This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Securitization is a financial technique involving the transformation of non-negotiable receivables (real estate loans, consumer loans, car loans, student loans, corporate loans, etc.) into bonds, hence the term “securitization”. As bonds are tradable on the financial markets, investors can acquire them and, in so doing, refinance the banks’ lending activity. This technique, which originated in the USA in the 1980s, is still widely used by financial institutions today. In this factsheet, we explain what securitization is, its mechanisms, its different types, its uses, its players, the role it played in the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and its evolution since then.

The main principles and scope of securitization

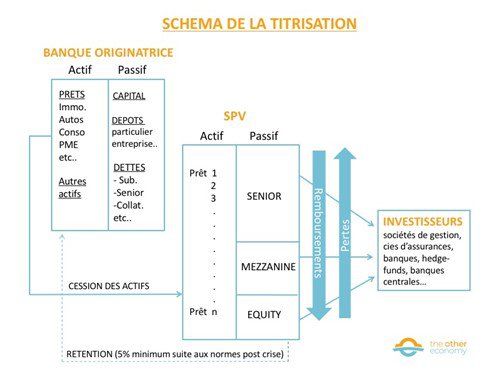

As part of their business, banks grant loans (home loans, consumer loans, car loans, student loans, business loans, etc.) to their customers (households, companies, etc.). To refinance their business, banks have several options, including securitization. Securitization involves a bank (known as the “originating” bank, because it “originated” the original loans) selling a portfolio of loans to a specially-created third-party company, known as a securitization vehicle or, in financial jargon, SPV(Special Purpose Vehicle). To finance this loan portfolio, the SPV issues securities on the financial market, hence the term “securitization”. In effect, the operation transforms a package or portfolio of loans (which are not securities, but loan contracts) into negotiable debt securities, which are purchased by investors or bought on repo by the central bank. Securitization is “collateralized” financing, as the collateral (in this case, the loans) serves as a guarantee and security for investors.

This technique, which originated in the USA in the 1980s under the name of Securitization (a variation of security), developed particularly rapidly from the 1990s onwards, reaching its peak before the 2007-2008 crisis. It is still widely used today, particularly in the United States, where a large proportion of loans to companies

Find out more

Securitization statistics in the United States

Securitization statistics in Europe

The securitization mechanism in detail

The originating bank sells the loan portfolios it has granted to its customers to a finance company.

The originating bank transfers a portfolio of loans it has granted to its customers to a third-party company specially created for the purpose. This company is known as a securitization vehicle or, in financial jargon, an SPV ( Special Purpose Vehicle). This real and effective transfer of loans is called a true sale.

The number of lines making up the loan portfolio transferred to the SPV varies widely, depending on the type of collateral. It can range from a few dozen lines (corporate loans) to several thousand (housing loans). By transferring loans to the SPV, the bank also transfers the associated risks (with the exception of regulatory retention – see paragraph 3), in this case non-payment by borrowers of all or part of the interest or nominal amount (i.e. outstanding capital).

It should be noted that this loan transfer operation is transparent for the originating bank’s customers. When the bank grants the loan, it receives a commission. Borrowers then regularly repay the principal and pay interest, as in a non-securitized loan. The difference lies in the fact that the bank passes on this interest and the principal repaid to the SPV. The bank’s relationship with its customers is therefore unaffected by securitization.

It should be noted that securitization entails substantial costs (creation of an SPV, arrangement and placement fees, securitization swap, etc.) paid by the originating bank to one or more banks that arrange the transaction. This is known as the arranging bank. The larger the vehicle, the more these costs are amortized.

The SPV finances the loan portfolio acquired from the originating bank by issuing bonds with varying degrees of risk.

The SPV is a company whose sole corporate purpose is to refinance the loans assigned to it by the originating bank. As the SPV has no resources of its own, as soon as it capitalizes the loans on its balance sheet, it must finance itself. To do this, it issues bonds on the financial market, which are purchased by investors.

When the transaction is set up, the SPV must inform investors of the composition of the portfolio and provide details (amount, rate, maturity, etc.) on each of the lines(Investor Pool Data Pack), with the exception of the customer’s name, which is anonymized by virtue of banking secrecy. Investors thus have a precise view of all the financial flows that the SPV will receive throughout its lifetime, which is (to simplify) equal to the lifetime of the portfolio.

Investors therefore bear the risk of loan default. They have no recourse against the originating bank, since they have purchased the securities in full transparency. This is the principle of Non Recourse Financing.

To finance the entire portfolio of loans purchased from the originating bank, the SPV issues different types of bonds (Senior/Mezzanine/Equity), known as tranches 1 . Each tranche carries a different risk, so investors are affected differently depending on whether they own one or another. So, if one or more borrowers default, the losses will first be borne by investors in the “lowest” tranches (also known as the “most junior” tranches, the most junior of all being Equity), then when one of them is fully impacted, it’s up to the “top” tranche (which is therefore more senior, and which may be the mezzanine tranche if issued, or the senior tranche) to be affected in turn, and so on.

Investors are also reimbursed for their initial investment according to their rank (known as seniority rank). In effect, the amortization of securities (on the liabilities side of the SPV) follows the amortization of loans (on the assets side of the SPV). So, as the loans are repaid, the nominal value of the various liability tranches decreases ( Pass-Thru principle). The most senior tranches are repaid first, and so on until the loan portfolio is fully amortized. This cascading mechanism is known as Waterfall.

Apart from the very specific case of so-called short-term securitization (ABCP – Asset Backed Commercial Paper – see below), which is marginal, there is no transformation, i.e. financing of long-term assets (loans) by short-term resources.

The senior tranche is therefore the least risky, since it is protected by the junior tranche(s), and is repaid first. For these reasons, it generally obtains a (very) good rating from the rating agencies (Standard & Poors, Moody’s, Fitch…).

As each tranche has different associated risks, the interest rate that remunerates the holders of these tranches, i.e. the investors, is different. The riskier the tranche, the higher the return to the investor, and vice versa. The terms of remuneration on each tranche are determined by market conditions at the time of the transaction (supply and demand for each of the securities in question).

While the investors are varied (fund managers, hedge funds, bank treasuries, central banks, etc.), the regulations introduced since the 2008 crisis require that they all be securitization professionals, and that this be explicitly stipulated in their mandate.

The different types of securitization

In theory, securitization can be used to securitize any type of loan or receivable (receivables, Dailly receivables, etc.). In reality, there is a market consensus that the originating bank can only securitize certain types of loans (or collateral), which correspond to a specific terminology. Each type of collateral corresponds to a securitization type, which can be classified into two main categories:

1/ ABS stands for Asset Backed Security (asset-backed security)

- RMBS or Residential Mortgage Backed Security: real estate loans

- (ABS) Auto loans/leases: car loans or leases

- (ABS) Consumer loans: consumer loans

- (ABS) Credit Card: credit cards

2/ CDOs stand for Colleralized Debt Obligation (bond collateralized by debt)

- CLO for Collateralized Loan Obligation: loans to companies (usually small or medium-sized).

- CSO for Collateralized Synthetic Obligation: loans to (usually large) companies

In this case, the bank retains the assets but transfers the credit risk and the remuneration of the credit to the vehicle via a synthetic contract. This is known as synthetic securitization.

Whatever the type of securitization, it always involves the SPV issuing security bonds, backed by collateral. Each bond has a different risk/return profile.

Another category is short-term securitization, in which ABCP(Asset Backed Commercial Paper) is issued. This involves financing assets by issuing short-term securities (or papers) with maturities ranging from 10 days to 1 year. This type of securitization presents a transformation risk, since the assets (trade receivables, etc.) are potentially longer-term than the securities issued. This transformation risk is ultimately borne by the originating bank. The amount of this type of transaction is fairly marginal compared with long-term securitizations.

What is the advantage of securitization for banks?

- Refinancing

Securitization enables banks to refinance their activities, and in particular to diversify their sources of refinancing (known as the funding mix), sometimes at lower cost.

When they grant loans, banks create money: on the assets side, they record the borrower’s claim, and on the liabilities side, they credit the borrower’s deposit account with the same amount (see money module). However, as the borrower may use this money to pay someone whose account is held at another bank, the banks need to refinance. To do this, they can either borrow (from the central bank or other banks), issue bonds on the financial markets, or securitize assets (loans), thereby reducing their refinancing needs.

- Regulatory capital release

Prudential regulations, stemming from the Basel agreements, require banks to hold a certain amount of capital corresponding to a percentage of their assets, including the loans they grant. 2 . The aim is to ensure that banks are able to absorb losses caused by borrower default (or by the devaluation of other assets).

The situation before the global financial crisis

Securitization enables the bank to free its balance sheet of loans that are a burden on prudential ratios. The bank received commissions when the loan was initially granted. Subsequently, it no longer receives the interest on the loan (since it passes it on to the SPV), but neither does it bear the capital charge imposed by these ratios. It can therefore use its regulatory capital to carry out new credit operations, which it then sells to the SPVs, and so on, to generate more commissions with the same capital charge. This is what some American banks did before the crisis with their sub-prime loans (see below).

Over and above this effect on the release of regulatory capital, securitization means that the bank no longer bears the risk of borrower default: it passes it on to the investor who acquires the SPV’s securities. As a result, the bank may be encouraged to grant loans without serious risk analysis, or even to encourage risky lending. This is typically what happened with the “subprime” loans at the root of the 2008 financial crisis (see below).

Regulatory developments since the crisis

Following the 2007-2008 crisis, the regulatory authorities imposed a number of rules, including the obligation for the originating bank to retain at least 5% of the risks of the loans it has granted, in order to improve the alignment of interests between originating bank and investors. The most common method is for banks to take over the most junior tranches (equity, etc.), since these are the riskiest. In general, they retain much more risk (12 to 20% of the SPV’s liabilities, sometimes more). Another method is for the originating bank to take over 5% of each tranche (Equity, Senior, Mezzanine if any).

When the originating banks create an SPV and sell the senior tranches to investors, while retaining the equity tranche, this does not reduce their regulatory capital charges, since they retain virtually all the portfolio risk. Today, this is generally the case in Europe (over 95% of cases).

Conversely, if the bank sells the Equity tranche of the SPV (with the exception of 5% of the nominal value of this tranche for retention), it can release regulatory capital.

This type of operation, known as Reg Cap (for Regulatory Capital), is marginal. It is mainly used to free up regulatory capital in the capital-intensive corporate lending business.

Depending on the type of operation, investors are very different. Indeed, as we have seen, banks are regulated: they must have regulatory capital in front of each of their investments. This is also the case for insurance companies. If a bank or insurance company acquires securities issued by an SPV, its capital requirement will increase: the riskier the tranche, the higher the regulatory capital requirement.

Thus, the most senior tranches are generally purchased by management companies acting on behalf of insurance companies, bank treasuries or central banks. The most junior tranches, whose Equity (when it comes to market), are generally purchased by hedge funds, which are not regulated and therefore not subject to regulatory capital requirements.

The role of securitization in the 2008 financial crisis

Prior to the 2007-2008 crisis and the regulatory changes that followed, lending institutions were not obliged to retain part of their portfolio. Since they no longer bore the risk of default by the original borrower (household, company, etc.), certain financial players (generally small banks or speciality lenders), particularly in the United States and Great Britain, were encouraged to grant loans without any serious risk analysis, since they then sold them on to others for a commission. Subprime loans were real estate loans granted to low-income American households with insufficient collateral to qualify for a normal “prime” loan, either because their income was low or uncertain (precarious contracts, etc.), or because they had already experienced financial difficulties in the past. The characteristics of subprime loans were also unconventional (deferred repayment, etc.).

Securitization led to this type of risk being redistributed to investors all over the world. These investors were not always aware of the risks involved, especially as the rating agencies gave good marks to these transactions, or at least to some of the tranches. As the financial ecosystem became more industrialized and complex, these risks spread to all players who were not involved in subprime lending, such as investors in continental Europe.

Low interest rates on both sides of the Atlantic had also led to the emergence of bubbles in a large number of assets (real estate, financials, etc.). Not only were borrowers forced to borrow more and more, but American and European investors (management companies, banks, etc.) were also led to buy increasingly complex and risky products in order to earn attractive returns.

What’s more, there was an industrial ecosystem of recycling techniques, such as securitization of ABS (CDOs) and SIVs(Structured Investment Vehicles), which buried this type of risky security in other financial products, making it very difficult to track portfolio trends and, consequently, security valuations.

Also, when the FED, the US central bank, raised rates for fear of overheating and the US economy slowed down, this led to defaults on subprime loans, which had a multiplied impact given the global spread of these risks and the associated financial leverage effects.

The valuations of sub-prime securitizations plummeted, causing the values of other assets – even good-quality ones – to plummet, as some investors were forced to sell them to meet the repayment demands of panicked end-customers. A vicious circle was set in motion, triggering a chain reaction similar to panic selling. With investors, including banks, unaware of what they had in their portfolios, let alone what others had, confidence in the financial system, particularly the banking system, was shaken. This lack of confidence in lending led to the collapse of the most fragile financial institutions (Lehman Brothers, Bear Stearn…), which in turn triggered other chain reactions in the banking world due to the interconnection of financial players, with the result that the real economy seized up.

The world’s central banks had to be called in to stem the panic, but the damage was done. The financial crisis of 2007-2008, which originated in the United States, affected investors the world over and spread to the productive economy, triggering a collapse in activity, mass unemployment and social crises across the globe.

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 highlighted the fact that the financial world was interconnected and needed to be made both more resilient and more virtuous by introducing regulatory safeguards.

Because securitization made it possible to recycle all types of assets, including some of poor quality, such as subprime mortgages, it also allowed many abuses.

In the spotlight, securitization has been the subject of a large number of regulatory changes (Retention Rule, Standard STS, Mifid II, etc.), bringing it much more into line with its initial objective of helping to finance banks’ activities, and even freeing up capital. The current danger lies less in its ability to recycle low-quality assets than in the fact that it is helping to create asset bubbles inherent in the Quantitave Easing implemented by central banks, with no real counterpart in terms of financing the economy or even the banks’ commitment to financing environmentally sustainable activities.

However, the financial ecosystem (institutional investors, central banks, etc.) is structured in such a way that securitization could be an immediately effective tool for (re)financing activities in line with sustainable development objectives. This would only require that the assets transferred by the originating bank to the SPV be qualified as such (renovation loans, business transition loans, etc.), particularly in terms of the European taxonomy (currently being drafted).

- In securitization, there are at least two tranches (Senior and Equity), but it is not uncommon for SPVs to issue 7 tranches (this is generally the case for CLOs – see below). ↩︎

- The solvency ratio, a central tool of prudential regulation, requires banks to hold a percentage of risk-weighted assets as capital. But there are other ratios as well, such as the leverage ratio and liquidity ratios. See sheet on prudential regulation. ↩︎