This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Capitalism is sometimes presented as the main cause of the current ecological and social crisis. 1 . For some, it should be renamed capitalocene 2 what geologists call the Anthropocene. 3 For others, we need to get out of capitalism to resolve this major crisis. There’s no denying that the current “capitalist” economic system, now dominant on the vast majority of the planet, is to blame. 4

However, it’s not so easy to define capitalism even if we limit ourselves to the economic level, nor to clearly identify what needs to be abandoned from this system and what needs to be put in place to save humanity from the current shipwreck. It’s only through analytical work, barely sketched out here, that it’s possible to know whether we should “throw everything” into capitalism, or rather transform it, possibly in depth.

The long-standing debate between three options (maintaining the “model”, rejecting it or reforming it in a “social-democratic” or now “social-ecological ” way) needs to be revisited from this perspective. In conclusion, we will outline a few avenues for transforming our economic system.

Capitalism as an economic system: an attempt at definition

The term capitalism, which first appeared in the mid-18th century, is not easy to define. 5 both because its definition explicitly or implicitly refers to fundamental disputes, and because it is multiform: it would be more rigorous to speak of capitalisms. 6

In this fact sheet, we won’t venture into the sociological, political and historical terrain of Karl Marx and his successors. In a nutshell, Marx’s definition and analysis of capital and capitalism focused on the relations of domination between social classes, with the capital-owning bourgeoisie exploiting the wage-earning class. Not addressing these issues here does not mean that they are of secondary importance, nor does it mean that in our view the economy can be “disengaged” from the institutions that frame it and the relations of power. It is clear that the capitalist system was built and continues to evolve as a result of these movements.

An attempt to define capitalism

In economic terms, capitalism can be defined as a system in which one party (usually a majority, but this share can vary greatly 6 ) of the means of production is owned by companies with private financial capital.

These companies own machines, equipment, buildings, stocks, etc. They use subordinate labor, mainly salaried employees since the 19th century. 7 They buy what they need to produce and sell goods and services. Finally, they use “resources” or “natural capital”, without accounting for them. 8

Decision-making power in these companies – including with regard to distributed income 9 – is given to the holders of this capital, who, a priori, will look after their own interests, which are primarily to accumulate more financial capital (we’ll come back to this point later). In some countries, this power is attenuated by the presence of employee representatives on the highest decision-making bodies (boards of directors or supervisory boards). 10

There’s obviously a difference between small bosses, whose strength lies mainly in their own work, and financial shareholders (or wealthy individuals) whose power derives solely from the ownership of capital. The adjective “capitalist” is more apt to describe such people than “small businessmen”.

Within so-called “developed” economic systems, capitalism is distinguished from collectivism, in which the means of production belong to the state. According to this definition, the Chinese economy has gradually become capitalist. 11 since the reforms launched by Den Xiaoping in 1978.

Capitalism has many variants

These variants depend on a number of factors:

- the way in which the rights attached to ownership of a company’s financial capital and those granted to other stakeholders 12 are defined in company management (for example, “Rhenish capitalism” is characterized by co-determination 13 between employees and shareholders);

- the relative weight of the public sector in services, insurance and social transfers (rather high in France and Northern European countries, lower in Anglo-Saxon countries);

- the relative weight of the associative sector and, more generally, of the social economy (including mutuals);

- the role of political power over the economy (obviously omnipresent in China).

- the role of financial power (stronger in the Anglo-Saxon world, and which has grown considerably over the past 40 years in the West, as we show in the module on the role and limits of finance).

Capitalism is inseparable from the market economy

The market economy is an economic system based on the decentralization of decisions concerning the setting of prices and the production and exchange of services and goods.

Throughout history, there have been non-capitalist or pre-capitalist market economies, such as the European societies of the Middle Ages. Today, one cannot exist without the other. It can therefore be said that one of the essential characteristics of capitalism is that decisions concerning the prices of traded goods and services are not taken by a centralized planning body, but by economic players (more or less concentrated depending on the case). The aim of this fact sheet is to discuss the advantages and limitations of capitalism in a market economy.

Capitalism has evolved over time and in different countries around the world.

It is possible to distinguish five broad periods in the West:

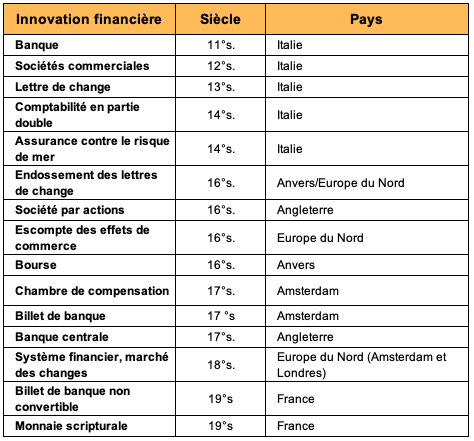

- From its birth (see box) in Italy in the 14th century to the Industrial Revolution in England at the end of the 19th century: these were the beginnings of capitalism. It was during this period that capitalism was defined and built.

14

legal instruments relating to property, the “labor market” and the land market were progressively defined and constructed.

15

accounting, competition, money, financing mechanisms and the institutions needed to operate them (banks, stock exchanges, regulators, etc.);

- From the end of the 19th century to the crisis of 1929, this was the classical, ideologically liberal period. The economy was supposed to regulate itself spontaneously, and the state was not to intervene either socially or politically.

16

The state should not intervene either on the social level, or to deal with crises (which allowed the “dead wood” to fall off, i.e. unprofitable or weak companies). This is the idea of “laissez-faire, laissez-passer”. 17

- From the 1929 crisis to the 1970s, the period was Keynesian and dirigiste.

18

Capitalism became “social-democratic”, with the generalization of the welfare state.

19

Roosevelt, President of the United States after the Great Depression, was the political embodiment of this new conception of the economy. He did not hesitate to limit the power of finance and launch major social programs, notably in response to the 1929 crisis, which also had an ecological dimension, with the

Dust Bowl

. However, Nature was largely forgotten in this period, as in the next.

- Since the end of the Bretton-Woods agreements

20

in the early 1970s, capitalism has become “neo-liberal”.

21

globalized and financialized. The state must be at the service of business. The “free play” of markets is supposed to lead to an economic optimum (as in the first economic period, but this time on a global scale). As we show in the module on finance, this period was marked by the liberalization of capital markets, the deregulation of banking activities and the decline in the power of public authorities (who lost control of the monetary instrument, and were forced to finance their deficits on the markets in order to submit to the healthy discipline of the markets). Another characteristic feature is the promotion of world trade and free trade at all costs. This ideology, which permeates the construction of the European Union, accords a fundamental place to the four freedoms of movement (of people, goods, services and capital).

- Since the financial crisis of 2008-2009, there has been a slowdown in globalization and free-trade ideas. The COVID crisis, and even more recently Russia’s war in Ukraine, seem to be closing this period, with a renewed focus on industrial policies and sovereignty issues.

When was capitalism born?

There is a debate about the “birth” of capitalism, linked to its definition. Some authors see capitalism as being born with the Industrial Revolution. For others, like the economist and historian Werner Sombart, the Industrial Revolution began in the 14th century with the emergence of “bourgeois civilization” and “entrepreneurship” in Florence. For Fernand Braudel, capitalism is a “civilization” with ancient roots, whose prestigious heyday is attested by the influence of the great merchant city-states of Venice, Antwerp, Genoa, Amsterdam, etc., but whose activities remained in the minority until the 18th century. Here, we emphasize the idea of a gradual overall movement that began with the creation of the joint-stock company in the 14th century, and accounting, which made it possible to precisely measure the enrichment of shareholders.

Source See Jacques Richard and Alexandre Rambaud. Révolution comptable – Pour une entreprise écologique et sociale, Éditions de l’Atelier, 2020. See also Maxime Izoulet’s thesis, Théorie comptable de la monnaie et de la finance, EHESS, 2020.

The role of capital accumulation in the dynamics of capitalism

For Karl Marx and his successors, the driving force behind capitalism is the accumulation of capital (in the sense of money invested with a view to its “fructification”). Producing commodities is merely a detour to this end.

This view is somewhat simplistic: many capitalists are first and foremost entrepreneurs, even visionaries, driven by a “mission”. For them, capital is a means to an end, not an end in itself, even if some of them are also or become owners of capital, or even build “dynasties” of their own.

But it is undeniable that the dynamics of capitalism are linked to the fact that capitalists devote their energy and skills to making their financial capital bear fruit, either in industrial ventures or in financial operations.

This desire for fructification, which needs the accounting to measure and manage it 22 is undoubtedly linked to the capitalist’s thirst for enrichment. 23 It was gradually freed from religious and moral constraints in the Middle Ages, when theological debates on the “lawfulness” of profit and interest (in the sense of interest-bearing loans) were intense. 24 Bernard Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees can be seen as the first turning point in this emancipation.

Financialized capitalism

After the financial liberalization of the 1970s and 80s, an even more uninhibited form of capitalism was born, in which the unlimited enrichment of corporate executives is justified by the “value” created for shareholders.

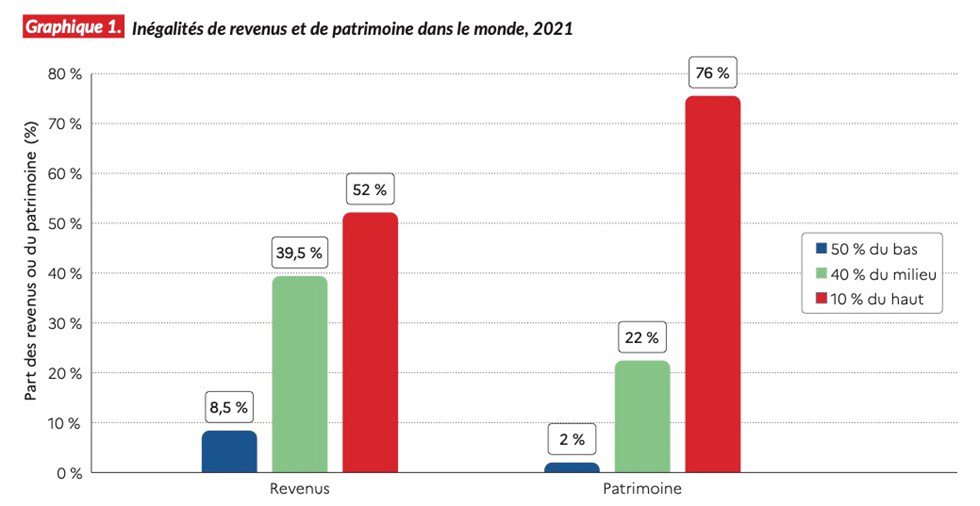

This is how huge fortunes were built. In 2021, according to the World Inequality Lab, the wealthiest 10% of the world’s population will own over 75% of the world’s wealth. Conversely, the poorest 50% (3.8 billion people) will own just 2% of the world’s wealth.

Income and wealth inequality in the world in 2021

Source World Inequality Report 2022, World Inequality Lab.

This neo-liberal, financial and globalized capitalism, the latest incarnation of capitalism, is much more unequal than its predecessors. 25 than the capitalism of the Keynesian period (see above), creating a global balance of power unfavorable to workers and wage earners. 26 through so-called “free and undistorted” competition 27 a generalized opening-up of international trade (in goods, capital and services) and an uninterrupted process of mechanization/automation/computerization/robotization, which puts workers under permanent pressure.

It demands higher returns on the capital invested in companies, and thus shortens the horizons of business leaders (starting with listed multinationals, which impose this short-termism on their suppliers, subcontractors and, in turn, on all companies). In fact, the quest for high returns translates into the discounting of financial flows at high rates, which reduces the weight of distant financial flows, and therefore the weight of the future in economic decision-making. It’s an iron law. 28 This short-termism (and the short-termism shown by politicians in today’s democracies) is at the root of the “tragedy of horizons” highlighted by Mark Carney, which makes the fight against climate change so desperate.

It is one of the powerful gas pedals of the ecological crisis as a whole, the effects of which are distant and unaccounted for in corporate management accounts, as we explain in the module on corporate accounting.

What is the tragedy of horizons?

In September 2015, in a speech delivered at Lloyd’s headquarters, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, asserts that global warming presents risks with potentially systemic financial consequences. He introduces the concept of the “tragedy of horizons”. The gap between the short-term horizons of financial players and the long-term horizons of climate impacts means that financial players are unable to identify the risks they run as a result of global warming.

Find out more in the section of the Finance module devoted to systemic climate-related financial risks.

What’s in it for the company?

The central issue in current discussions about capitalism revolves around this question: what should be the purpose of the company and the motivation of shareholders and the managers they appoint?

Does it have to be purely financial? The “law of profit 29 the main compass for decision-making?

In other words, the question facing capitalism today is whether it is possible to reconcile the irreconcilable, the subject of a “theological” debate already mentioned. 24 which ran through the Middle Ages in Europe, and which is based on this famous “aphorism”: “No one can serve two masters: either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will cling to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and Money”. (Gospel of Matthew, 6, 24-34)

As mentioned in the introduction, there are three opposing theses:

1/ For Milton Friedman, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, there is no doubt:

“There is one and only one responsibility of business: to use its resources and commit them to activities designed to increase its profit.” ( The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits , 1970)

Let’s also quote these trenchant words from economist Branko Milanovic, a specialist in social inequalities:

“If the dominance of the capitalist mode of production is unchallenged, so is the ideology that making money is not only respectable, but also the most important goal in people’s lives (…) We live in a world where everyone follows the same rules, speaks the same language of the quest for profit”.(Le capitalisme sans rival, 2020, p.19)

2/ Should we instead bring other stakeholders, including Nature (according to specific modalities to be defined, of course, as Nature is not a legal entity), “at the table of the decision?

If so, can we ensure that capitalists pay as much attention to natural and human capital as they do to financial capital? How can we ensure that the “law of profit” doesn’t reduce the interests of other stakeholders to the bare minimum, despite “good intentions” and “fine words” to the contrary?

3/ Last option: should we “capitalism”? ?

This option is often mentioned, without its exact meaning being specified. Does it mean nationalizing all companies (even small ones)? Capping capital gains? In-depth changes to the rules of governance, for example, by extending the co-determination of decisions, or by generalizing the associative model? 30 Depending on the version envisaged, this exit may be confused with the previous option.

Before giving our answer, let’s take a detour into the contributions of capitalism and the market economy.

The contributions of capitalism and the market economy

Capitalism has had many positive and negative effects. Let’s start with the positive.

It has enabled the emergence of know-how, social organizations and technologies beneficial to human societies. The massive increase in productivity in just a few centuries has put an end to the inevitability of famine for the majority of human beings. 31 It has freed some of them from the physical effort required to survive.

Capitalism lifted Europeans out of poverty and, from the end of the 20th century onwards, many Chinese… 32 although this is not to be attributed to neoliberalism, as Chinese capitalism is very different. Let’s take a closer look at the “virtues” of capitalism.

It helps to have motivated, focused “entrepreneurs 33 on precisely-defined activities that best satisfy their customers

Entrepreneurs seek to satisfy a need or desire (present or future, solvent or potentially solvent) by developing, producing and selling a product or service.

They have several functions: raising financial capital, launching and managing their business and its projects, ensuring that it is profitable or will become so, hiring, organizing work, innovating and stimulating innovation, finding customers, suppliers, service providers, bankers, possibly associates, partners… All this while respecting the constraints imposed by the legislator, and benefiting, in return, from the “means” made available by society (educated, trained and healthy staff, legal system, energy, transport and communication infrastructures, security, etc.).).

To embark on and pursue such an “adventure”, the entrepreneur needs to be motivated. In general, there are several types of motivation:

- he feels at home (he doesn’t obey a boss) and free;

- he hopes to earn money commensurate with the risks (financial, moral, legal…) taken, the energy expended and the results obtained;

- In some cases, he wants to have an impact on the world, sometimes to bring about or even impose a certain vision of it.

The “alignment” of these different motivations is a quality of capitalism. It ensures that financial recognition is consistent with symbolic recognition.

It’s useful to have mechanisms for decentralizing exchanges

The “market” is the institution that makes this decentralization possible. Every day, billions of products and services are exchanged between billions of people around the world. There are two advantages to using a decentralized price whenever possible:

- An interest in distribution: production is de facto distributed via purchases; in this case, distribution is decentralized, not decided by a central authority. This maximizes economic freedom;

- An interest in the efficiency of the production process: when prices are fixed on a competitive market, the buyer exerts pressure on the producer to adapt to his wishes, lower his prices and generally his costs; this encourages him to make productivity gains. The “producer” (farmer, industrialist, service company) knows, can know, or at least has information about his customers’ needs, their willingness to pay, his own costs and their structure (fixed costs, variable costs), as well as his production methods. It can therefore act to improve the service it provides to its customers, innovate, produce differently, etc.

Financial innovation within capitalism has several benefits

The development of capitalism has been accompanied by numerous financial innovations (see box and, for more recent examples, the sheets on derivatives and securitization ). These innovations have made it possible, among other things, to provide “dematerialized” money, to mobilize the savings of some to finance the projects of others, and to develop methods and systems for managing risks of all kinds.

The birth of capitalism is linked to that of the great voyages organized by the masters of Italian cities. Pierre-Noël Giraud’s remarkable book 34 the importance of financial innovation in these great commercial expeditions. The detailed distribution of responsibilities, risks and rewards was an essential skill in the face of human initiative and creativity.

In the same way, the art of collecting savings from some, and knowing how to assess the credit risks of others, enables, if not an optimal allocation of capital, at least its “recycling” and potentially socially useful money transfers.

Business law is highly inventive and highly adaptable to the multiple configurations of interests of the parties involved in a project.

Since capitalism places the interests of economic players at the heart of its “agenda”, it takes great care and creativity to ensure that this is the case: contract law, and more generally business law, is immense and can deal with many original situations. All this enables “stakeholders” to assert their interests in a detailed manner, which contributes to the first of capitalism’s assets that we highlighted above. Paradoxically, it is within capitalism that different types of company status have also developed, and structures are possible in the world of the social economy (cooperatives, mutual societies, foundations, etc.). Capitalism can therefore take on interests that are not strictly financial.

Why do these mechanisms need to be supplemented and regulated?

While capitalism, driven by the lure of money, has had positive effects and intrinsic qualities, as we have just seen, it leads to excesses that can become intolerable. Capitalist dynamics have been accompanied by considerable pressure on colonized populations, workers and planetary resources.

Crossing planetary boundaries 35 is still not a problem for some capitalists, who are driven by a sense of omnipotence (“technology will save us”) and, beyond money, by the desire to surpass all limits, as demonstrated by transhumanist ideology.

The fact that monetary capital can grow without limit (money has become entirely dematerialized, being created ex nihilo, as we show in the module on money) is obviously not unrelated to this lack of restraint.

As Marx saw, capital gives capitalists considerable power not only over wage-earners, but also over Nature.

Regardless of these excesses, capitalism needs to be regulated for clearly identified reasons. Let’s look at the main ones.

Public infrastructures and facilities are needed for knowledge creation and acquisition

A company is not born and bred out of the ground. It needs :

- natural resources (a habitable planet with a breathable atmosphere, an acceptable climate, materials, energy and water used in all processes…);

- sufficiently educated and trained workers who can integrate socially into the company;

- public (i.e. financed by redistribution systems based on various compulsory levies) or private “external” services: security, a healthcare system, a right that can be respected (because it is fairly well constructed and the mechanisms for enforcing it are fairly effective), roads and other logistical resources, communication networks and so on.

- available knowledge and know-how, and therefore industrial or service ecosystems, as well as research that works;

- a sufficiently stable society, where there is a minimum of trust between people and institutions.

This last point (the need for a fairly stable society) is open to debate: it is possible to make a fortune during a war (which enriches arms manufacturers, black-market “débrouillards”, etc.). The extension of lawless zones can contribute to the arrival of a “strong” power that can allow business to develop; we know of examples of countries with very high levels of social injustice where business “works” well.

On the whole, these arguments are short-sighted. Alain Peyrefitte, in his book La société de confiance, shows just how useful this value (trust) is for business and its development. There’s no need to demonstrate that generalized mistrust (born of a noxious climate) complicates and slows down everything. 36

Clearly, all or part of the services and infrastructures described above must be public. 37 Companies need them in the country where they operate, and are generally not attracted to countries where these services are lacking. On the other hand, the private sector cannot provide many of these services because they are not, or not sufficiently, profitable. 38 without government intervention.

Common” management systems are needed at various scales

The natural commons

From watercourses to the climate, business depends on common goods. Their deterioration (through pollution, for example) and/or over-exploitation can “benefit” some (in the sense that they can be a source of income) and harm all.

This risk is intrinsic to the spontaneous functioning of the free market. Nature doesn’t get paid for the services it provides, nor for the damage we do to it. Within the free functioning of the market, and in corporate accounts, Nature is not counted.

It is only felt through its “physical”, “concrete” effects. Economists speak of externalities precisely because these effects are not directly monetary, and are therefore considered external to the economic system. 39

It is therefore up to the public authorities to ensure that these effects are taken into account by economic players, so that they can prevent, limit or mitigate them. In some cases, public authorities must make these effects impossible. It can do this by various means (prohibitions, regulations, taxation, etc.).

Accounting can be thoroughly reformed in this direction, leading to a redefinition of “profit” that would integrate these “externalities” into its construction.

Generally speaking, these commons cannot be managed efficiently by privatizing them. 40 and not necessarily by “nationalizing” them. Again, history teaches us this: during the (economically) communist periods in Russia and China, local pollution could be severe.

In the majority of cases, it is desirable to develop hybrid arrangements, involving the various stakeholders, particularly local ones, whose interests are most directly linked to the preservation of this common good. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDI) is an emblematic example of this hybrid format. 41

When it comes to national or international common features, the French government is the only player with the legitimacy to create or promote these systems, and the only one with the necessary fiscal and budgetary tools.

The currency

Currency is an indispensable institution in modern market economies, both within and between countries. Created from a simple set of bookkeeping entries, it must be subject to strict regulations. In particular, the management of monetary policy (including the “lender of last resort” function), crucial to the rule of law, is necessarily public.

Find out more in our Money module.

The “commons of the mind

Ideas, scientific theories, language and its words cannot be privatized, since they belong not to the person who first discovers or patents them, but to everyone, forever.

We need systems that prevent the creation of a caste of rentiers and limit social inequalities.

“Money goes to money”, “the winner takes all”, etc. These empirical observations have been demonstrated mathematically by Nicolas Bouleau and Christophe Chorro. 42 Thomas Piketty has popularized an obvious arithmetic fact: if the return on wealth is higher than the growth rate of the economy (i.e., higher than that of average income), the richest of the “rentiers” (wealth holders) will eventually become hyper-rich, by virtue of the exponential property: a growth rate greater than 1 causes wealth to grow very rapidly (see the “exponential property” box in the module on natural resources).

In this case, capitalism becomes caste capitalism. The rentiers are not (with a few exceptions) entrepreneurs, but conservatives, and their only aim is to preserve their privileges.

As far as social inequalities are concerned, their level of acceptance in a society depends on numerous sociological, cultural, anthropological and historical factors…

In economic terms, efficiency is not independent of equity (contrary to popular belief). 43 ) For example, Tancrède Voituriez and his co-authors:

“IMF and OECD studies show that rising inequality is unsustainable from a strictly economic point of view, insofar as it acts as a brake on growth.” 44

On the other hand, exceeding the “tolerable level” can lead to situations of social disorder, or even more, which are generally undesirable. There is no reason why the market should spontaneously avoid exceeding this level. The public authorities therefore need to get involved through appropriate measures, such as income caps. 45 a highly redistributive tax system on income, capital and inheritance. 46

Market regulation mechanisms are needed

The creation of monopolies

The “theorems” that claim to demonstrate that a free-market economy equilibrates spontaneously and leads to an economic optimum are based on the hypothesis of diminishing returns. 47 rarely encountered in “real life”.

When returns are increasing, the formation of monopolies and the risk of abuse of dominant positions are inevitable, without public intervention. Such monopolies are sometimes desirable: this is clearly the case with rail, electricity and digital networks, which are “natural monopolies”. 48

In other cases, they clearly aren’t: think of banks and non-bank financial players, the Gafams, and so on. 49 and the risk of simultaneous ownership of shares in competing companies by institutional investors, known as “common ownership”. 50 Think of the power of agrochemical companies to control the regulator in areas with vital consequences for biodiversity and human health. 51

Risks of recession and crisis

Not only do markets not spontaneously balance (i.e., the supply of goods and services does not spontaneously equal demand), they are in fact always out of equilibrium. When (solvent) demand is too weak across the board, this imbalance automatically amplifies, culminating in a major crisis. The state must therefore ensure that this spiral is avoided through appropriate policies, and intervene massively if such a crisis occurs. This is what we explain in our fact sheet on the economists Hyman Minsky and Irving Fisher, who helped to make the mechanism of economic crises understandable.

Conclusion

If humanity is to avoid going off course, it is clear that the balance of power between capitalists, states, “civil society” and Nature must be powerfully rebalanced. Here, we argue in favor of an in-depth reform of capitalism, without suggesting its abandonment – a project that is as vague as it is uncertain in an overly constrained timeframe.

Seen from a distance, there are four obvious ways to get there:

Take significant steps to adjust the existing system

The first is to bring about changes in social, economic and financial policies, making it possible to limit anthropogenic pressure on Nature and reduce social inequalities, without profoundly calling into question the current framework (by pursuing the advances of the Pacte law in France, for example). This path must be followed in all cases – it’s a minimum – and particularly at European level, in the face of the perilous persistence of the framework of thought that presides over the conduct of budgetary and monetary policies. The measures to be taken are, in any case, significant: an ecological reconstruction plan incorporating binding measures to achieve carbon neutrality and halt artificialisation, financial regulations, reform of the property market, tax reform (new income and wealth tax), etc.

Strengthening the legitimacy and power of public authorities in the face of multinationals

From a certain point of view, it’s a question of “turning back the clock”. “Demondialization”, “demarchandization”, banking separation (which was implemented by Roosevelt between the wars, then abandoned at the end of the 20th century), rehabilitation of a strategist state, possible nationalizations… This path is more ambitious and, if taken, would facilitate the measures proposed in the first. The COVID crisis and the war unleashed by Vladimir Putin make it more acceptable. 52 by the elite who have never ceased to advocate free trade and the illusion of soft trade to justify globalization.

Changing accounting rules by going the triple capital route

Accounting rules are binding on economic players. If they have to include expenditure on “repairing damage to human and natural capital” in the calculation of “profit”, they will be prompted to make decisions adapted to this double constraint, which at this stage is, in their eyes, only a very loose one. If they have to preserve natural and human capital in the same way as financial capital, this will have a profound effect on their trade-offs. Multi-capital accounting (which takes into account not only financial capital, but also human and natural capital, so that they can be better preserved) remains capitalist, but completely transcends the still largely dominant vision of capitalism.

National accounting, based on business accounting, would be reformed accordingly. We could expect an in-depth reform of GDP and social “well-being” indicators.

This path needs to be explored without delay. Barring a major crisis, it will take several years and will require international cooperation and a very strong political will.

Transforming the institutional framework

The fourth path consists of a parallel development :

- the governance of companies by including employees (co-determination) and, where appropriate, representatives of Nature in management bodies;

- democratic institutions, such as the creation of a “chamber of the future”. 53

This route would obviously have a greater impact as a complement to the previous one. The possible timetables are not the same, since this fourth path is accessible at national level, whereas accounting reform can only be envisaged at European level, at least.

Find out more

- Anton Brender, Capitalisme et progrès social, La Découverte, 2020

- François Crouzet, Histoire de l’économie européenne, 1000-2000, Albin Michel, 2000.

- Pierre-Yves Gomez, Le capitalisme, PUF, Que sais-je? 2022.

- Branko Milanovic, Le capitalisme sans rival, l’avenir du système qui domine le monde, La Découverte, 2020.

- Jacques Richard and Alexandre Rambaud. Révolution comptable – Pour une entreprise écologique et sociale, Éditions de l’Atelier, 2020.

- See for example Hervé Kempf, Que crève le capitalisme Le Seuil 2020. ↩︎

- See Andreas Malm, Anthropocene versus history. Global warming in the age of capital. La Fabrique Éditions, 2018. ↩︎

- Popularized in the early 21st century by scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, the concept of the Anthropocene refers to a new geological era characterized by the impact of human activities on our planet. Although the concept is widely used, there are still a few steps to be taken before this new era (which geologists date back to the mid-20th century) is officially adopted by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS). Find out more on the UISG’s dedicated working group website. ↩︎

- See for example the article Is capitalism responsible… for the destruction of the biosphere and the explosion of inequality? on Alain Grandjean’s Chroniques de l’Anthropocène blog, 2017. ↩︎

- On this subject, see Pierre-Yves Gomez’s book, Le capitalisme PUF, Que sais-je? 2022. ↩︎

- See, for example, Bruno Amable’s book Les cinq capitalismes. Diversité des systèmes économiques et sociaux dans la mondialisation, Le Seuil, Collection “Économie humaine”, 2005. ↩︎

- Salaried employment only became widespread in “capitalist” economies at the end of the 19th century, even if it had appeared earlier. The development of the digital economy, with the growth of platforms, is in the process of calling into question the importance of salaried employment. The employment contract is seen as too rigid by these new capitalists, who prefer the more flexible, less costly and far less protective self-employed status for the worker. Ongoing lawsuits against “platforms” such as Uber will undoubtedly bring about changes in this area, at least in Europe. ↩︎

- For a better understanding, see the failure to take nature into account in accounting in our module on business accounting. ↩︎

- This makes the question of the distribution of income from capital and labor one of the central issues of political economy. ↩︎

- See “Les salariés aux conseils d’administration : tour d’Europe”, Zonebourse, March 25, 2021. ↩︎

- In his book Le capitalisme sans rival Branko Milanovic suggests calling this form of capitalism “political capitalism” (as opposed to the “meritocratic liberal” capitalism we call “neoliberal financial” in this article). It seems more neutral to us to call it “state capitalism”, to emphasize the weight of the state apparatus in decision-making. On the other hand, to say that this capitalism is “political” may suggest that neoliberal capitalism is not, which is obviously not the case. ↩︎

- A company’s “stakeholders” are all those who have a direct relationship, monetary or otherwise, with the company: shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, service providers and subcontractors, bankers and other lenders, the State, social organizations and local authorities, neighbors where the company is located, associations and NGOs… ↩︎

- In his Report on Corporate Governance Models for the ILO (2020), Olivier Favereau defines co-determination as a model of “corporate governance” which includes employee representatives in a significant proportion of the “company’s” governing bodies (board of directors and/or supervisory board), with the same prerogatives as shareholder representatives. ↩︎

- This construction is part of an overall movement, involving both governments and private players. It cannot be said to be the prerogative of the private sector, which has always needed public institutions. ↩︎

- As Thomas Lagoarde-Segot writes, ” it was only after a long and tumultuous technical and social metamorphosis (described in particular by Karl Polanyi, in his book ‘ The Great Transformation’) that the English bourgeoisie succeeded in anchoring two principles in rights: land acquired a fluctuating price on the ‘land market’, and human labour capacity was exchanged for a fluctuating wage on the ‘labour market’”. ↩︎

- The majority of social achievements (in labor law, the right to strike, etc.) were the result of social conflict, although a few individual bosses were exceptions. See Anton Brender, Capitalisme et progrès social La Découverte, 2020. ↩︎

- The idea of leaving market forces to their own devices was widespread in 18th-century French liberal economics. The complete phrase, “laissez faire, laissez passe”“r” is attributed to Vincent de Gournay in 1752. ↩︎

- Named after John Maynard Keynes, who first theorized that state intervention could be beneficial to the economy. See, for example, his book The End of Laissez-faire: The Economic Consequences of the Peace, Prometheus Books, 2004. ↩︎

- Born at the end of the 19th century with Bismarck in Germany, the concept of a welfare state is opposed to that which limits the role of the state to regalian functions (i.e., the exclusive competence of the state: justice, police, national defense, diplomacy…). The welfare state intervenes in the social sphere, to ensure a minimum level of well-being for the population, in particular through the social protection system. It also intervenes in the economic sphere. ↩︎

- The system set up after the 1944 Bretton Woods conference was a fixed exchange rate system with a gold exchange standard based on the dollar alone. This system came to an end in the early 1970s, following US President Richard Nixon’s decision to suspend the convertibility of the dollar into gold. Find out more about the Bretton Woods system in the currency module. ↩︎

- See, for example, Jean-Luc Gréau, The Neoliberal Secret Gallimard, 2020, and Branko Milanovic, Le capitalisme sans rival, l’avenir du système qui domine le monde La Découverte, 2020. Milanovic describes current American capitalism as “meritocratic liberal”, which seems odd to us, since he shows in his book that the intergenerational transmission of wealth and power (i.e., without merit) is a characteristic of this system. ↩︎

- Find out more in our module on business and accounting. ↩︎

- This thirst may well have been paralleled, in certain periods, by a certain restraint on immediate consumption and a preference for investment (as in the case of Britain’s industrial development in the 19th century). This short-term restraint is seen as favoring the long-term accumulation of capital, which remains the “fuel” of capitalism. ↩︎

- See Ragip Ege, La question de l’interdiction de l’intérêt dans l’histoire européenne. An essay in institutional analysis, Revue économique, 2014. ↩︎

- See the table on page 31 of Branko Milanovic’s book, Le capitalisme sans rival which compares the last three forms of capitalism in terms of income distribution. ↩︎

- With the exception of salaried executives, whose interests the owners of capital seek to align with their own by a variety of means (performance-related remuneration for shareholders, stock options, etc.). ↩︎

- This expression refers to the law of the globalized jungle: the competition of all against all. ↩︎

- The social economy is less subject to this law, even in the mutualist world, which demands a lower return on equity than that imposed by the financial markets. ↩︎

- Let’s emphasize that “profit”, in today’s corporate accounting, is calculated after the contribution of all market stakeholders (employees, suppliers, bankers, government), whereas at the macroeconomic level all these stakeholders benefit from the company’s activity. This accounting is done from the point of view of the shareholder and his capital, which is neither neutral nor “natural”, and could/should be called into question. More details on the fact that accounting vocabulary is not neutral in the module on the company and its accounting. ↩︎

- Thomas Piketty, in his book Capital et idéologie (Seuil, 2019) proposes a participatory socialism that Marxist critics say doesn’t offer a real way out of capitalism. ↩︎

- There are 800 million undernourished people in the world, a considerable number in absolute terms (source: FAO). But in relation to the world’s population, this represents only around 10%. It was only in the 19th century that humanity emerged from the fate of famine for all. Sadly, it could return to this fate if we continue to destroy natural resources. ↩︎

- See Deaton Angus, The Great Escape, Health, Wealth and the Origin of Inequality, PUF, 2016. ↩︎

- This notion of focus is not emphasized enough: industrial successes are always dependent on it. Successful entrepreneurs focus on precise, often quantitative objectives, with a sense of detail and perfectionism within the narrow confines of their project. He calls himself a “pragmatist” as opposed to those whose conduct is motivated by more global intentions, be they ideological, political or religious. ↩︎

- The Business of Promises. A treatise on modern finance, Seuil, reprint 2009. ↩︎

- Introduced by Johan Rockström and Will Steffen in 2009, the concept of planetary boundaries refers to nine environmental limits that must not be crossed, at the risk of causing drastic changes to living conditions on earth. The areas concerned are: climate, biosphere integrity, freshwater, biogeochemical flows, stratospheric ozone, introduction of novel entities, ocean acidification, land system change, and atmospheric aerosols loading. By early 2026, seven of the nine identified boundaries have been crossed. ↩︎

- For Yann Algan and his co-authors, this mistrust in France is one of the causes of “populism”. Yann Algan, Elizabeth Beasley, Daniel Cohen, Martial Foucault, Les Origines du populisme, Seuil, 2019. ↩︎

- Antoine Vauchez recently wrote a book on the return to favor of the obvious. Public, Anamosa, 2022. ↩︎

- It is regrettable that a lack of profitability should result in the private sector refusing to invest. But that’s the way it is, and the role of the State is crucial in creating the necessary incentives and obligations. ↩︎

- Find out more about the concept of externality in the module on economics, natural resources and pollution. ↩︎

- Contrary to a widely held belief following Garrett Hardin’s famous text, The Tragedy of the Commons, PUF 2018 (translation Dominique Bourg). See also the work of Elinor Ostrom and Benjamin Coriat (eds.), Le retour des communs. La crise de l’idéologie propriétaire, Les liens qui libèrent, 2015. ↩︎

- DNDI is an independent, non-profit research organization based in Geneva, with the aim of developing drugs for neglected tropical diseases such as Leishmaniasis, Sleeping Sickness, Chagas Disease and Helminthiasis. Its model is a hybrid one, involving the private sector, the public sector and civil society. ↩︎

- The impact of randomness on the distribution of wealth: Some economic aspects of the Wright-Fisher diffusion process, CES working papers, 2014. ↩︎

- See, for example, the article byAlexis Louaas, Moins d’inégalités pour plus de croissance, La vie des idées, 2019, and that by García-Peñalosa Cecilia, Les inégalités dans les modèles macroéconomiques, Revue de l’OFCE, 2017. This article takes stock of the theoretical arguments in this debate. ↩︎

- See Tancrède Voituriez, Emmanuelle Cathelineau, Françoise Rivière, Vaincre les inégalités, IDDRI, Regards sur la terre, April 2017. ↩︎

- See Gaël Giraud, Cécile Renouard, Le facteur 12, Carnets Nord, 2012. ↩︎

- See, for example, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, Le triomphe de l’injustice. Richesse, évasion fiscale et démocratie (trans. by Cécile Deniard), Seuil, 2020. ↩︎

- According to this hypothesis, the more a company produces, the less profit it generates per unit of output, and the more yields decrease. This could refer, for example, to the situation of a farmer who cultivates less and less fertile land. See Michel Volle’s article on “increasing returns”. ↩︎

- In economics, a natural monopoly situation exists when the production of a good or service by several companies is more costly than its production by a single company. ↩︎

- Acronym for the digital giants: Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft. ↩︎

- See, for example, the working paper Common ownership by institutional investors and its impact on competition, OECD, 2017. ↩︎

- See Stéphane Foucart’s book: And the world became silent: how agrochemicals destroyed insects Seuil, 2019. ↩︎

- See Premières leçons d’économie à tirer de la guerre menée par Vladimir Poutine, Blog des Chroniques de l’Anthropocène, 2022. ↩︎

- This would be a third parliamentary chamber: the Assembly of the Long Term or Chamber of the Future, whose mission would be to “represent” Nature and future generations. See Inventer la démocratie du XXIe siècle – L’Assemblée citoyenne du futur, Les liens qui libèrent and Fondation pour la Nature et l’Homme, 2017 ↩︎