This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

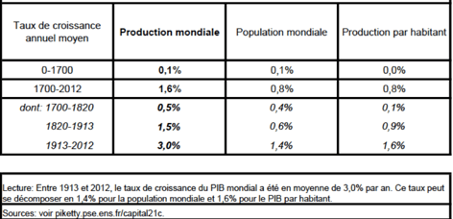

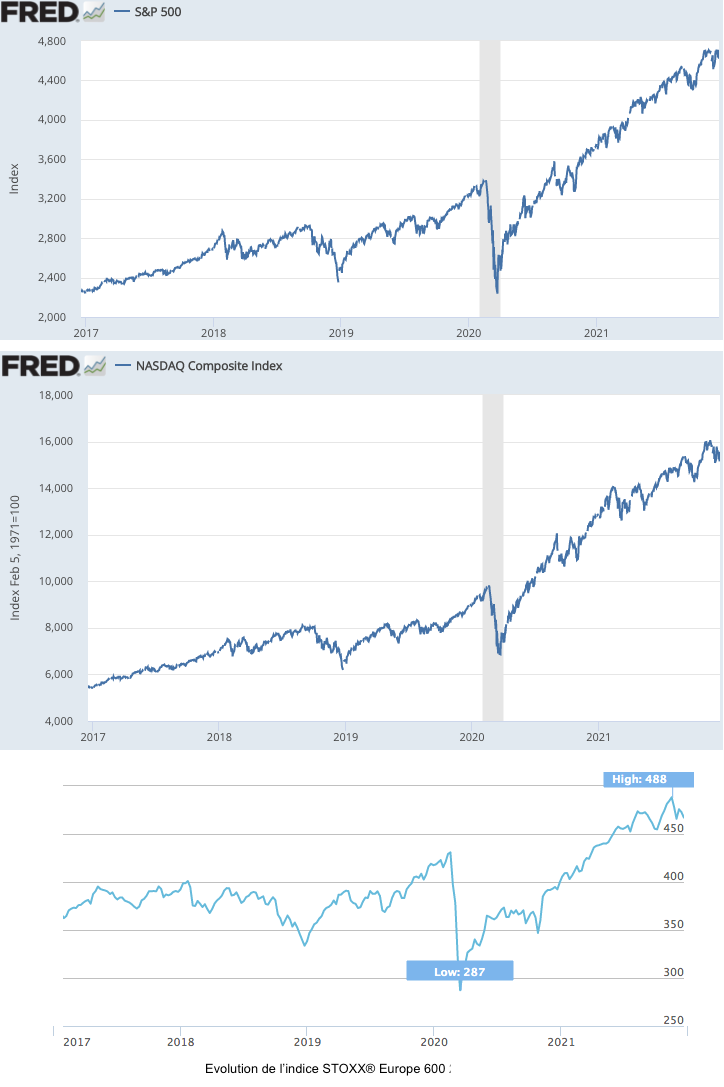

For decades, GDP growth, the flagship indicator derived from national accounting, has been at the heart of discourse on the progress of our societies and economic policy objectives. After the Covid crisis in 2020 (as after any crisis, indeed any war), the “resumption” of this growth was celebrated like the messiah.

However, we will see here that neither GDP nor its continued growth allow us to take into account planetary limits and social justice. 1 . We will also see that the construction of GDP raises methodological questions of a magnitude and importance that are generally underestimated. Finally, we’ll see that the driving forces behind macroeconomic dynamics (even for economists who regard economic growth as a central objective of economic policy) are still not well understood. 2 .

The question of growth obviously arises in very different terms depending on the stage of economic development. There is little doubt 3 that for “poor” countries, economic growth can be both socially and economically beneficial. It enables children and women to pursue a minimum level of education and become self-sufficient. It is a recognized condition for demographic transition. It is also the means to ensure a minimum level of medical and energy infrastructure.

Understanding the driving forces and limits of growth would be useful for countries that are going to bear the full brunt of the consequences of ecological crises. It would also be useful for the European Union and Japan, which seem to be mired (for almost 30 years in the case of Japan, and 10 years in the case of Europe) in a latent recession, rendering them incapable of launching a truly serious “green new deal”-type program, while anticipating a post-growth world where GDP will no longer be the appropriate indicator for assessing our economies.

Definitions

The aim of national accounting (NA) is to provide a global, quantified representation of the main dimensions of a country’s economy. The CN framework in force provides precise definitions of the main economic concepts and methods for calculating aggregates. 4 that characterize a national economy. Production, consumption, investment, GDP, unemployment, public debt, foreign debt, national wealth: all the figures that fuel political, economic and media discourse and public debate are derived from NC. At international level, the accounting framework currently in force is the 2008 SNA (System of National Accounts). In Europe, the ESA 2010 (European System of Accounts) applies.

Gross domestic product (GDP) measures the aggregate value added produced within the national economy, i.e. the total value of the production of goods and services minus intermediate consumption (goods and services transformed or entirely consumed during the production process). This indicator is therefore intended to measure the new value created through the productive activity of a national economy. InEssentiel 3, we’ll look at how GDP is calculated in detail, and how it can be interpreted in a number of different ways, which also makes it interesting.

Growth (or economic growth, or GDP growth)

GDP is published in value or current prices (i.e. nominal GDP) and in volume or constant prices (i.e. nominal GDP minus inflation). GDP growth refers to the change in GDP volume from one year to the next.

GDP per capita

To compare the economies of different countries, we use GDP by value (or by volume) as well as GDP per capita. It’s obvious that between a very large country (like the USA) and a small one (like Luxembourg), the level of GDP alone says nothing about the standard of living of the inhabitants. To be even more accurate, we evaluate GDP per capita in “purchasing power parity”, i.e., taking into account what incomes can buy.

This module benefited from the proofreading and comments of Didier Blanchet and Simon Chazel (the latter having also co-authored

Essentiel 8 on macroeconomic models

). Find here

the list of all TOE contributors

.

The essentials

GDP and its growth are central indicators of economic discourse and policy.

GDP is a measure of new production in a national economy over the course of a year.

This indicator, which came to prominence after the Second World War, still plays a major role in the orientation and evaluation of public policy. GDP and its growth are seen as the manifestation of the power of states, as a measure of the standard of living of their inhabitants, and as a sine qua non for achieving most public policy objectives (combating unemployment, financing social spending, ecological transition).

National accounting was born out of the great crises of the first half of the 20th century.

While the first attempts to estimate national income date back to the end of the 17th century, it wasn’t until the 1930s that national accounting really began to take off, in other words, the desire to provide a global, quantified representation of the main dimensions (production, income, employment, consumption, productive capital, debt, etc.) of a country’s economy.

The two world wars and the crisis of 1929 demonstrated to governments the importance of equipping themselves with tools for measuring the national economy.

The crisis of 1929 was an important moment in the development of GDP.

On the one hand, it calls into question the then-dominant view in economics that supply creates its own demand, and that public intervention should be kept to a minimum to ensure that the economy functions at its best. Not only were crises possible, but state intervention appeared necessary to overcome them. Inspired by the ideas of economist J.M. Keynes, the New Deal launched by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 was designed to boost the economy by increasing aggregate demand through public spending (public works, public employment, social spending).

On the other hand, the crisis of 1929 highlighted the inadequacy of the statistical apparatus available to public players. If government intervention in the economy was no longer taboo, it still needed to have the elements to guide and evaluate its actions. It was to meet this need that Simon Kuznets commissioned the U.S. Senate to produce a report on the evolution of National Income from 1929 to 1932. 5 . This work constituted the first (rough) calculation of an indicator approaching GDP.

The production base, a determining factor in power

The two world wars highlighted the importance of mobilizing a country’s productive base to sustain the war effort and win the war. This heightened the interest of work aimed at strengthening statistical tools. During the First World War, the first national accounts were drawn up in various countries 6 . Following the Bretton Woods conference in 1944, GDP became the reference indicator for measuring and comparing the size of economies.

The post-war period saw a deepening of this statistical and accounting production dynamic to accompany the reconstruction of Europe and, in the United States, the reorientation of war production towards peacetime goods and services, as well as their disposal. The Thirty Glorious Years, marked by strong growth, full employment and rising living standards, validated economic growth in the collective imagination as an instrument of social progress.

National accounting developed in parallel in various countries before being standardized internationally with the adoption of the 1993 System of National Accounts.

7

(which will be updated once to give the 2008 SNA).

The SNA is a highly detailed nomenclature that explains all the definitions, rules and conventions used to draw up a country’s national accounts and major economic aggregates. It applies to every country in the world, although certain countries and zones may adapt it to suit local conditions. In the European Union, for example, the European System of Accounts(ESA 2010) applies.

One of the great strengths of GDP, and of national accounting in general, lies in this universalism of standards and conventions, which makes comparisons over time and between countries possible.

This brief history shows the extent to which the development of national accounting (and its central indicator, GDP) is the result of the dramatic events of the first half of the 20th century. GDP, as an indicator, came into being because it was felt necessary to measure production in detail in order to emerge from the crisis and support the war effort, followed by reconstruction. Such concerns have not disappeared today.

“Alongside the mobilization of resources for the war economy, it was attempts to forge effective demand management as a way out of the economic slump caused by the financial crisis of 1929 that prompted the introduction of national accounting. The focus on GDP is therefore not simply a convention. It certainly stems from a singular historical trajectory, combining the experiences of the twentieth-century wars and the Great Depression. But these two sources derive from ever-present constraints: on the one hand, the balance of power within the “concert of nations”; on the other, the electoral weight of a policy to support employment. Continued growth is therefore partly a response to structural imperatives.

Nearly a century after its birth, GDP remains at the heart of economic discourse and policy.

In a 2013 study, the think tank The Shift Project ranked the different uses of GDP in order to assess the extent to which other indicators could replace it.

As can be seen in the box below, this classification gives the impression of an omnipresent “all-purpose” indicator, whatever the subject. It can be used to assess a country’s power (comparing countries according to their GDP in value terms) or wealth (comparing GDP per capita), to calibrate public policies (limiting public spending, setting environmental objectives, R&D targets), to draw up budget forecasts, or to calculate countries’ contributions to various international organizations.

GDP, an all-purpose indicator

Symbolic uses

GDP is used to create and share a common representation of a given concept (wealth, power, progress). These symbolic uses also manifest themselves in the desire to make it the standard of comparison for all economic data: education/GDP, health/GDP, investment/GDP.

Operational uses

GDP is used to trigger concrete action. For example: defining the contribution (and often the voting rights) of States to supranational budgets. 9 (European budget, IMF, World Bank); distributing international funds (European regional development funds or development aid distributed according to GDP/capita); drawing up budget forecasts (forecasts of GDP trends are used to estimate a level of budget revenue and therefore a spending capacity).

Political uses

GDP is used by national governments or supranational institutions to legislate or regulate (e.g. to control public spending). 10 setting targets for specific policies 11 ).

Source Les usages du PIB, The Shift Project, 2013

This multiplicity of uses of GDP clearly demonstrates the centrality of this indicator. Most heads of government see GDP growth as the primary objective of economic policy, and indeed of public policy in general. It is seen not only as a sign of a country’s power and wealth, but also of its ability to meet the many ecological and social challenges it faces.

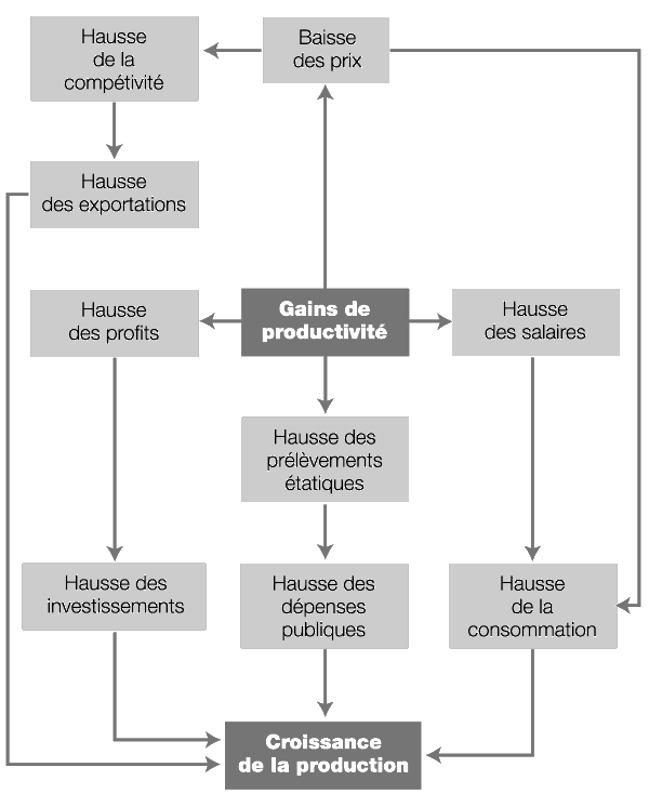

In a nutshell, the reasoning behind this deeply-rooted belief is as follows: GDP growth would increase employment, purchasing power, investment capacity and innovation. These are all necessary conditions for improving well-being or collective well-being, and for solving ecological problems, thanks to science, technology and human ingenuity. These are clearly the arguments put forward by economists when talking about growth and ecology.

The need for growth to drive the ecological transition

First of all, it should be remembered that the vast majority of economists working on growth do not include the ecological question in their work (see the Economy, natural resources and pollution module).

Schumpeterians 12 believe that “green innovation” is the solution to the problem posed by the polluting nature of GDP growth. These supporters of “green growth” see it as the path to ecological transition, by enabling the necessary technical progress. We’ll come back to this inMisconception 6.

For the “socio-liberals”, growth means first and foremost more income, and therefore more resources to improve people’s lot and reduce social inequalities. The fight against climate change will not be possible without growth to compensate for the loss of income suffered by those who lose out as a result of the transition (which will eliminate jobs in activities dependent on fossil fuels).

For neo-Keynesians, reducing greenhouse gas emissions requires a great deal of investment, which in turn generates more growth, at least initially.

Despite growing recognition of the limits of GDP, it remains at the heart of policy objectives.

As we shall see inEssentials 5 and 6, GDP and the quest for its growth are the subject of much criticism: they are no guarantee of improved living conditions for populations, and growth is accompanied by massive environmental degradation.

Initially voiced by researchers and activists, the inadequacies of GDP as an indicator of a society’s good health are now widely recognized at institutional level, as demonstrated by European initiatives to go beyond GDP and place other objectives at the heart of public policy (see below). However, despite these positive developments, it has to be said that the objective of growth (now described as green, sustainable or inclusive) remains central.

The development of a “beyond GDP” strategy in the European Union

Institutional recognition of the limits of GDP began with research. In 2007, the European Commission launched the Beyond GDP initiative to develop “indicators that are as clear and attractive as GDP, but take greater account of the environmental and social aspects of progress”. In 2009, this led to the publication of the roadmap Beyond GDP: measuring progress in a changing world. 13 .

The same year saw the publication of the report by the Stiglitz, Sen and Fitoussi Commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress, commissioned by the President of the French Republic. Composed of eminent economists, including several Nobel Prize winners, the commission’s work marked a milestone in the institutional recognition of GDP’s limitations, for while the criticisms were widely known, it was the first time they had been voiced by mainstream economists. The report’s recommendations on the measurement of well-being and sustainability will feed into the work of various European statistical bodies.

At the political level, the beginning of the 21st century is also marked by the increasing display of social and ecological objectives. This is the case, for example, with the EU 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, adopted in 2010 14 .

In its Conclusions of October 24, 2019, the Council of the European Union calls on the Member States and the Commission to “integrate concern for the welfare economy horizontally into national and Union policies, and place people and their well-being at the heart of policymaking.”

Taking office at the end of 2019, the Commission chaired by Ursula Van der Leyen is going one step further by making the Green Deal for Europe one of its six strategic priorities. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, resilience 15 becomes “a new compass for EU policies.”

Despite these advances, growth remains the overriding objective

Thus, the rationale for including welfare economics in all public policies is that it “is of key importance for economic growth, productivity, long-term fiscal sustainability and social stability in the Union.” Theinfographic produced by the European Council to explain what welfare economics is shows the extent to which people’s well-being and economic growth remain intrinsically linked in official discourse.

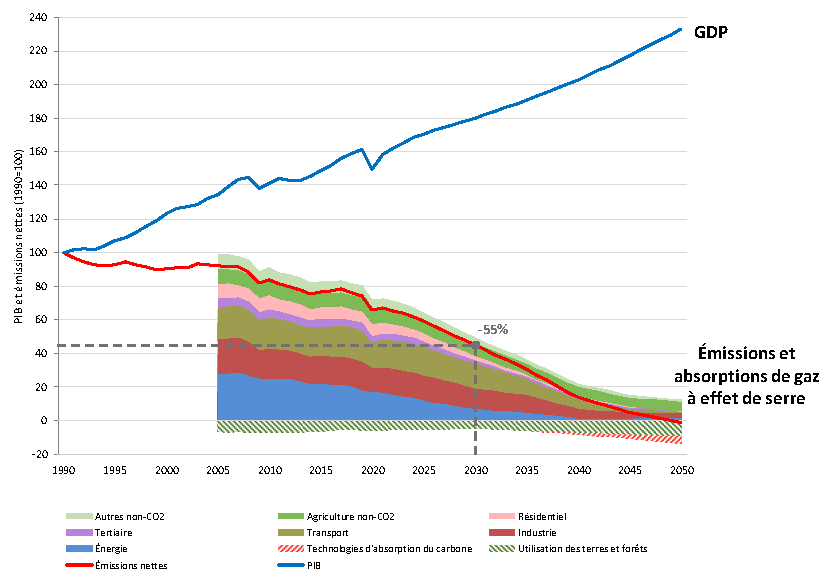

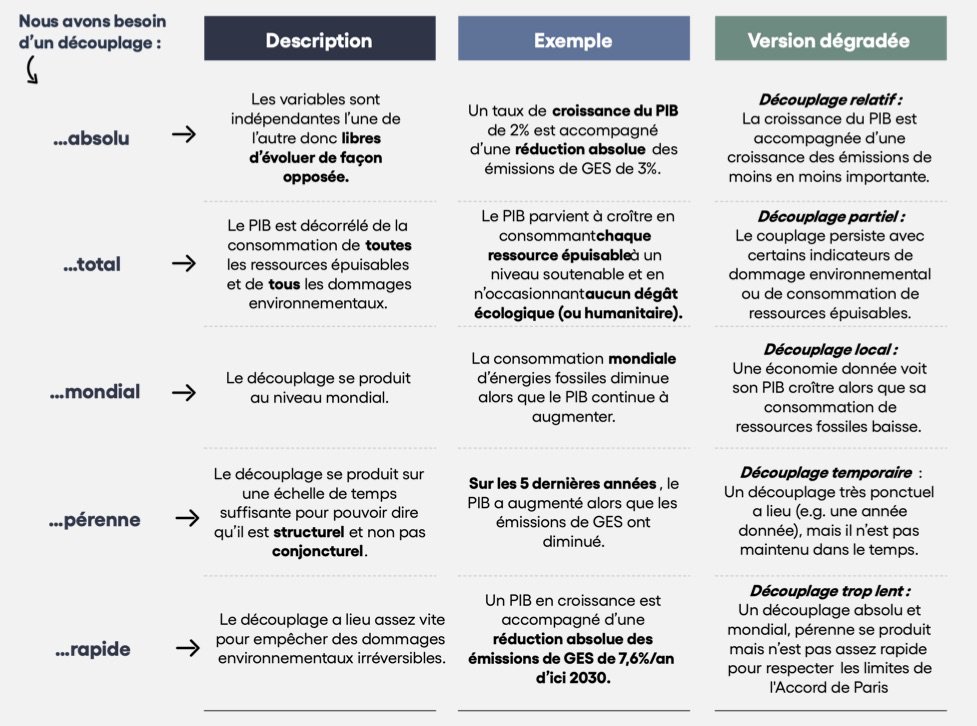

The Green Pact for Europe is described by the Commission as a “new growth strategy” that “aims to transform the EU into a just and prosperous society, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, characterized by zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, and in which economic growth is decoupled from resource use.”

Here is the trajectory presented by the Commission to achieve the climate neutrality objective at the heart of the Green Pact:

Source Stepping up Europe’s 2030 climate ambition – Investing in a climate-neutral future for the benefit of our people, Communication from the European Commission, COM/2020/562

As can be seen, GDP growth remains central to the analysis. The presence of such a graph in a document dedicated to climate policy illustrates the extent to which this objective is still perceived as at least equivalent to, if not a prerequisite for, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

As a final example, in the Porto Declaration on social issues adopted on May 8, 2021, the Heads of State meeting within the European Council welcome “the fact that the European social partners have drawn up a joint proposal for an alternative set of indicators to measure economic, social and environmental progress, which would complement GDP as a measure of well-being at the service of inclusive and sustainable growth.” The legitimacy of alternative indicators is fully recognized, but growth remains the ultimate goal.

Find out more

- The uses of GDP, The Shift Project, 2013

- Antonin Pottier, “Will the new wealth indicators modify growth? Les limites de la critique du PIB”, Le Débat, 2018.

- Benjamin Brice, “Why are we so attached to growth?”, Blog Un autre cap, October 20, 2021.

- François Fourquet (ed.), Les comptes de la puissance: histoire de la comptabilité nationale et du plan, éditions Recherches, 1980.

European Union countries pursue austerity policies in the belief that they are “growth-oriented”.

While the objective of growth is common to most governments around the world, the policies designed to promote it can differ greatly from one country to another, depending on the prevailing economic thinking.

Keynesian policies versus structural reforms

During the “Trente Glorieuses”, Keynesian-inspired policies prevailed. These were based on the importance attached to aggregate demand and to the steering of the economy by the public authorities: strict control of the financial sector, wage enhancement and redistribution policies, stimulus via public spending (major works) in the event of an economic slowdown, proactive industrial strategies and so on.

Since the 1970s, neoliberal-inspired policies have become the norm. The aim is to “liberate” growth by acting on the supply side, by reducing regulations and constraints (particularly tax constraints) weighing on companies and investors, by deregulating financial markets, by implementing structural reforms concerning the cost, duration and organization of work, and by controlling public spending (which would weigh on companies’ costs and harm their competitiveness).

The European Union has gone the furthest in this direction: the economic principles involved in this type of policy have been enshrined at the heart of the European treaties, i.e. at the very top of the EU’s hierarchy of norms. 16

Potential GDP at the heart of European software

Since the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, European economic governance has revolved around two budgetary rules: member states’ public deficits must be below 3% of GDP, and their public debt must not exceed 60% of GDP.

These rules were then refined to take account of the fact that the public balance depends in part on the economic climate: an economic crisis can lead to a cyclical rise in the deficit (lower tax revenues, higher social spending, stimulus policies). As a result, European and national authorities have endeavored to calculate the structural public balance (i.e., the balance that would have been recorded if GDP had been at potential – see box), with the aim of achieving a balanced position.

Potential GDP

Potential GDP is an unobservable indicator designed to measure what a country’s GDP would be if production capacities (labor and productive capital) were fully utilized without generating inflation. Calculating potential GDP makes it possible to determine another unobservable indicator: the structural public balance.

Find out more with our fact sheet on potential GDP and structural deficit.

These considerations are not just theoretical or technical: they have a profound impact on European public policy, to ensure that each country’s economy reaches its maximum production potential.

The “right” public spending, the “right” economic policy measures, are those that bring our economy back into line with potential growth. The aim is to close the output gap, i.e. the gap between actual growth and potential growth.

From an economic point of view, it is indeed desirable to fully utilize the production factors of labor and physical capital (machines, factories). 17 . However, the methodologies used to calculate this gap are more than scientifically questionable (see the fact sheet on potential GDP and the natural deficit), as are the public policy measures put forward in European texts to reduce the output gap.

These are so-called “structural” reforms, essentially aimed at cutting public spending, making the labor market more flexible and promoting innovation. This is how the “lightening” of labor laws, the elimination of “rents”, the simplification of administrative procedures, the deconstruction of public services, etc. are justified. In short, the measures that have been at the heart of European leaders’ economic programs for decades.

Thinking they are pursuing growth policies, European governments are in fact pursuing austerity policies, which obviously pose major problems for investment in the ecological transition.

The calculation of GDP is based on a number of conventions

Here, we look at how GDP is calculated, detailing how each of the major institutional sectors (see box) contributes to its formation.

In particular, we will see that it is the result of numerous conventions, which are themselves interpreted by national accountants. This makes international comparisons far less straightforward than they might seem. We’ll also see just how informative an indicator GDP is, once you get down to the nitty-gritty of its breakdown.

Gross domestic product is the main aggregate measuring a country’s economic activity. It corresponds to the sum of gross value added newly created by the country’s resident economic units in a given year, valued at market prices.

It provides a measure of the new wealth created each year by the country’s productive system and enables international comparisons.

As the definition above illustrates, GDP is traditionally presented as a measure of a country’s productive activity. As we shall see, there are in fact three ways of calculating it: by production, by income and by expenditure. This is quite logical: the production of goods and services enables the distribution of income, which in turn is used to consume and invest.

The national economy and institutional sectors

In national accounting, the national economy is made up of all resident institutional units, i.e. the various economic agents with the capacity to hold goods and assets, incur debts, carry out economic activities and, in short, carry out economic transactions with other units.

A unit is said to be resident from the moment it carries out economic activities on the territory of the country for one year or more. This is not a criterion of nationality: an immigrant worker is part of the French national economy, but a Frenchman working abroad is not.

Institutional units are grouped into five main sectors: non-financial corporations, financial corporations, general government, households (this sector also includes sole proprietorships) and non-profit institutions serving households (NPIs).

Resident institutional units can maintain relations with non-resident units, which are grouped together in a 6th sector, that of the “rest of the world”.

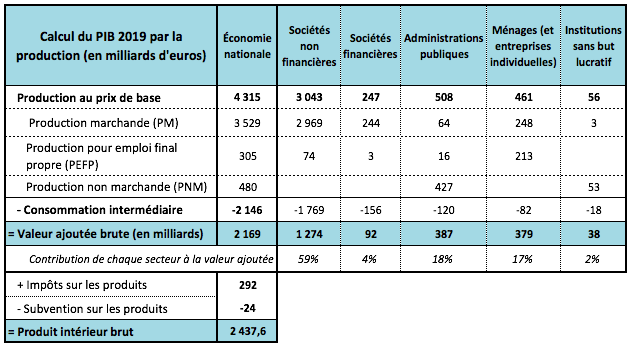

Calculating GDP by production

GDP is not a measure of production in the strict sense, but of the value added (VA) generated by the various resident units of a national economy over the course of a year.

As its name suggests, VA is the value of production added to the national economy. To calculate it, it is therefore necessary to eliminate double-counting, i.e. goods and services sold by certain producers that are used in the production of other goods and services.

To calculate GDP you need :

- Add up the value of production (market, non-market or for own final use – see box) achieved by all producers over the course of a year.

- Then, to avoid double counting, subtract intermediate consumption (i.e. goods and services transformed or entirely consumed during the production process).

- Finally, to obtain GDP, we need to move from the base price (the price received by the producer) to the acquisition price (the price paid by final consumers). We therefore add taxes on products (taxes, such as VAT, paid by final consumers at the time of purchase) and subtract subsidies on products (subsidies paid to the producer to reduce the prices paid by final consumers).

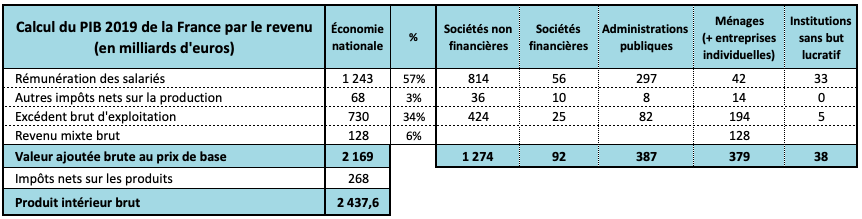

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, Tableau économique d’ensemble 2019 (production account)

In 2019, France’s GDP totaled 2437.6 billion euros. Nearly 59% of value added was generated by non-financial companies, 18% by general government and 17% by households. It should be noted in passing that public spending does indeed represent a contribution to GDP, and not a deduction from it, as is often claimed.

Note that GDP can also be broken down not by institutional sector, but by branch of activity (agriculture, industry, services, etc.).

National accountants distinguish three types of production

Marketable production (MP) is sold or intended for sale on a market. It essentially comprises goods and services sold at an “economically significant” price (i.e. covering more than 50% of production costs) or included in producers’ inventories. 18 .

Non-market production (NMP) is provided free of charge (or at an “economically insignificant” price). It includes services that are not sold because they are indivisible (defense, police, public lighting, maintenance of natural areas) or because of political will (education, health, access to culture, etc.). It is essentially provided by public administrations.

Production for own final use (PEFP) is the production of goods and services for the producer’s own final consumption or investment. Only households produce PEFP for their own final consumption (agricultural products kept by farmers, housing services produced by owner-occupiers, domestic services resulting from the employment of paid staff). All sectors can generate FPEI for their own investment: research activities, software development, machine tool manufacturing, construction (including household housing), etc.). 19 .

How are production limits defined?

In SEC 2010 20 production is defined as “an activity carried out under the control, responsibility and management of an institutional unit which combines resources – labor, capital, goods and services – to manufacture goods or provide services. Production does not include natural processes without human intervention or control.” (p.58)

- The spontaneous growth of natural resources (fish in the ocean, primary forests, groundwater renewal, etc.) is therefore excluded from production. Conversely, the growth of fish in fish hatcheries, of farmed animals, of trees cultivated for their fruit or timber are all part of production. This explains why clear-cutting a primary forest or cultivating a nature reserve results in an increase in production (and is therefore counted positively in GDP).

- The unobserved economy 21 is theoretically part of production. For example, national accountants must try to include “underground” production 22 i.e. production not declared to avoid taxes (under-declaration of sales) or social security contributions (undeclared work), by making estimates based on indirect sources (such as tax adjustments). Certain illegal activities are also included in the production perimeter, as long as they are the subject of a “common agreement” (for example: theft is excluded, but the sale of stolen goods is included). The inclusion of drugs and prostitution has been the subject of much debate. 23

- Production also includes non-market activities and activities carried out for oneself (see box above). Here too, the limits of what is and what is not included in GDP are conventionally fixed. Thus, the production of goods (food, construction) by households for their own consumption is part of production. On the other hand, domestic services (cooking, cleaning, childcare, care of the sick and elderly) are not included in the calculation of production (unless they are performed by paid employees).

How is production value calculated?

While the value of market production is determined by selling prices, this is not the case for the other two types of production.

PEFP is “estimated on the basis of similar products sold on the market. This production therefore generates a net operating surplus or mixed income.” If there is no market price for similar products, PEFP “is valued at production costs, plus an amount corresponding to the expected net operating surplus or mixed income”. 24

The PNM is valued by summing production costs. 25 This method has been the subject of much debate among national accountants. 26 While it has the advantage of being based on measurable quantities, it remains largely conventional, and there could be other ways of evaluating it. For example, if, like the PEFP, the PNM included a producer’s margin (operating surplus or mixed income), its amount would be higher, which would lead to an increase in the GDP of countries in which public services play an important role.

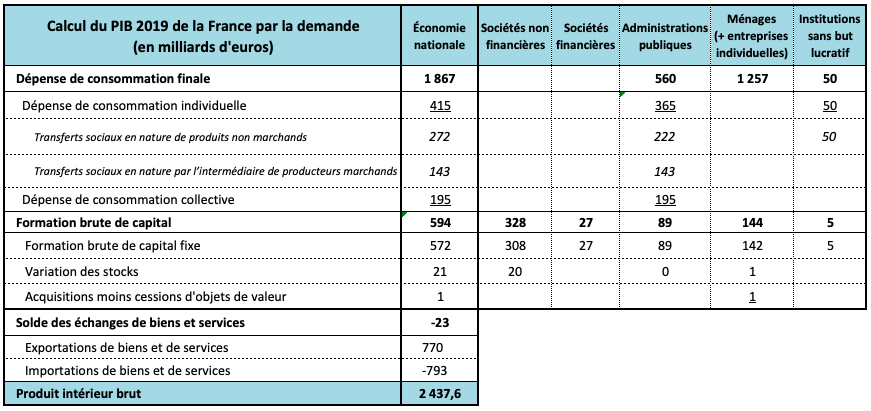

Calculating GDP by demand (or by expenditure)

GDP can also be calculated as the sum of all final expenditure (i.e. excluding intermediate consumption) by resident units, plus the balance of trade in goods and services with the rest of the world.

This approach shows whether GDP is driven by final consumption or by investment. The trade balance shows the extent to which domestic demand depends on imports (if this balance is negative) or the extent to which foreign demand contributes to GDP (if this balance is positive).

For example, in 2019, final consumption accounted for around 77% of France’s GDP, and investment (GFCF – see box) for almost 23%.

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, Tableau économique d’ensemble 2019 (compte de d’utilisation du revenu et compte de capital)

Final consumption expenditure

It covers “expenditure by resident institutional units on the acquisition of goods or services that are used for the direct satisfaction of the individual or collective needs of the members of the community. ” 27

It is mainly generated by households, and includes all goods and services purchased (excluding housing, which is considered an investment) as well as those produced for own final use.

This approach to household final consumption is rather restrictive, as it excludes expenditure that benefits households but is borne by public administrations (education, health, culture, etc.) or non-profit institutions (see box).

Companies (financial and non-financial) have no final consumption expenditure. Their purchases of goods and services are used either for intermediate consumption (in which case they are excluded from GDP), for compensation of employees in kind (in which case they are charged to household final consumption), or for investment (see below).

Calculating general government final consumption expenditure

As we have seen, public administrations produce non-market services for the rest of society. As these services are not sold and therefore not acquired directly by other institutional units, national accountants initially consider that this non-market production (NMP) is consumed by the GGUs themselves.

We then obtain their final consumption expenditure by adding: i/ the value of the PNM 28 and ii/ the expenditure incurred by the APU with market producers to pay for goods and services provided to households (reimbursements for medicines, medical appliances, medical consultations, housing assistance, etc.).

It is then divided into two main categories:

– individual consumption expenditure covers spending for which the beneficiaries can be identified. This mainly concerns NPS for health and education services, as well as payments to market producers.

– collective consumption includes PNM, which benefits the entire community (defense, police, justice, general administration, etc.) and is therefore not individualizable.

The approach is the same for non-profit institutions: their PNM is allocated to their individual consumption expenditure.

Gross capital formation (GCF)

GFCF is obtained by adding gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), changes in inventories and acquisitions less disposals of valuables (jewelry, objets d’art, precious stones and metals held as a store of value).

Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) is the name given to the productive investment made over the course of a year by the various economic players. It is made up of acquisitions 29 minus disposals of fixed assets (see box).

The different categories of fixed assets

Fixed assets are goods and services produced for use in production processes over the long term (more than one year).

They may be tangible (buildings, transport equipment, civil engineering works, machinery, information and communication technology (ICT) equipment, cultivated animal or plant biological resources) or intangible (software, research and development, intellectual property rights, acquisition of original recreational, artistic or cultural works). Durable goods acquired by households for their own consumption (household appliances, cars, TVs, IT equipment) are not included in GFCF but in final consumption. On the other hand, the acquisition of housing is counted in GFCF, as it enables households to produce “housing services” (via rental or own final use).

Source The list of fixed assets (and their evolution) can be consulted on the Insee website.

The boundary between investment (GFCF) and intermediate consumption is not set in stone

Intermediate consumption and investment both refer to goods and services used in the production process.

They differ in terms of time of use: in the first case, goods and services are entirely transformed or consumed during production; in the second, they are used over the long term.

As far as GDP is concerned, this distinction is of fundamental importance, since the value of intermediate consumption is deducted from production, whereas this is not the case for investment. However, the boundaries between these two concepts have evolved over time.

For example, the acquisition of military equipment 30 research & development services or software and databases was classified as intermediate consumption until 2014 (when the new European System of Accounts, ESA 2010, was implemented by the national accountants of European countries). Thereafter, these various items were classified under investment. This resulted, for example, in an increase in France’s GDP of around €46 billion in 2010. 31

GDP does not include consumption of fixed capital (wear and tear on machines, buildings and infrastructure).

GDP is supposed to measure value added, i.e. the new value created by production in a country. This is why the value of intermediate consumption is deducted.

By the same token, we should also deduct wear and tear on the stock of fixed capital (known as consumption of fixed capital – CCF). Machines, buildings and infrastructure deteriorate over time. Some equipment (especially ICT, software and databases) may become obsolete. All this represents a reduction in added value.

Consumption of fixed capital is, however, difficult to assess. Not all countries carry out this type of calculation, and those that do may use different methods. 32

It is therefore customary to use GDP as the key indicator, rather than NDP (net domestic product), even if the latter is also calculated by national accountants. 33 This means that the deterioration in fixed capital is not reflected, which is a problem, for example, when software and hardware purchases account for a large proportion of GFCF, as the lifetimes of these investments are short. GDP (which includes GFCF) can therefore grow faster than NIP, concealing the obsolescence of productive capital.

Calculating GDP by income

Finally, GDP can also be calculated as the sum of income distributed by producers during the production process.

Source Comptes de la Nation 2020, Insee, Tableau économique d’ensemble 2019 (operating account)

The table above shows that income from employee compensation represented 1,243 billion euros in 2019, or 57% of value added. They were mainly paid to employees by non-financial companies (814 billion), then by general government (297 billion).

GDP is calculated by adding :

- Remuneration paid by producers to employees (including employer and employee social security contributions) ;

- Other net taxes on production 34 paid by producers to general government;

- Gross operating profit (EBITDA), which corresponds to what remains for the producer once direct production-related expenses have been paid (wages, net production-related taxes and intermediate consumption). It is an indicator of the profit that producers have made from their activity. It is obviously particularly important for non-financial companies (NFCs), since EBITDA is their main source of primary income, unlike households (where the main source is labor remuneration) or public administrations (where the main source is compulsory deductions). EBITDA enables NFCs to meet obligations that do not arise directly from production (paying interest on loans, paying corporate income tax), to invest and to pay dividends to their shareholders;

- Mixed income”, which corresponds to income from sole proprietorships 35 . It is said to be mixed because it includes, on the one hand (and for the most part) the remuneration of the self-employed work of sole proprietors and, on the other, the “normal” profit (EBITDA).

Don’t confuse GDP with National Income

GDP allows us to see which players are responsible for distributing income from production. However, it does not tell us what income is actually received by the various institutional sectors. For that, we need to look at gross national income. This measures the sum of primary income (from production and property) received by residents, whether this income is generated by the national economy or by the rest of the world.

To calculate it, you need :

- add to GDP income received from the rest of the world: this mainly concerns remuneration paid to resident employees by non-resident units, and property income (interest, dividends, etc.) paid to residents by non-resident units;

- subtract from GDP income paid to the rest of the world (remuneration and property income paid to non-residents).

Find out more

- Should we believe statistics? Very good video by Olivier Passet showing the conventional dimension of GDP.

- La comptabilité nationale, Jean-Paul Piriou, La Découverte, 2019

- Detailed statistics on the components of French GDP can be found in the Tableau économique d’ensemble (TEE) available each year in the Comptes de la Nation published by Insee.

- Statistics on the main components of GDP on Eurostat

Equating GDP with a country’s power or wealth is misleading.

What does GDP say about a country’s power?

As we said inEssentiel 1, wars were a powerful gas pedal in the creation of GDP and its affirmation as an indicator of a state’s power, or at least its ability to mobilize its productive resources to assert itself in the “concert of nations”. What is the situation today?

A simple analysis of the ranking of states by GDP shows that this indicator is insufficient to reflect political power.

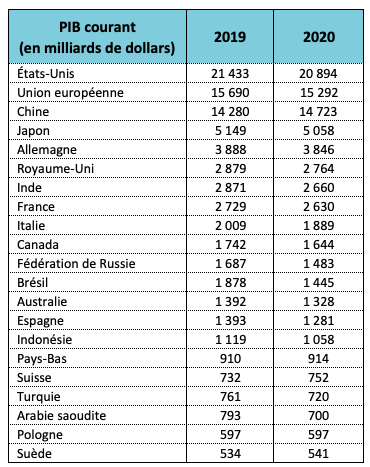

Consider the paradox of a geopolitically overpowered Russia, which in recent years has taken its revenge on the United States for the Cold War, but whose GDP is 50% lower than France’s (and whose per capita GDP is four times lower). Or, conversely, the European Union, which is still unable to influence the course of the world despite having a GDP equivalent to that of the United States and China.

Nor does GDP say anything about a country’s dependence on supplies from the rest of the world. This factor was particularly highlighted during the COVID-19 crisis, when globalized production chains were disrupted or even brought to a standstill, leading to disruptions in supplies of essential goods needed to respond to the pandemic (masks, paracetamol, test reagents, respiratory equipment, food production) or for the overall functioning of the economy (microchips).

The same applies to energy independence. It is invisible in GDP, even though we have known at least since the oil crises of the 1970s the extent to which energy is a determining factor in global production.

Finally, it’s important not to confuse a country’s economic power with the wealth of its inhabitants (measured by GDP, which we’ll see later is a very crude measure). The example of China is particularly enlightening in this respect. The world’s second-largest economy in terms of GDP, China has been enjoying growth rates that have Western leaders dreaming for decades. Does this mean that its inhabitants are among the richest on the planet? Certainly not. If we look at GDP per capita, in 2019 China ranked 79th if measured in constant dollars(see here) and 83rd in purchasing power parity(see here).

A country’s wealth is its heritage

As we saw inEssentiel 3, GDP is a measure of the value added generated in a given territory in a given year.

It is therefore first and foremost an indicator that measures a flow and not a stock of wealth.

It’s quite possible for a country’s GDP to grow year on year, then suddenly collapse because this growth was based on the exploitation of natural resources whose stocks have dried up. This is the well-known example of the island of Nauru after its phosphate mines were exhausted.

An individual’s wealth is not just his income, but also his assets (real estate and financial), his health, his knowledge, his know-how, his culture and the links he develops with others.

In the case of a country, heritage has many dimensions

Public assets are made up of financial assets and, above all, physical assets: infrastructure (water, electricity and telephone networks, roads and railways, ports and airports, etc.), community facilities, buildings housing public services (schools, hospitals, museums, barracks, etc.). Some of these assets, such as monuments and works of art, are not valued in monetary terms. Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris is worth nothing, and neither is the Mona Lisa, until they are put up for sale (to pay off the public debt, for example!).

A country’s heritage also includes its private production system: industries, agriculture and services. To what extent does an economy produce the food, clothing, basic materials (paper, steel, cement, etc.), medicines, energy, machinery, furniture, IT equipment consumed by its inhabitants? To what extent does it depend on global supply chains? Is our productive system capable of producing goods and services of interest to other countries, and does it therefore give us the financial means to acquire what we don’t produce?

Wealth also includes the institutions that enable the economy and, more generally, life in society to function: a judicial system, a police force, an army, a health system, an education system, and so on.

Finally, a country’s wealth is based on the natural heritage (public and private) that will enable future production. A more or less artificial national territory, a more or less rich terrestrial and marine biodiversity, forests, water tables, mineral and energy resources, living or dead agricultural soils, nature reserves, coastal areas.

In short, we are bequeathing more or less significant natural resource potential.

None of this is reflected in GDP: our economic system has reduced the notion of wealth to a very narrow dimension!

GDP is not a good indicator of economic and social health

Omnipresent in public debate, GDP and its growth are often equated with a measure of an economy’s economic and social health.

Yet as early as 1934, Simon Kuznets, the architect of American national accounting and inventor of GDP, warned against its use as an indicator of well-being 37 . The limitations of GDP as a tool for diagnosing the state of a society have since been the subject of a great deal of research.

Comme le résume très bien l’économiste Eloi Laurent, “le PIB est trompeur quant au bien-être économique, aveugle au bien-être humain et muet sur la soutenabilité écologique. La croyance dans la croissance est soit une illusion soit une mystification.” Nous abordons ici les grandes lignes des critiques concernant l’économie et les aspects sociaux et dans l’Essentiel 6 les critiques en matière d’écologie.

What does GDP tell us about a country’s productive structure?

As an aggregate indicator, GDP provides little information on the structure of production. On the other hand, going into more detail about the data used to calculate GDP provides access to a wealth of information.

For example, it is possible to analyze the formation of value added by branch 38 (agriculture, industry, construction, market and non-market services) or by institutional sector (households, financial and non-financial companies, public administrations, etc.).

Does this dive into the details of GDP provide an accurate picture of the balance of power within the economy and the evolution of the productive structure? Nothing is less certain. As we shall see from the three examples below, GDP seems less and less well suited to describing the evolution of a country’s economy.

Financial companies

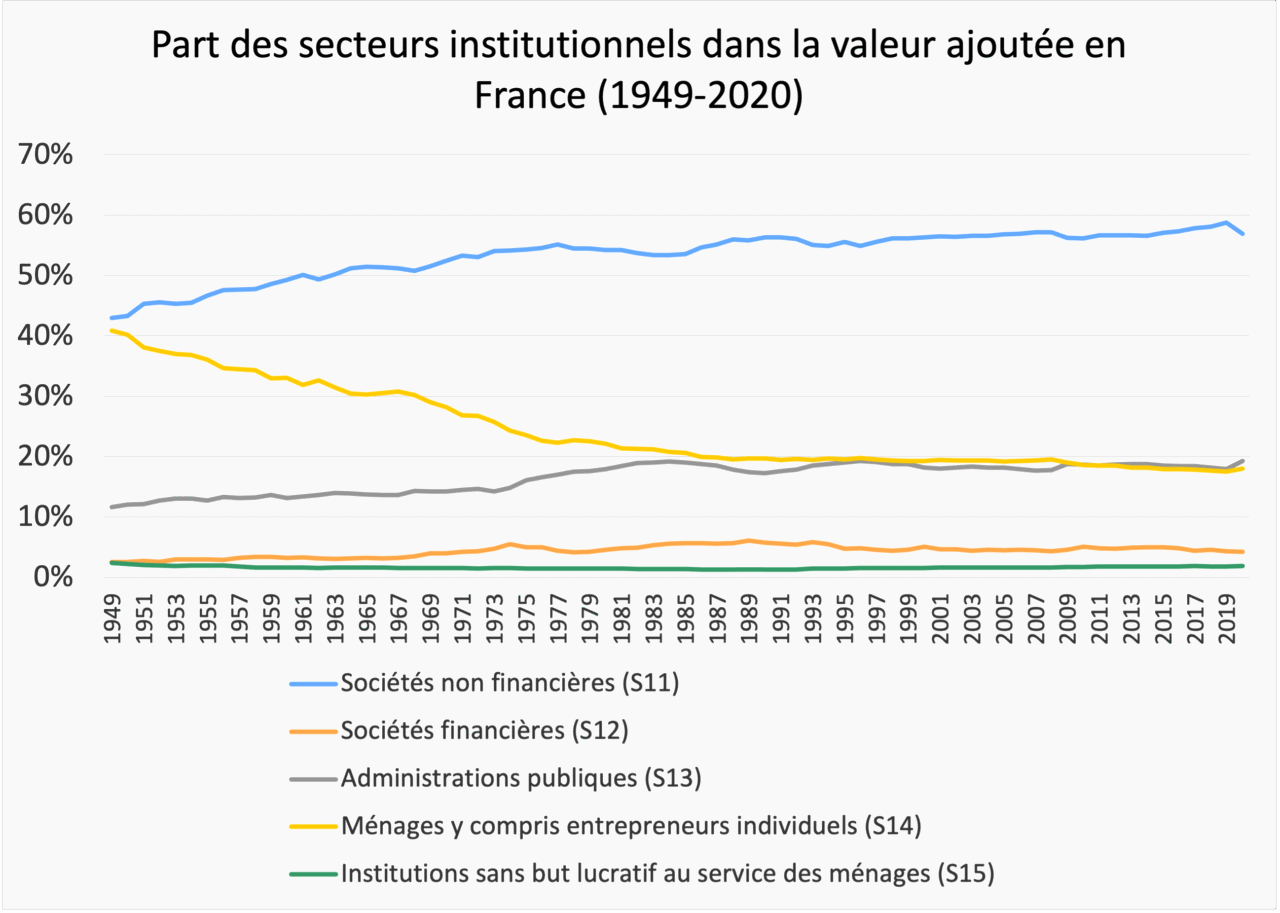

The following graph, for example, shows how little GDP reflects the rise of the financial industry since the 1970s. In France, the financial sector’s contribution to the French economy’s value added has hovered around 5% for 50 years, barely double that of associations. 39

GDP therefore completely fails to take into account the dizzying growth of the banking and financial sphere since the 1970s (see the Role and limits of finance module) and the growing power of these players over the productive sphere (see the Role and limits of finance module) and over public policy (see the Public debt and deficit module).

This situation is linked to the fact that the power of the financial industry is a consequence of the weight of financial assets, which is not reflected in GDP.

Institutional sectors’ share of value added in France from 1949 to 2020 (in %)

Source INSEE – National Accounts 2020 (Series 1.106)

The digital economy

The last decade has been marked by the emergence of the digital economy and its champions, the GAFAMs. 40 .

To date, the breakdown of GDP does not reflect this dynamic, as there is no “digital economy” branch in the national accounting classifications. The companies concerned are therefore classified in various other branches according to their main activity.

This situation is normal: statistical nomenclatures adapt with a certain time lag to changes in production structure. 41 . The current version of the System of National Accounts dates back to 2008, the year the first smartphone came out!

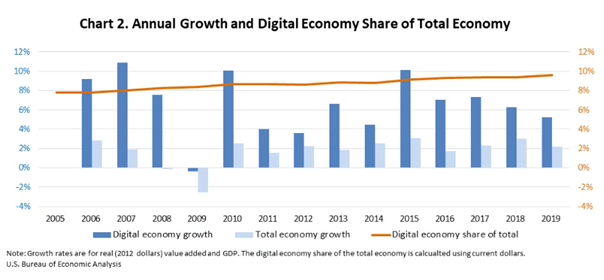

There are, however, a number of studies that attempt to assess the digital economy’s contribution to GDP. This is done, for example, by the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the United States.

GDP growth, growth of the digital economy and the digital economy’s share of GDP

Source Updated Digital Economy Estimates, Bureau of Economic Analysis (June 2021)

According to calculations by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the digital economy’s share of US GDP will have risen from just under 8% in 2005 to around 10% in 2019.

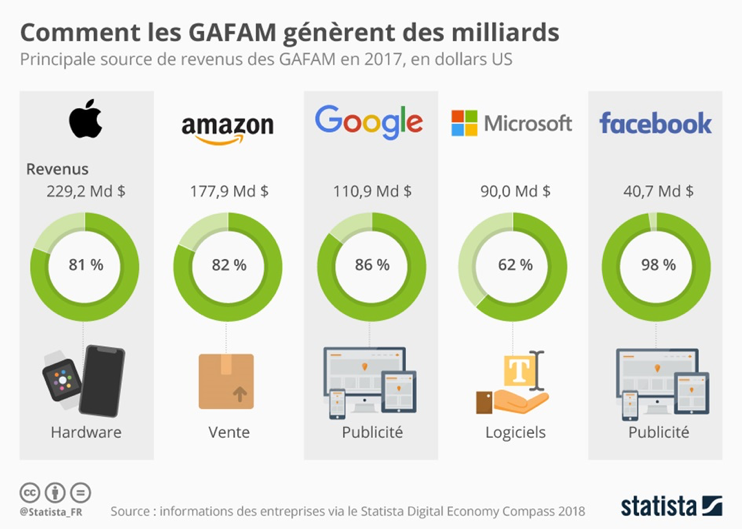

This work raises a number of methodological questions 42 that are far from being resolved. In particular, they come up against the fact that the power of digital companies, and in particular the GAFAMs, stems from a particular economic model: they provide “free” services, and in return capture and exploit the data of the users of these services. The primary source of revenue for Google or Facebook, for example, is advertising, whereas the real source of their power lies in their formidable capacity to capture data. This raises many questions that neither accounting nor GDP are able to answer today.

Source Les GAFAM, ces champions du numérique parfois compliqués à dompter, Cité de l’Economie (NB: in the above graph, revenue refers to sales).

The weight of multinationals

Finally, recent decades have been characterized by the emergence of multinationals. However, the national accounting system that has developed since the mid-20th century aims to track economic activity country by country, with GDP measuring production by resident units. 43 in each country.

As economist Jean-Paul Piriou clearly explains, this concept of residence “leads to neglecting the control exercised over certain resident units by resident units in other national economies. For national accounting purposes, IBM’s French subsidiary is part of the national economy (it is owned by IBM-USA, but its head office is in France), and Renault’s Spanish subsidiary belongs to the Spanish national economy. The residency criterion is therefore only partially realistic, as it does not allow for the integration of certain power relationships. Representing a national economy immediately makes it impossible to take into account the structuring of the global economy by transnational firms”. 44

Finally, the development of globalized value chains and the significant share of intangible assets (software, R&D, databases, brands) in production make it increasingly problematic to attribute production to a given territory. The example of Irish GDP is particularly enlightening on this point (see box below).

When Irish GDP surges, without associated production

“In July 2016, Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) revised the 2015 GDP growth rate sharply upwards, from 7% to 25.6% (CSO, 2016a). This upward revision was reflected neither in a similar revision of employment nor in physical capital accumulation. It is largely explained by the relocation, by a small number of large multinationals within their Irish legal units, of existing intangible assets (research and development, software, etc.), to the tune of 300 billion euros, rather than by the establishment of new production capacity.” This relocation was motivated by the particularly attractive tax conditions prevailing in Ireland.

In 2020, the problem persists. It’s the same type of phenomenon that gives the impression that Ireland has escaped recession, when in fact activity has been no more spared there than elsewhere in Europe. See Xerfi canal ‘s clear video on the subject.

Source Quote from L’énigme de la croissance du PIB irlandais en 2015 : tentatives de réponse, Économie et Statistiques, Insee, 2020

These various examples show the extent to which GDP seems less and less suited to fulfilling its original purpose: to measure the overall volume of a country’s production and to reflect the structure of production (by analyzing its components in terms of branches or institutional sectors).

For this reason, some national accountants 45 recommend moving from reporting GDP as an indicator of production to reporting GDP as a source of income (seeEssentiel 3). This would provide a clearer picture of what GDP measures, namely income flows that include revenues that can be extremely volatile (such as those linked to the location of intangible assets – patents, software, brands – of multinationals). However, this approach in no way resolves the question of power and power relations within the economic sphere.

GDP and well-being

It is undeniable that in poor countries, increasing the well-being of the population depends on increasing certain essential production (agricultural, industrial, health and education). More generally, economic growth conveys the idea of an increase in collective resources, and therefore in political and social room for manoeuvre, notably to improve people’s living conditions. As we shall see, however, the relationship between rising GDP and improved well-being is far from always proven.

GDP is not happiness: Easterlin’s paradox

Economist Richard Easterlin is credited with highlighting the paradox that bears his name. In a 1974 study 46 he compared the evolution of real income 47 and that of their “happiness” measured by declarative surveys in 19 countries for the period 1946 and 1970 (see box).

Its results show that, while richer people within a given country declare themselves happier than poorer people, this is not necessarily reflected by differences in income levels between countries.

On the other hand, in the United States, the 60%-plus rise in real income was not matched by a similar rise in the proportion of Americans who consider themselves “very happy”.

Subjective assessment of well-being

For some researchers, the concepts of quality of life or well-being are too subjective for objective indicators (i.e., based on physical data such as inequality, level of education or life expectancy) to achieve consensus. They therefore consider it preferable to rely on subjective indicators, based on people’s own opinion of their well-being.

These indicators are based on surveys of a representative sample of individuals, who are asked to rate their level of life satisfaction on a scale of 0 to 10 (overall, or in specific areas such as their financial situation or personal relationships). Conducted on a regular basis, these surveys enable responses to be compared over time (do people feel happier than before?) and between countries (where do they get the best scores?).

See, for example, the results of well-being surveys on the Eurostat website for the European Union, on the Insee website for France, and on the website of the Office of National Statistics for Great Britain. The Better Life Index, developed by the OECD, is made up of several subjective indicators.

This initial study has given rise to many others along similar lines.

Beyond a certain level, “more income” does not lead to “more satisfaction” or “more well-being”. An INSEE study conducted in 26 European countries shows, for example, that “rising living standards have a marked impact on life satisfaction up to 20,000 euros a year, which gradually fades between 20,000 and 40,000 euros. Beyond that, variations in living standards have a marginal impact on life satisfaction.” 48

GDP and social indicators

The “Trente Glorieuses” established the belief that GDP growth went hand in hand with improvements in a number of social indicators: job creation, reduced poverty and inequality, generalized improvement in purchasing power, higher life expectancy. Recent decades have shown, however, that such growth is by no means a sufficient condition for achieving these objectives.

For example, growth over the last few decades has not prevented mass unemployment from continuing in many countries, particularly if we consider the “unemployment halo”. 49 and not just unemployment in the strict sense.

GDP growth can be accompanied by rising inequality, as shown by the evolution of the Gini index in the United States, the world’s leading economy (see data on the World Bank website). 50 .

According to the OECD, “over the last thirty years, the gap between rich and poor has widened in most OECD countries, while the Gini coefficient has risen by three points, reaching an average value of 0.32”“. 51

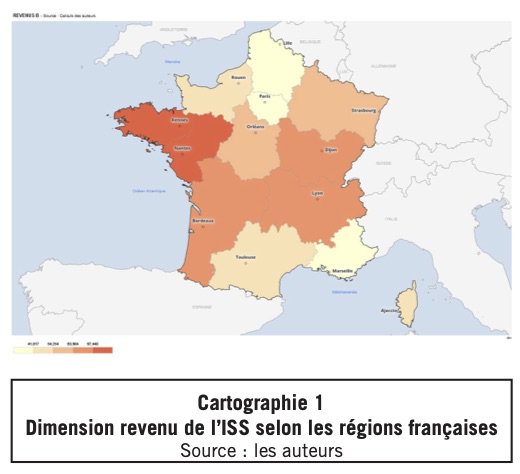

A high level of GDP per capita does not necessarily translate into better performance on social indicators (level of education, health, social ties, etc.). Research on French regions has shown that there is no correlation between GDP per capita and social health index (see box). Ile de France, the richest region, is also among the worst rated by this indicator.

The Social Health Index (SHI) for France’s regions

The SSI is a synthetic indicator that integrates six dimensions (housing, health, education, social ties and security, work and employment, income) through some twenty variables. For example, for education, the variables used are the rate of non-graduates and the rate of 18-24 year-olds who are neither in education, training or employment.

Source Florence Jany-Catrice, Grégory Marlier La santé sociale des nouvelles régions françaises et son évolution (2008-2016), 2020. Map interpretation: the darker the color, the higher the social health index.

As we saw inEssentiel 3, we decided not to include in the scope of production certain activities that we perform ourselves or for others without monetary exchange. Certain activities essential to the quality of social ties, such as voluntary work and domestic services, are therefore not included in GDP.

So, to increase GDP, it would be better to replace volunteers in associations with salaried employees; to put children in crèches and grandparents in retirement homes rather than have the former looked after by the latter; to buy ready-made meals rather than prepare them yourself; to pay for private lessons for your children rather than help them revise in the evening. Would it be better in terms of social health?

Finally, as we’ll see in the next section, over-exploitation of natural resources and pollution do not have a negative impact on GDP (on the contrary!), whereas the consequences of environmental degradation can be significant both locally and globally (via climate change, for example).

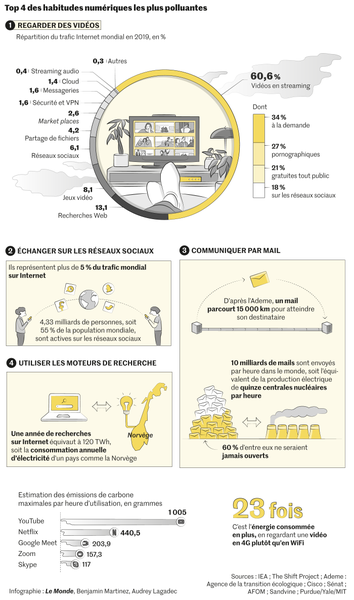

Growth in GDP goes hand in hand with growth in the exploitation and degradation of nature

One of the main criticisms of GDP is its environmental impact. Not only is GDP blind to the destruction of natural resources and major ecological imbalances, but the quest for growth also contributes to increasing them.

The dominant theories of growth generally focus on two factors of production: capital (in other words, all the equipment and infrastructure used by the economic system) and labor. They increasingly include “intangible capital” (inventions, patents, know-how), but “forget” natural resources (seeEssentiel 8 on macroeconomic models).

The reasoning behind this approach to growth is based on the idea that artificial capital (machines) could indefinitely replace natural capital. This approach, known as weak sustainability 52 However, it is clearly false: geo-engineering techniques will not replace natural climate regulation. 53 or bees and other pollinators by drones.

GDP is blind to the overexploitation of natural resources

It goes without saying that natural resources are the material and living foundation of all economic activity. We need water and arable land to raise livestock and grow food and textiles; wood and minerals to construct buildings, infrastructure and machinery; energy to heat our homes, cook our food, move people and goods, extract and transform matter and so on.

While the production and consumption process feeds on natural resources, much of it transforms them into waste and pollution (solid, liquid or gaseous) that is discharged into natural environments, disrupting and polluting ecosystems, turning the oceans into vast garbage dumps and destabilizing the planet’s climate.

Since the start of the industrial revolution, we’ve been drawing on the stock of natural resources, without GDP allowing us to see the limits. It’s simply not designed for this purpose: it only measures monetary flows generated by the production and exchange of goods and services.

We use water, soil, metals and energy, but the cost of building up these resources never appears on our bills. We pay only for the labor and rents involved in extracting, transporting, processing, marketing and advertising them, but never for the quantity of natural resources used, because Nature doesn’t charge for them…

What’s more, we benefit from a number of services provided by ecosystems (see the Economy, natural resources and pollution module) that are priceless in themselves. For example, we pay nothing for the water cycle, climate stability, the existence of an ocean conducive to life, photosynthesis or for the action of bees and other pollinators. Their disappearance, on the other hand, would have a very high economic, but above all human and ecosystem “cost”, of which we wouldn’t become aware until it was too late.

GDP is the driving force behind the destruction of nature

In addition to being blind to the dilapidation of our natural heritage, GDP and the quest for growth have until now been the driving force behind this destruction. When a primary forest is clear-cut, when a mine is put into operation, when industrial fishing fleets empty the oceans (while destroying the seabed), this generates jobs, goods and services sold – in short, GDP.

So, despite repeated warnings, global growth remains extremely well correlated with material and energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions and, more generally, pollution and the destruction of nature (to the point where it is probably the best indicator of this destruction!

However, natural resources are not inexhaustible, either because they are finite on the planet (such as fossil fuels or minerals) or because they are renewed too slowly in relation to the amount we take from them (fish stocks, soil, fresh water, forests, etc.) (see the Economy, natural resources and pollution module). This is what the inhabitants of the island of Nauru and the cod fishermen of Newfoundland have learned the hard way.

On the other hand, the activities required to repair the problems generated by economic activity (known as “defensive spending”), far from weighing on GDP, actually increase it: cleaning up beaches after an oil spill, or soils following chemical pollution, building wastewater treatment plants, building dykes to protect against the waters following the destruction of coastal ecosystems (mangroves, coral reefs), providing care to repair the health consequences of pollution… all this generates economic activity and therefore GDP.

But you have to have the means to pay to repair the damage, otherwise all you can do is endure it, as is the case for many populations around the world. And not everything can be repaired. While some of the services we derive from ecosystems can be artificially reconstituted (water purification, for example), this is not the case for most of them. It is impossible, for example, to replace the climate stability essential to human survival.

When the costs of repairing ecological damage become too great for the human economy, GDP will inevitably start to fall.

A few examples of the excellent correlation between GDP growth, natural resource consumption and pollution

Numerous studies based on physical reasoning have demonstrated the strong correlations between GDP growth, consumption of natural resources and environmental degradation.

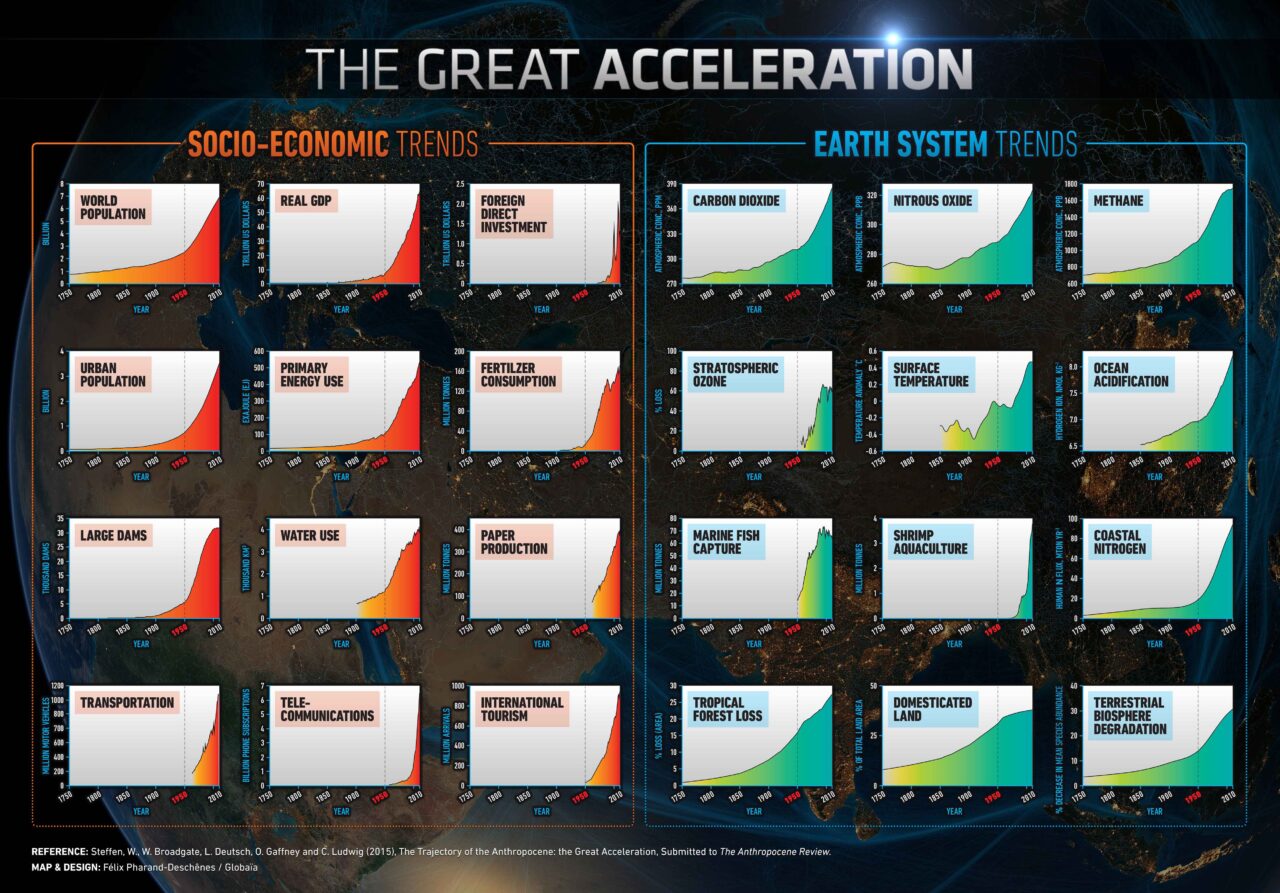

Researchers have highlighted the “great acceleration” of this process. 54 i.e. the exponential growth, from the 1950s onwards, of socio-economic indicators, foremost among which is GDP, and of indicators relating to resource consumption (water, energy, fish) and environmental degradation (greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, eutrophication of coastal zones).

GDP and natural resource consumption: the example of energy

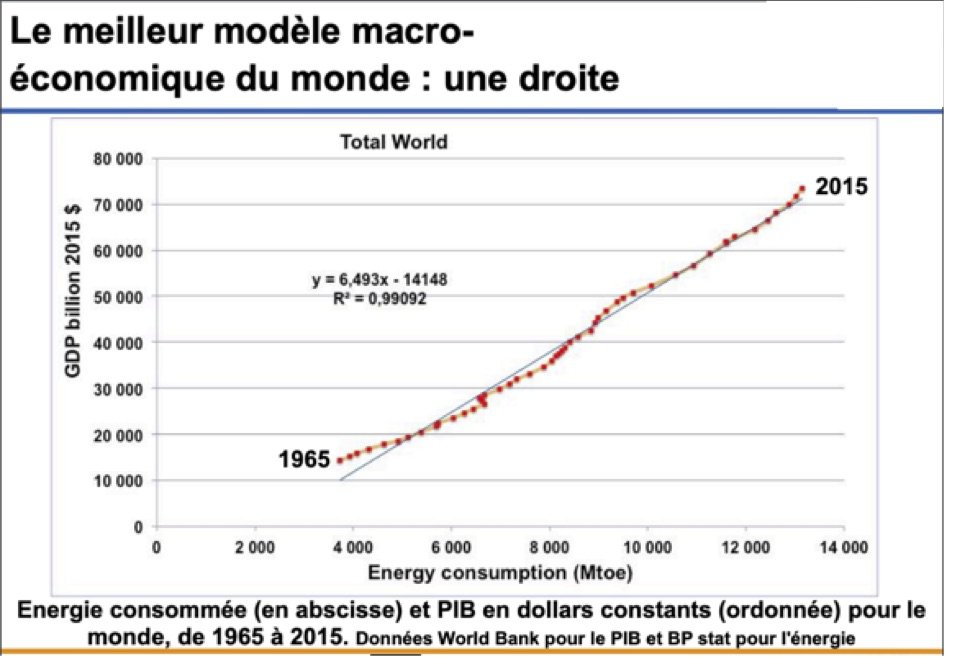

It’s easy enough to explain the correlation between economic growth and energy consumption. Economic activity consists mainly in the extraction and transformation of materials to produce goods and services consumed by human beings.

Among these materials, energy occupies a major place. Not only do we consume it directly (to heat buildings, move people and goods, cook food, operate electrical and electronic equipment), but it is also the driving force behind the transformation of other natural resources: all extraction and transformation activities require machines, and therefore energy.

Symmetrically, tensions over energy supplies at certain times (the 1973 oil crisis in the West being the most spectacular case in point) have led to lower growth rates.

The links between energy and GDP are not simply a coincidental correlation: there is indeed a causal relationship between GDP and energy. However, this relationship is not absolute. Rising energy consumption alone does not explain GDP growth.

In theory, while access to energy is key to “keeping our machines running”, and therefore the economy, it is not enough. We also need institutions, companies, knowledge, qualified and motivated personnel… to use and transform this energy.

Empirically speaking, some countries have (or have had) easy access to energy resources and have not seen their GDP grow. This is known as the “oil curse” or, more generally, the curse of natural resources. 55 Countries with substantial oil resources may fail to develop, either because of technical incapacity (this was the case for all countries in the world before the industrial revolution), or because of the capture of oil rents by an oligarchy.

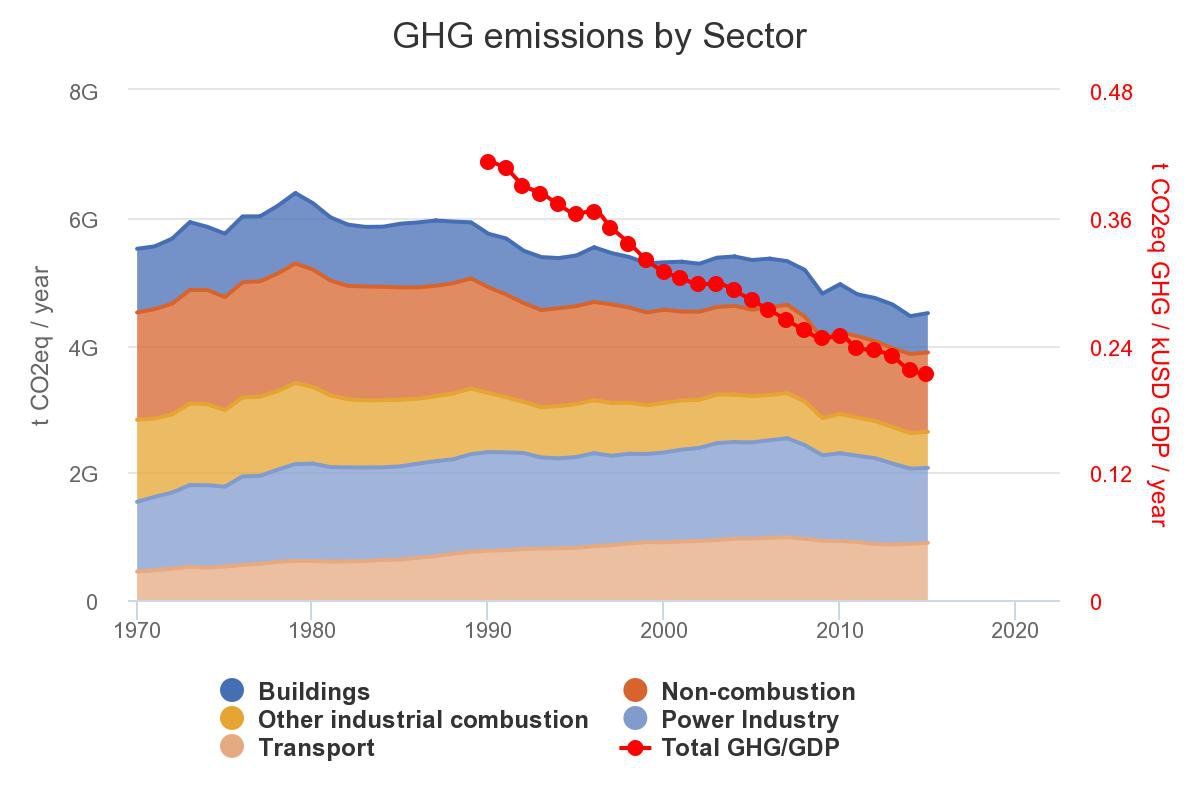

GDP and pollution: the example of GHG emissions

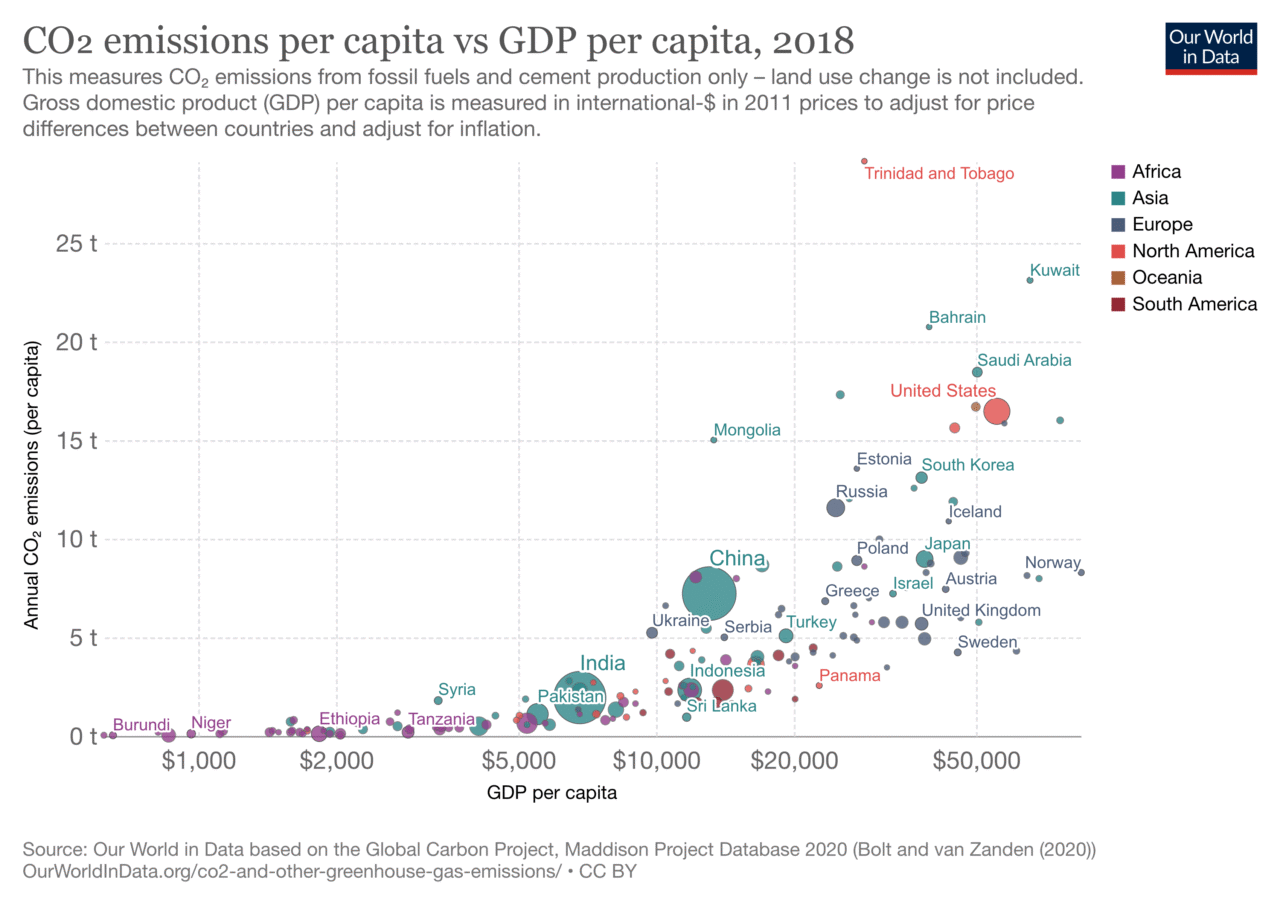

As the graph below shows, GDP per capita and CO2 emissions per capita are fairly well correlated. This correlation is obviously linked to the previous one (energy/GDP) insofar as the vast majority of primary energy comes from fossil fuels. Coal, oil and gas still account for 80% of the world’s primary energy sources.

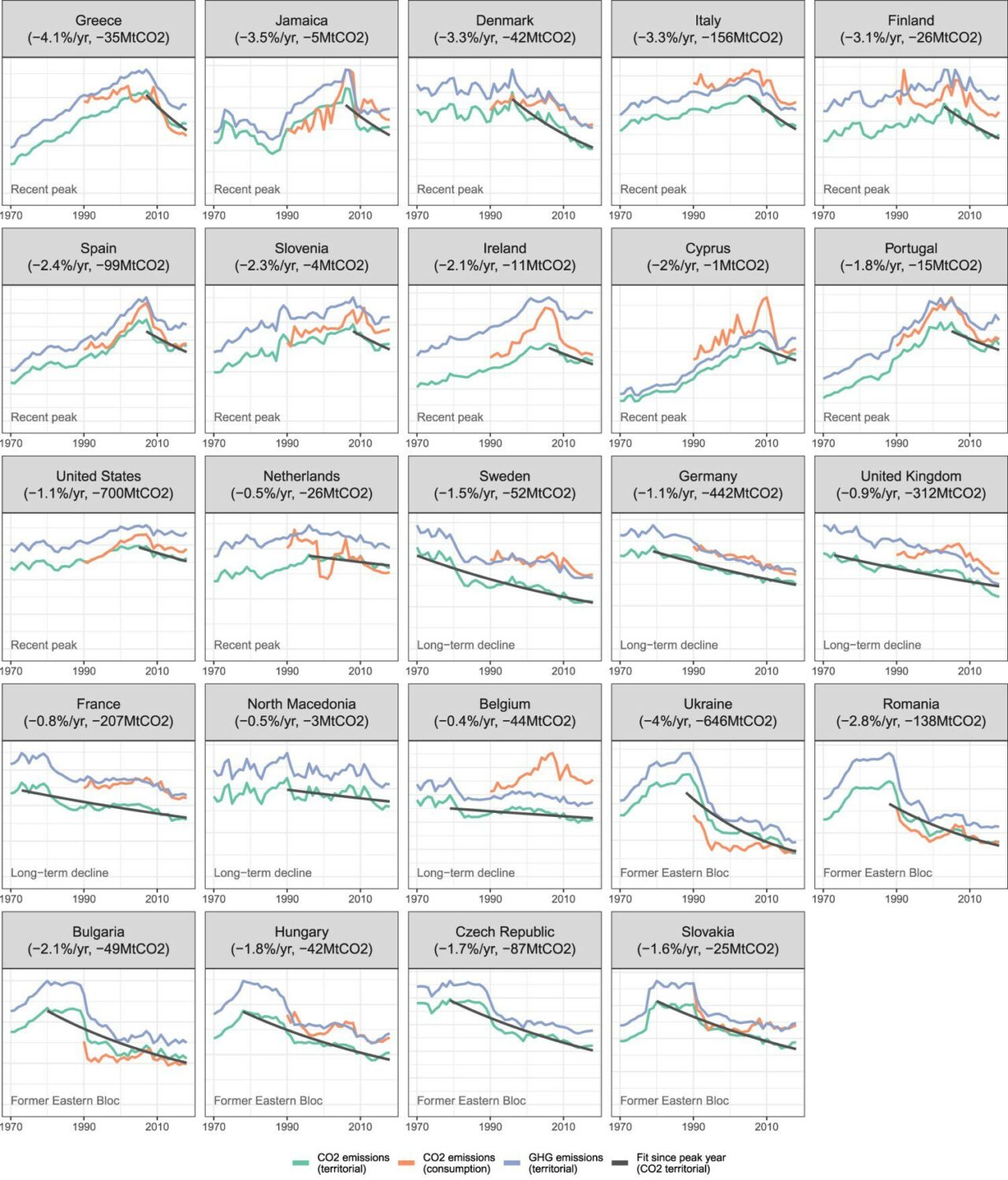

While a decoupling between CO2 emissions and GDP can be observed in some developed countries (seeEssentiel 9), the orders of magnitude are far from being right.

Find out more

- Eloi Laurent, Sortir de la croissance, mode d’emploi, published by Les liens qui libèrent, 2021.

- Tim Jackson, Prosperity Without Growth, Routledge, 2017.

- J. Stiglitz, A. Sen, J.-P. Fitoussi, “Report of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress”, 2009.

- Dominique Méda, Florence Jany-Catrice, Faut-il attendre la croissance, La Documentation française, 2016.

- “Towards a post-growth society?”, lecture by Dominique Méda, March 19, 2018.

- Vaclav Smil, Growth: From Microorganisms to Megacities, MIT Press, 2019.

The limits of GDP are well understood, but it is still far from being replaced.

As we saw inEssentials 4 and 5, the limits of GDP and the growth objective are now well established. Faced with these criticisms, national accountants and economists have come up with a simple response: GDP is not intended to measure the well-being, progress and, even less, the environmental sustainability of an economy. The indicator is not to blame for the media excesses and political veneration to which it is subjected.

For this reason, a great deal of work has gone into developing indicators to complement GDP, to put its use in public debate and public policy into perspective, and even to replace it. The ultimate aim is not only to provide other measures of the economy, but also to help shape other economic trajectories.

Alternative indicators to GDP

One of the fundamental debates at the heart of the debate on alternative indicators is whether or not to emphasize :

- a few synthetic indicators (see below) with sufficient communicative power to counterbalance GDP;

- or a table of economic, social and environmental indicators to provide detailed measurements of the evolution of society in its various dimensions.

Synthetic (or composite) indicators

Their purpose is to summarize various standardized variables in a single number. 56 which are then weighted and aggregated.

In addition to the often-present economic dimension, these indicators may focus more on social dimensions (e.g., variables on inequality, poverty and exclusion, social insecurity, etc.), or on environmental dimensions (e.g., variables on greenhouse gas emissions, material and energy consumption, land use, etc.). Some indicators aim to cover all these dimensions.

The main criticisms are that the choice of variables and, above all, their weighting are necessarily arbitrary, and that these indicators cannot of course cover all the dimensions of well-being and sustainability. Their promoters acknowledge these limitations, which are inherent in any aggregation procedure, but also insist that they have strong communicative power and are therefore good candidates to counterbalance the predominance of GDP.

A few examples of synthetic indicators

The Human Development Index (HDI) 57 is the oldest synthetic indicator. It is based on three criteria (per capita income, life expectancy and level of education) which are then weighted to give each country an overall score. Published since 1990, the resulting ranking differs widely from that of GDP per capita, although high-income countries remain at the top of the list.

The Better Life Index developed by the OECD as part of its Better Life Initiative, focuses on current living conditions and quality of life. Its main purpose is educational. It is based on 11 criteria 58 which are weighted at 1 by default. Users of the online tool can then vary these weightings and see how the country rankings evolve.

The Sustainable Development Index (SDI), developed by Jason Hickel, aims to measure the ecological sustainability of human development. The SDI takes the HDI (slightly revised) and divides it by an ecological overshoot indicator (itself calculated from the CO2 footprint and material footprint per capita). The ranking this time is very different from that of GDP/capita, with developed countries among the worst rated due to their excessive ecological overshoot.

Footprint indicators aim to measure the environmental impact of consumption by an individual, a country or a region (i.e., taking into account imports rather than just national production). The carbon footprint measures greenhouse gas emissions; the material footprint measures the quantity of materials extracted (biomass, fossil fuels, metals and non-metallic minerals); the water footprint measures the quantity of water used to satisfy a population’s demand for goods and services. The ecological footprint measures the productive surface area used to produce the natural resources consumed. 59 by a population and to absorb its waste (in particular CO2 emissions). These different indicators are then compared with the relevant planetary limits (for example, for the carbon footprint, the maximum level of greenhouse gas emissions per inhabitant to limit global warming to +2°C).

The report International Environmental Rankings, Ministry of Ecological Transition (2022) provides detailed information on 10 synthetic indicators.

Adjusted GDP” or “green GDP” is a special form of synthetic indicator.

Their purpose is to correct GDP by adding monetary estimates of activities that contribute positively to “present economic well-being” (leisure, domestic work) and subtracting activities that reduce it (commuting, pollution control activities, destruction of primary forests, etc.).

The advantage of these approaches is that they can be directly compared with GDP, and are part of a familiar measurement space: that of national accounts and the expression of values in monetary units.

On the other hand, they pose a number of problems: i/ they don’t take inequalities into account ii/ they involve giving a monetary value to goods and services that don’t have one, with all the methodological and ethical questions this raises, and, in particular, putting a price on nature iii/ they are based on a logic of weak sustainability: the destruction of natural resources can be compensated for by the development of artificial capital (machines).

These approaches have their origins in a 1973 article by Nordhaus and Tobin 60 which took very little account of environmental issues. Other examples include the genuine progress indicator and the sustainable well-being index.

Multidimensional dashboards

The most common approach at institutional level is to set up dashboards grouping together various unweighted indicators, either with a view to providing a global vision of the various dimensions (economic, social, ecological) of society, or with a view to informing specific public policies (education, transport, energy, etc.).

Multiple dashboards

The international community adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the 2015 United Nations General Assembly. This is broken down into 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), assessed by means of over 230 indicators. The SDGs are tracked in most countries around the world (at least those with a statistical apparatus): see here for France, here for the EU and here for the USA.

In the 2020 edition of its annual How’s life? report, the OECD presents an expanded dashboard of over 80 indicators of well-being (current and future). To make communication more concise, they have highlighted 36 key indicators 61 . Another example is the dashboard of green growth indicators.

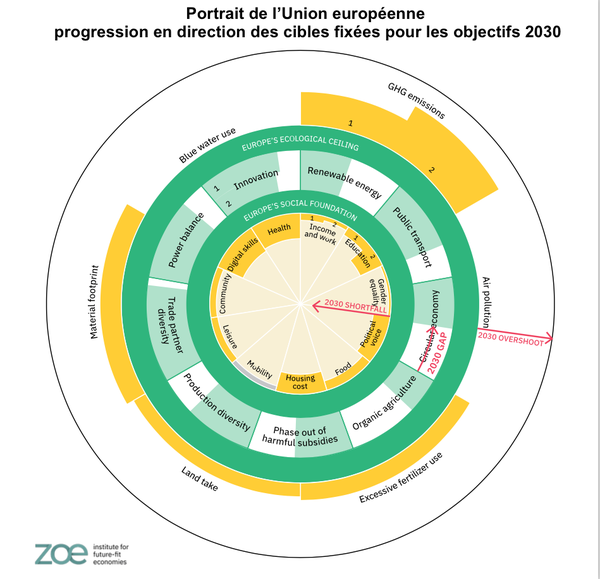

In a report published in 2021, researchers at the Zoe Institute reviewed the European Union’s multiple scorecards to analyze the coverage of social and environmental indicators. They counted over 450 indicators from 18 different political processes 62 . Their findings show that social and environmental aspects are rarely presented together. Above all, while these dashboards can be interesting for specific policies, they suffer from considerable fragmentation. They contribute to a siloed reading of different public policies, and are far from presenting an accessible synthesis, an overall vision, reducing complexity for decision-makers and civil society alike.

The value of dashboards lies in their ability to enable governments and experts to monitor and analyze in detail the various changes taking place in society. In addition, by using physical environmental variables, they provide warning indicators of the unsustainability of development.

However, these tables are extremely heterogeneous, making it difficult to select and prioritize the indicators they contain. Above all, they are poor communication tools.

“Public, political and media debate is largely dominated by economic and financial criteria: GDP, growth and stock market indices dominate the headlines and hold the audience record. They symbolize success. To organize public debates on how growth is or isn’t accompanied by social and environmental progress, with a powerful, well-known and much-publicized growth indicator on the one hand, and a table of several dozen variables on the other, is to place ourselves in a situation of unfair competition from the outset.”

A donut to replace dashboards?

Kate Raworth came up with the idea of representing humanity’s long-term goals in the shape of a donut. “Below the inner ring – the social foundation – lie critical human deprivations, such as hunger and illiteracy. Beyond the outer ring – the ecological ceiling – lies critical planetary degradation, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. Between these two circles lies the donut proper, the space within which we can satisfy the needs of all, within the planet’s means.” 64 This representation provides a general framework that underlines the need to balance environmental sustainability and social cohesion through a resilient economy.

The Zoe Institute has used this work as the basis for a visual representation of the European Union’s priorities between now and 2030.

Source Towards a thriving Europe beyond economic growth, 2021 Yellow areas above the ecological ceiling indicate transgression of ecological targets for 2030. Yellow areas below the social foundations indicate deviations from the EU’s social objectives for 2030. The green areas inside the “donut” represent political levers and economic tools.

How can we bring alternative indicators to GDP into the public debate?

Despite numerous studies on alternative indicators, we saw inEssentiel 1 that GDP and its growth remain at the heart of economic policy discourse and stated objectives.

In fact, it’s neither enough to measure alternative indicators, nor to proclaim them, to set in motion a profound social transformation. We also need to make them effective, in other words, to turn them into genuine tools for measuring and guiding public action.

Giving legitimacy to alternative indicators

A recurring demand of the promoters of alternative indicators to GDP concerns the modalities of their adoption. Since they are supposed to reflect the objectives a society sets for itself, it is necessary to give them legitimacy by initiating a public debate on what makes sense and the direction to take.

Make them genuine tools for guiding public policies

Public authorities need to get to grips with these indicators and make them operational. The general principle would be to justify the various public policy measures not because they are good for growth (or considered as such – seeEssentiel 2), but because they are beneficial to the ecological transition, to the reduction of inequalities, and so on.

The example of the SAS law in France is illuminating in this respect (see box): new wealth indicators are published regularly, but are not the subject of any specific communication and have no impact on public policy.

The failure of the French law on new wealth indicators