitments, i.e. it must go beyond the actions that the State, local authorities or other project owners have already committed to implementing.

The CRE itself notes that the ADEME label, which is due to come into force shortly, does not meet these criteria. “CRE therefore considers that the label proposed by ADEME is not a complete response to the issues raised by green offers. In particular, labelled offers based on publicly-supported facilities will not contribute to the development of renewable energies in France any more than any other conventional supply offer.” 9

The second concerns respect for the goodwill of consumers who subscribe to this type of offer thinking they are making a “specific” gesture for the ecology, which is not the case (they consume electricity like everyone else and don’t contribute any additional financing). There may even be a counterproductive effect insofar as this purchase of green electricity may lead consumers to think that they have “done their bit” from an ecological point of view (which is not the case) and that they therefore don’t need to make far more crucial efforts in terms of energy efficiency.

As one solar producer noted in 2019 10 about a quarter of these certificates of origin correspond to Norwegian hydroelectric production, and some are even located in Iceland, which is not connected to continental Europe!

The second non-price differentiation concerns peak-rate offers.

With remote metering (known as “Linky”), suppliers can offer tariff discrimination that is finer than the classic “off-peak, peak” time slots, and more marked in terms of discounts (-50% in super off-peak, -30% at weekends). At least their principle is more viable and less intrinsically deceptive than that of “green” offers.

While it’s too early to draw up an assessment of these “peak offers”, it should be noted that, as far as we know, there has been no significant development of this type of offer for private customers outside France. The interest of this type of offer for large professional consumers is obvious and well known. 11 but it seems difficult to transpose to private customers, as the financial gains for the latter are too low given the complexity of setting up the offer.

What’s more, from the point of view of the general interest, we may question the ability of decentralized market offerings to change behavior globally. Indeed, we are faced here with an anti-selection syndrome that is well known in the insurance sector. Consumers have more or less risky profiles. Let’s imagine that a professional launches an insurance product offering a very low rate for a consumer with an objectively low-risk insurance profile. Does the launch of this offer modify the overall risk level of the population, or does it simply induce a migration of low-risk profiles from one offer to another? Most probably, the second option is the most common.

The same applies to peak pricing. For the most part, it probably doesn’t modify the average consumption curve (i.e. the peak profile), but simply reallocates the different profiles between the different offers and suppliers.

Dynamic electricity pricing: when the market doesn’t dare to differentiate, the European Commission imposes it!

The story of the introduction of dynamic pricing in Europe is a singular one. In itself, dynamic pricing is an interesting and virtuous principle.

On the one hand, demand is concentrated too much on peak periods, which poses ecological and financial problems, as well as the risk of power cuts.

On the other hand, wholesale market prices vary considerably and are higher during peak periods.

The principle of dynamic pricing involves indexing the tariff paid by the consumer to the wholesale market price (a variable price) and sending him the daily tariff schedule 24 hours in advance so that he can adjust his consumption (this is called “demand response”). 12 .

Dynamic pricing presents major risks for consumers

The principle is a virtuous one, but it’s obviously suited to optimizing professional operators who can adjust plant operation to this pricing grid.

With the exception of very special cases (which boil down to electric car owners who can activate recharging at the time of their choice), domestic users have very little room for manoeuvre when it comes to adjusting their daily consumption. What’s more, we’re exposing these individuals to a very pronounced risk because, to put it simply, there’s nothing more volatile than the wholesale electricity market. As a result of a climatic incident in February 2021, some Texas consumers who subscribed to these offers received a monthly bill of several thousand dollars. 13 .

The risk is such that regulatory stakeholders are suggesting that the regulation of savings products in the wake of the financial crisis be used as a model to standardize the sale of these dynamically-priced offers (basically, “beware: the dynamic rate of the past does not prejudge the dynamic rate of the future”, “tick the box to certify that you are aware of all this is very risky”, etc.). tick the box to certify that you are aware that all this is very risky”, etc.).

Commission requires suppliers to propose dynamic pricing offers

From a more structural point of view, it’s easy to see that this kind of tariff variability is the exact counterpoint to the French system, which, thanks to the hydro-nuclear tool, is designed to deliver a stable price. We are therefore introducing volatility into a sector that, in France, was not volatile, and financial risk into a sector that we do not want to be risky.

There was a rare consensus among institutions, suppliers and consumer associations that this type of offer was not at all suited to the French situation (and might be somewhat appropriate in some European countries, notably those without electric heating and with fairly stable wholesale prices (as in Scandinavia, for example). In fact, the French market didn’t offer this type of service to private customers because no one wanted to.

Be that as it may, the European Commission, in a recent provision 14 has made it compulsory for any electricity supplier with over 200,000 customers to have this type of offer. This is a very curious case where, faced with the disinterest of market players in a product configuration, the regulator imposes it.

As soon as the wholesale market exploded in October 2021, the few existing offers disappeared. The attempt to highlight these offers at least has the merit of demonstrating just how poorly the logic of the commodities market (with a wholesale market, etc.) applies to the supply of electricity to private individuals: if we’re building a system to be stable, there’s no point in introducing volatility at any cost. Such a logic only works with players who are able to optimize their consumption on an ongoing basis, and therefore have specialists dedicated to managing this consumption, which is of course not the case with households.

It also highlights the excesses of “market building” and “market design”, which in the electricity sector have created an industry of expertise, consultants, workshops and symposia. So much so, in fact, that we’re now creating offers, and the market design that goes with them, even when nobody wants them, in order to talk about them in workshops.

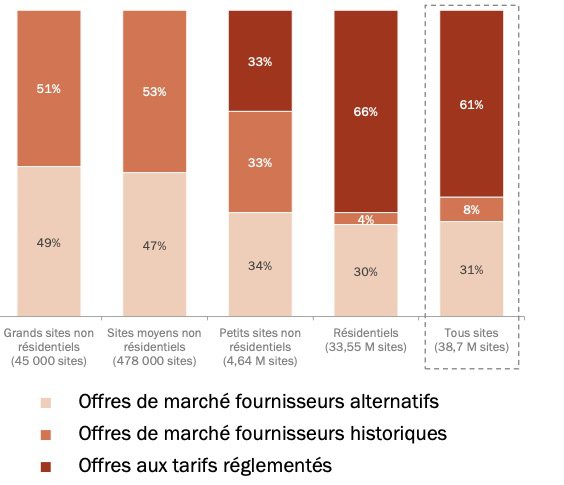

As a transitional measure, the best demonstration of both consumers’ lack of interest in this opening and the market’s lack of differentiation is the fact that EDF has retained a market share of around 70% of residential sites (largely at the regulated tariff).

Breakdown of electricity consumption sites by type of offer at June 30, 2021

Source Observatoire des marchés de détail du 2e trimestre 2021 (p.10) – Commission de régulation de l’énergie (CRE)

Such predominance, after 15 years of market opening and 5 years of very low wholesale prices (i.e. a very fertile ground), is not so much flattering for EDF as illustrative of a market struggling to offer added value.

Lack of real differentiation between electricity offers: toxic differentiation

What we describe in this section has a very clear origin:

- 40 suppliers for private customers all on the starting line;

- a regulatory framework designed to level the playing field as much as possible;

- the absence of tangible differentiation potential.

In this context, the only way to gain market share is to resort to rather savage practices or to take risks. While not all operators resort to these practices, they are all too widespread in the sector. In fact, they correspond to the following sequence:

- when wholesale prices are low (the “go go years” period), consumers are harassed and deceived;

- When wholesale prices are high and/or volatile, suppliers who were poorly covered break or twist contracts to raise prices;

In times of low wholesale prices: harassment or deception of the consumer

The liberalized energy supply sector suffers from a syndrome with which consumer associations are all too familiar: when there is little or no “tangible” differentiation, this is reflected in deceptive aspects or aggressive commercial practices.

Let’s take a closer look at what canvassing actually means. In many cases, it is based on two levers:

- intimidation, often of a physical nature, to force people to subscribe: young adult canvassers who intimidate elderly people;

- the use of deception, often in particularly vile ways.

Aggressive door-to-door canvassing is particularly prevalent in the energy sector, for the reasons given above (little tangible differentiation), but also because the canvasser uses trickery to obtain customer data (bills, bank details, meter details) to force a subscription. It therefore takes on a more physical and malicious dimension than other forms of canvassing involving simple telephone reminders.

A typical example of aggressive and misleading canvassing

In December 2019, on his way home, Mr D noticed two men ringing his doorbell. After telling them that he was a tenant in the apartment, a third man approached him, showing him a business card. He told him he was an agent for a company that supplied gas and electricity. He went on to explain that the suppliers had to apply a discount on the contribution tarifaire d’acheminement (CTA). They were there to check with consumers that this reduction was actually being applied by their supplier. To prove this charge, the canvasser showed Mr D invoices that had already been sent to him. Mr D was happy to have his bill lowered too, so he texted him his invoices, not seeing what could be done without his consent. A few weeks later, he received a welcome letter from a new supplier stating that he would receive his bill the following month. Mr D then contacted his supplier, who confirmed that his contracts had been cancelled. However, he had not agreed to this.

Source Testimony of abusive canvassing received by CLCV (quoted in the press kit – Plaidoyer pour un retour au monopole sur le marché de détail de l’électricité, 2021)

Insofar as consumers can switch back to their original operator free of charge, the issue is not so much financial as – and we weigh our words carefully – related to the trauma caused by this type of canvassing. The people canvassed have simply been deceived and/or intimidated in their own homes, and they are scarred by it.

One of the characteristics of aggressive canvassing is its consistency over time in the electricity sector. Indeed, while it exists in other fields, aggressive canvassing occurs in waves at particular times specific to the sector. For example, when a market first opens up and the first offers are developed (e.g., triple-play subscriptions in the telecoms sector in the mid-2000s), or when the context changes (e.g., when the government grants a tax credit for a particular type of work). Quite often, aggressiveness tends to diminish in the aftermath of this wave, under the combined effect of actions by consumer associations and fraud control authorities, and because the market is maturing.

This cycle effect does not seem to apply to operators in the energy sector. Despite numerous court rulings and recurrent criticism from stakeholders, this practice persists (only the door-to-door component necessarily diminished during the health crisis, due to social distancing). There is a “lucrative fault” effect here: despite various fines, convictions and bad publicity, the use of this type of practice persists because it remains profitable.

To conclude on this point, let’s emphasize that this sector, even if it features prominently, is not the most litigious. In fact, the supply of electricity does not lend itself to a high rate of disputes. It’s easy to understand why there are so many disputes concerning work on the home (disagreement over the quality of the work), relations between landlords and tenants (the famous security deposit and the inventory of fixtures at the end of the lease) or insurance (when a claim is made). For a whole host of reasons well understood by economic science (moral hazard, uncertainty that cannot be reduced by experience, incomplete contracts, etc.), these services will always be highly conflictual. There’s nothing like this in the electricity sector, which is a very “quiet father” business: we connect, we count, we bill.

The fact is that the opening up of the market has created a conflictuality and toxicity that didn’t exist before, and that had no reason to exist.

In times of wholesale market crisis: the “TRV replica” breaks down

The second configuration refers to the period of soaring wholesale market prices that Europe has been experiencing since winter 2021-2022. The virtual nature of competition is expressed in a different way.

We might have expected suppliers who do not produce electricity to protect themselves against the variability of the wholesale market (generally by hedging – see box), and for the regulator to be vigilant on this point.

Unfortunately, the various reactions of alternative suppliers to the surge in wholesale prices at the end of 2021 have shown that this was not the case: sudden closure at the beginning of October 2021 of all new subscriptions; and/or a sudden increase in their prices (often by 20 or 30%); and/or a switch from offers indexed on the TRV to indexation on the wholesale market; or even exit from the electricity market or bankruptcy.

All these reactions add up to the majority of alternative suppliers (Total and Engie, the two biggest alternatives, being the exception, however), and probably denote more or less imperfect hedging in most cases. In short, not producing anything and not being hedged reflects a very virtual and speculative positioning. It’s hard to believe that no prudential principle has been foreseen or concretely applied by the regulator.

Lack of market coverage: a regulatory loophole

Electricity is a “commodity” sector, now backed by a wholesale market like gas, oil or grain. Producing suppliers may not be very dependent on this market, as they can rely on their own supplies. But suppliers who produce nothing are highly exposed to this market. As always with commodities, wholesale markets are cyclical and highly volatile. This volatility is even specifically high for gas and electricity. In the case of electricity, this is due in particular to the fact that electricity cannot be stored in real time (hour by hour), which sometimes results in very surprising prices.

In this context, suppliers must normally protect themselves against volatility by buying in advance the volumes they believe they will have to offer in the future. They will therefore buy one, sometimes two, years in advance on dedicated futures markets. If they don’t, they run the risk of experiencing an explosive rise in their supply costs. This is particularly problematic if they have sold fixed-price offers or offers indexed to the regulated tariff (which is often the case).

There are no rules: the Ministry of Ecology, which awards operating licenses to energy suppliers, requires no minimum coverage to operate.

At the start of the energy crisis, many suppliers stopped taking on new customers for several months (a rare occurrence in economic history), while others implemented very sharp price rises, probably due to poor market coverage.

Conclusion

A market characterized by the desire to eradicate barriers to entry

As this is a sector that corresponds fairly closely to the characteristics of a natural monopoly, opening up electricity supply to competition required a very active policy of eradicating barriers to entry.

Today, any supplier can purchase EDF’s nuclear output for a guaranteed price that replicates the regulated sales tariff (minus 5%); any supplier can access guarantees of origin to offer green electricity; and finally, in terms of market coverage, no prudential guarantees are required.

In fact, the absence of barriers ends up being quite simply counterproductive, as it encourages a form of competition that is both highly artificial and toxic. Ultimately, removing a barrier to entry is a testament to talent, to an idea, to an innovation (technological or otherwise) that genuinely changes something in the market.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that EDF should receive a bonus for some kind of superiority, which is highly debatable; it just means that we shouldn’t want to maintain competition simply because the objective is… to keep the principle of competition alive. Constantly eradicating barriers to prevent the house of cards from collapsing is tantamount to perpetuating a house of cards with little added value and many perverse effects.

Let’s just say that we’re constantly reproducing the first “Far-West” years of a sector that never consolidates, and manifests itself in the endless pursuit of 40 suppliers for private customers (maybe 20 at the end of a wholesale market crisis, but it doesn’t matter) “all on the same line” with no differentiation, and who can therefore only rely on toxic or risky practices to break through.

We need to understand in more detail why the telecoms sector has generally succeeded (at least from a consumer point of view) where the electricity sector has failed. There are 4 dominant operators who have gradually (but right from the start, in fact) invested in the network, and the multitude of virtual operators who entered the market in the 2000s is in decline (their market share was 8.9% in 2021, according to the regulator’s market observatory). These new entrants have really shaken up the incumbent’s pricing model. It is competition that has given rise to innovations such as triple play and the box. What’s more, market regulation has probably been more pragmatic than in the energy sector. In the mobile sector, for example, it was enough to allocate one (and only one) additional license to an operator to create competition, but at the cost of network investment.

Regulation marked by a desire to keep the market “contestable

According to economic theory, a market is contestable if it can be entered at any time without additional cost. In the energy sector, this notion has been applied very extensively, considering that all suppliers should be competitive relative to the incumbent. Regulation of the sector is guided above all by this objective.

In the energy sector, the Community framework, and the Commission’s activism, means that we have to deploy an armada of pro-opening measures to keep the market “contestable”, which amounts to eradicating all barriers, and without asking for any particular concrete commitment. Regulators and the French government probably also missed the boat when they gave little thought to the obligation for alternative energies to develop production (which the Nome Law vaguely outlined).

The only result was to create a multitude of “want to be mini amazon of electricity” whose ultimate goal was to be bought out by Total (Lampiris, Direct Energie) or an investment fund (Powéo).

This situation reflects institutions’ lack of interest in the retail market.

This analysis is arguable. However, a striking feature of the bias of European and French energy institutions is their lack of interest in the retail market (which is said to be less noble than major wholesale markets or major energy balances). Even though the great historical liberalization of electricity is above all an opening up of the retail market, these institutions are interested in the upstream repercussions of the sector, but take little interest in the structuring of the downstream. In fact, to repeat the introductory statement, they assume that if 1°) “a private individual can speak to a customer service other than that of EDF”, and 2°) more and more of them are doing so, then the objective of opening up the retail market has been achieved.

It’s time they took a more serious and less dogmatic look at the issue.

Appendix – Explanations and definitions of the electrical system

The following descriptive elements will help you better understand the rest of the presentation and master the necessary vocabulary.

A. The physical circuit of electricity

The power system is made up of a set of generation plants and a Europe-wide interconnected grid, which automatically delivers electricity to consumers in real time. The main players in the physical dimension of the power system are producers and grid operators.

A.1 French electricity generation totaled 523 TWh in 2021

It is dominated by nuclear power plants (69% of the total). Then come hydroelectric power plants (12%), other renewable energies (12% – wind, photovoltaic, renewable thermal) and fossil-fired power plants (7%, mainly gas). 15 .

In 2019, EDF accounted for nearly 85% of French generation (around 420 TWh), followed by Engie (4% of generation, or 25.5 TWh). 16 then the two main fossil-fired electricity producers Gazel Energie (less than 1%, or 5 TWh) and Total. Finally, the bulk of the remaining production (55 TWh) was provided by more than 350,000 renewable energy production sites. 17 .

French electricity production supplies not only the national territory, but also neighboring countries via exports made possible by interconnections between national transmission networks. Conversely, when French production is insufficient, producers in neighboring countries can supply national consumption. Overall, the balance of trade is positive for France (which will have exported 87 TWh and imported 44 TWh in 2021).

A.2 Electricity grids transport electricity from generation sites to end consumers (households, businesses, public administrations, etc.).

The electricity transmission network (High and Extra High Voltage lines) carries electricity from production plants to major consumption areas. The French network is linked to the transmission networks of other European countries via interconnections, enabling French production to be exported when it exceeds national demand (and when other countries need it), and vice versa.

At the local level, distribution networks (medium and low-voltage lines) take over from the transmission network to supply every district, every street, every building and, ultimately, every consumer. 18 .

A.3 Grid operators: key players in the power system

RTE is the owner of the French electricity transmission network. In 2021, it will be operating a network with 105,970 km of lines, almost 5,000 distribution and transformer substations, and some 50 interconnections with other European countries. In addition to maintaining and developing this network, RTE is responsible for balancing the power system and ensuring security of supply. At any given moment, the total production injected into the network by the various producers must be equal to the consumption drawn by network users. In the event of even the slightest imbalance, blackout occurs.

Local authorities own the electricity distribution network on their territory. They have delegated management to ENEDIS for 95% of France. The remaining 5% is managed by some 150 local distribution companies(ELD). In addition to operating and maintaining the existing network, the distribution network operator connects new consumers, carries out troubleshooting and reads electricity meters. In short, he handles all aspects of customer relations relating to the physical distribution of electricity.

B. The electricity financial circuit

B.1 The retail electricity market: all contracts concluded between end consumers (households, businesses, public authorities, etc.) and their electricity supplier

Consumers don’t buy their electricity directly from producers, but from intermediaries called electricity suppliers. Today, there are around 80 of these in France, half of them for individual consumers. Their role is to propose electricity sales contracts to consumers: to design an offer, canvass customers, conclude contracts, invoice customers and buy electricity on the wholesale market (see below).

A distinction is made between incumbent suppliers, who existed before competition was opened up (EDF and some of the ELDs), and alternative suppliers, i.e. companies set up after competition was opened up.

All alternative suppliers are able to offer consumers market offers (the various existing offers are detailed in sections 2 and 3). In addition, incumbent suppliers can offer regulated sales tariffs to individual customers and micro-businesses. These tariffs, which were the only offer available before the market opened up, are set by the Commission de Régulation de l’Énergie and validated by the government.

B.2 Suppliers purchase electricity on the wholesale market

Once suppliers have customers, they need to source electricity. Indeed, when a supplier is also a producer, like EDF, it can sell its production directly to its customers. But this is not the case for the vast majority of alternative suppliers, who must therefore buy electricity from producers on the wholesale electricity market.

The wholesale market

This is the exchange for electricity professionals. These include electricity producers and suppliers in particular, but also many other players such as network operators, balance responsible parties, large industrial customers and even traders with no real link to production or supply.

Wholesale prices cover different types of price, depending on the time between purchase and delivery of the electricity. It is possible to buy electricity for the next day (spot price) or for delivery over the longer term, between 1 month and 3 years after purchase (forward price).

Source For more information on the wholesale market and price formation, see our fact sheet on the electricity sector.

B.3 Suppliers can “hedge” on the wholesale market

On the one hand, suppliers enter into contracts with consumers in which they undertake to supply electricity for a price that is fixed in advance and can change in moderate proportions. On the other, they buy on the wholesale market, which is highly volatile (as demonstrated by prices in winter 2021-2022).

A prudent policy for a supplier is therefore to hedge, i.e. to buy forward electricity at a time when prices are low, in order to protect against too sharp an increase in prices.

C. No correspondence between the physical and financial circuits of electricity

It is important to understand that electricity purchases do not correspond to a traceable physical delivery. The transmission and distribution networks distribute all production to all consumers according to physical laws, without it being possible to direct any particular production to any particular consumer: buy-sell contracts have no influence on these physical laws. If I’m a supplier and I buy electricity from producer X to supply my customers located in Brittany, this in no way means that the electricity produced by X will supply my customers. It only means that I have purchased a volume of electricity injected into the grid equal to that which my customers have withdrawn.

- The transmission and distribution networks remain public monopolies. Electricity generation is still largely dominated by the historic monopoly EDF. With the opening up to competition, however, this company has been privatized, some of its hydroelectric power stations have been sold to the Compagnie Nationale du Rhône (now owned by ENGIE), and new producers have emerged, particularly in the field of renewable energies. For more information, see our fact sheet on the electricity sector. ↩︎

- EDF and Engie are the two suppliers who also have a significant production activity. ↩︎

- A company in a monopoly situation may seek to increase its margin excessively at the expense of consumers. ↩︎

- This was indeed the case initially, but recent developments have sought to integrate market prices more and more into the TRVs. See sheet on the electricity sector ↩︎

- These are Ipango and C discount ↩︎

- Alternative suppliers are those that emerged after the market was opened up to competition. Those who existed before are the incumbent suppliers (mainly EDF and ELD _ local distribution companies). ↩︎

- They can also expect a bit of information to help them control their consumption, which can be provided by the supplier or by another player (the distributor, a specialized player). ↩︎

- There would be no point (technical, economic or ecological) in duplicating the networks. ↩︎

- CRE’s 2018-2019 report on the retail electricity and gas market (p8) ↩︎

- Opinion column by Antoine Nogier, President of Sun’R, in Le Echos, 10/04/2019 : “Green electricity: guarantees of origin that guarantee nothing”. ↩︎

- An electro-intensive industrial company agrees to stand down (stop consuming electricity) at a time of peak demand, in exchange for an attractive financial reward from the electricity system. ↩︎

- See explanations on dynamic pricing offers on the Energy Ombudsman website. ↩︎

- See the article What’s behind $15,000 electricity bills in Texas? The Conversation, February 2021 ↩︎

- This is Article 11 of Directive (EU) 2019/944 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and amending Directive 2012/27/EU. ↩︎

- Source – RTE 2021 balance sheet ↩︎

- Second-largest hydroelectric park, leading solar and wind power producer, some fossil-fired power plants. ↩︎

- Source: L’organisation des marchés de l’électricité, Cour des comptes report, 2022 ↩︎

- It should be noted that some large industrial consumers (known as “electro-intensive”) are directly connected to the transmission network without passing through the distribution network. ↩︎