This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Banks are essential economic players, not only because they contribute to financing the economy, but also and above all because they create the money that circulates in the economy. It is therefore essential to understand what is meant by the term “bank” and what their activities are. An analysis of bank balance sheets shows how banking activities have evolved over recent decades. Initially focused on collecting deposits and granting loans to economic agents, banks have increasingly turned their attention to market activities.

What activities do banks carry out?

Banks’ traditional activities include receiving and managing deposits from the public, granting loans and managing means of payment. 1 . The power to grant credit while receiving deposits is linked to the power to create money (see the module on money). A bank must be authorized by the public authorities to operate. In European legal terminology, banks are referred to as “credit institutions”. 2 companies engaged in both activities. In the euro zone, the European Central Bank, in cooperation with the relevant national authorities 3 the European Central Bank, in cooperation with the competent national authorities.

Banks may also engage in financing or market activities, which essentially include issuing securities (stocks and bonds) on behalf of clients (large corporations and governments), market-making (ensuring the liquidity of a security – see our dedicated fact sheet) on the market by acting as a permanent buyer or seller of that security), managing and selling derivatives, and proprietary trading. These activities are referred to as merchant banking or corporate and investment banking.

Historically, the banking sector was highly regulated 4 in most advanced countries, including France. Banks were specialized by customer type and by business line, with a separation between retail or network banks, specialized in collecting deposits and granting loans to individuals and SMEs, and investment banks, specialized in financing operations for large corporations and, later, governments. The banking profession was gradually deregulated in advanced countries. Banking specialization disappeared, and the boundaries between the different business lines became blurred. The sector became increasingly concentrated, leading to the emergence of mega-banks (see our fact sheet on systemic banks), large in terms of balance sheet size, some of which are “universal” in the sense that they carry out retail activities (deposits and loans), market activities and even other businesses such as asset management and insurance.

For these “universal” banks, however, regulations still require the separation of certain financial businesses into specific subsidiaries. The first of these is insurance, which is subject to specific regulations that differ from banking regulations. Secondly, banks have asset management subsidiaries. These subsidiaries invest customers’ savings in investment products (mutual funds, etc.). This activity is also subject to specific regulations. Neither insurance nor asset management are included in the banks’ balance sheets, and are therefore not presented in the balance sheet analyses in this fact sheet.

How to read a bank’s balance sheet

The balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s assets and liabilities at a given point in time (usually the end of the year). On the assets side, we find everything the company owns (how it uses its financial resources), and on the liabilities side, everything it owes (how it obtains its financial resources). Analyzing a bank’s balance sheet enables us to understand what activities it carries out and how it finances itself.

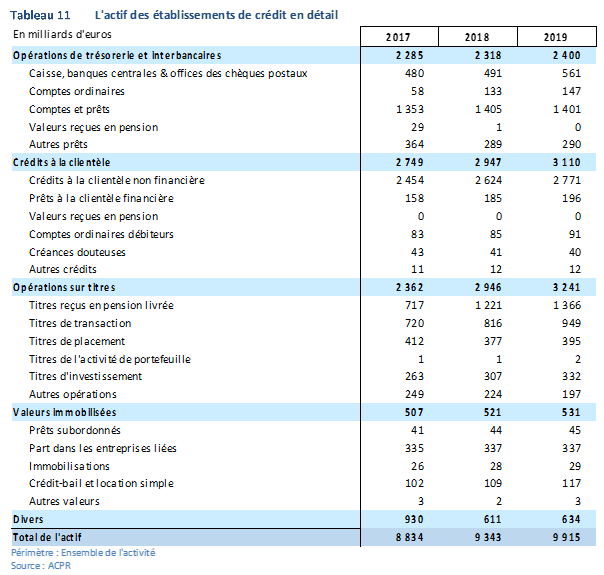

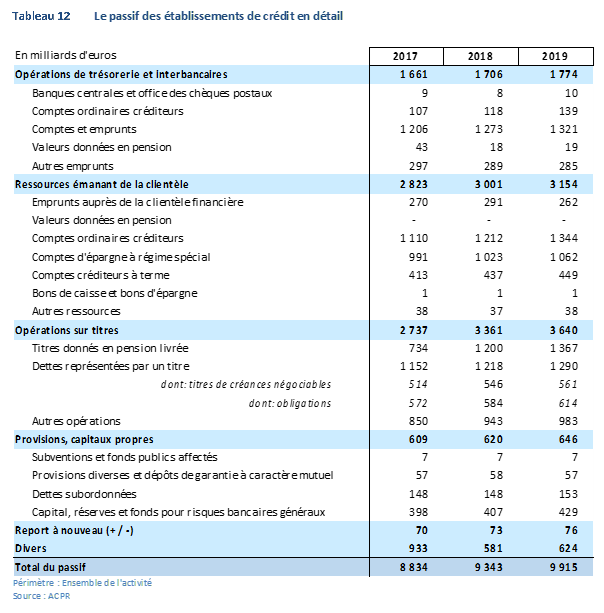

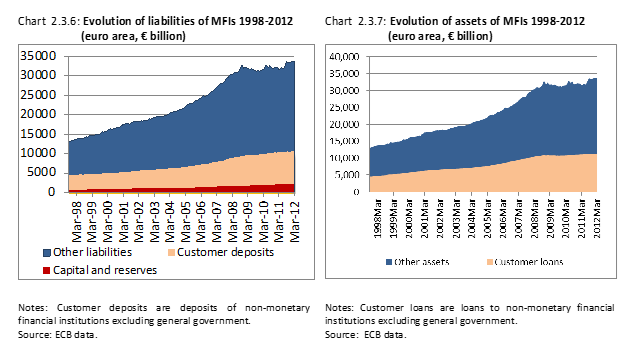

Here are the aggregated balance sheets of all credit institutions established in France 5 .

A detailed report can be found in the appendix.

Source French banking and insurance market figures 2019 (charts 11 and 12), ACPR

What makes up a bank’s balance sheet?

- Class 1 covers interbank transactions carried out by banks with each other and with the central bank, as part of their cash management.

- Class 2 covers transactions with customers (individuals, businesses, local authorities): on the assets side, loans granted; on the liabilities side, deposits collected (current and savings accounts).

- Class 3 covers securities transactions. On the assets side, the bank’s investments on the markets for its own account and its market-making activities. On the liabilities side, debt securities issued by the bank for financing purposes (bonds, negotiable debt securities, securities sold under repurchase agreements).

- Class 4, on the assets side, refers to fixed assets, i.e. goods and values intended to remain with the bank over the long term (e.g. shares in affiliated companies, bank-owned premises, etc.).

- Finally, class 5, on the liabilities side, refers to shareholders’ equity (capital and accumulated reserves, as well as provisions and subordinated debt).

What can we learn from the evolution of bank balance sheets over the last few decades?

The two graphs below show changes in the liabilities and assets of credit institutions based in France since 1993. We can already see the very significant growth in banks’ balance sheets, which have multiplied by 5 in less than 30 years. This reflects the growing role of finance in the economy.

Asset components of credit institutions resident in France (in billions of euros)

MISSING DATAVIZ: composantes-de-lactif-des-institutions-de-credit-residant-en-france-en-milliards-deurosSource French banking market data 2019, ACPR (table G11)

Liability components of credit institutions resident in France (in billions of euros)

MISSING DATAVIZ: composantes-du-passif-des-institutions-de-credit-residant-en-france-en-milliards-deurosSource French banking market data 2019, ACPR (table G11)

If the figures provided by the ACPR 6 start in the 1990s, it is possible to find figures dating back to the 1980s on an educational sheet on the Ministry of the Economy website.

Looking back in time, we can see the extent to which lending to the economy has shrunk as a proportion of banks’ total assets. For French credit institutions as a whole, “traditional” loans to the economy, which accounted for 84% of the sector’s balance sheet assets in 1980, represent just 30% in 2019. 7 . Market activities (securities transactions) and interbank transactions account for 57% of assets in 2019. On the liabilities side, securities and interbank transactions are also on the rise, accounting for almost 55% of liabilities (versus 19% in 1980).

As explained on the Ministry’s website: “This is the consequence of banks’ financing on the financial markets, where they play a major role, either on their own account (direct holding of securities) or on behalf of third parties or as providers of financial products or market makers”. It should be pointed out that proprietary activities are quite simply “speculative” activities aimed solely at boosting bank profits.

It’s also worth noting that, while credit has fallen sharply as a proportion of total banking activity, growth in outstanding credit has nonetheless been very rapid since the 2000s. Between 2000 and 2019, customer credit in France increased by a factor of 2.6, while GDP only grew by a third, and inflation remained below 1.5% a year throughout the period. At the same time, the debt-to-GDP ratio of French households and non-financial companies rose from 83% to 134%. 8 . The financialization of the French economy is therefore reflected in the strong growth of non-credit financial transactions on banks’ balance sheets, but also in the increased use of credit by non-financial players.

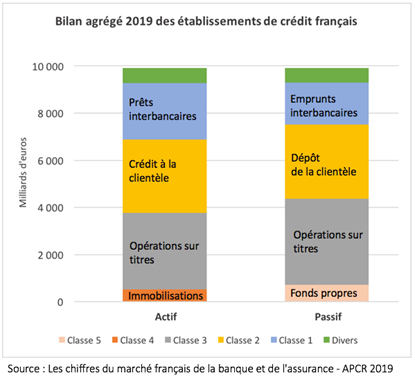

Bank balance sheets reveal the growing financialization of the world economy

According to Adair Turner, who headed the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority at the time of the 2008 crisis[4] :

“If we look at a typical bank balance sheet from the 1960s, we see that apart from holdings of government bonds and cash, it was dominated by household and corporate borrowings and deposits. In Great Britain, loans to the real economy, plus government bonds and reserves at the Bank of England, accounted for over 90% of aggregate bank balance sheets in 1964. By 2008, interbanking accounted for well over half the balance sheets of most of the world’s major banks.““

The same is true of the eurozone, as noted in the Liikanen report.

Source Reforming the structure of the EU banking sector – Liikanen report, 2012 (table A.3.5, p.127)

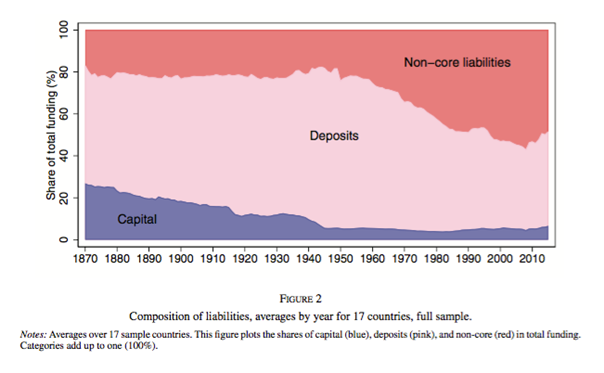

In a recent article published in the Review of Economic Studies 9 the authors trace the evolution of the main balance sheet items for a group of countries over a long period (since 1870). The following graph shows the percentage change in the various liability components of banking institutions in 17 countries. It shows a steady decline in capital and, from the 1970s onwards, a clear reduction in the proportion of deposits in relation to other liability components.

Source Òscar Jordà et al, Bank Capital Redux: Solvency, Liquidity, and Crisis, Review of Economic Studies, 2021.

What about banks’ off-balance sheet items?

Banks’ balance sheets represent only part of their business. Let’s continue to follow what is explained on the Ministry of the Economy website, which defines off-balance sheet banking:

“Off-balance sheet items include items that may result in financial transactions but have not yet been recorded, such as irrevocable credit commitments to be granted, guarantees, purchases and sales of securities not yet recorded to take account of settlement/delivery lead times, and commitments linked to forward financing instruments…”.

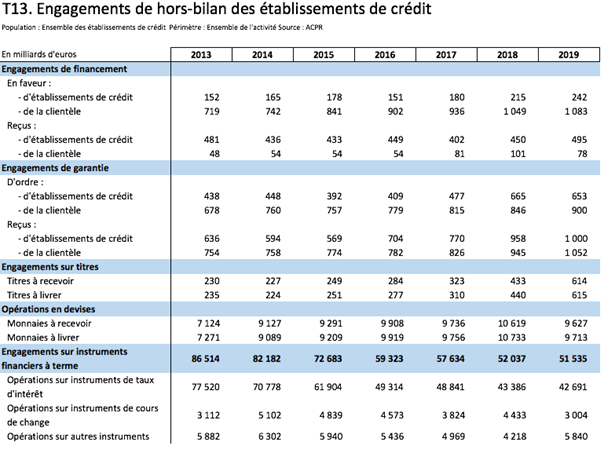

Here are the off-balance sheet figures for French credit institutions in 2019:

Source French banking market data 2019, ACPR (table T13)

The largest off-balance sheet item for banks is commitments on forward financial instruments, i.e. derivative transactions. Despite a slow decline in recent years, commitments on forward financial instruments for all credit institutions still represent over 51,000 billion euros, or more than 5 times the total value of their balance sheet.

Among these derivative commitments, transactions in interest rate instruments are the largest: 42,691 billion euros for 2019. This represents 32.5 times the total amount of loans granted by banks to their customers. This figure is a striking indicator of banks’ activity on the financial markets.

Appendix: Detailed balance sheet of credit institutions resident in France

The tables below are taken from Les chiffres du marché français de la banque et de l’assurance 2019, ACPR.

- Under French law, we refer to “banking operations” as defined by the French Monetary and Financial Code. ↩︎

- A “credit institution” is defined in the CRR (Regulation no. 575/2013 known as the Capital Requirements Regulation – CRR) as “an undertaking whose business is to receive deposits or other repayable funds from the public and to grant credit for its own account” (Article 4). ↩︎

- In France, this is the Autorité de contrôle prudentiel et de résolution (ACPR). ↩︎

- Today, the banking sector remains highly regulated. However, it is no longer the same type of regulation. ↩︎

- These are the corporate data of all legal entities established in France. This includes French credit institutions that are subsidiaries of foreign groups, and foreign branches of French institutions, since they have no legal personality. On the other hand, subsidiaries of French groups established abroad are excluded. For more details see French banking and insurance market figures 2019, banking sector methodological note. ↩︎

- The ACPR is the French public body responsible for supervising the banking and insurance sectors. ↩︎

- The Ministry of the Economy website uses data from 2011-2013. We have updated the figures with the most recent data from French Banking Market Data 2019, APCR (table G11). ↩︎

- See Banque de France website: Household and NFC indebtedness (2020 Q3). Note that the debt ratio of NFCs includes bank loans and bonds, the latter appearing as “securities” in bank assets. ↩︎

- Adair Turner, Reprendre le contrôle de la dette, Edition de l’Atelier, 2017, p.56. For an overview of the evolution of bank balance sheets from the 1960s to 2007, see Adair Turner et al, The Future of Finance: The LSE Report London School of Economics and Political Science, 2010. ↩︎

- Òscar Jordà et al, Bank Capital Redux: Solvency, Liquidity, and Crisis, Review of Economic Studies, 2021. ↩︎