This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Initially designed to hedge the risks incurred by economic agents, derivatives have essentially become speculative securities, themselves sources of risk.

The emergence of derivatives at the end of the Bretton-Woods system

In the 1970s, the end of the Bretton Woods system and the introduction of a floating exchange rate(see the module on currency) created a new risk for those involved in international trade: currency risk. If a French manufacturer undertakes to sell his production in dollars within three months, he doesn’t know how much this will earn him in national currency (the franc or the euro, depending on the period), since the franc exchange rate fluctuates continuously.

Banks therefore designed and sold new products – currency options – to hedge this risk. After currency options, derivatives developed in successive waves, expanding the range of their “underlyings” (commodity prices, exchange rates, interest rates, credits) and their tools (forward purchases and sales, options, swaps, structured products, securitization, etc.).

What are derivatives?

There are two types of financial securities:

– Simple” securities such as equities, bonds, currencies and commodities.

-Derivatives are used to hedge the risk associated with a simple product (known as the underlying).

For example, if I’m an industrial user of energy, I may want to protect myself against the risk of a price rise, by buying it at a fixed price now, even if my physical purchase takes place at a later date. If I’m a saver and invest in debt securities, I may want a guarantee in the event of issuer default. In both cases, I have to pay the cost of the derivative, but it’s much less than what it would cost me to materialize the risk I’ve hedged against.

Derivatives are therefore both instruments for hedging against risks and financial securities that have a value (variable…) and can then be traded on financial markets.

The explosion of derivatives in the 2000s

Financial products and services of this kind are not new: they were originally born of the need for economic players to protect themselves against risk. The risk of being robbed by pirates was taken by merchant sailors in the Middle Ages. If I’m a farmer selling cereals, I may want to protect myself against the risk of a fall in the price by selling them now, even if my physical sale takes place later. Farmers and manufacturers produce, while financiers and insurers manage risks.

Derivatives stem from a similar need (for companies to hedge against the risk of price fluctuations). What’s new, however, is their extraordinary development. As Thierry Philipponat, who lived through this period of creative effervescence from the inside as a trader, clearly demonstrates, this development is based on an intrinsic logic: the supply of financial products has generated demand, often from other financial players. 1 .

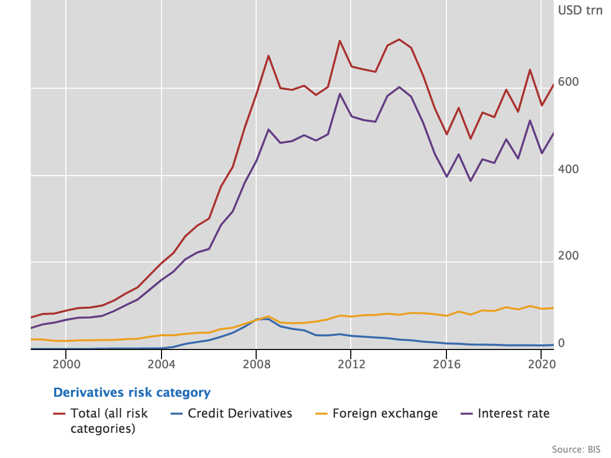

Notional outstandings 2 derivatives represented, at the end of 2019, more than $558,000 billion, or over 600% of global GDP, clearly demonstrating the disconnect between their development and the risks they are supposed to cover.

Oil derivatives currently represent more than ten times the physical volumes of oil in circulation, demonstrating the hypertrophy of finance compared with the non-financial economy, and the fact that commodity prices are set more by derivative transactions than by the market conditions of the underlying products.

They have become a source of speculation rather than a response to real economic needs. They have negative consequences for the economy: they are traded opaquely, their high yields attract savings to the detriment of investment in the productive economy, and they have been at the heart of recent financial crises (CDS used to speculate against government debt, CDO in the