This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 quickly spread to the real economy, plunging many countries into the “Great Recession” with its attendant bankruptcies, mass unemployment and job insecurity. Largely unforeseen by economists 1 this crisis brought back to the fore the work of economists such as Irving Fisher (1867-1947) and Hyman Minsky (1919-1996), who had highlighted the intrinsically unstable nature of liberalized finance and the mechanisms of financial crises inherent in the functioning of financialized capitalism. The aim of this fact sheet is to summarize the deciphering of the mechanisms leading to this type of crisis.

The bull phase: Minsky’s “paradox of tranquility

At the start of the business cycle, technical progress and the conquest of new markets fuel sustained investment by companies. However, bank credit, which finances this investment, remains limited to agents whose expected earnings from these investments exceed the amount owed. Borrowers are solvent. Finance remains sound. As the expansion continues, optimism spreads to all economic agents. Risk aversion declines among both borrowers and lenders.

Risk aversion, a procyclical phenomenon

Risk aversion, i.e. the greater or lesser appetite of economic agents for taking risks, evolves over time: at certain times, they are risk-averse, while at others they are much less cautious. This evolution has a procyclical character: for the majority of players, risk aversion changes in the same direction as the economic climate, amplifying the financial cycle rather than cushioning it. In periods of expansion, risk aversion is low, leading all players to take on more and more risk. Conversely, when the cycle turns, risk aversion becomes very high: lenders and borrowers become wary, even of profitable projects.

Investment projects, previously considered risky, now appear acceptable. Lenders lend more readily and differentiate less between borrowers according to their level of risk.

2

. Households and businesses borrow more easily. Credit is booming in relation to income. Overindebtedness, i.e. excessive debt in relation to repayment capacity, is on the rise. Adair Turner notes that in the decades preceding the global financial crisis, private indebtedness grew much faster than GDP: private debt (household and corporate) rose from 50% of GDP in 1945 to 160% in 2007 in the USA; from 15% of GDP in 1964 to 95% in 2007; from 80% of GDP in 1980 to 230% in 2007 in Spain.

3

.

But this over-indebtedness is hidden. In fact, the rise in demand for assets 4 of real estate and financial assets increases their prices and gives all players a sense of security. Asset holders feel richer even if they are in debt (because they believe they can resell their real estate or financial securities for more than they bought them). Lenders feel protected, because they can sell the assets pledged as collateral in the event of borrower default.

This rise in the value of real estate and financial assets, combined with easy access to credit, boosts profits: by taking on debt, it’s possible to generate substantial capital gains with a minimal initial outlay (see sheet on leverage). Other investors take on debt not to invest in concrete projects, but to profit from rising share prices. In this case, the motivation for taking on debt is purely speculative. Pushed to excess, this behavior leads some agents to rely more on rising asset prices than on their own income to pay off their debt. The proportion of speculative and Ponzi finance (see below) increases sharply, weakening the entire financial system.

The three types of financial behavior identified by Minsky

– Sound or prudent finance: the return on investment is higher than the financial charges, and therefore covers interest payments and repayment of borrowed capital.

– Speculative finance: the return on investment pays the interest, but not the capital repayment, which relies on continuous debt renewal.

– Ponzi finance 5 This type of finance is characterized by the search for latent capital gains, i.e. the difference between the price at which the asset was purchased and its current market price. This type of finance is characterized by the search for latent capital gains, i.e. the difference between the price at which the asset was purchased and its current market price. When there’s a bubble, asset prices rise, and so do unrealized capital gains. But until the asset is sold, unrealised capital gains remain merely potential, i.e… unrealised.

This generalized appetite for risk is undermining credit markets precisely at a time when, on the contrary, agents believe that risk is minimal, since profits are high, inflation low and the cost of credit cheap. As we have seen, overindebtedness and financial fragility are hidden by rising asset prices. They develop when the economy seems to be doing well. This is what Minsky called “the paradox of tranquility”.

The bursting of the financial bubble

This interdependence between the credit market and the financial and real estate asset markets is at the heart of contemporary financial instability. It creates a vicious circle. Credit supply and demand both depend on rising asset prices, which in turn are fuelled by the credit drift. There is no longer any automatic adjustment mechanism in the credit market. In particular, rising interest rates no longer discourage excessive demand for credit.

The decoupling of rising financial asset prices from the capacity of the real economy to generate the income needed to repay them sooner or later leads to a stranglehold: investors whose only income comes from the real economy have to start repaying their debt. There comes a time, sometimes referred to as the “Minsky moment”, when these investors are forced to sell their financial assets to pay off their debt. If there are enough of them and/or if their exposure to debt is very high – in other words, if the divorce between the real sphere and the financial bubble is sufficiently pronounced – they will end up making all markets “sellers”, and thus driving down asset prices.

This reversal (which began in late 2007 with the bursting of the US real estate bubble, which quickly triggered the bursting of the stock market bubble) is catastrophic for speculative and Ponzi investors. Whereas they had counted on their financial gains to repay their debt, they in turn found themselves forced to sell to meet their financial obligations. The fall in share prices accelerated. It’s a crash. In 2008, 25% of market capitalization went up in smoke.

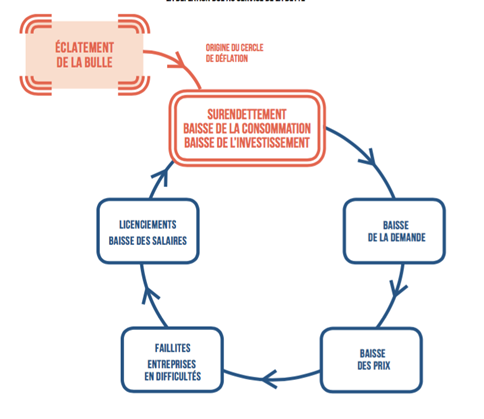

Deleveraging, recession, debt deflation

Once the speculative bubbles have deflated, the economy sinks into recession, which can lead to “debt deflation”, as the economist Irving Fisher theorized in the 1930s. The more indebted private agents are, the longer and more painful this phase will be. What’s involved?

Far from the optimism that prevailed during the euphoric period, economic agents are now looking to clean up their financial situation and reduce their debt. To do so, they are forced to cut back on consumption, postpone investment projects and even sell off assets that served as collateral for their loans, and whose price plummeted with the crash. These behaviours, rational and “good management” on the microeconomic level, have disastrous consequences on the macroeconomic level: they converge in the direction of a drop in aggregate demand and a fall in the general level of prices, which deepens the slump in activity. Several effects are helping to sustain and amplify the phenomenon.

- The effect of expectations: the fall in prices following the financial crash and the drop in global demand is reinforced by the expectations of economic players. Households and businesses are postponing their investment and consumption projects in order to benefit from more advantageous prices in the future.

- The distribution effect: repayments generate income transfers between creditors and debtors. However, creditors tend to save a larger proportion of their income. This reduces aggregate demand.

- Contraction of the money supply: repayment of loans corresponds to monetary destruction. If new loans don’t compensate for repayments, the money supply contracts, destroying purchasing power. In a depressed economy, risk aversion is dominant: banks lend less, and credit is more expensive.

The general pursuit of debt reduction thus has the opposite effect to that sought: the real value of debt increases. The nominal value of a debt is its amount, for example €100,000. But this amount means different things to different borrowers, depending on their income, assets and general price levels. In times of deflation, the real value of debt increases, because for the same amount of debt, you have to work harder or sell more and more (goods, services, real estate or financial assets) to pay it off.

This is the paradox identified by Fisher as early as the 1930s.

We then have the great paradox which, I submit, is the great secret of most, if not all, major depressions: the more debtors pay back, the more they owe. The more the ship of the economy leans, the more it tends to lean.

All these elements are self-perpetuating in a vicious circle that Irving Fisher called debt deflation.

The only way out of this vicious circle is for the public authorities to intervene consistently, using budgetary and monetary tools. In this situation of debt-induced deflation, public demand must replace private demand to prevent the economy from sinking into recession. With inflation very low, or even negative, the monetary policy of low interest rates loses its effectiveness, as real interest rates

Find out more

Academic references

- Hyman Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, French translation, éditions Les petits matins, 2016

- Irving Fisher, The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions, Econometrica, vol. 4, 1933, p. 337-357

- Gaël Giraud, Antonin Pottier, “Debt deflation versus the liquidity trap: the dilemma of non conventional monetary policy”, Economic Theory, vol.62, 2016

Educational presentations

- Robert Lucas, then President of the Association of American Economists, stated in 2003: ” The central problem of recession prevention is solved, in all its practical implications, and will be for many decades “. The IMF’s April 2006 bulletin (p. 107) describes how financial innovations, and in particular the considerable development of derivatives, have increased the robustness and stability of the global financial system. ↩︎

- Subprime mortgages, granted on a massive scale to US households with low creditworthiness in the years leading up to the 2007-2008 crisis, are an extreme example. ↩︎

- Adair Turner, Taking back control of debt, éditions de l’Atelier, 2017. Translation of the book originally published in 2015. ↩︎

- Assets are tangible “objects” (real estate, precious metals, works of art) or intangible “objects” (financial securities) that have a monetary value for their holder. Assets are characterized by their greater or lesser liquidity, i.e. the greater or lesser ease with which their holders can exchange them for money. Find out more in the fact sheet on the notion of liquidity. ↩︎

- Named after Carlo Ponzi, the most famous swindler of the 1929 Depression era, who left his name to the famous “Ponzi pyramid”: dividend or interest repayments promised to the first subscribers are paid for by the outlays of the next… until the scheme collapses when the cat’s out of the bag, or new subscribers cannot be found. Bernard Madoff set up a Ponzi scheme worth over 60 billion euros. ↩︎

- Irving Fisher, “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions”, Econometrica, vol. 4, 1933, p. 344 ↩︎

- The nominal interest rate is the one actually paid by the borrower. The real interest rate is the nominal rate minus inflation. See explanations on the ECB website. ↩︎