This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

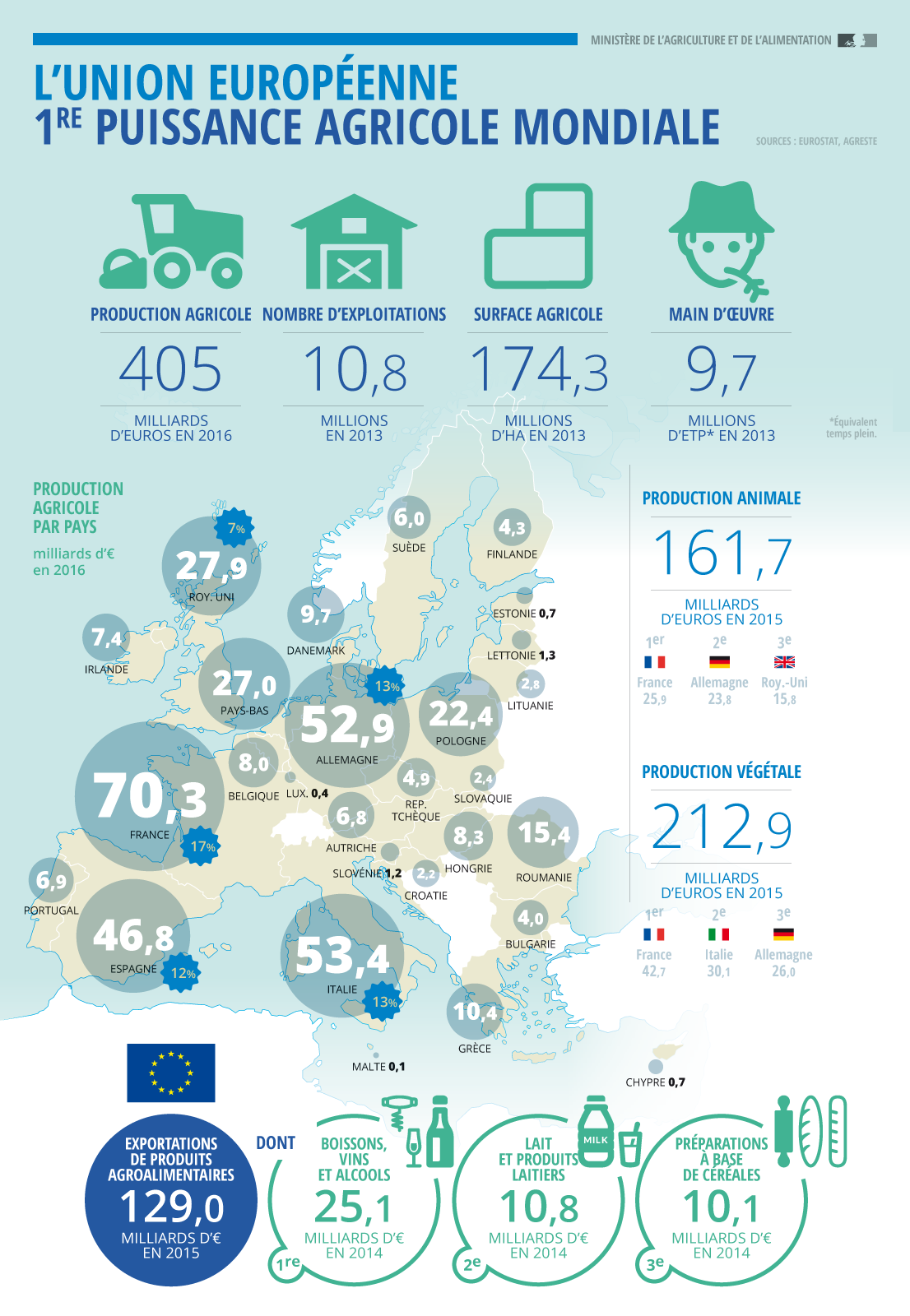

Established in the early 1960s, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is a major policy of the European Union. While it has enabled Europe to become the world’s leading agricultural power and to maintain farmers’ incomes, the numerous attempts at “greening” have not led to a reduction in the environmental impact of agriculture. What’s more, despite providing essential support for farmers’ incomes, the CAP raises a number of questions of social justice, given the poor distribution of aid. The current reform does not seem ambitious enough to reverse these trends.

The initial objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy have been achieved

Provided for in the Treaty of Rome of March 25 1957, the CAP did not come into force until 1962. In a post-war Europe, one of the CAP’s key objectives was to ensure the continent’s self-sufficiency in food. The second priority was to ensure a decent income for farmers, and to bring their standard of living closer to that of industrial workers.

These objectives are clearly set out in Article 39 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Lisbon Treaty). The CAP must :

- increase agricultural productivity by developing technical progress and ensuring optimum use of production factors, particularly labor;

- ensure a fair standard of living for the farming population;

- stabilize markets;

- guarantee security of supply;

- ensure reasonable prices for consumers.

The Union’s liberal approach was to include agricultural products in the free movement of goods, while maintaining public intervention in the agricultural sector. National intervention mechanisms incompatible with the common market had to be eliminated and transposed to the Community level: this was the fundamental reason for the birth of the CAP. Subsequently, European public authorities have always sought to regulate agricultural markets and support producers’ incomes.

At the inception of the CAP, Europe experienced major price fluctuations due to variations in production volumes resulting from both climatic and geographical conditions. The CAP sought to limit these fluctuations by providing income security through substantial subsidies, and by reducing the impact of climatic fluctuations by encouraging farming that relied on more inputs, such as fertilizers and pesticides. The arrival of new machinery has also helped to reduce the variations due to geographical conditions.

Today, we can see that the original objectives have been achieved, even if this has meant a high concentration of farms and numerous negative consequences for the environment.

The first 2 priority objectives set out in 1962 have been achieved, as have the others, even if some still have their doubts.

The European Union has become the world’s leading agricultural power. The Union’s exports represented 129 billion Euros in 2015 (raw and processed agricultural products). Europe has become a major exporter in many sectors, particularly wines, dairy products and cereals.

With regard to the question of farmers’ incomes, it should first be pointed out that comparisons to the nearest euro with the incomes of salaried workers are not relevant, for a number of reasons (an average in agriculture is highly misleading, as the diversity of incomes is far greater than in other professions; farmers’ incomes do not include paid vacations; many farmers live on their farms: their rent or loan repayments can therefore be deducted before income is paid, etc.). The information provided below should therefore be treated with caution, and only as an order of magnitude.

Since the 1990s, the incomes of French farmers have come closer to the average incomes of intermediate professions. 1 . In 1989, the net income of a farmer was 172,000 F per year, equivalent to that of intermediate professions.

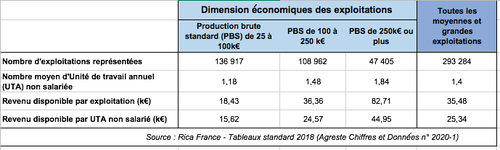

In 2018, according to the Farm Accountancy Data Network (RICA), the average disposable income of farms amounted to around €25,300 per “unsalaried annual work unit” (UTA – i.e. per farm operator) 2 . By way of comparison, in 2016 in France, the average net salary of blue-collar workers was around €20,200 per year, and that of intermediate professions €26,900 (source: Insee).

However, this average figure conceals major disparities, as can be seen from the following table, which details income according to the size of the farms included in the FADN survey, differentiated by farm type. Thus, for medium-sized farms (GDP of €25 to €100k), which represent almost half of the farms included in the FADN survey, income per non-salaried AWU is less than €16,000 per year. Conversely, it reaches €45,000 for the largest farms.

If farmers’ incomes have risen over the years, it’s mainly thanks to CAP subsidies. Advantage, but also risk: farmers’ incomes are now largely dependent on CAP subsidies. In 2018, CAP subsidies accounted for an average of 47% of their income. It’s easy to see why farmers are so worried about every proposed CAP reform!

A CAP that seeks to become greener over time, but with little success

Between 1962 and 1992, CAP subsidies were based on indirect production aids . A system of guaranteed purchase prices was introduced in 4 sectors: cereals, milk, meat and sugar. This system did not encourage producers and processors to seek remunerative outlets. On the other hand, it was highly effective in increasing production volumes and achieving or even surpassing self-sufficiency. The production surplus was such that in the 1980s/90s, the European Union was bursting at the seams with stocks of butter, milk powder (with over 1MT of powder or butter) or cereals. All these surpluses had to be exported with subsidies (export refunds). By the 1980s, CAP budgetary expenditure was such that it accounted for almost the entire Community budget, limiting the development of other common policies, such as regional policy, whose needs increased with the entry of Greece in 1981, followed by Spain and Portugal in 1986.

In addition to the negative impact on the Community budget, these subsidized stocks and exports have had a negative impact on the development of African agriculture. This system of subsidies has also contributed to environmental degradation, as farmers have sought to intensify production by using fertilizers and pesticides, and by developing very large livestock production units, which are the source of pollution (e.g. slurry, which pollutes rivers and coastlines) and poor animal husbandry (poor animal welfare, massive use of antibiotics, etc.).

In 1992, the Mac Sharry reform reform (named after the European Commissioner for Agriculture) put an end to this system of indirect aid with guaranteed prices. The reform introduced direct payments to producers, proportional to farm size. But the distribution of these direct aids was conditional on the respect of set-aside, which was necessary both to cope with the overproduction then affecting the Community and to reduce the environmental impact. Rotating set-aside was intended to reduce pressure on the soil and replenish organic matter. In response to pressure from governments, set-aside was often limited to the least productive areas, with little environmental impact.

A new reform took place in 1999 as part of Agenda 2000. This reform proposed a reduction in the remaining guaranteed prices, to bring them closer to world prices and thus reduce the amount of export refunds. It also encourages greater respect for the environment. Finally, it introduces the notion of the multifunctionality of agriculture, i.e. that this sector not only feeds the population, but also maintains the land. This last point is intended to justify the existence of the CAP in a context of strong questioning.

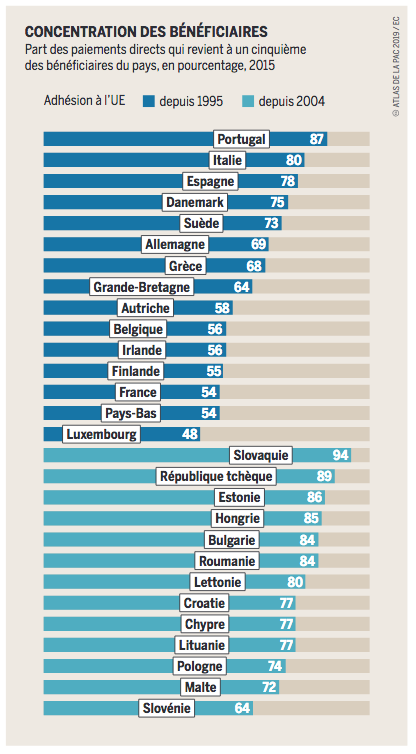

At the beginning of the 2000s, the CAP continued to be strongly criticized by a number of players. One of the main criticisms concerns the fact that this policy essentially benefits large farms, since subsidies are mainly linked to surface area and therefore also to production. The logic of productivism, which is detrimental to the environment and food safety, is thus still in place.

In 2003, a new reform marked the first break with productivism. The aim was to propose a form of agriculture that was more respectful of the environment and food safety, while enabling farmers to benefit from more stable incomes. This reform is highly contested, particularly in France, by the agricultural unions, as it introduces decoupling between production and subsidies. Most direct aids received by farmers are replaced by a single payment per farm, independent of production.

From an environmental point of view, the originality lies in the cross-compliance of aid. This single payment is subject to compliance with 18 standards relating to the environment, food safety and animal welfare. Finally, the reform introduces a reduction in direct payments to large farms, in response to criticism that the CAP is antisocial and benefits the biggest farmers. Payments are capped above a certain threshold.

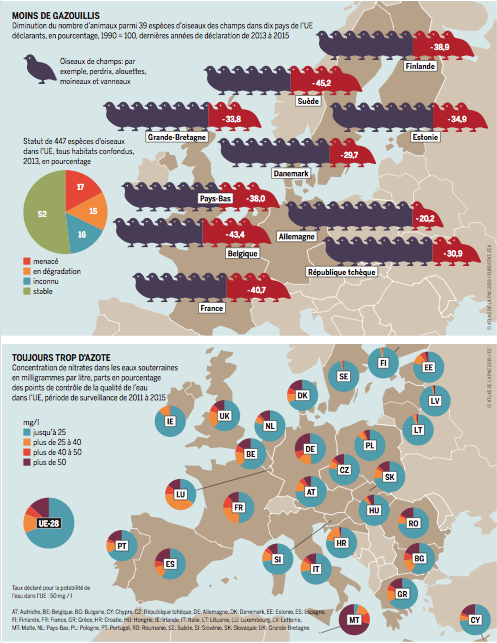

Despite these various reforms and their desire to better integrate environmental considerations into agricultural production, the environmental situation is hardly improving: pesticide use remains high, water and air quality are barely improving, and biodiversity in rural areas continues to deteriorate. A study by the MNHN and the CNRS shows, for example, that farmland bird populations have collapsed by a third in 15 years, at a faster rate than forest or urban bird populations.

What is the current system?

A new CAP that is “fairer, more equitable, greener and more transparent” in the words of the European Commission was implemented on January 1, 2015 and is still in force. The originality of this latest reform is that for the first time since the Lisbon Treaty came into force, the European Parliament is a full co-legislator with the Council.

The 1st pillar of the CAP (economic and income support oriented) is mainly made up of direct payments to farmers, which represented, 72% of the total CAP budget (i.e. around €295bn) over the 2014-2020 period.

These direct payments are themselves made up of 2 categories:

- Green payments, which are to represent 30% of direct aid, reflect the EU’s determination to continue “greening” the CAP. These are per-hectare payments conditional on compliance with three agri-environmental practices: crop diversification, maintenance of permanent grassland and preservation of at least 5% of Areas of Ecological Interest (hedges, trees, ponds, ditches, buffer strips, etc.).

- The remaining 70% are “basic” payments, allocated on the basis of farm area. 3 .

The second pillar aims to promote rural development, and can be seen as the CAP’s social and environmental pillar. It is characterized by greater flexibility than the first, in that regional, national and local authorities can formulate their own rural development programs from a European “menu of measures”. Examples of the types of measures financed include: compensatory allowance for natural handicaps, investment aid, start-up aid for young farmers, support for tree planting for agroforestry, support for cooperation or knowledge transfer between farmers. This pillar can also include measures to revitalize rural areas not directly linked to the agricultural sector (e.g. investment in basic services or village renovation, such as broadband, tourism infrastructure, etc.).

Finally, unlike the first pillar, which is fully financed by the Union, the second pillar must be co-financed by the Member States.

A new system that still fails to meet the objectives of social justice and environmental protection

In January 2019, the French Court of Auditors made a bitter assessment of the distribution of CAP aid in France. 4 . It notes that ” expenditure on direct aid from the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) (€7.8 billion per year on average from 2008 to 2015 for France) suffers from inadequate evaluation and steering by objective, that the method of distributing this aid, a factor in major inequalities, no longer has any relevant justification and, finally, that the effects of this aid are, at best, uncertain, whether in terms of farmers’ income, the economy of farms or the environment “.

The Court criticizes the highly unequal distribution of aid. In 2015, it says:“10% of beneficiaries (33,000 farmers) received less than €128 per hectare in decoupled direct aid (basic payment entitlements), while at the other end of the distribution 10% of beneficiaries received more than €315/ha.” The way direct aid is distributed favors large farms and those with the most profitable activities. Thus, in 2015,“the amount of average direct aid per farmer for the largest structures (€22,701) was 37% higher than that for the smallest farms (€16,535), all specializations combined“.

This uneven distribution of CAP aid is far from being France’s prerogative, as the graph below shows.

Source CAP Atlas (2019)

On the environmental front, work carried out by the European Court of Auditors, the Conseil général de l’alimentation, de l’agriculture et des espaces ruraux (General Council for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas) and the academic world shows that the effects of greening are considered limited, if not nil, due to excessively weak requirements and exemption schemes.

So why have all the reforms undertaken since 1992 to green the CAP failed? The commitments required were often difficult to manage and verify. At the same time, governments, under pressure from farmers’ unions, relaxed environmental constraints or introduced numerous exemptions. Farmers have often fought against environmental measures that modify their practices and initially destabilize the financial equilibrium of the farm. The most affluent farmers (field crops, industrial crops, etc.), who also benefit most from subsidies at present, see no point in committing to agro-ecological practices.

To initiate this transition in farming systems, in addition to subsidies, we also need training and extension on the transition of farming systems for farmers, technicians and also bank advisors, who will need to understand how to build up income in a different way. Research must also be adapted and oriented towards these agro-ecological models.

In terms of the environment, the work carried out by the European Court of Auditors shows that 5 the Conseil Général de l’Alimentation, de l’Agriculture et des Espaces Ruraux (General Council for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas) and the academic world, the effects of greening are considered to be limited, if not nil, due to excessively weak requirements and exemption schemes.

Why have all the reforms undertaken since 1992 to green the CAP failed? The commitments required were often difficult to manage and verify. At the same time, governments, under pressure from farmers’ unions, relaxed environmental constraints or introduced numerous exemptions. Farmers have often fought against environmental measures that modify their practices and initially destabilize the financial equilibrium of the farm. The most affluent farmers (field crops, industrial crops, etc.), who also benefit most from subsidies at present, see no point in committing to agro-ecological practices.

To initiate this transition in agricultural systems, in addition to subsidies, we also need training and extension on the transition of agricultural systems, aimed at farmers, technicians and also bank advisors, who will need to understand how to build up a farm’s income in a different way. Research must also be adapted and oriented towards these agro-ecology models.

New reform after 2020: will the environment finally be taken into account?

A new CAP reform is currently being negotiated. Initially scheduled for January 2021, the new CAP is not due to come into force until 2023, due to delays in negotiations. 6 .

Budgetary aspects

The budget allocated to the CAP is negotiated within the European Union’s 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which sets the maximum amounts the EU will be able to spend each year to finance its major policies (single market, environment, migration and border management etc.). In July 2020, the heads of state and government reached an agreement 7 bringing the EU budget over the period to €1074 bn, to which must be added the €750 bn of the Next Generation EU recovery plan, decided in the wake of the COVID 19 pandemic.

Of this, the CAP budget amounts to €336.4 billion (bn), of which €258.6 bn is for the first pillar (mainly direct payments) and €77.8 bn for the second pillar (rural development). This represents a decrease of around 12% compared to the 2014-2020 budget period 8 .

At the same time, the share of agricultural expenditure in the European Union budget continues to fall 9 whereas the CAP accounted for 66% of the Union’s budget in the early 1980s, it accounts for just 37.8% for the 2014-2020 period, and around 35% for 2021-2027.

Beyond the financial aspect, the heart of the reform concerns the CAP implementation model, focused on results and subsidiarity, which gives Member States a much greater role in the deployment of agricultural interventions. In future, the Union should set the essential parameters (CAP objectives, basic requirements, main types of intervention under the first and second pillars), while the Member States should draw up multi-annual strategic plans to achieve the specific objectives and figures agreed jointly.

On the environmental front, the future CAP intends to raise its standards. Under the 1st pillar, a system of voluntary “ecological programs” is being introduced. The idea is to get farmers more involved in implementing environmentally-friendly practices, such as organic farming, carbon storage, environmental certification, etc. The success of this measure will depend on the budget allocated. In November 2020, the share of the budget allocated to these ecological programs is still to be defined by the member states.

To qualify for direct payments, farmers will have to comply with stricter environmental standards. Green payments” will disappear, and the 3 criteria that triggered these payments (maintenance of permanent grassland, diversity of crop rotation and maintenance of areas of ecological interest) will be integrated into the eco-conditionality of aid (to be respected by all types of direct payment).

Echo schemes are the CAP’s new tool for going greener. The idea is to remunerate farmers for services rendered to the environment, echoing the concept of payments for environmental services (PES) that has been emerging in recent years.

The new green architecture would be much more flexible in its design and management, entrusted to national authorities. Once again, the aim is to take greater account of environmental and agricultural product quality issues. But the new reform also gives a greater role to Member States. It is up to them to set the programs needed to achieve the Union’s objectives. In France, we can expect a great deal of resistance from the majority trade unions, particularly in the context of the health crisis.

A number of studies, however, cast doubt on the effectiveness of the new CAP in meeting the European Union’s ecological objectives, be they the Green Deal recently launched by the new Commission, or its climate targets. Here, for example, are the conclusions of a recent report by researchers at INRAE and the AgroParis Institute, commissioned by the European Parliament’s AGRI Committee.

-EU farming and food practices fall far short of the ambition, purpose and quantitative targets of the Green Pact for Europe with regard to climate, environment, nutrition and health in this sector -To reverse these current unfavorable trends, it is urgent to significantly strengthen many of the CAP’s technical provisions, in particular those concerning cross-compliance requirements and measures relating to ecological programs, and those designed to improve the governance of the CAP, notably by making the achievement of objectives legally binding and improving their implementation, communication and monitoring. It is also essential to complement CAP regulations with a comprehensive and coherent food policy, including diet-based interventions.”

Find out more

- European Parliament factsheets on the CAP

- European Commission website: history of the CAP, how it works today, current reforms, budget, etc.

- The French platform Pour une autre PAC (For another CAP) bringing together farmers’ organizations and NGOs

- The CAP Atlas, issues and challenges facing European agriculture in pictures (2019)

- Source: Les disparités du revenu agricole, Revue d’économie rurale, Lucien Bourgeois 1994. ↩︎

- Rica France: standard tables 2018 (Jan. 2020). “Disposable income” is one of the farm accounting data that comes close to what net wages represent for salaried employees (notably because the farmer’s social contributions have been removed). ↩︎

- In reality, the system is more complex: the CAP allows Member States to choose to allocate the remaining 70% of direct aid between “basic payments” and various other categories of aid (with capped amounts) such as aid for young farmers (up to 2% of aid) or for less-favored areas (up to 5%), or coupled production payments (up to 15%). ↩︎

- Direct aids from the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGGF) | Cour des Comptes (2019) ↩︎

- European Court of Auditors: Special Report n°21/2017 ” Greening: increased complexity of the income support scheme and still no benefit for the environment “; Special Report n° 13/2020 “Biodiversity of agricultural land: the CAP’s contribution has not halted the decline“. ↩︎

- The European Commission presented three texts specifying the organization and objectives of the new CAP on June 1, 2018. In October 2020, the

European Parliament on the one hand, and theAgriculture and Fisheries Council bringing together the relevant ministers from EU member countries on the other, adopted their positions on the reform. All that remains now is to implement the negotiations between these two bodies. ↩︎ - On the European Commission’s website, find out about the various stages in the negotiations surrounding the 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework (MFF). Consult the Conclusions of the exceptional European Council of July 16-21, 2020, which set the overall framework for the MFF. Following the European Parliament’s rejection of the European Council’s proposal, new negotiations got underway, culminating on November 10 in a political agreement increasing the MFF by €16bn (from €1074bn to €1090bn). This political agreement still has to be voted by the Parliament and the Council. ↩︎

- The budget allocated to the CAP for the EU 27 (thus excluding the UK) over the 2014-2020 period amounted to €382.8 bn. Source: European Parliament Factsheet – The CAP in figures (table 1). Figures for the 2021-2027 CAP budget can be found in the Conclusions of the exceptional European Council of July 16-21. ↩︎

- which is one of the European Commission’s stated objectives. ↩︎