This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Published in 1817 in a book1 by economist David Ricardo, the theory2 of comparative advantage is one of the best-known and most widely-used arguments in favor of trade liberalization. While this theory was historically successful – and is still used by advocates of free trade – it is based on a very flimsy model.

We won’t go into detail on the historical context in which this theory was produced, nor on its subsequent developments. Let us simply recall that Ricardo’s comparative advantages were intended to refute Adam Smith’s theory of absolute advantages. According to this theory, free trade would economically eliminate any country that could not produce goods more cheaply than its competitors.

Nor will we go into all the – vast – debates on international trade (to which we will devote a module shortly). We’ll confine ourselves here to highlighting the weakness of Ricardo’s model. However, its presence in teaching and economics courses is essential, for a reason well formulated on the Partageons l’Éco website: “Despite the fact that the theory of comparative advantage has come in for a certain amount of criticism, it remains one of the most useful analytical frameworks for understanding international trade.”

We’ll see here that this “theory” is simply inconsistent.

Ricardo’s initial argument

David Ricardo wanted to defend free trade, which allowed wheat prices in England to fall by importing cheaper foreign wheat. Indeed, wheat production was protected from international competition by the Corn Laws, which Ricardo was a staunch opponent of, believing them to be detrimental to the industry’s economic performance.

At the time, the prevailing theory of international trade was Adam Smith’s theory of absolute advantage, according to which a country whose production was less costly in absolute terms than that of another was necessarily a winner from free trade. From then on, trade liberalization could be entirely unfavorable to a country with higher costs for all its products.

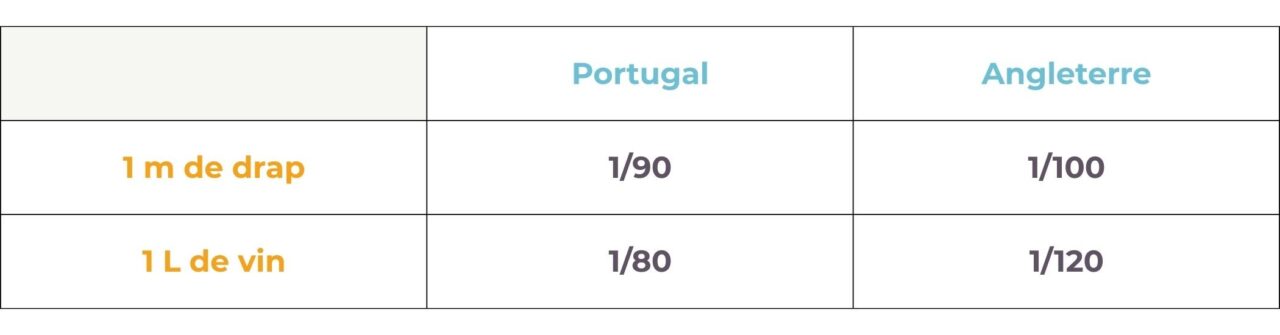

Ricardo based his argument on the competition between Portugal and England, each producing cloth and wine. He assumes that production costs are higher in both cases in England. He shows that, in this case, free trade still results in a gain for both countries, as each has an interest in specializing in the sector in which it is “relatively best”. A little math goes a long way. Suppose, for example, that productivity (in labor units divided by labor hours) is as follows3:

Illustration of Ricardo’s calculation of comparative advantage

In this example, Portugal is superior to England in wine and cloth, but its comparative advantage in wine is greater than in cloth. The opening up of trade between the two countries will lead Portugal to specialize in wine (since this is where it will make the greatest gain in trade) and leave England to specialize in cloth. Before the opening of trade between countries, to produce 2m of cloth required 190h of work (100+90), and 200h of work for 2L of wine (120+80), i.e. a total of 390 hours. After opening up trade, the cumulative time will be 360 hours, with England saving 20 hours and Portugal 10 hours compared with the previous situation.

Ricardo concludes that free trade does not condemn the less productive to lose out. Even if a country were the “best at everything”, it would not capture all trade, since it would be in its interest to specialize in the niches that were most profitable for it. To formulate this argument in an even more accessible way, Ricardo uses it in the case of two workers:

“Suppose two workmen both skilled in making shoes and hats: one of them can excel in both trades; but in making hats he prevails over his rival by only a fifth, or 20 percent, while in working on shoes he has an advantage over him of a third, or 33 percent. Would it not be in the interest of both if the most skilful worker were to devote himself exclusively to shoemaking, and the least skilful to hatting?”2

This comparison is very effective because it illustrates macroeconomic reasoning with an example from microeconomic life.5It’s easy to understand, and all the more convincing in view of the fact that the specialization of companies and their focus on their strong points is a mantra of all management schools – and not without foundation, in this respect.

Ricardo’s little model also has an undeniable pedagogical capacity. It makes it clear that if labor were distributed as suggested by comparative advantages6the total output would be much higher than if it were distributed according to absolute advantages.

The obvious weaknesses of Ricardo’s “demonstration

Ricardo is credited with bringing this notion of comparative advantage to light. But this “model” (for it is a small mathematical model, however rudimentary) is based on questionable assumptions and simplifications, and is obviously far from representing reality. Let’s start with the two most obvious criticisms.

On the one hand, it’s not because countries would theoretically benefit from specializing in this way that they will do so, assuming that all customs barriers are lowered. To imply that the specialization considered optimal by Ricardo would take place “mechanically” because it would be in the interest of nations is, of course, very hasty. In reality, open trade means competition between companies, not between public authorities capable of allocating labor forces. So there’s nothing to say that the result of open trade is in line with the small model’s calculations.

On the other hand, in Ricardo’s reasoning, laborers and capital (even if the latter are not explicitly mentioned in the calculation) are the most important elements of the production process.7they are nonetheless indispensable) are assumed not to move. If English capitalists invest in cloth in Portugal – because for them it’s a better investment – English production will collapse. Ricardo was well aware of this argument and tried to answer it8:

“There are many reasons why English capital should not leave the country, such as “the fear of seeing capital annihilated outside, of which the owner is not the absolute master”, “the natural repugnance which every man feels to leave his homeland and his friends in order to entrust himself to a foreign government, and to subject old habits to new morals and laws”! “These sentiments, which I would be angry to see weakened, decide most capitalists to be content with a lower rate of profit in their own country, rather than seek in foreign countries a more lucrative use of their funds.”

The facts clearly prove him wrong: the opening up of international capital flows makes them mobile, and they don’t deprive themselves of opportunities to make money.

Questionable assumptions and extreme simplifications

These first two criticisms can be completed by highlighting a series of unexplained but questionable postulates:

- Productivity gains would benefit society as a whole.

There’s nothing obvious about this. If less labor is needed to produce the same quantities of cloth and wine, no economic law guarantees who will benefit from these gains. It could be imagined, for example, that total production remains constant and workers are laid off.

- The improvement in the interests of both countries is measured in terms of labor productivity gains.

At the time, for Ricardo and his peers, the fight against the scarcity that haunted everyone – and the famines that could ensue – could only be won by reducing the share of human time in production, which was one of the limiting variables. It’s understandable that an economist would then consider that the productivity gain linked to exchange could represent the indisputable benefit of exchange. Today, this is no longer the case: social well-being is not the automatic result of these gains, and issues of energy, natural resources and pollution (including greenhouse gas emissions) are – at last – being taken into account.

- Countries (and their leaders) think in narrow economic terms, ignoring geopolitical issues and strategic dependencies.

- Product prices reflect their labor content; this is the “labor-value” theory, shared by Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

This theory is patently false. A selling price depends on many parameters: the competitive situation and the relationship between supply and demand, on which company margins partly depend; cost prices, which include purchases, taxes, social charges and subsidies; currency parities, and so on.

Let’s move on to simplifications. Of course, in economics, no mathematical model can represent the extraordinary complexity of reality: it therefore requires a certain number of simplifications. But the simplicity of Ricardo’s model is extreme. Here are just a few of the assumptions implicit in Ricardo’s model:

- There is only one factor of production: labor, which is homogeneous.9mobile within the country but, as we said, immobile internationally.

- The model involves only two countries, the home country and the foreign country.

- They produce only two types of goods: wine and cloth, which are assumed to be identical whether they are made in one country or the other.

- Transport costs are zero.

- Yields are constant.

- The respective values of the exchange currencies are assumed to be stable, and the currencies valued so that productivity gains translate into monetary gains.

Although more complex models have been developed10 to remove some of these overly restrictive assumptions, the “theory of comparative advantage” remains a benchmark.

The Heckscher-Ohlin model

Swedish economists Eli Heckscher (in 1919) and Bertil Ohlin11 (1933) developed a model known as the HO model, completed in the 1940s by Paul A. Samuelson and Wolfgang S. Stolper. They “improved” on Ricardo’s model, by introducing two factors of production (capital and labor) and differences in each country’s endowments of factors of production, which they showed to be the source of each country’s specific advantages.

For the rest, this model is as simplistic as Ricardo’s. Here are some of the assumptions on which it is based:

– Production takes place at constant returns to scale;

– Competition is pure and perfect;

– Production factors are not available in the same quantities in every country;

– The goods produced require more or less capital or labour respectively;

– Technology is identical in both countries: if a good requires more capital than labor in one country, this is also the case in the other.

Heckscher and Ohlin conclude from the model that each country produces and exports the good for which its production factor is relatively most abundant. Let’s take an illustrative example:

Two countries (Germany and Bangladesh) produce two goods (cars and T-shirts) using two production factors (capital and labour). Cars are capital-intensive, T-shirts labor-intensive. Germany is capital-intensive, Bangladesh labor-intensive. If countries start exchanging products, each specializes in the good for which it has a more abundant factor of production: Germany in cars because it has more capital than labor, Bangladesh in T-shirts because it has more labor than capital. Thanks to exchange, each country was able to export the good it produced “better” and import the other product. Each country obtained more goods than in a situation of autarky.

Conclusion

This little model is at the root of the idea that “Northern” countries have an interest in specializing in high value-added sectors and “Southern” countries in labor-intensive sectors, but it is just as questionable as Ricardo’s model.

Source This box draws heavily on the presentation on the BaSES Project website.

Conclusion

The “theory of comparative advantage” certainly played a key role in the abandonment of the12 England’s relative abandonment of its (albeit powerful) agriculture in favor of industrial specialization in the 19th century. Self-sufficient at the beginning of the 19th century, the country would depend on foreign countries for more than two-thirds of its food by the beginning of the following century. And more generally, as mentioned in the introduction, this “theory” remains the essential reference for economic reasoning on the question of international trade. Yet it is clear that this theory cannot be tested empirically, as none of the assumptions on which it is based are realistic. It is also clear that we cannot rationally deduce any prescriptive value from it. And yet…

- David Ricardo, Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817. ↩︎

- Sometimes called a theorem or a law, this is a very abusive way of naming this theory. ↩︎

- The figures are not exactly Ricardo’s, but the comparison between cloth and wine is one of the examples taken (see pages 85 ff. of Principles of Political Economy and Taxation David Ricardo, 1817). ↩︎

- Sometimes called a theorem or a law, this is a very abusive way of naming this theory. ↩︎

- Let’s not forget that any attempt to “micro-found” macroeconomics is tantamount to reducing the analysis of a complex system to the addition of individual behaviors, which necessarily leads to extreme and ultimately false simplifications. See our Guiding Ideas, and in particular the first one: “Economic life is part of nature and human societies.” ↩︎

- As economist Gilles Raveaud points out in his excellent blog post Libre-échange : et si le modèle de Ricardo était faux? (Alternatives Économiques, 27/01/2024), that it’s not a question of comparing the productivity of one country with that of another, but rather “the sectoral productivities internal to each country”. ↩︎

- They are in the Heckscher-Ohlin model explained in the box below. ↩︎

- Quotes from economist Gilles Raveaud, in his excellent blog post Libre-échange : et si le modèle de Ricardo était faux?, Alternatives Économiques, 27/01/2024. ↩︎

- In other words, a farm worker can become a weaver immediately and at no cost. The same applies to production infrastructures. Obviously, this is not how it works in real life. ↩︎

- See Wikipedia’s comprehensive article Comparative advantage. ↩︎

- Bertil Ohlin, Interregional and International Trade, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1933. ↩︎

- The Third World at an impasse, Paul Bairoch, Gallimard, 1992. ↩︎