This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Taking Nature into account in our economic reasoning comes up against a conceptual difficulty: how do we characterize (and manage) natural “goods”?

Put simply, environmental goods are neither “in essence” private, nor public. They are not private, because Nature does not belong to anyone; it takes a political act of the order of law for a piece of land or its subsoil to become the property of a person or entity – whether private or public. In the same way, Nature is “free”: she doesn’t charge for the services we enjoy, nor for the nuisances we inflict upon her. Introducing prices can only be done in a political way.

Natural goods and services are, in most cases, common goods.

The aim of this fact sheet is to provide a precise definition of the concepts of public, private and common goods, and to explain the difference between the four main types of goods.

The challenges and history of property classification

These distinctions are not just theoretical: they are key to safeguarding these assets and managing them in the most appropriate way. And the various options that have been devised are the subject of lively and legitimate controversy, often against an ideological backdrop: advocates of “commodification” are pushing for the privatization of natural assets, while others are pushing for their nationalization, and still others are acting as if these assets were infinite.

Let’s start with a quick review of the history of these concepts. At the birth of political economy and its formalization in the

As the state has asserted itself as an economic player, economists have turned their attention to public goods (those managed by a public administration). Paul Samuelson was the first economist to formalize the distinction between private and public goods 1 in 1954. At that time, the choice was between nationalization and privatization, and economists’ work focused mainly on infrastructure and public sectors (such as rail networks). In 1965, James Buchanan introduced and explored the notion of club goods. 2

Garret Hardin and the “tragedy of the commons”

In 1968, the economist Garret Hardin produced a highly acclaimed essay, The Tragedy of the Commons, published in Science. He wanted to demonstrate that management left to rational actors could only lead to its destruction. He imagines a common meadow where several herders graze their flocks. Each herder, in good homo economicus seeking to maximize his profit, adds more and more cattle. Although this is rational for each individual, collective accumulation leads to over-exploitation of the meadow. Eventually, the resource is destroyed, to everyone’s detriment. Hardin uses this metaphor to show that, without regulation, common goods (such as oceans, forests or the atmosphere) risk being degraded. He concludes that solutions such as privatization or collective regulation are needed to avert this tragedy.

Elinor Ostrom and the collective management of common goods

Elinor Ostrom, socio-economist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 3 played a major role in the analysis of the commons. She has shown that communities can manage these resources sustainably, without state intervention or privatization. She inventoried a series of “rules” that communities respect in order to do so (see box below).

Elinor Ostrom and the 8 rules for managing the commons

1. The boundaries of the commons and the conditions for accessing resources must be clearly defined. The beneficiary community must be limited, otherwise there is a risk that the resource will be exploited by everyone.

“As a commoner, I know how to recognize the resources I need to care for and the people with whom I share this responsibility. Commoner resources are those we create together, protect as gifts of nature, or those that anyone can use.”

2. There is no standard approach to managing the commons. The rules must be established and adopted by the local community, taking into account the ecological needs of the area.

“We use the common resources we create and those we take care of. We use the means (time, space, technology, quantity of a resource) available in a given context. As a commoner, I’m convinced of the proportionality of the ratio between my contributions and the benefits I receive.”

3. Decision-making must be participatory. People are more likely to follow the rules they have helped to put in place. So it’s crucial to involve as many people as possible in the decision-making process.

“We establish or modify our own rules and decide on our commitments ourselves; and every commoner can participate in this process. Our commitments are to create, maintain and preserve the commons with the aim of meeting our needs.”

4. Communes must be supervised and monitored. Communities must be able to ensure compliance with the rules in place. Each community member must take responsibility and be accountable for his or her actions.

“We ensure that these commitments are met ourselves, and sometimes we ask those we trust to help us achieve this goal. We constantly reassess the relevance and usefulness of our commitments.”

5. Penalties for non-compliance should be graduated, for example through warnings, fines etc. Indeed, Ostrom has observed that banning offenders generally arouses and nurtures resentment.

“We develop the appropriate rules for dealing with violations. We determine the legitimacy of the sanction and its type according to the context and seriousness of the violation.”

6. Conflicts must be resolved within the community, and each member must have easy access to resolution methods and processes.

“Every commoner must have the space and means to resolve conflict. We work to resolve conflicts among ourselves, in an accessible and straightforward way.”

7. Communes must have legal status, recognized and respected by local authorities, hence the importance of the right to organize.

“We decide on our regulations, and outside authorities respect that.”

8. Each community is part of a larger network. While some can be managed locally, others require greater regional cooperation. For example, an irrigation network may depend on a river, from which other communities also draw.

“We realize that each common is part of a greater whole. So better stewardship coordination and broader cooperation require the commitment of diverse institutions, working at different scales.”

Excerpt from Derek Wall, Elinor Ostrom’s Rules for Radicals – Cooperative Alternatives beyond Markets and States Pluto Press, 2017.

Source: Elinor Ostrom and the eight principles of commons management, Heinrich Böll Foundation Tunisia

Exclusivity and access: a complete typology of social properties

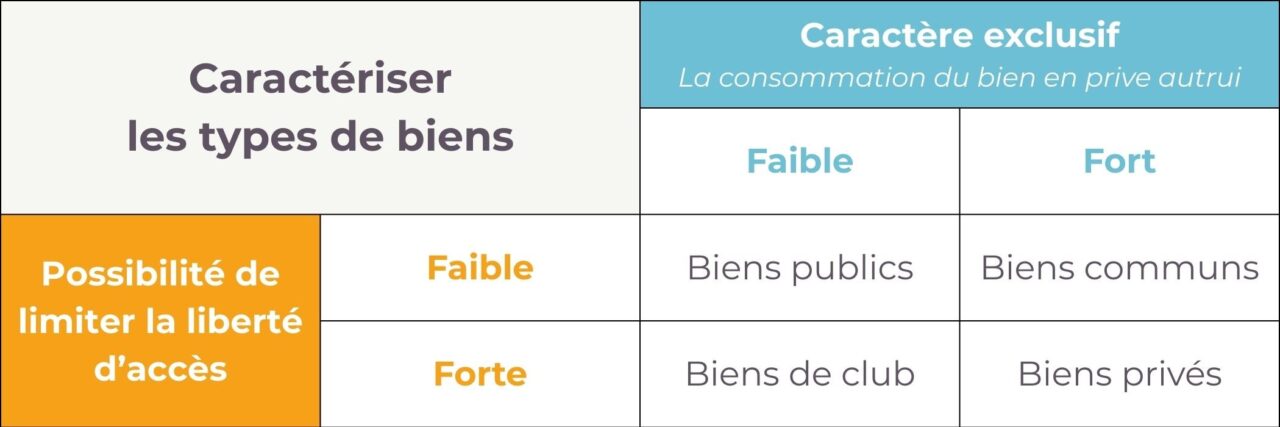

Two attributes characterize a social good, whatever it may be, and make it possible to establish a complete typology of social goods:

1) Whether or not consumption is exclusive. The use of a good is considered exclusive when the fact that one person “consumes” it deprives others of it. Eating this pear prevents your neighbor from tasting it. On the other hand, listening to an open-air concert does not prevent anyone else from enjoying the music. Economists also use the adjective “rival” for “exclusive”.

2) Whether or not it is open access. It’s difficult to prohibit fishing in the world’s oceans, so the fish that inhabit our oceans can be considered “open access”. On the other hand, to participate in a chess network, you usually have to pay an entry fee.

If we combine these two criteria – exclusivity and access – we obtain a typology of four property families:

a) Private goods are those whose consumption is exclusive and access to which can be restricted. An apple I buy at a fruit stall is a private good, as are a car, a telephone, a piece of clothing, and so on. In short, the vast majority of everyday consumer goods.

b) Public goods are those whose consumption is not exclusive and whose access cannot be limited. Sunlight is a public good (at least for a few billion more years…).

c) Club or “tribal” property are those whose consumption is not exclusive, but whose access may be limited. Playing chess in a chess network doesn’t prevent another person from playing, on the contrary: it gains a potential partner. On the other hand, access to the network may have to be paid for. Digital “tribal” goods are legion: the telephone, the Internet, social networks. Some (Wikipedia, free software, copyleft, etc.) are trying to organize themselves as commons, reinventing new relationships to property beyond the private/public dichotomy. 4

d) Finally, common goods are those whose consumption is exclusive but whose access cannot be restricted. Industrial deep-sea fishing breaks a series of trophic chains 5 This is leading to a rapid decline in fish stocks throughout the world’s oceans and seas. We can see that this notion also applies to shared ecosystem services: climate regulation benefits everyone, but everyone, by emitting greenhouse gases, degrades this regulation. Climate cannot be managed as a public good, nor as a private good.

Access to property is (more often than not) a choice

Before going any further, it’s important to note that the boundaries between these four categories are not imposed by natural necessity. For many goods, access does not characterize them as such, but is the result of social organization and social relations. The history of enclosures (see box below) has shown that goods considered commonplace by some social groups (in this case, peasants) can be privatized (by other social groups) by force.

In the same way, it is possible to manage common goods as club goods. Examples include green energy cooperatives, shared groups, collective gardens, fishing clubs…

A short history of enclosures

Enclosures refer to the process by which collective or communal farmland in England was fenced off and transformed into delimited private property.

In the Middle Ages, farmland was largely cultivated collectively under the open field system. Peasants had access to scattered plots and could also graze their animals on common land(commons).

As early as the 16ᵉ century, with the rise of the wool industry, the demand for wool increased considerably. Landowners began to fence off communal land for sheep grazing, considered more profitable than cereal crops. Under the Tudors (notably Henry VIII), laws were passed to limit these practices, as they led to social tensions and the displacement of peasant populations.

In the 18ᵉ and 19ᵉ centuries, hundreds of Enclosure Acts, were passed by the English Parliament, allowing the privatization of vast tracts of land. In crude terms, this was a massive spoliation of peasants by the landed elites, who profited from it: innovations such as crop rotation required centralized land management, which the enclosures favored. Agriculture became more productive and export-oriented. The industrial revolution was aided by this. Many small farmers were expelled from their land, losing their access to commons. They either had to become farm laborers, or migrate to the cities, supplying the labor force for the fledgling factories.

Rivalry, congestion and asset depletion

The exclusive or non-exclusive nature of a good’s consumption seems more “generic”, but it’s not always so clear-cut. For example, certain goods that are only weakly rivalrous can become rivalrous once a certain level of consumption is reached; this is the

Digital services and platform economies also demonstrate the difficulty of drawing precise boundaries between the market and the non-market; the “free” nature of the web nonetheless leads to the creation of colossal empires. In other words, there are market transactions, whereas digital platforms have the aspects of a public good (free access and non-rivalry). 6 But their apparent gratuity conceals the fact that the Internet is a club good (paid access) and that the platforms are paid for in other ways (notably through the exploitation of user data).

Conclusion

The distinction between 4 types of goods shows that it is possible (and desirable) to imagine alternatives to the usual private/public confrontation.

Find out more

- The commons versus private property? – Entendez-vous l’éco podcast, 2018.

- Gouvernance des communs, Pour une nouvelle approche des ressources naturelles, Elinor Ostrom, De Boeck, 2010.

- The Return of the Commons. La crise de l’idéologie propriétaire, Benjamin Coriat, Les Liens qui libèrent, 2015.

- Elinor Ostrom, Stockholm speech, on receiving the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics, C&F éditions, 2020.

- Composer un monde en commun, Gaël Giraud, Seuil, 2022.

- In his article The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1954. ↩︎

- In his article An Economic Theory of Clubs, Economica, 1965. ↩︎

- On the subject of the Nobel Prize in Economics, seeWhythe “Nobel Prize in Economics” is not a Nobel Prize like the others – Les Décodeurs, Le Monde (09/10/2023). ↩︎

- See Benjamin Coriat, The Return of the Commons. La crise de l’idéologie propriétaire Les Liens qui libèrent, 2015. ↩︎

- A food web is a set of interconnected food chains within an ecosystem. See Wikipedia page Food web. ↩︎

- See Michel Devoluy, L’économie : une science “impossible” science – Deconstructing to move forwardVerona, 2019. ↩︎