This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The 2008 financial crisis prompted financial supervisors at the G20 summit in Pittsburgh in September 2009 to propose specific standards for the largest international financial institutions. SIFIs (Systemically Important Financial Institutions) are defined as institutions whose “disorderly failure, due to their size, complexity and systemic interconnectedness, would cause significant disruption to the financial system as a whole and to economic activity”.

Gaëtan Le Quang and Rose Portier have reviewed and commented on this sheet.

What is a systemic bank?

Systemic banks are those whose failure would be likely to cause a contagious collapse of the financial system as a whole. They therefore present a systemic risk (see the module on the role and limits of finance), all the more serious as the impact is not limited to the financial sphere, but spreads to the rest of the economy. This is why they are also referred to as “too big to fail” banks, meaning they are too big for the public authorities to allow them to fail, which poses a number of problems, as we shall see later.

Financial Stability Board (FSB)

The FSB is an international organization whose mission is to assess global financial vulnerabilities, put forward proposals to address them, and promote cooperation between different (national or international) financial supervisory authorities. Created at the G20 summit in London in April 2009, the Financial Stability Board is the successor to the Financial Stability Forum. Hosted by the Bank for International Settlements, the FSB’s members include representatives of national and international supervisors and regulators, as well as financial institutions. The FSB’s decisions and recommendations are not legally binding. Its purpose is to define internationally-agreed policies and minimum standards, which its members undertake to apply and implement at national level.

The Financial Stability Board, in conjunction with the Basel Committee, established the methodology for defining G-SIBs, adopted at the G20 meeting in Cannes in 2011 and adjusted in 2013. Each international systemic bank is assigned a score from 1 to 5 based on a set of quantitative indicators covering not only their size, but also their degree of internationalization and interconnection with other financial institutions, as well as the complexity and nature of their activities (substitutability of the services they provide).

This methodology has been incorporated into the various national laws. In Europe, this was done with the CRD IV directive.

On this basis, the Financial Stability Board, in consultation with the Basel Committee and national authorities, has drawn up an annual list of G-SIBs since 2011. At the end of 2024, this list included 29 banks:

- 7 systemic banks in the euro zone, 4 of which are French (BNP Paribas, BPCE, Crédit Agricole and Société Générale, plus Deutsche Bank in Germany, ING in the Netherlands and Santander in Spain),

- 8 in the USA (JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Bank of New York Mellon, Morgan Stanley, State Street, Wells Fargo),

- 5 in China (Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and the Bank of Communications (BoCom) in Hong Kong),

- 3 in the UK (HSBC, Barclays, Standard Chartered),

- 3 in Japan (Mitsubishi UFJ FG, Mizuho FG, Sumitomo Mitsui FG) ,

- 1 in Switzerland (UBS),

- 2 in Canada (Royal Bank of Canada, Toronto Dominion).

In 2024, no systemic bank had a score of 5 (representing the highest risk).

Finally, it should be noted that while this fact sheet focuses on systemic banks at international level, the authorities also list systemic banks at national level, i.e. banks whose potential difficulties would have a very negative impact on the entire banking and financial sector of the country or zone in question. These are known as

Why are systemic banks a problem?

By definition, systemic banks pose the risk of a financial crisis.

The first reason is obvious, and has to do with the very concept of a systemic bank. By virtue of their size, complexity, the internationalization of their activities and structure, and their degree of interconnection with other financial institutions, they put the international financial system at risk. It was the collapse of the US bank Lehman Brothers that triggered the 2008 financial crisis by materializing systemic risk. The consequences affected not only finance, but also the real economy. The banking panic led to a credit crunch, with a sharp reduction in lending to businesses and individuals. The contraction of the real economy was of the order of 10% of GDP in advanced economies, with all the consequences this implies not only in social terms, but also in terms of the ecological transition, which has been postponed.

Public authorities intervened on a massive scale to prevent the financial system from collapsing: central banks injected liquidity into the paralyzed interbank market (see the section on “unconventional” central bank tools, in the module on money), while governments assumed responsibility for bank losses (via loans or capital injections). The budgetary cost of rescuing the banks can be estimated at 23 billion euros for France, 38 billion euros for Germany, 15 billion euros for Belgium, and between 40 and 45 billion euros each for Spain and Ireland. 4 .

The financial crisis led to a sharp rise in public debt, not only as a result of support for the banking sector, but also and above all as a result of the economic consequences of the crisis, which in the years that followed led to a fall in tax revenues and an increase in expenditure (unemployment, minimum social benefits). In Europe, this rise in public debt led in particular to the development of disastrous fiscal austerity policies (see the module on public debt) aimed at restoring public accounts.

Banks that are too big to fail “Profits are for the banks, risks are borne by governments as a last resort

As explained in a Senate report, “because of their very large size, the extreme density of the financial links that bind them to the rest of the economy, or the indispensable or non-substitutable nature of their activity, it is generally accepted by investors that the public authorities will never let them default (“too big to fail”). Their shareholders, customers and creditors are thus spared the risk of loss or bankruptcy: the prospect of default is averted by the virtual certainty that the state will intervene to support the institution as a last resort (“bail-out”).” 5

In addition to the partial guarantee of customer deposits valid for all banks 6 systemic banks benefit from an implicit public guarantee: governments and central banks cannot allow them to fail, as they would risk dragging the entire financial system down with them.

On the one hand, this implicit public guarantee distorts competition in the banking industry, making it easier for systemic banks to obtain cheaper financing on the financial markets than smaller banks.

Secondly, and more importantly, this creates a situation of “moral hazard”: the protection they enjoy encourages them to take more risks (and therefore earn higher returns when things are going well), given that in the event of a crisis it is the community that will bear these risks. In the run-up to the 2008 crisis, systemic banks were able to generate considerable returns on equity ( ROE) of between 10% and 20% a year. 7 . These gains were “privatized” in the form of dividend distributions to shareholders and very generous remuneration packages for executives and traders. When the crisis came, however, the losses were “socialized”. More fundamentally, the advantages conferred on systemic banks by this implicit guarantee may encourage a race to the top: becoming “too big too fail” seems to offer many advantages from a private point of view, even if the risks to the community are considerable.

In addition, these systemic banks are closely linked to shadow banking. shadow banking (the term used to describe all those entities whose activities are very similar to those of banks, but which are much less regulated. In this way, the implicit public guarantee enjoyed by systemic banks is at least partly indirectly extended to the shadow banking system.

Some estimates of the implicit guarantee provided by governments to banks that are too big to fail?

In a report published in 2014 15 the IMF evaluated these implicit subsidies using different calculation methods. For 2011-2012, they are estimated at between $100 and $300 billion for the euro zone, where banking concentration is highest; between $15 and $70 billion for the United States; between $20 and $110 billion for the United Kingdom; and between $25 and $110 billion for Japan.

According to a Senate report 5 the implicit guarantee granted to the four French systemic banks would represent 48 billion euros in induced benefits, compared with the almost 18 billion euros in total profits generated by these major banking establishments.

Banks that are too big to manage “

” Too big to manage ” is the line of defense adopted by some systemic bank executives during financial scandals. Stuart Gulliver, CEO of HSBC, for example, used this argument in 2015 when his bank found itself at the heart of a tax evasion scandal. Beyond the anecdote, the multiplication of financial scandals

The inadequacy of specific measures applied to systemic banks

In the wake of the 2008 crisis, two main measures were adopted to improve the sustainability of the banking sector.

Tighter capital requirements

Prudential regulations, stemming from the Basel Accords, require banks to comply with a solvency ratio: they must hold a certain amount of equity capital corresponding to a percentage of their risk-weighted assets. The aim is to ensure that they are able to absorb losses caused by borrower default (or by the devaluation of other assets). Following the crisis, prudential ratios were strengthened 11 and additional capital requirements were imposed on systemic banks (to a greater or lesser extent, depending on their systemicity score as indicated in the list maintained by the Financial Stability Board – see point 2).

Bank recovery and resolution mechanisms

These are a set of regulatory mechanisms designed to specify the terms and conditions of public intervention in the event of a bank failure, in order to protect savers’ deposits, avoid a bailout by the state (and therefore taxpayers) and prevent contagion to other banking establishments. It should be noted in passing that such measures are put in place to compensate for the fact that capital requirements may not be sufficient to prevent a bank’s failure.

At the heart of these mechanisms are the so-called “bail-in” measures, which aim to bail out banks internally rather than through the state (“bail-out“) in the event of failure. In this case, the bank’s shareholders and creditors holding securities that can be discounted or converted into shares are the first to be called upon to contribute.

This type of instrument was introduced in the United States as part of the Dodd Frank Act and in Europe as part of the Banking Union. Initial experience of the use of these tools by Italian banks, and in particular Monte Dei Paschi di Siena, shows their limited effectiveness. 12 .

15 years after the financial crisis, systemic banks are still “too big too fail

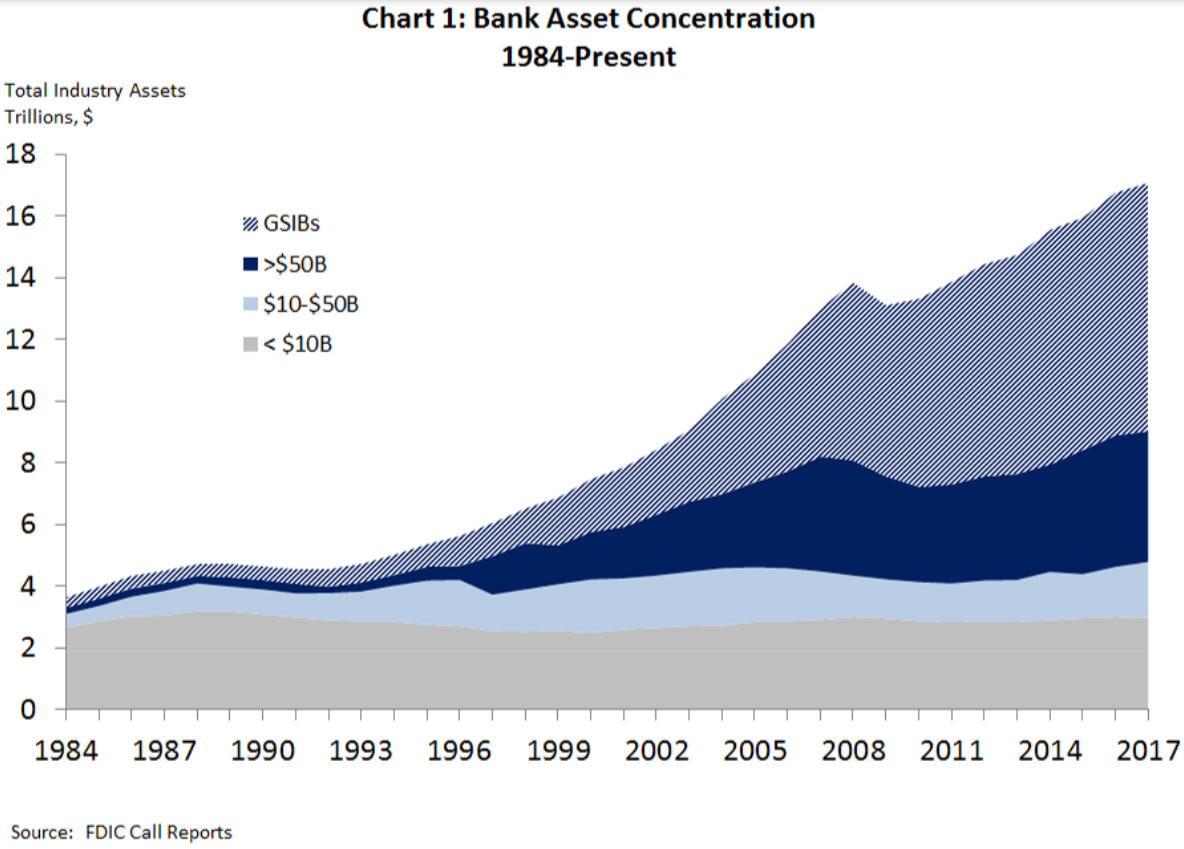

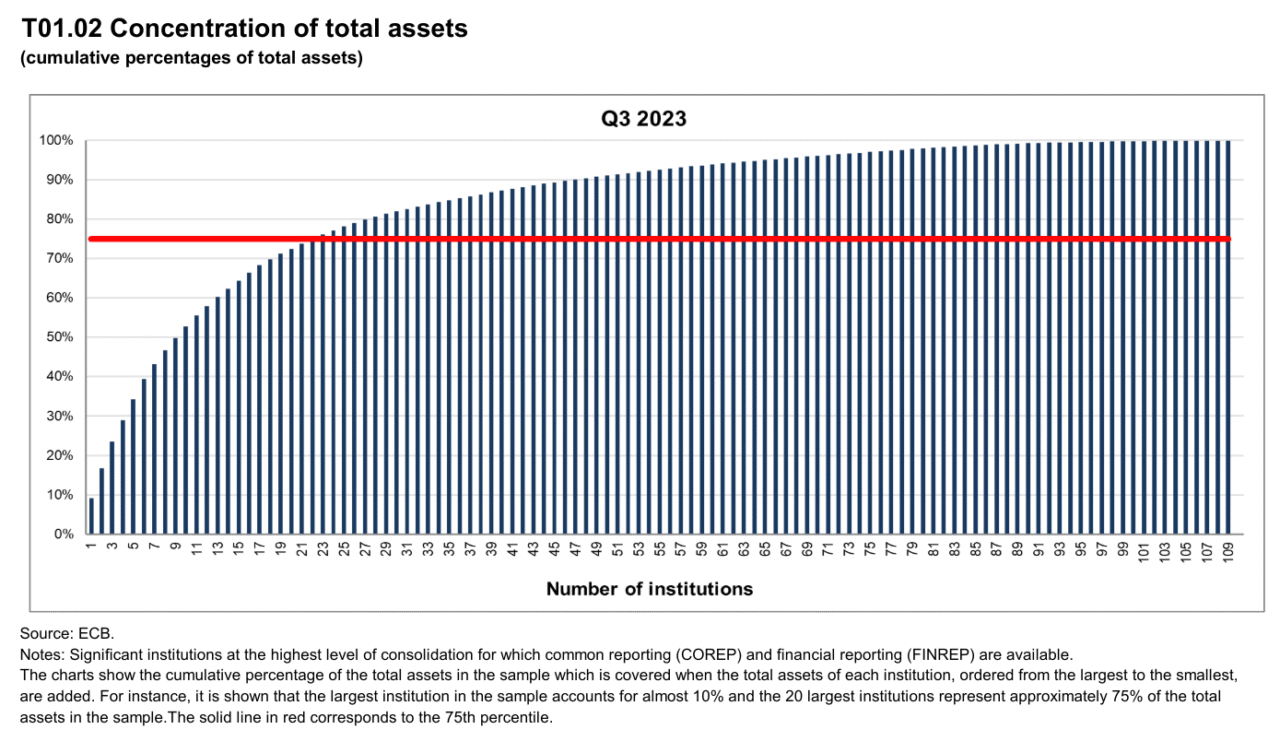

Although systemic banks are now clearly identified and taken into account in the rules governing banking activity, this has not fundamentally changed the situation. These banks are still very large, very interconnected and very international. This can be seen both in Europe (see box below) and in the USA (see chart below from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, one of the US regulatory bodies).

Europe’s high concentration of banks

As part of the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the ECB is responsible for supervising the largest banks (known as Significant Institutions – SIs) in the euro zone. 13 and publishes quarterly statistics on this subject.

The graph below shows the cumulative percentage of total IS assets when the assets of each institution are added up from largest to smallest. For example, the largest European bank accounts for 10% of total IS assets. The 8 European G-SIBs account for almost 50% of total assets.

Source Supervisory banking statistics – Third quarter 2023 (p4).

Post-crisis measures have not been aimed at reducing plant size and industry concentration

The rules and regulations put in place have not explicitly aimed to limit the size of institutions, to reduce their market power and thus the concentration of the sector, or to limit connections between financial institutions. Attempts to separate banking activities (in particular retail and investment banking), which could have had an effect on both the size of institutions and the risk of contagion, have been unravelled, riddled with exemptions that ultimately leave the structure of systemic institutions intact.

As the authors of a Terra Nova report point out 16 which takes stock of banking and financial reforms ten years after the 2008 crisis, it is necessary to change the idea in the minds of governments and public regulators that “the size of banking establishments is synonymous with robustness and greater competitiveness. For decades, large banks have been seen as national champions whose own interests are sometimes confused with those of the community. Yet size is one of the major criteria for the systemicity of banking groups. The community’s interest lies less in the presence of systemic behemoths in a position to extract rent at its expense, than in an ecosystem of banks of varying sizes with business models geared to the needs of the real economy.”

Find out more

- The list of systemic banks

- The dashboard maintained by the Basel Committee shows the scores of each bank.

- Explanation of the methodology used to designate G-SIBs

- Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran, Thomas Renault, “10 years after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, has systemic risk declined?”, Lettre du CEPII, (2018).

- Source: Financial Stability Board, Policy Measures to Address Systemically Important Financial Institutions, 2011 ↩︎

- The way in which systemic banks are referred to varies from one jurisdiction to another. For example, they are called EISm (Entités d’importance systémique mondiale) in French terminology, and G-SIIs(Global Systemically Important Institutions) in European terminology. These different names sometimes correspond to different methodologies for identifying them. In this note, we use the terminology employed by international institutions: the Basel Committee and the Financial Stability Board. For further details, see the ACPR website . ↩︎

- Adopted in June 2013, the CRD4/CRR legislative package transcribes the Basel 3 Accords and standardizes the prudential supervision arrangements for European banks. The package comprises a regulation

(Regulation 575/2013 on prudential requirements for credit institutions and investment firms) and a directive(Directive 2013/36/EU on the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions, and on the prudential supervision of credit institutions and investment firms). Article 131 of the directive sets out the methodology for identifying systemic banks and the competent institutions. ↩︎ - See Pierre-Henri Leroy, La conjuration bancaire, VA Editions, 2020, p 123 ff. ↩︎

- Projet de loi de séparation et de régulation des activités bancaires, Avis de la commission des affaires économiques du Sénat, Annex V – La notion de garantie publique implicite, 2013. ↩︎

- In France, it amounts to a maximum of €100,000 per depositor, via the Fonds de garantie des dépôts et de résolution. ↩︎

- For example, here are the ROEs of some major European banks in 2007: Banca Monte dei P. S. 17.35%; BBVA 25.53%; BNPP 14.55%; Deutsche Bank 17.89%; HSBC 16.34%; Lloyds Banking Group 27.75%; Santander 18.42%. Source: Reforming the structure of the EU banking sector – Liikanen report, 2012, table A.3.5, p.127. ↩︎

- The Libor, Euribor, Tibor and Forex scandals have undermined the integrity of the markets, as have the scandals surrounding toxic loans to local authorities and the involvement of banks in tax evasion schemes… ↩︎

- Joël Moret-Bailly, Hélène Ruiz Fabri, Laurence Scialom, “Conflicts of interest, the new frontier of democracy”, Terra Nova, 2017 ↩︎

- For more on this subject see Joël Moret-Bailly, Hélène Ruiz Fabri, Laurence Scialom, “Conflicts of interest, the new frontier of democracy”, Terra Nova, 2017; Laurence Scialom, La fascination de l’ogre, ou comment desserrer l’étau de la finance, Fayard, 2019, p.91 et seq. ↩︎

- The solvency ratio, the central tool of prudential regulations, has been strengthened, and other ratios (leverage ratio, liquidity ratio) have been introduced. ↩︎

- This example is detailed on p25 of the note 10 ans après… Banking and financial reforms since 2008: progress, limitations, proposals Terra Nova (2018) ↩︎

- Other EU countries may decide to participate via the establishment of “close cooperation” between their national prudential supervisory authority and the ECB. This is what Bulgaria and Croatia did in October 2020. ↩︎

- See the“Other Systemically Important Institutions (O-SIIs)” page of the European Banking Authority. ↩︎

- Implicit public subsidies to big banks persist despite reforms, Global Financial Stability Report, IMF, 2014. ↩︎

- Vincent Bignon, Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran, Laurence Scialom, 10 ans après… Bilan des réformes bancaires et financières depuis 2008: avancées, limites, propositions, Terra Nova, 2018. ↩︎