This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) is a multilateral agreement signed in 1994, initially aimed at securing Western Europe’s energy supplies in the countries of the former Soviet bloc, by protecting foreign investors from possible negative economic impacts resulting from legislative changes decided by the States subsequent to the investments made. To this end, the treaty gives investors the possibility of suing these states in private arbitration tribunals and claiming substantial financial compensation.

In this article, we explain what the ECT is and show how it is an obstacle to the fight against climate change. It locks in investment in fossil fuels at a level that is incompatible with compliance with the Paris climate agreement. 1 Generally speaking, the ECT calls into question the sovereignty of States over their energy policies.

What is the Energy Charter Treaty?

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) aims to promote cooperation and security in the field of energy. It covers all economic activities in the sector except those relating to the reduction of energy demand. 2 These include the exploitation, extraction, refining, production, storage, transport, transmission, distribution, exchange, marketing and sale of energy materials or products. The ECT does not distinguish between polluting activities and decarbonized energies.

This legally binding treaty, which came into force in 1998, has 53 contracting parties as of mid-2022, including the European Union, the EU member states (except Italy, which withdrew in 2016) and the United States. 3 ), other European countries (United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway 4 ), Central Asian countries, Turkey and Japan.

The Treaty’s objectives: four main areas of action

The objectives set out on the treaty website cover four main areas:

- foreign investment protection and protection against major non-commercial risks ;

- non-discriminatory conditions for trade in energy materials, products and equipment, as well as provisions to ensure the reliable transport of energy by pipelines, networks and other means ;

- the settlement of disputes between participating States, and between investors and States ;

- the promotion of energy efficiency and efforts to minimize the environmental impact of energy production and use. However, these provisions are not binding, and foreign investments aimed at reducing energy demand are not protected by the ECT.

Using private arbitration to protect foreign investments

The best-known and most problematic aspect of this treaty concerns the use of private arbitration to protect investors residing in the territory of one of the contracting states and having invested in the energy system of another contracting party. Indeed, the ECT gives these investors the possibility of demanding financial compensation from the States, should a change in their energy legislation have a negative impact on the investments made and the benefits they expected to derive from them.

The amounts demanded can run into the hundreds of millions or even billions of euros (and all the more so since, as we shall see, the mere threat of the ECT can induce states to pay). To settle disputes between States and investors, the latter can have recourse to private arbitration tribunals or national courts, both options being provided for by the ECT. 5

What is a private arbitration tribunal?

Arbitration is a private, fee-paying form of justice, responsible for settling disputes submitted to it by the parties in accordance with the principles of law. 6 Broadly speaking, the parties to a dispute agree to have recourse to an arbitrator (or arbitration tribunal) rather than the courts to settle their dispute.

The inclusion of private arbitration tribunals in trade treaties emerged after decolonization, at the request of European-based multinationals. The latter justified the need for neutral arbitrators by their distrust of local courts in settling disputes with nationalist governments, which did not hesitate to expropriate foreign investors in order to implement development policies. Since then, this system has developed considerably, and has become the most common means of resolving international disputes between governments and investors in many industrial sectors, such as energy.

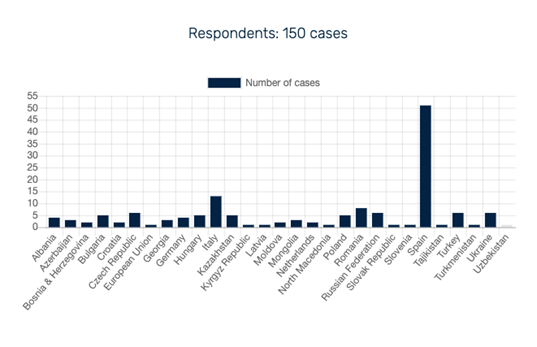

In April 2024, the TCE secretariat claimed to be aware of 150 arbitration cases launched under the TCE. 7

Conditions for withdrawal by a contracting party and the “sunset clause”

The procedures for withdrawing from the ECT, set out in article 47, are relatively straightforward.

The withdrawal of a contracting party takes effect one year after the date of receipt by the Energy Charter Conference of the written notification in which that party has expressed its wish to withdraw from the treaty.

However, simply leaving the ECT is not enough to avoid litigation. In fact, Article 47 includes a provision known as the “sunset clause”, according to which “the provisions of the Treaty shall continue to apply to investments made in the area of a Contracting Party by investors of other Contracting Parties or in the area of other Contracting Parties by investors of that Contracting Party for a period of 20 years after the exit date”.

In other words, the mechanisms for protecting investments made before withdrawal continue to apply for 20 years after leaving the treaty. This is, for example, what happened in 2022 for Italy, whose withdrawal from the ECT took effect on January 1, 2016.

The case of Rockhopper vs Republic of Italy

In December 2015, the Italian parliament approved a moratorium banning all oil and gas projects within twelve nautical miles of the Italian coast. Rockhopper, which had obtained the license for the Ombrina Mare oil platform project (in the Adriatic Sea off the Abruzzo region) in the summer of 2014, decided to file a complaint under the ECT. After several years of proceedings, the company won its case in August 2022: six years after withdrawing from the ECT, the Italian state had to pay Rockhopper a fine of €190 million (plus interest).

Read more :

– Rockhopper press release

– several articles on billateral.org and isdstories websites

Securing Europe’s energy supply, an obsolete raison d’être of the treaty

A treaty to secure supplies for Western Europe

One of the major aims of the ECT was to secure Western Europe’s supply of fossil fuels from the former Soviet bloc republics, by protecting the operations of foreign companies in these countries.

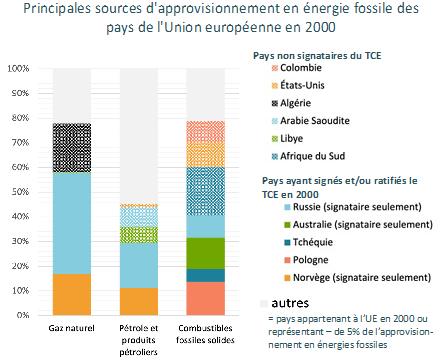

The following graph shows all countries (not members of the EU in 2000) representing more than 5% of EU supply in one of the three main fossil fuel categories at the end of the 1990s (i.e. when the ECT came into force).

Source Eurostat – Imports by partner country of solid fossil fuels; petroleum and petroleum products; natural gas.

As we can see, from the point of view of securing energy supplies, the ECT made sense in the 2000s, since the signatory countries accounted for almost 60% of the EU’s gas supplies, 40% for solid fossil fuels (coal) and 30% for oil and petroleum products.

This is much less true today.

Energy Charter Treaty no longer includes major EU energy suppliers

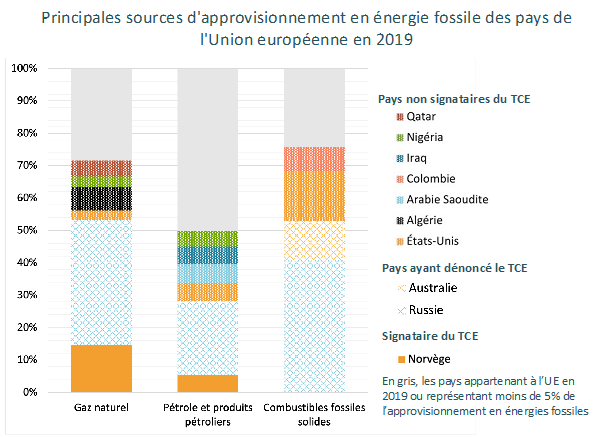

Source Eurostat – Imports by partner country of solid fossil fuels; petroleum and petroleum products; natural gas.

Of the EU’s main sources of fossil fuel supply (outside member countries), only Norway remains a signatory to the ECT. Russia withdrew from the treaty in 2009, definitively in 2018, and Australia in 2021. The only other TCE signatory supplying the EU in any significant way is Kazakhstan (not shown here), which supplied around 4.5% of the EU’s oil and petroleum product imports in 2019. However, these two countries are also signatories to other treaties with the EU that include the energy sector: Norway is a member of EFTA (European Free Trade Association) and Kazakhstan of the Central-Asian Partnership (non-binding treaty).

The energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine in 2022 has further confirmed the futility of the ECT. As the diagram clearly shows, Russia is by far the EU’s biggest supplier of fossil fuels. With Russia’s withdrawal from the TCE, its raison d’être has become obsolete.

The attempt to extend the Energy Charter Treaty to Africa

To address this situation, a strategy to extend the TCE to countries with large fossil fuel reserves was developed from the 2010s onwards. African countries are the priority targets for this extension, which is mainly financed by EU development funds (see box).

Despite the efforts made and the detour of development funding to prepare African countries for accession to the ECT, the latter have not succeeded in adjusting national legislation to enable implementation of the treaty’s provisions, in particular the use of private arbitration tribunals, which is of primary interest to European companies.

Accession to the ECT: is development aid really well spent?

In particular, the technical assistance financed by the EU as part of the implementation of the objectives of access to clean energy for all by 2030 has been partially used to train African experts in TCE. More recently, as part of a project to support the establishment of modern energy governance in West African countries, the EU has been financing since 2019, through the 11th European Development Fund, the hosting by the TCE secretariat of national experts to prepare their countries’ accession to the Energy Charter Treaty. One may legitimately wonder whether European development aid would not be better used to finance energy access projects…

How are investors using the Energy Charter Treaty to bend governments to their will?

Brandishing the threat of compensation claims before private arbitration tribunals

Foreign investors don’t need to wait for a new law to be passed to put pressure on governments for compensation. All they have to do is invoke the Energy Charter Treaty and brandish the threat of a compensation claim before private arbitration tribunals for governments to abdicate. This was, notably, the case in 2017, with the Hulot law on the end of hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation, which was emptied of its substance simply by the threat 8 from the Canadian company Vermillion that the law violated “France’s international commitments as a member of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty”. 9 . This threat was possible even though Canada is not a signatory to the ECT (see box).

Who are the foreign investors affected by the ECT?

These are financial or industrial companies domiciled in one of the contracting (or signatory) countries and having invested in another contracting country. For example, investors from one European country are considered “foreigners” in other EU countries. 10 It is important to note that it is not necessary for the parent company of the company concerned to be domiciled in a contracting country. For example, for the Canadian company Vermillion to benefit from the ECT, all it has to do is domicile one of its subsidiaries in a signatory country.

On the other side of the Rhine, the German government has offered, as part of the agreement on the coal phase-out scheduled for 2038 11 compensation of over 2.6 billion euros to the RWE conglomerate and 1.75 billion euros to LEAG, on condition that the Energy Charter Treaty is not used for recourse to private arbitration tribunals. The German government’s decision was prompted by the country’s ongoing disputes with Sweden’s Vattenfall, which is claiming over €6 billion in compensation for the premature shutdown of a nuclear power plant and the compliance of a coal-fired plant with European environmental standards.

The most frequently invoked treaty in disputes between foreign investors and governments

The ECT is a little-known treaty among political decision-makers, the media, NGOs and the general public, but it is the most frequently invoked treaty in disputes between foreign investors and states. As of June 1, 2022, the Energy Charter Secretariat reported 150 known disputes 12 invoking it. More than two-thirds of these are intra-European disputes linked to the reduction in subsidies for the production of electricity from renewable energy sources. Spain leads the way, with some fifty disputes in progress, representing total compensation claims of over 8 billion euros. Italy and the Czech Republic are the other two countries hardest hit by the ECT. In September 2022, France was sued for the first time: German renewable energy producer Encavis AG is contesting the government’s decision to modify its feed-in tariffs for photovoltaic solar power, a decision justified by the considerable drop in prices in the sector.

The Energy Charter Treaty is an obstacle to the ecological transition

A treaty that protects fossil fuel investments

By protecting foreign investment in fossil fuels, the ECT defends foreign investment in assets with high greenhouse gas emissions (such as coal-fired power plants, refineries, etc.).

Respecting the objective of limiting global warming to well below 2°C adopted by the international community in the Paris climate agreement means ceasing to use some of these assets before they reach the end of their economic life.

The term ” stranded assets” refers to assets that will have to be written down as a result of the necessary changes in legislation to comply with the Paris Agreement.

IPCC Sixth Assessment Report on climate (2022) 13 explicitly cites TCE as a tool used by the owners of these assets to block climate action. Indeed, the TCE protects these fossil assets by preventing their “stranding”.

“Despite improvements in international energy governance, it seems that much of it is still aimed at promoting the continued development of fossil fuels. One aspect of this situation is the development of international legal standards. A large number of bilateral and multilateral agreements, including the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty, include provisions for the use of an investor-state dispute settlement system (ISDS) designed to protect the interests of investors in energy projects from national policies that could lead to the stranding of their assets. Many specialists have indicated that ISDS could be used by fossil fuel companies to block national legislation aimed at phasing out the use of their assets.” 14

The OpenExp think tank has estimated that fossil fuel assets protected in this way will total 870 billion euros by the end of 2019. 15 . This figure could rise to 2,150 billion euros by 2050 if foreign investment in fossil fuels continues to be protected.

The ECT before the European Court of Human Rights

On June 21, 2022, 5 young Europeans took twelve signatory countries of the ECT to the ECHR, arguing that by protecting fossil fuels, the treaty is incompatible with the countries’ climate commitments.

On February 9, 2023, the Court adjourned consideration of the case pending the Grand Chamber’s examination of three other climate-related cases: Verein Klimaseniorinnen Schweiz and others v. Switzerland; Carême v. France; and Duarte Agostinho and others v. Portugal and 32 others. France; and Duarte Agostinho and others v. Portugal and 32 others.

On April 9, 2024, the Grand Chamber of the ECHR handed down its decisions in all three cases, holding the French and Portuguese applicants inadmissible, but making an interesting ruling in the Swiss case:

The ECHR affirms that to protect their citizens’ “right to life”, states have an obligation to act against global warming.

While this is a landmark case, it in no way guarantees the outcome of the proceedings brought against the ECT member states, which could drag on for years yet.

Source The exitect.org website, which presents the legal case The ECHR press release on the Grand Chamber judgment in the case of Verein KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz and others v. Switzerland

A treaty that increases the cost of the energy transition

The TCE’s promoters, led by the secretariat that manages the treaty, argue that it is an indispensable tool for speeding up the energy transition, citing the high number of disputes linked to the reduction in subsidies for the production of electricity from renewable energy sources.

Good governance of the energy transition means regularly adjusting subsidies for investment in renewable energies to market realities. This is what has happened in several EU countries with the spectacular fall in the cost of photovoltaic (-85%) and wind power (-55%) installations between 2010 and 2019. 16 .

However, these adjustments can cost taxpayers billions of euros in legal proceedings and compensation in countries that have signed the ECT. Reductions in subsidies for renewable energies have been applied without distinction to domestic and foreign investors, except in Portugal where feed-in tariffs for wind power, which mainly involves foreign investors, have been extended until 2036, while subsidies for solar installations, which mainly involves domestic investors, have been adjusted to market reality.

Admittedly, the Portuguese decision avoided recourse to private arbitration tribunals, as provided for in the ECT, for the settlement of disputes between investors and States, but this decision, which is the result of secret negotiations 17 with foreign investors, including Chinese, who bought up some of the wind farms at the time of the financial crisis, has increased the cost of the energy transition for Portuguese taxpayers. Indeed, Portugal is the EU country with the highest level of subsidies for wind power generation. Despite this, supporters of the Energy Charter Treaty consider Portugal’s strategy for avoiding litigation to be good practice.

The Energy Charter Treaty weakens states and threatens democracies

An obstacle to national energy sovereignty

The ECT contains no explicit provisions to protect states’ right to legislate. As a result, contracting parties lose sovereignty over their energy and climate policies to foreign investors.

This is borne out by well-known disputes such as the one between Nord Stream and the European Union concerning the implementation of the EU directive on common rules for the internal market in natural gas. Based in Switzerland and owned by Russian gas giant Gazprom, Nord Stream AG was set up to build the NordStream2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea. The company is contesting the extension of unbundling rules in the gas sector to non-EU countries, on the basis of EC Treaty provisions, and is seeking compensation from the EU (for an undisclosed sum).

The Haut conseil pour le climat (HCC ), an independent body set up in 2018 to shed light on the French government’s climate policy, expressed very clearly, in its opinion on the modernization of the TCE, the loss of sovereignty of the signatory states in terms of energy and climate policies.

“The ECT includes a dispute settlement mechanism enabling investors to resort to international arbitration against signatory states, particularly in the event of unilateral modification of their legislative or regulatory frameworks in the energy sector. This mechanism has generated an increased risk of loss of sovereignty for signatory states in the development or implementation of their energy and climate policies, and led to a proliferation of litigation and arbitration awards in conflict with the decisions of national and European courts.”

An obstacle to climate justice and a cost for the taxpayer

The ECT is also a threat to democracies, as it prevents governments from enforcing legal rulings issued by national courts and resulting from citizen action in climate litigation, as is the case in Italy and the Netherlands. In both cases, the legal battle won by citizens – to halt fossil fuel exploration in the Mediterranean in the case of Italy (see box in part 1.C) and to shut down coal-fired power plants before the end of their lifespan in the Netherlands – has been a major success. 18 This could cost taxpayers exorbitant sums to compensate foreign investors.

These two cases are very likely to be the first of many to come, if governments are serious about implementing the Paris agreements.

“Over the period 2013-2019, the average annual number of transactions (contracts in the energy sector with foreign investors) protected by the ECT is estimated at 407 transactions, 54% of which are fossil fuel-related.” 19“Ending all fossil fuel agreements protected by the ECT, since its entry into force, would potentially cost taxpayers an additional 523.5 billion euros on average, including 503 billion euros in arbitration awards, should investors win, and 20.5 billion euros in legal and arbitration fees. Continuing the private arbitration mechanism under the ECT regime until 2050 will increase this cost to 1,300 billion euros, 42% of which will be paid by European taxpayers.” (Source: OpenExp, 2020)

A privileged instrument at the expense of European law

More than two-thirds of foreign investment in the energy sector within the EU is intra-European. They are therefore protected by the rules of the common market, as set out in the Lisbon Treaty. However, the use of private arbitration tribunals to settle disputes between investors and states, as provided for in the ECT, is more advantageous than European law for European investors. This explains the large number of intra-European disputes brought under the ECT.

In the “Komstroy” judgment of September 2, 2021 20 the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that the EC Treaty’s arbitration clause (art. 26) was not applicable to disputes between a Member State and an investor from another Member State concerning an investment made by the latter in the first Member State.

However, although this ruling is good news, its application to existing and future disputes is subject to considerable legal uncertainty. Indeed, as the European Commission points out in an October 2022 communication, “in their constant and almost unanimous decision-making practice, arbitration tribunals continue to consider that the ECT arbitration clause applies intra-EU.” 21

What are the ways out of an anti-climatic and anti-democratic treaty?

The withdrawal of the EU and its member states from the treaty

The lack of progress made during the “modernization” process (see below) has encouraged several EU countries to seriously consider this option, and, for some, to begin implementing it through unilateral withdrawal.

More and more unilateral withdrawals

In a letter dated December 2020, Bruno Le Maire and three other ministers asked the European Commission, on behalf of the French government, to analyze the legal implications of a collective exit by EU countries from the TCE. This letter was France’s response to the strong mobilization in favor of a collective exit from the TCE. 23

France’s request was followed in 2021 by those of Spain, which threatened to withdraw unilaterally from the ECT if the option of collective withdrawal was not considered by the European Commission, then Poland, and Greece.

In October 2022, Poland passes a law terminating the Energy Charter Treaty. In the weeks that followed, Spain, the Netherlands, France, Slovenia, Germany and Luxembourg announced their withdrawal from the ECT. In 2023, it’s Denmark’s turn, followed by Ireland and Portugal.

Together with Italy, which left the ECT in 2016, these countries represent 75% of the European Union’s population.

Outside the EU, Australia in November 2021 and the UK in February 2024 have also announced their withdrawal from the Energy Charter Treaty.

A coordinated exit from the EU

Faced with this pressure from member states, the European Union took up the issue. In June 2022, the Parliament “calls on the Commission and the Member States to start preparing their coordinated exit from the TCE”. 24 . On July 7, 2023, the Commission presented a proposal for a coordinated EU exit from the TEC.

The outdated Energy Charter Treaty is not aligned with our European climate law and our commitments under the Paris Agreement. It is time for Europe to withdraw from this treaty.

The text was the subject of debate, with some countries, such as Slovakia and Hungary, wishing to remain part of a modernized TCE. In the end, a compromise was adopted by the Council in March 2024: on the one hand, the withdrawal of the EU and of those member countries that so wished 25 and, on the other, amendments to be adopted by the Energy Charter Conference, as part of the treaty modernization process, for the remaining member states. In particular, the text 26 which should be adopted by Parliament on April 22, 2024, seeks to limit the ECT’s protections on fossil fuel investments, and to exclude from the treaty “letter-box companies”, subsidiaries set up in an ECT member country solely to benefit from the treaty’s clauses.

The importance of neutralizing the “sunset clause”

In its opinion on the modernization of the ECT, the HCC points out that “to be compatible with the decarbonization timetables brought about by the Paris Agreement and to restore the sovereignty of the energy and climate policies of the signatory parties concerned, a coordinated withdrawal must be coupled with a protective neutralization of investments covered by the ECT, known as the ‘sunset clause””.

Indeed, as explained in section 1.C, the “sunset clause” enables investments made before the withdrawal of a contracting party to be protected under the ECT for 20 years following the effective withdrawal. The “neutralization” of this clause is therefore essential to ensure that investors who feel aggrieved by a State’s climate and energy policies have no recourse to private arbitration.

This is why the Commission is planning, in conjunction with the above-mentioned positions on withdrawing from and modernizing the ECT, to adopt a treaty interpretation agreement:

“In particular, this agreement should confirm that a clause such as Article 26 TEC could not in the past, cannot now and will not in the future serve as a legal basis for arbitration proceedings brought by an investor from one Member State concerning investments in another Member State”.

As the majority of procedures are intra-European, the adoption of such an agreement would sound the death knell of the treaty.

Treaty modernization: an insufficient response to energy and climate challenges

Some states (Switzerland, some EU member states) support modernizing the ECT rather than abandoning it, despite the fact that the entry into force of the modernized ECT – whose amendments must be adopted unanimously and then ratified by at least three-quarters of the signatory parties – could take years.

Opened in 2017, the so-called “modernization” process of the TCE has been the subject of fifteen rounds of negotiations. The most recent concluded with the adoption on June 24, 2022 of an agreement in principle setting out the main principles of the treaty changes.

The revised version of the ECT and its annexes was then transmitted by the Energy Charter Secretariat to the contracting parties, but was not made public. The European Commission published its proposed amendments on October 6, 2022 22 . The treaty’s modernization should have been ratified at the 33rd meeting of the Energy Charter Conference, held on November 22, 2022. However, blocking by several European countries caused the vote to be postponed – initially scheduled for April 2023, then postponed again until the course of 2024.

The main advances on fossil fuels that emerge from the agreement in principle and the amendments proposed by the European Union are as follows:

- The introduction of a flexibility mechanism enabling contracting parties who so wish to end the protection of fossil fuel investments on their territory. Existing investments would be protected for ten years following the entry into force of the revised ECT (and until December 31, 2040 at the latest).

- New provisions that reaffirm the “right to regulate” of States, i.e. to take measures to achieve “legitimate political objectives”, notably in the fight against climate change.

- The introduction of a new article stipulating that dispute settlement provisions (between contracting parties; and between an investor and a contracting party) do not apply to parties that are members of the same regional economic integration organization. As the European Union is the only such organization, this new article would confirm the position of the EU Court of Justice that arbitration is not available for intra-European investments (see section 5.C).

While these advances are interesting, they remain largely insufficient to meet the energy and climate ambitions of France and the European Union in general. Thus, in its opinion on the modernization of the ECT, the French High Council for the Climate

concludes that the TCE, even in its modernized form, is not compatible with the pace of decarbonization of the energy sector and the intensity of emission reduction efforts required for the sector by 2030, as reiterated by the IEA and assessed by the IPCC.

- Following COP21 in 2015, the signatory states of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change set out in the Paris Agreement the goal of limiting “the rise in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels”. ↩︎

- In fact, the ECT is the only international treaty to include specific provisions on energy efficiency. However, investments in this field are not protected. ↩︎

- Italy notified its decision to leave the ECT on December 31, 2014, for an effective exit on January 1, 2016. ↩︎

- Norway is a signatory to the ECT but has not ratified it. ↩︎

- The list of arbitrations can be consulted on the Energy Charter Secretariat website. ↩︎

- Find out more on Vie publique.fr ↩︎

- Since the parties to an investment arbitration are not required to notify the secretariat of the existence or content of their dispute (art. 26 of the ECT), certain awards (and even the existence of certain proceedings) remain confidential. ↩︎

- Law n° 2017-1839 of December 30, 2017 putting an end to the exploration as well as the exploitation of hydrocarbons and bearing various provisions relating to energy and the environment. To find out more, see the article ” Comment les lobbies ont détricoté la loi Hulot “, Les Amis la Terre France etl’ Observatoire des multinationales, 2018. ↩︎

- Letter to the Conseil d’État from the law firm Piwnica & Molinié, on behalf of Vermillion on the subject of ” Observations on the draft law on the prohibition of the exploitation of hydrocarbons “. ↩︎

- However, this provision has been challenged by the European Court of Justice (see section 5.C) and is likely to change if the current negotiations on the Energy Charter Treaty are successful (see section 6.B) or if the EU Member States reach an agreement on the matter, as recommended by the Commission (see section 6.A). ↩︎

- See Öffentlich-rechtlicher Vertrag zur Reduzierung und Beendigung der Braunkohleverstromung in Deutschland. This agreement provides for a coal phase-out by 2038, and if possible by 2035. A study published by the German think tank OKO Institut showed that the compensation proposed by the German government was too high and unjustified in view of the investment made. ↩︎

- It is quite possible that the number of cases will be higher, as investors and governments are under no obligation to publicize ongoing litigation. ↩︎

- Established in 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an intergovernmental organization comprising 195 countries. Its mission is to provide policy-makers with an assessment of scientific knowledge on climate change, its impacts (environmental, economic and social) and strategies for dealing with them. ↩︎

- IPCC, “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report”, 2022, chapter 14, p.81.See also chapter 15 p.66. ↩︎

- Modernisation of the Energy Charter Treaty: A global tragedy at a high cost for taxpayers, OpenExp, 2020. ↩︎

- Source: IPCC. (2022). ” Climate Change 2022: Mitigating climate change. Contribution dgroupe de travail III au sixième rapport d’évaluation “, summary for decision-makers, section B4.1. ↩︎

- “ERSE admite “sobrecompensação” aos produtores de eletricidade”, Diario de Noticias, 2018. ↩︎

- After being condemned for failing to meet its climate commitments following the“Urgenda affair “, the Dutch state has decided to phase out coal by 2030. In January 2021, the German conglomerate RWE decided to initiate arbitration proceedings against the Netherlands under the ECT. ↩︎

- Source: ORBIS cross-border investment database. ↩︎

- In the Achmea ruling of March 6, 2018, the CJEU had already concluded that investor-state arbitration clauses in international agreements between EU member states are contrary to the EU treaties and therefore cannot be applied. ↩︎

- Source: European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council and the Member States concerning an agreement between the Member States, the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community on the interpretation of the Energy Charter Treaty, COM (2022) 523, October 5, 2022. You will also find in this communication more details on the legal arguments and practices used by arbitration tribunals to disregard the CJEU ruling. ↩︎

- European Commission, Proposal for a Council Decision on the position to be taken on behalf of the European Union at the 33rd meeting of the Energy Charter Conference, October 6, 2022. ↩︎

- See www.endfossilprotection.org for all the mobilizations for the collective withdrawal of EU countries from the TCE. ↩︎

- European Parliament resolution of June 23, 2022 on the future of the Union’s international investment policy ↩︎

- Proposal for a Council Decision on the withdrawal of the Union from the Energy Charter Treaty – 2023/0273(NLE) ↩︎

- Proposal for a Council Decision on the position to be taken, on behalf of the European Union, at the meeting of the Energy Charter Conference – COM(2024) 104 ↩︎