This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

The quest for greater “liquidity” is often put forward to justify financial innovations that favour it (such as high-frequency trading), or to counter regulations that are supposed to harm it (such as the financial transaction tax). The quest for liquidity is thus seen as “the grail of financial players”. However, this polysemic term is not limited to the financial markets. The aim of this fact sheet is to clarify its meaning.

This fact sheet is a revised version of an article published on the Chômage et monnaie website. 1

What are assets? What is a liquid asset?

Liquidity” is inseparable from the notion of assets. Let’s start by defining this concept. An asset is a tangible or intangible “object” which has a present and/or future monetary value for its owner.

Objects in the literal sense, such as a car, an apartment or a work of art, are assets. But intangible entities, such as copyrights, patented processes or financial securities (shares or bonds bought on the stock market), can also be assets. However, to qualify as assets by accountants, all these objects must have a monetary value. A car has a monetary value because the owner can resell it. The same applies to copyrights. If an object has no monetary value, it cannot be entered in the accounts and is not an asset. For example, a liter of seawater is generally worthless today. Similarly, a brilliant but unformalized and unpatented idea cannot be an asset.

The value of the asset is quantified by the currency we can withdraw from it: for example, the value of a Renault share on a given date is 24 euros. It may be more or less easy to convert this asset into money. In the case of Renault shares, this is easy, since they are quoted on the stock exchange in real time, and are the subject of a large number of exchanges. 2 . For a factory, which is also an asset, it’s obviously much more difficult. It can only be bought by a small number of investors, its value is difficult to assess, and it takes a long time to sell it. In short, it’s not that easy to turn a plant into hard cash.

This is where the notion of liquidity comes in. An asset is highly liquid if it can be sold quickly at a fair price. Conversely, an illiquid asset is one that is difficult to sell at a fair price.

The most liquid asset is legal tender, the ultimate liquidity. Assets that can be traded on a market with a large number of buyers and sellers, such as the shares of large corporations, are also highly liquid. However, they are not quite as liquid as money, since the probability of the stock itself (the company going bankrupt) or of the stock market collapsing, although low, is not zero. As a result, stocks can be sold at a loss. Real estate, on the other hand, is not very liquid, because the sale can be long, uncertain and generate capital losses (selling the asset for less than its acquisition price).

By extension of language, liquidity refers to the quantity of liquid assets owned. Generally speaking, these are money, deposit accounts or liquid savings accounts (such as Livret A passbook savings accounts), or securities that can be immediately realized at a virtually certain value, i.e. short-term debt securities (money market securities). These liquid assets are generally held to cover the risk of unforeseen expenditure. For example, a company may face a risk that business will not be done, and therefore suffer a shortfall in exceptional cash inflows. If it has a lot of cash, it will cope more easily than if it has none at all.

Liquidity and financial markets

As mentioned above, liquidity is seen as the “holy grail of financial markets”. Economists Yamina Tadjeddine and Hélène Raymond sum up the reason why.

“Liquidity is a social quality of assets, designating the ease of acquiring or selling an asset within a short time at the desired price. Long-term financial securities are essential for financing investment, but they are intrinsically illiquid: the capital committed will be recovered at the end of the loan period in the case of a loan, or at the rate of annual dividends in the case of a share. As a result, the committed capital is permanently blocked, and the holder is deprived of its use. The development of secondary financial markets – where securities that have already been issued are traded – improves liquidity, by enabling the holder to sell a security at any time. 3

The liquidity of financial securities (shares, bonds), made possible by the development of secondary markets, ensures that investors in these securities can quickly convert them into money if they have to deal with unforeseen circumstances (the loss of a job, for example), or if they wish to allocate their financial capital to something else (buying an apartment). In this way, it greatly facilitates the mobilization of capital to finance investments in the productive economy. Without it, far fewer people would be prepared to risk their financial assets on projects that don’t directly concern them.

It should be noted, however, that this liquidity of financial securities is of course not a sufficient condition for financing the productive economy.

It’s also a double-edged sword. Liquidity gives the illusion of unconditional reversibility of financial decisions. But the promise of liquidity, i.e. the promise of always finding a counterparty without loss of capital, can only be guaranteed as long as expectations are heterogeneous. If everyone thinks the market is going to collapse, it will indeed collapse! Nobody will want to buy anymore. Even if this belief that the market will collapse is unfounded, it will bring it about. This is what we call a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So, in the event of a financial crisis, markets become illiquid: no one wants to buy stocks, everyone wants to sell, and prices plummet. The market is said to be a one-way street. This is how you can read in the newspapers that billions have gone up in smoke in just a few days.

Bank liquidity

Banks are financial institutions that are structurally vulnerable to liquidity risk, i.e. the risk of being “unable to maintain or generate sufficient cash resources to meet their contractual payment obligations, or to do so only under very unfavorable conditions”. 4

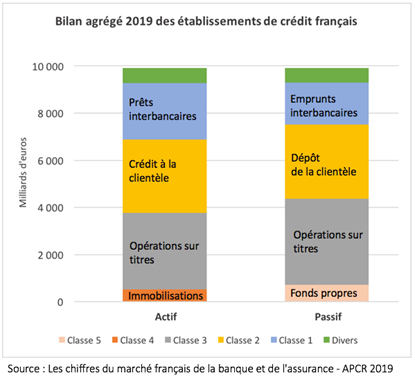

This intrinsic vulnerability is linked to the structure of banks’ balance sheets, and fundamentally to their power to create money: contrary to popular belief, they do not have the equivalent in deposits or savings of what they lend (even if their balance sheets are “balanced” by definition).

Liabilities are what the bank owes: they comprise shareholders’ equity, customer deposits and bank debts contracted with other banks and on the financial markets, a large proportion of which are short-term or very short-term. A bank’s liabilities are therefore fairly liquid, in the sense that customers can withdraw money from their accounts at any time, and short-term debts are highly reversible (creditors may not renew them). This is typically what happened on August 9, 2007, when the interbank market froze, with banks refusing to lend to each other.

Conversely, the bank’s assets are relatively illiquid: while some of the financial securities held by the bank can, in theory, be sold at any time, this is not the case for loans granted to its customers (businesses, households).

The bank must constantly ensure that it is in a position to meet its liabilities: to be able to settle its position with other banks (resulting from the various payments made by its customers via cheque, transfer or credit card), to repay its loans, to supply bills withdrawn from counters or cash dispensers (the extreme case being a ” bank run “), and so on. 5 ).

It can also sell assets, but as we have seen, these are not very liquid, and may become illiquid in the event of a financial crisis (when all financial market players seek to sell their assets at the same time). It can also refinance itself with the central bank, borrow from other banks on the interbank market, or issue bonds. But only if people agree to lend to it.

Liquidity risk therefore arises when a bank is unable to meet its liabilities, not because it is not solvent (i.e. it does not have enough assets to cover its debts), but because its assets are not liquid enough, or because it is unable to refinance itself.

But liquidity risk is a systemic risk: it can destabilize the entire financial system via chain reactions, as illustrated by the 2007-2008 crisis. The crisis began with a liquidity crisis on the interbank market in August 2007.

The interbank market

The interbank market is reserved for exchanges between banks. Due to the millions of transactions carried out daily by their customers, banks are constantly in debt or credit with each other. To settle their positions 6 to each other, banks in surplus lend to banks in shortage. These loans are short or very short term (between 1 day and 1 year). The central bank also intervenes on the interbank market by lending liquidity (see money module).

Following the difficulties encountered by several financial institutions as a result of the bursting of the securitized “subprime” credit bubble 7 bubble burst in 2008, mistrust has taken hold of the interbank market. Faced with considerable uncertainty about their direct and indirect commitments to securitized financial products containing subprime loans, banks stopped lending to each other.

A liquidity crisis is therefore characterized not by a lack of liquidity, but by a halt in its circulation. If the flow of liquidity is not restored, the consequences are disastrous: a bank that cannot meet its customers’ demand for liquidity is, by definition, insolvent (and may, by contagion, cause other financial institutions to become insolvent as well). In a liquidity crisis on the interbank market, some banks are “over-liquid”, yet refuse to lend to others with liquidity needs, or agree to do so at prohibitive rates, for fear of “counterparty risk”. 8

The system was only saved from collapse in 2008 by the massive intervention of central banks, starting with the ECB and the FED, which took the place of the market. They became the central counterparty, absorbing liquidity from banks with surplus cash and lending it on a massive scale to banks with liquidity needs, to prevent them from defaulting. They have also created liquidity ex nihilo (central bank money. See money module) in order to lend or supply it to banks.

Finally, a liquidity crisis can lead to an insolvency crisis. As assets become illiquid, their price plummets. The larger a bank’s portfolio of financial securities, the more losses it will incur as a result of falling asset values, and the more it will have to absorb these losses with its capital. If this capital is insufficient, the bank will go bankrupt.

- Alain Grandjean, “La notion de liquidité”, Chômage et monnaie, May 2005. ↩︎

- Unless the market becomes inactive due to a financial crisis, or Renault’s share price collapses (meaning that all market participants want to sell the stock and nobody wants to buy it) due to a scandal or the company’s poor financial results. ↩︎

- Yamina TADJEDDINE and Hélène RAYMOND,“Liquidity, high-frequency trading and index funds”, in Christian de Boissieu, Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran (eds.), Les Systèmes Financiers. Mutations, crises et régulation, Economica, 4th edition, February 2013. ↩︎

- 10 years on… Bilan des réformes bancaires et financières depuis 2008: avancées, limites, propositions, Terra Nova, 2018. ↩︎

- A ” bank run ” is a phenomenon, usually self-fulfilling, in which a large number of a bank’s customers fear that it will fail and withdraw their deposits en masse. ↩︎

- The term “position” refers to a contingent debt or claim. ↩︎

- Subprime mortgages are high-risk property loans granted by banks to low-income American households with insufficient collateral to qualify for a normal “prime” loan (either because their income is low or uncertain, or because they have had financial difficulties in the past). These loans were securitized by the banks concerned, i.e. transformed into financial securities that could be traded on the markets. The risks carried by these loans were thus spread far beyond the banks that had granted them. See the securitization factsheet. ↩︎

- Counterparty risk is the risk of default by the counterparty (in this case, the bank borrowing liquidity) in a financial transaction. ↩︎