This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Shadow banking refers to financial activities or entities that carry out bank-like activities without being subject to the same regulations. Examples include securitization funds, which were at the heart of the 2008 crisis, and hedge funds. Although this sector does not necessarily include entities of global scope, it has spread throughout the world.

An opaque and risky sector

Without going into the details of an extremely complex sector, let’s just mention two characteristics:

- This sector carries the same risks as banks, without the same safeguards: no minimum capital (unlike banks), no product registration room, no regulatory body.

- Shadow banking entities are very close to banks, of which they are often subsidiaries. When they are independent, they are linked to traditional banks by financing operations, credit or liquidity lines, or cross-investments.

It is this interdependence with the banks that is a source of concern. The failure of these entities could spell trouble for systemic banks, and thus for the financial sector as a whole.

In the wake of the 2008 crisis, G20 leaders felt it necessary to monitor this sector and consider its regulation. In October 2011, they tasked the Financial Stability Board (FSB) with 1 to produce an annual assessment of global trends and risks in non-bank financial intermediation. This report, published since 2012 2 is very useful, as it not only shows the evolution of shadow banking, but also of the global financial system as a whole.

An expanding sector

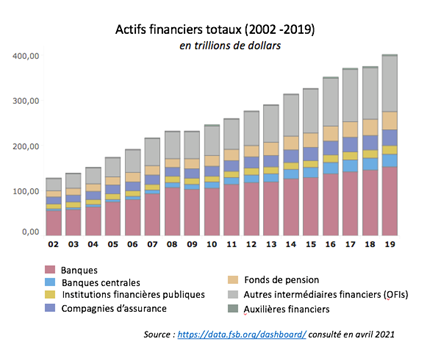

In its measurement of the overall financial system, the FSB distinguishes between banking players (banks, central banks and public financial institutions) and thenon-bank financial intermediation (NBFI) sector, which includes insurance, pension funds, financial auxiliaries and other financial intermediaries( OFIs). The latter constitute the broad measure of shadow banking. As can be seen from the following graph, the share of OFIs in the overall financial system has risen steadily, from 21% in 2002 (around $27,500 billion) to 31% in 2019 ($124,000 billion).

Source This graph is taken from the scoreboard maintained by the Financial Stability Board.

The narrow measure of shadow banking is a sub-section of OFIs. According to the definition used by the FSB, it includes “non-bank financial entities that the authorities have assessed as being involved in credit intermediation activities that may present bank-like financial stability risks, based on the FSB’s methodology and classification guidelines”. This is where the risks to the financial system are concentrated.

By this measure, shadow banking has grown from 27,000 billion assets in 2006 (when the series begins) to 57,000 billion assets in 2019. In both cases, this represents around 14% of the global financial system.

The importance of undoing the links between banks and shadow finance

As Gunther Capelle-Blancard and Jézabel Couppey Soubeyran explain , the banking lobby is developing a line of argument “according to which the more we strengthen bank regulation, the more the banks transfer their risks to shadow banking entities. As shadow banking entities are by nature less regulated than banks, the conclusion is a demonstration of a formidable perverse effect: the more we regulate (by strengthening bank regulation), the more we deregulate (by encouraging the growth of shadow banking).

However, it is not inevitable that shadow banking will become the outlet for banking risks. It is through the links and connections that shadow banks and traditional banks maintain (lines of credit, equity investments, temporary swaps of securities for liquidity, etc.) that these risk transfers can take place.

Reducing these links also means reducing transfer possibilities. But the regulator has done little to undo them.

Find out more

- Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation, Financial Stability Board, 2020

- Yamina Tadjeddine, Laurence Scialom, “Banques hybrides et réglementation des banques de l’ombre”, Terra Nova, 2014

- Stijn Claessens, Lev Ratnovski , “What is Shadow Banking?”, Working paper, IMF, 2014

- Jézabel Couppey-Soubeyran, Blablabanque, le discours de l’inaction, Editions Michalon, 2015

- Created at the G20 London summit in April 2009, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) is an international organization whose mission is to assess global financial vulnerabilities, make proposals to address them, and promote cooperation between different financial supervisory authorities. Hosted by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), its members include representatives of national and international supervisors and regulators, as well as financial institutions. ↩︎

- Originally called the Global Shadow Banking Monitoring Report, since 2019 it has been called the Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation. All editions can be downloaded from the FSB website. ↩︎