This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

For several decades, the obsession with fiscal discipline has been at the heart of public policy in Western democracies. Limiting public debt and deficits has become both the guide and barometer of public action.

The spectre of debt is thus mobilized to justify cuts in social spending, the necessary savings to be made in public services, and the impossibility of financing the ecological transition with public funds. The discourse is structured around moralistic maxims that seem to be common sense: just like a household, the State must manage its budget “as a good father of the family”. However, in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, this discourse was put in brackets: citizens were stunned to discover that it was possible to spend “whatever it takes” to support the economy.

In this module, we will focus on the extent to which this discourse is socially constructed, punctuated by numerous preconceived ideas that equate the State with a household and the public deficit with laxity. We will show that debt is the result of many factors, not only budgetary management, but also and above all public policy choices, debt financing methods and economic and geopolitical history. To meet the ecological and social challenges of the 21st century, it is essential to deconstruct the dogmas that today paralyze public action, and to understand the extent to which the State budget is a tool that can be mobilized both to respond to crises and to invest in the future.

Public debt, public balance, sustainability… Some definitions :

Public administrations (APU) include not only the State, but also various central government bodies, local authorities and social security administrations. Public debt is that of all these players, not just the State.

The public balance is the difference between government expenditure and revenue at the end of the year. This balance may be in surplus when revenue exceeds expenditure, or in deficit in the opposite case.

Primary deficit (or primary surplus) refers to the deficit (or surplus) before debt interest payments.

At present, general government finances its deficit mainly by borrowing:

– to financial markets by issuing negotiable debt securities (Treasury bills and bonds) (i.e., exchangeable between market players such as banks, pension funds, insurance companies, etc.). More details in Essentiel 3, on financing public deficits on the financial markets.

– a bank (especially in the case of local authorities)

– to other countries or to an international institution (such as the IMF): this is particularly the case for countries (such as Greece) that cannot access the financial markets because the interest rates demanded by investors are too high.

Public debt is the amount owed by public administrations to all their creditors, in whatever form (bills, bonds, bank credit, etc.) and at whatever time the debt was incurred. It is therefore a stock (unlike the deficit, which is an annual flow). See also our Measuring public debt fact sheet

Debt sustainability refers to a debtor’s ability to generate sufficient resources to meet its obligations to creditors (i.e. pay interest and repay principal).

Public debt should not be confused with national debt, which comprises the debt of all a country’s economic agents (public administrations, households, non-financial companies, financial companies), or with external debt, which is the debt owed by all a country’s agents to non-residents.

Find out more

This module was produced using the following sources

- La dette publique. Précis d’économie citoyenne, Les économistes atterrés, Seuil, 2021.

- Fiscal Mythology Unmasked, Finance Watch, 2021

- Benjamin Lemoine, L’ordre de la dette, Enquête sur les infortunes de l’État et la prospérité du marché, Editions La Découverte, 2016

- Expertise économique et politique publique: examen critique des propositions sur la dette liée à la pandémie, LIEPP Working Paper, 2020

- Teaching aids: understanding public debt – CGT – Pôle éco

The essentials

Managing the public debt and deficit is not a technical issue, but a major political issue

Managing the public debt and deficit is an eminently political issue, and not a simple matter of accounting, involving only technical variables such as interest rates, or the level of public spending and revenue. It is even less a question of managerial common sense and morality, as the many maxims that punctuate speeches on debt suggest.

The “danger” posed by public debt is based on a socially constructed discourse

Since the 1970s-1980s, the discourse of most Western governments has been marked by a dramatization of public debt. It’s a constructed narrative, a dramaturgy staged with selected sentences such as :

- “There’s no magic money” (see module on money),

- “Our children will be the victims of our debts” (Myth 1),

- misleading analogies between the State and households ( “debt can be repaid” – see Essentiel 2)

- arguments about the credibility of governments vis-à-vis financial markets. (See Misconception 3 and module on currency).

The academic argument is based on the public choice school of thought (see box below). As governments pursue their own interests (re-election), they are tempted to spend lavishly and let inflation run riot to ease social tensions. Fiscal policy must therefore be strictly supervised to counteract its negative impact on economic activity.

Public choice theory

It was in the 1980s and 1990s that the priority given to “sound” management of public finances returned to the political forefront. 1 . Its promoters can draw on the theoretical corpus of the so-called public choice school, whose ambition is to explain political behavior (of voters, elected officials, civil servants, interest groups) based on postulates derived from neoclassical theories (rationality of agents, methodological individualism, etc.).

According to this theory, governors, subject to pressure from voters and interest groups, would be unable to make optimal economic decisions. They would in fact be marked by a pro-deficit and pro-inflation bias, due to an incentive to satisfy voters in the short term by overspending at the cost of fiscal consolidation in the future (when they are no longer in power).

In practical terms, this means framing (or even removing) the two main tools of economic policy: the budget and the currency.

– The independence of central banks is seen as the institutional solution to the supposed inflationary bias of political decision-makers. In the eurozone, states have thus lost control of monetary policy, which is entrusted to the European Central Bank, legally independent of states and focused on the objective of controlling inflation. (This was not always the case: see “The institutional framework of money is not immutable”, Essential 2 of the module on money).

– The adoption of budgetary rules, defined via automatic debt and deficit indicators, makes it possible to exert a permanent constraint on fiscal policy and thus remove the question of deficit levels from political debate. In Europe, these are typically the 3% and 60% Maastricht criteria (see Essentiel 9, on European budgetary rules). The setting up of independent committees to monitor governments’ fiscal policies, and in particular debt sustainability, is also part of this logic.

Beyond academic publications, the discourse is legitimized by the multiplication of expert reports and independent committees which, on the basis of a selective diagnosis of debt sustainability (forgetting, for example, the question of public assets, dealt with in Essentiel 6), structure the field of possible prescriptions. These reports and the communication surrounding them enable governments to put forward a pseudo-scientific expertise, a so-called “consensus” which then invades the political, technical and media discourse, becoming a form of incontrovertibility.

Faced with the “risks” associated with public debt, public action is structured around an obsession with budgetary discipline.

All these factors contribute to making debt an external subject, outside the realm of political choice, irrespective of political “colors”. A permanent, and often self-inflicted, constraint to which governments have no choice but to bow.

At institutional level, the priority given to “sound” budgetary management has resulted in the silo organization of the various economic policy tools (currency, budget, financial supervision), making it very difficult to challenge and debate them democratically.

Current public action is organized in silos (Lemoine, 2016): we separate what comes under budget (the quest for a balanced budget), currency (apolitical control of inflation), and finance (preserving financial stability, the attractiveness of the Paris financial center and sovereign securities). A harmful consequence of this division of debt for the quality of the democratic framework is that it is largely accompanied by a depoliticization of decision-making in the field of public finance: these decisions are now taken by “committees of experts”, “wise men” or independent organizations (such as national or European central banks), which operate in a “confined” manner vis-à-vis society and outside any democratic process.

In terms of economic policy decisions, public action is structured around an obsession with budgetary discipline, and more specifically the need to reduce the weight of the bloated and expensive State, by cutting public spending.

At the beginning of 2021, in the midst of COVID 19’s economic crisis, Germany had already drawn up a repayment schedule for COVID’s debt, while the French government was considering how to repay the debt and opting for the hive-off route. 3 and reducing public spending over the long term through automatic rules.

This removes from public debate the fact that there is a diversity of economic policy choices.

“Restoring a balanced budget”, in particular by reducing public spending, is thus presented as the only possible option.

However, this is by no means proof of good policy. As explained in Essentiel 10, the public deficit is an essential tool for dealing with financial crises and recessions. This is how the mobilization of public budgets after the 2008 crisis helped to prevent the collapse of the financial system, and then to revive economic activity. In 2010, the self-imposed austerity measures taken by European governments did not obey any unavoidable economic constraint, and have had major ecological and social consequences (see Essentiel 12, on the negative impacts of “budgetary austerity“).

Choices in public spending

More generally, the amount and role of public spending are a matter for political and democratic debate. Is the priority to recognize the role of the State in investing in the infrastructures that will pave the way for the future (see Essentiel 11 and idée reçue 6), or to reduce public investment in the name of lower spending? How much of the risk of life’s hazards (loss of employment, illness, old age) do we want to mutualize via social insurance, and how much should be covered by private insurance? Should public services (water, energy, waste management, education, health) be managed privately or publicly?

All these questions are really about social choices that cannot be reduced to their accounting dimension alone.

Government revenue choices

What’s more, the budget balance is only a balance: it can be the result of quite distinct choices that concern not only spending but also revenues. The call to reduce the level of debt can, for example, conceal fiscal choices, reducing public revenues and then justifying spending cuts. Here too, democratic debate is essential. To what extent should we tax capital income, labor income, consumption, very high incomes, wealth and companies? What role should ecological taxation play? Is the tax system redistributive? How can we seriously combat tax optimization and fraud? Should the State promote the fight against tax havens on its own territory and at international level (or become one, as is the notable case of the Netherlands and Ireland within the European Union)?

Options for financing public deficits

Finally, the way in which deficits are financed is also a matter of political choice. Since the 1970s, the majority of Western democracies have opted for financing from the financial markets, which are supposed to exert a virtuous discipline on the management of public finances. In so doing, the financial players enter the democratic debate: public policies are subject to the dictates of certain economic standards, those that reassure creditors (see box).

Putting debt on the market subjects public policy to the judgment of actors with no democratic legitimacy

In chapter 3 of his book L’ordre de la dette, Benjamin Lemoine recounts the lecture tours that French Treasury officials made to the world’s major financial centers to sell French debt products.

Here, for example, is the list of questions likely to be asked by banks and investors prepared by the French Treasury in advance of a conference held in London in 1987: ” What is France’s inflation policy? Are labor costs rising in France? If so, by how much? Is it possible for France to leave the European Monetary System? How would you describe a “socialist” financial policy? What do you think of the Communist Party gaining enough support to share power? Will France give in to terrorism again? “.

At the conference held in New York in October 1987, JP Morgan, the host bank, presented a report detailing the economic fundamentals that made French public debt attractive to investors: “a free-trade economy”, “a non-inflationary policy stance”, “high unemployment” presented as a guarantee of “pressure on low wages” and “competitive labor costs”, “a tight and rigorous fiscal policy”.

Source L’ordre de la dette, Enquête sur les infortunes de l’État et la prospérité du marché, Benjamin Lemoine, Editions La Découverte, 2016

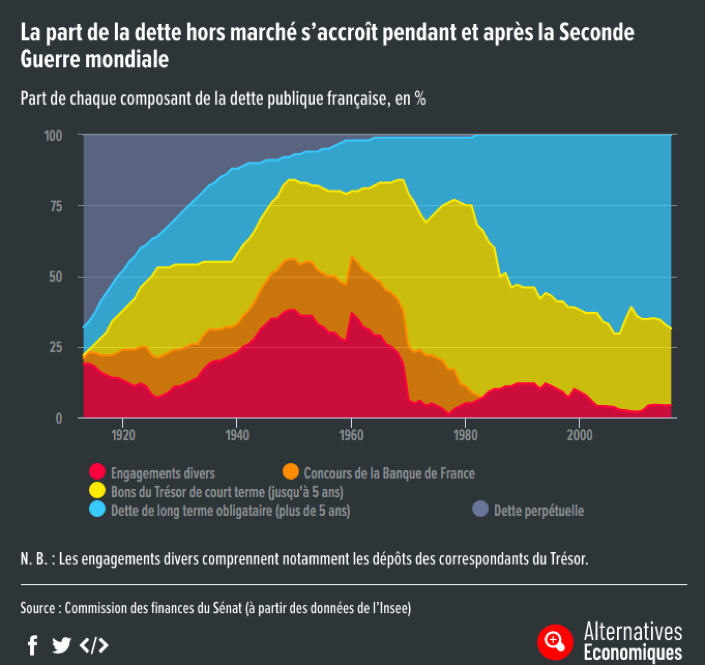

States have not always been so dependent on the judgments of financial players. In post-war France and during the Trente Glorieuses period, for example, a system of financing known as the “circuit du Trésor” was put in place, whereby many of the country’s financial resources were channeled into the Treasury, with the help of the central bank. In this system, finance was placed at the service of the State, rather than the other way round, as is the case today.

More fundamentally, monetary policy can be an economic policy tool for financing public investment. The sanctuary of this tool within an independent central bank focused solely on inflation control is the result of history (see module on money), not of unavoidable technical constraints (see also : Essential 5: “The explosion of public debt is linked to money creation mechanisms”).

The State is not comparable to a household or a company

One of the recurrent arguments used in discourse on public debt and deficit is to equate the State with a household or a company. This is the source of many preconceived ideas about “the debt burden we are bequeathing to our children” (preconceived idea 1), about the need to “manage the State’s budget like a good father” (preconceived idea 3), and about the fact that such and such a country is living “beyond its means” (preconceived idea 5).

As we shall see, while all these arguments make good sense when applied to a household or company, they are fundamentally flawed when it comes to the State (and more generally public administrations), as they amount to applying microeconomic reasoning to an actor with macroeconomic impacts.

Microeconomics and macroeconomics: definitions

Microeconomics studies the behavior of economic agents (households, companies, etc.) and how they coordinate on markets via the price mechanism.

Macroeconomics studies the economy as a whole, starting with the major aggregates (savings, investment, income, employment, GDP, etc.) and attempting to identify and model the relationships between them.

Macroeconomics cannot be reduced to the aggregation (i.e. addition) of economic agents’ behavior. In fact, macroeconomic phenomena can “emerge” from microeconomic behavior and produce results that are very different from what economic agents were initially looking for.

For example, during a recession, the rational response of households or companies is to tighten their belts. In so doing, their aggregate behavior leads to a reduction in aggregate demand (and therefore in orders for companies), deepening the recession. The macroeconomic result is the opposite of what each economic agent was trying to achieve (i.e. to protect itself against recession).

States are very special economic players

The link between the State and monetary policy

While most democracies in the developed world have chosen to entrust the management of monetary policy to an independent central bank focused on controlling inflation, this has not always been the case. Throughout history, central banks have regularly been much more closely controlled by the state, with the task of helping to finance public spending. Even today, some countries – China being the most notable example – retain control of their central banks and monetary tools, as we explain in the module on money.

This is obviously the first fundamental difference between the State and other economic agents (households, businesses).

States determine their own revenues by setting the level of taxation and, more generally, compulsory levies

Even if it cannot increase taxes without limit and without effect, this represents a first significant difference with economic agents whose financial resources depend mainly on “free” external decisions (customer purchases, employer decisions, etc.).

The State does not have the same time horizon as a household or a company

It doesn’t “die”. Unlike a company 4 a government cannot go bankrupt: it can default on its debt, i.e. it refuses or can no longer meet its debt repayments or interest payments. Creditors then have no choice but to negotiate with the state concerned.

As a result, a government’s ability to borrow and tax never, or very rarely, runs out. As a result, it can roll over its debt much more easily than a private player, and does not have to consider repaying it at a set term.

As long as it can find investors willing to buy its debt, the State can “roll it over”, i.e. borrow again to repay maturing loans. This can be seen in the graph below: for decades, many governments have been content to roll over their debt.

OECD Chart: General government debt, Total, % of GDP, Annual, 1995 – 2019

This doesn’t mean that increasing public debt is painless (Myth 2), just that equating the State with a company, and even more so with a household, is simply absurd.

State budget decisions have macroeconomic impacts

The decisive role of the State budget in an economic crisis

When economic conditions are bad, households in difficulty are forced to tighten their belts, while others tend, as a precaution, to increase their savings rather than spend; companies, seeing sluggish demand, are not investing; banks’ credit policy is also reserved.

All these behaviors point in the same direction: downward pressure on aggregate demand. Depression, then recession, set in and deepened. This phenomenon is all the stronger when private indebtedness is high, leading to the debt-induced deflation identified by Irving Fisher.

In such a situation, only the State can compensate for the drop in overall demand.

On the one hand, the State (and public administrations more generally) plays an important role in cushioning the shock of an economic crisis via “automatic stabilizers” (i.e., the automatic increase in certain expenditure linked to rising unemployment, social minima and falling tax revenues).

On the other hand, by implementing counter-cyclical stimulus policies (i.e. policies that move in the opposite direction to the economic cycle). 5 it can support demand and avoid catastrophic chain reactions.

Read more in Essentiel 10: “The public deficit is a tool for fighting an economic crisis”.

The decisive role of public authorities in investing and preparing for the future

The infrastructures and services enjoyed by a country’s inhabitants today are largely the result of past public investment: water, electricity and transport networks, healthcare systems, education systems, energy production, etc. The same applies to many innovations that were only made possible by public research. The same is true of many innovations that have only been possible thanks to public research. The example of the Internet, developed by the US military, is well known. More recently, the two innovations that enabled the rapid development of vaccines against COVID 6 came from American public research.

What was valid in the past is just as valid today. Coping with climate change and the collapse of biodiversity, while adapting our territories to the changes already underway, implies a profound transformation of our production system. To achieve this, the mobilization of public budgets is essential, as all the investments required to decarbonize our infrastructures, reduce our need for natural resources and reconvert entire economic sectors will not be financed by the private sector. And the investments needed for the ecological transition are massive: the European Court of Auditors estimated in 2017 that it would be necessary to invest at least €1,115 billion every year between 2021 and 2030, to meet the EU’s 2030 targets.

Read more in Essentiel 11: “Public investment in ecological transition takes priority over compliance with accounting ratios”.

Today, governments finance their deficits mainly on the markets

Since the 1970s, financing public deficits on the financial markets has become the norm. But it wasn’t always so. Let’s find out how it works.

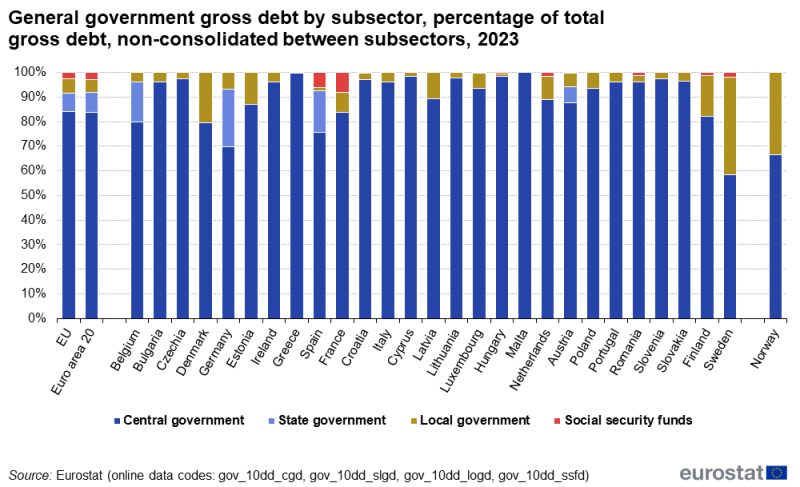

As we saw in the introductory definitions, public debt and deficit concern all public administrations, not just the State. For the sake of simplicity, however, we will concentrate here on the financing of governments, since government debt (or sovereign debt) makes up the bulk of public debt in most countries.

General government debt by sub-sector (as % of total debt)

Source Eurostat statistics explained – Structure of government debt

General government = administrations publiques; Central government = administration centrale (mainly the State); state government = administrations d’Etats fédérés; local government = administrations locales; social security funds = fonds de sécurité sociale (in some countries, the debt of social security administrations, when it exists, is included in that of other administrations, usually the State).

How can States finance their deficit?

State revenues are mainly made up of compulsory levies (taxes and social security contributions). The State also has non-tax revenues (sales of goods and services, dividends, fines, etc.), but these are marginal.

When government revenue is lower than expenditure, the government budget is in deficit, and must therefore find other financial resources. It can thus :

Through their central bank

Throughout history, central banks have regularly granted advances or loans (free or at very low rates) to their governments. Some still do so today (in China, for example).

From the 1970s onwards, however, this form of public financing was used less and less, until it disappeared in many countries on the grounds that it could have harmful consequences for price stability by triggering inflation.

Most states in the so-called developed world have thus abandoned the option of using their central banks to finance their deficits. This possibility was even banned in the European Union with the Maastricht Treaty (1992).

By issuing financial securities

The State may issue debt securities 7 (or public debt securities), known as Treasury bills or bonds, which are then sold to investors. See point 3.2 below for details.

Most of the time, these securities can be traded on a market, but this is not compulsory. For example, after the Second World War, France introduced a system known as “plancher des bons du Trésor”, which lasted until the end of the 1980s. Banking institutions were obliged to buy Treasury bills for a minimum amount corresponding to a portion of their customers’ deposits. The government set the interest rate.

Depending on international aid

Governments can also borrow from other countries or international financial institutions (such as the IMF). This mainly concerns countries that cannot, or can no longer, finance themselves on the capital markets: investors, considering their debt too risky, no longer want to acquire debt securities, or demand interest rates that are too high.

As part of their development policies, some countries can also obtain loans from multilateral development banks (such as the World Bank) or national development banks (such as the Agence Française de Développement).

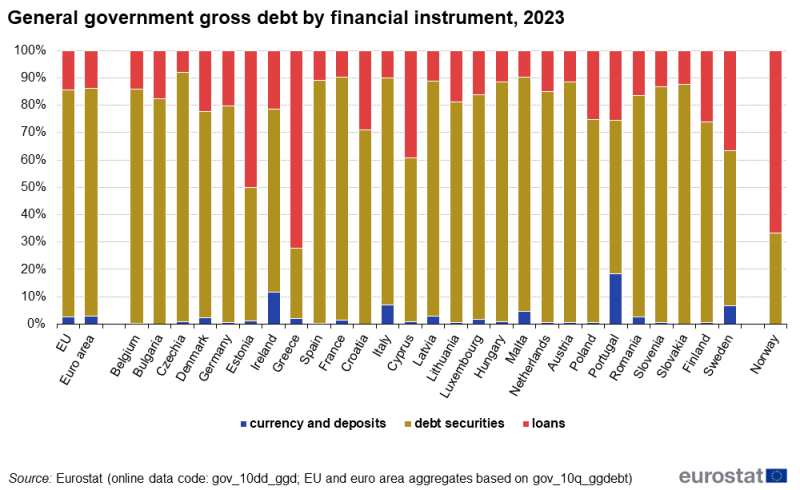

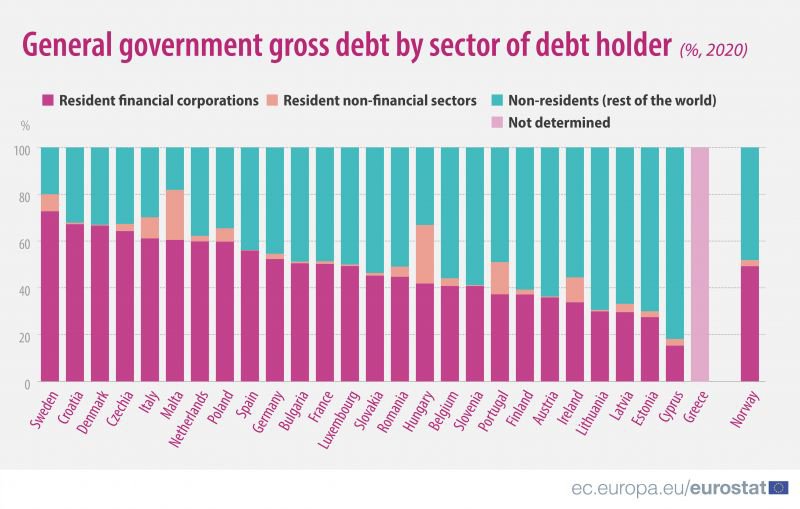

Around 80% of public debt in developed economies is in the form of debt securities

As the chart below shows,debt securities account for over 80% of public debt in the European Union. The orders of magnitude are similar in the other major OECD economies (Japan, United States, United Kingdom, Canada). Today, these securities are mainly used to finance public deficits.

Public debt by type of financial instrument in the European Union in 2023 (as a percentage of total debt)

Source Eurostat statistics explained – Structure of government debt

Note: ” Loans ” (i.e. non-marketable debt securities, bank credits and loans from international institutions) are significant in countries with low levels of public debt (Estonia), in those where local authority debt accounts for a large proportion of public debt (Norway, Sweden) and in those that have called on the assistance of international institutions such as the IMF (e.g. Greece and Cyprus).

What are the consequences of this predominance of negotiable debt securities?

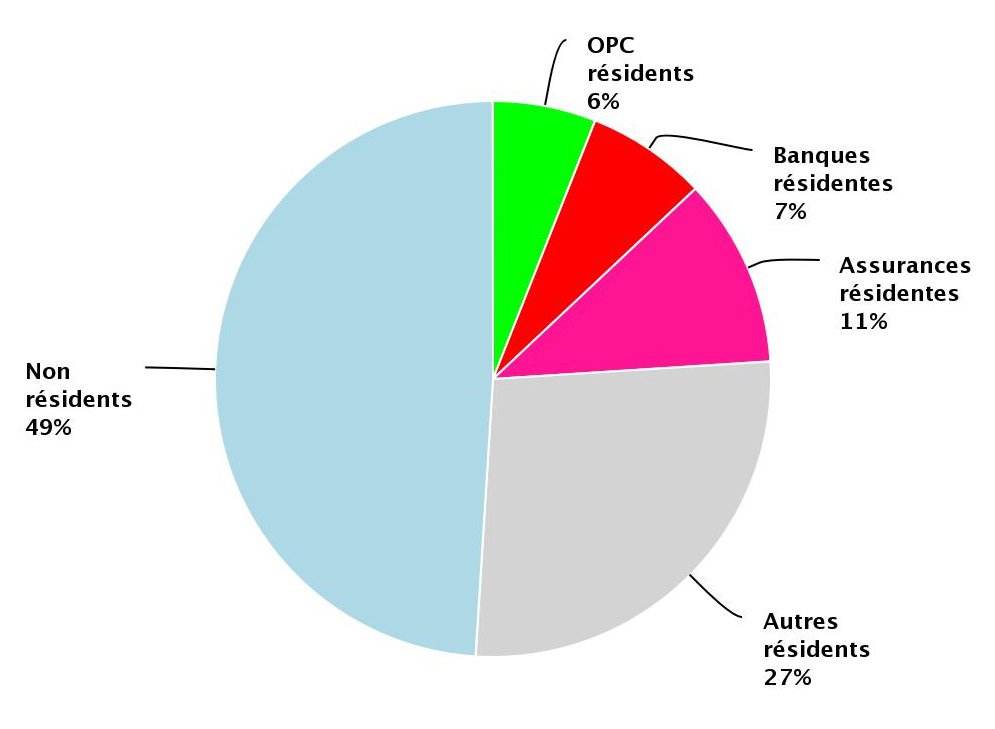

Let’s take the example of France to understand how securities are issued, how they are traded on the markets and what this means for public finances.

In France, Agence France Trésor (AFT), a public body under the aegis of the Ministry of Finance, is responsible for managing the government’s debt.

Note that debt securities can also be referred to as bonds or debt instruments (from the borrower’s point of view).

Treasury bills and bonds are issued on the “primary market”

Throughout the year, AFT issues various types of debt instruments, such as fixed-rate Treasury bills (BTFs) for short-term borrowing, and longer-term Treasury bonds (OATs). These debt securities are acquired by banking institutions (French and foreign) which have been granted a monopoly to purchase sovereign debt on the primary market (i.e. when the securities are issued). These institutions are known as ” Spécialistes en valeurs du Trésor ” (SVT).

The most widely used issuing technique is called auctioning, and is similar to an auction: the AFT announces how many bonds or bills it wishes to sell, and the primary dealers make bids, saying how many they wish to buy and at what remuneration (interest rate).

A debt security has three main components

> the amount lent, called the nominal or principal amount (e.g. €100),

> the maturity of the loan: treasury bills are debt securities redeemable in the short term (generally from a few weeks to a year) and treasury bonds are redeemable in the medium and long term (from 1 year to over 30 years).

> the interest rate (e.g. 2%), which is the borrower’s remuneration to the creditor.

Unlike an individual or SME borrowing from a bank, the issuer of a debt security pays only the interest each year. The principal is repaid when the bond reaches maturity. In the example above, the government has to pay €2 each year, and only repay the principal of €100 when ten years have elapsed.

Trading on the secondary market

The primary dealers can then resell these securities on the secondary market (basically the stock market) to other financial players (other banks, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds from other countries, etc.), who can in turn resell them.

When a financial player buys a Treasury bond or note on the secondary market, this does not bring any new resources to the French government. However, it does have an impact on interest rates on future debt instruments (see box).

How do exchanges of negotiable debt securities on the secondary market influence interest rates on public debt?

Let’s take our previous example: a €100, 10-year bond with an interest rate of 2%. The bond’s “nominal value” (i.e. the amount the government will have to repay) is €100.

On the other hand, its “market value” depends on demand: if many investors wish to buy this bond, they may be prepared to pay more than face value, say €120, to acquire the debt security concerned.

In this case, the bond’s yield decreases, since the interest rate paid by the government is still calculated on the bond’s face value. In our example, the bond’s yield will no longer be 2% per annum, but 1.66% per annum.

In concrete terms, this means that for the next issue, AFT should have offers for the same type of bond with an interest rate of 1.66% instead of 2%.

What are the consequences of putting public debt on the market?

The public debt market poses two major problems.

- On the one hand, the cumulative weight of interest payments can end up weighing heavily on public accounts (see Essential 5: “The explosion in public debt is linked to money creation mechanisms”).

- On the other hand, as noted in Essentiel 1, this gives financial players exorbitant power over governments. If the management of public finances does not meet their criteria for good management, they can demand higher interest rates and thus ultimately increase the cost of debt, or even prevent the State from financing itself if rates reach excessive levels. However, there is no guarantee that these criteria are in the public interest.

The central bank plays a decisive role

As we saw in 3.1, most governments can no longer rely on direct financing from their central bank. Nevertheless, the central bank has a decisive influence on public debt through the implementation of monetary policy.

Firstly, by setting its key rate, i.e. the rate at which it lends to banks, it influences all other interest rates in the economy (market rates, credit rates, etc.), including those on public debt securities.

In addition, and above all, following the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the central banks of the main currency zones gradually began buying up public debt on the secondary market (this is known as quantitative easing ). In so doing, they have made a major contribution to lowering interest rates on the debt of the countries whose currencies they manage.

These policies lasted until the COVID-19 pandemic, when they were further stepped up to enable states to cope with the economic crisis.

Find out more about the tools and mechanisms of monetary policy in the module on money and in our fact sheet on quantitative easing.

The example of the eurozone: in the face of crises, the European Central Bank has resorted to quantitative easing.

Eurozone countries are not entirely sovereign in monetary matters. The European Central Bank (ECB) is legally independent of governments, and is prohibited from lending directly to them (as are national central banks).

Until 2012, it refused to guarantee their debt. It therefore left the financial markets free to determine the cost. This is one of the reasons for the public debt crisis in the eurozone, during which interest rates in certain countries rose to levels where they could no longer obtain financing on the markets.

With this situation endangering the eurozone as a whole, the European Central Bank finally intervened.

In July 2012, ECB President Mario Draghi declared: “The ECB will do anything to preserve the euro, and believe me, that will be enough”, and launched a program to buy back the bonds of countries in turmoil.

Three years later, he went a step further by launching the first quantitative easing program. In concrete terms, this meant that the ECB (and with it, the national central banks) now assumed its role as lender of last resort to the eurozone countries. This guarantee “reassures the markets”. This is why investors have sometimes been willing to buy government debt at negative rates – in other words, to pay to hold government debt!

On September 5, 2019, France raised 10.14 billion euros, including 1.5 billion euros with a 15-year maturity. For the first time, the nominal rate at this maturity was negative (-0.03%).

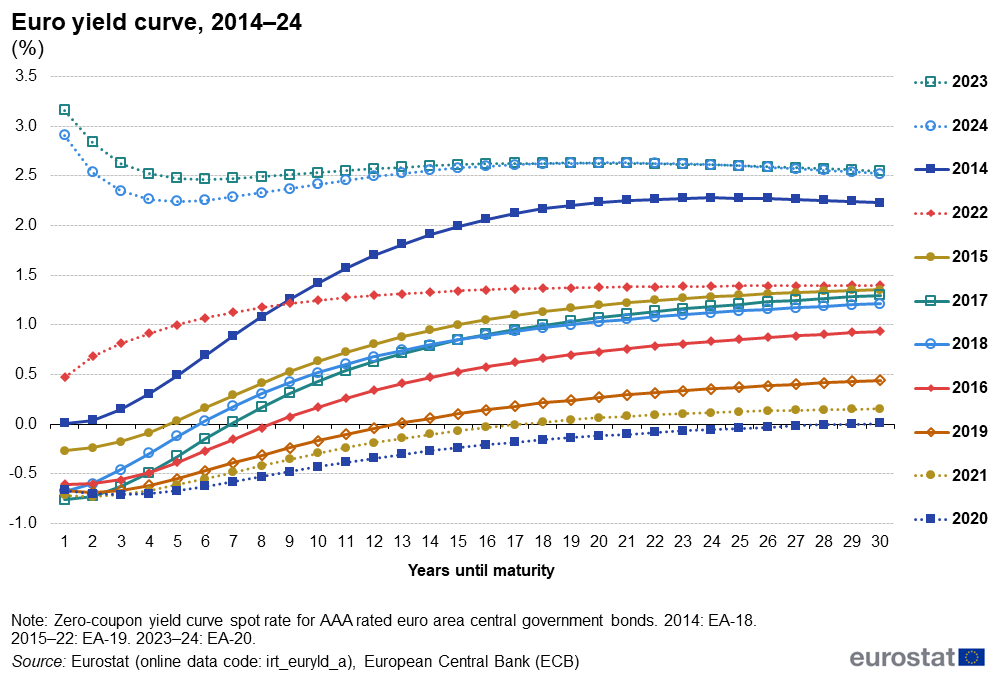

Yield curve for AAA-rated government bonds in the eurozone (2014-2024)

Source: Eurostat – Statistics Explained

Chart reading: in 2020 (dark blue dotted line), AAA-rated government bonds in the eurozone with a remaining maturity of 1 year (i.e. due for redemption in one year) had a yield of around -0.66%; those with a remaining maturity of 30 years had a yield of just over 0%.

Since 2022, the situation has changed. Faced with the inflation caused by the war in Ukraine (and its impact on a number of commodities, including energy), most central banks in the developed economies tightened their monetary policies (raising interest rates and ending quantitative easing). As can be seen from the diagram above, this has led to a rise in interest rates on government bonds.

Not all countries are equal when it comes to public debt

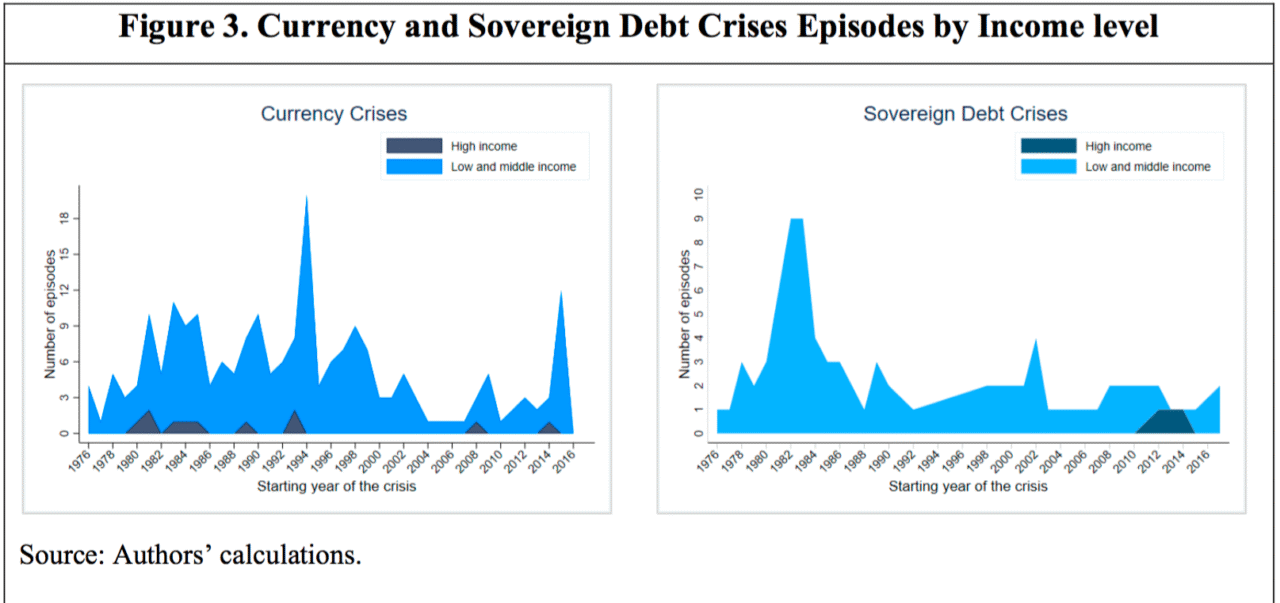

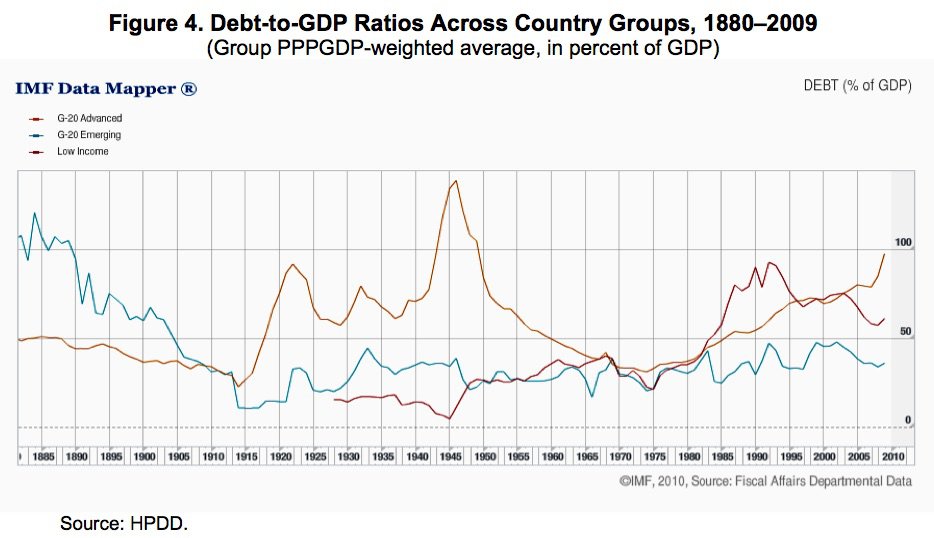

When we look back at the public debt crises of recent decades, we can see that they have been almost exclusively 8 in emerging and developing countries.

Currency crises and sovereign debt crises (depending on countries’ income levels).

Source Laeven, L. Valencia, F., ” Systemic Banking Crises Revisited ” IMF working papers p. 10 (2018).

The list specifying the years of crisis and the countries in which they occurred can be found in the appendix to the working paper (p. 30).

This is no coincidence, since, as we shall see, most of these countries do not have the option of incurring debt in their own currency.

A recurring current account imbalance (see box) can then lead to a public debt crisis. The following diagram explains the mechanisms involved.

Definitions: balance of payments, current account, trade balance, etc.

The balance of payments is a national accounting document that shows the annual balance of trade between all the economic agents of a country and the rest of the world. The balance of payments is made up of three main accounts.

The current account shows the balance of :

-trade in goods (balance of trade) and services (balance of services).

-primary income flows: wages (e.g. from a French resident working in a border country) or investment income (e.g. from a French company operating abroad that repatriates its profits to France).

-secondary income flows: international aid (e.g. grants from development banks) and remittances (e.g. immigrants sending money home to their families).

The capital account shows the balance of purchases and sales of non-financial assets (buildings, infrastructure, patents, copyrights, etc.).

The financial account shows the balance of financial flows between a country and the rest of the world (direct investment, portfolio investment – shares, bonds, etc.).

The current and capital accounts determine an economy’s exposure to the rest of the world. The financial account explains how it is financed.

By construction, the balance of payments is always in equilibrium (by adding up 9 all items, the result is always zero). For example, any deficit in a country’s current account (often linked to the fact that its imports exceed its exports) must be financed by borrowing, resulting in a surplus on the financial account.

A balance of payments crisis occurs when a country is unable to find the necessary financial resources to cover its current account deficit.

Source Find out more on the la finance pour tous website and on the Statistics explained website of the European Union.

Why do some countries have to take on foreign currency debt?

Many developing countries have current account deficits 10 . This means that imports and income paid to the rest of the world exceed exports and income received from the rest of the world.

This can be the result of imports of everyday consumer goods or durable goods not produced locally, or the employment of foreign companies to carry out infrastructure or construction work, for example. A current account deficit can also result from a sharp fall in world prices for the goods or services the country exports (or conversely from a rise in prices for the goods and services it imports).

In order to pay the companies concerned, public and private economic agents must do so in the currency they require. But not all currencies are equal: some, like the dollar, euro, pound and yen, are convertible. Others are not. This means that convertible currencies can be freely exchanged for any other currency in the world, but the reverse is not true (to find out more, see “Most currencies are non-convertible” in the currency module).

It’s easy to understand why a foreign economic agent would rather ask to be paid in dollars or euros than in Lebanese pounds, for example.

The public and private economic agents of the country in deficit must then obtain means of payment in foreign currency: they must borrow in a currency that is not their own.

Why public debt in foreign currency poses a double risk for governments

High interest rate risk

If creditors consider a government’s debt to be risky (i.e., they fear they won’t be repaid because of political or economic considerations, such as a recurring current account imbalance), they raise the interest rates they charge to lend to it.

This risk concerns all borrowers, but is less significant for countries that are able to borrow in their own currency, since they can benefit from the support of their central bank. 11 .

Furthermore, countries unable to borrow in their own currency are dependent on the monetary policy decisions of the country issuing the currency in which they are indebted. This is what happened, for example, to Latin American countries in the 1970s and 1980s. Heavily indebted in dollars, they bore the full brunt of the rise in international interest rates following the decision by the US central bank (the Fed) to raise its key interest rates from 1979 onwards. 12 .

Foreign exchange risk

A country with a structural current account deficit runs the risk of seeing its currency lose value against other currencies. 13 since it is less and less in demand on the foreign exchange market. Indeed, since the end of the Bretton Woods Agreement in the early 1970s, the international monetary system has been characterized by floating exchange rates (see the module on currency): this means that currencies move freely against each other according to supply and demand. The value of foreign debt (and interest) rises when expressed in domestic currency, without the government even having to borrow again.

When the time comes for a country to repay its debt, it is no longer in a position to “roll it over”, i.e. to borrow again to pay what it owes its creditors. It may then find itself in default, and must negotiate with its creditors or their representatives (IMF, Paris or London Clubs), often agreeing to painful “structural adjustment plans” (see Essentiel 12) designed to restore balance to public accounts.

The surge of public debt is linked to money creation mechanisms

The link between money creation and public debt is obvious in theory: if the State benefits from money creation, it does not incur debt to match. And it is the only actor with the legitimacy to do so. This is known as “monetizing public debt”.

As we shall see, this practice is now prohibited, condemning governments to submit to the “whims of the markets”.

Money is created by banks when they grant credit.

The monetary system in force in a country or zone is closely linked to the legal framework that guarantees the payment system and determines the role of the various institutions in charge of creating and circulating money: central banks and second-tier banks. 14 . It is the result of the history and specific features of each country or monetary zone (more on this in the module on money).

Since the 1970s, the dominant system in most of the world’s major economies has been based on money creation by secondary banks when they grant credit (more on money creation in the Money module). Central banks also create money, but this is only used by secondary banks, not by other economic agents. In particular, central banks are prohibited from 15 from directly financing governments, whether through loans, advances or even grants.

Financing deficits on financial markets increases public debt

Since public money creation is forbidden, governments have no choice but to finance themselves on the financial markets, and thus pay the interest rates demanded by creditors.

This situation is legitimized by the doctrine that the State must submit to market discipline (see module on money) and by the preconceived notion that public debt is the result of States’ lax fiscal policies. By being obliged to borrow from the market, the State would have to justify its sound budgetary management. Conversely, recourse to money creation by its central bank would allow it to take advantage of “anti-economic” facilities.

The stakes are high. Because of the snowball effect, as soon as the interest rate is higher than the growth rate, public debt increases mechanically, unless the State generates sufficient primary surpluses.

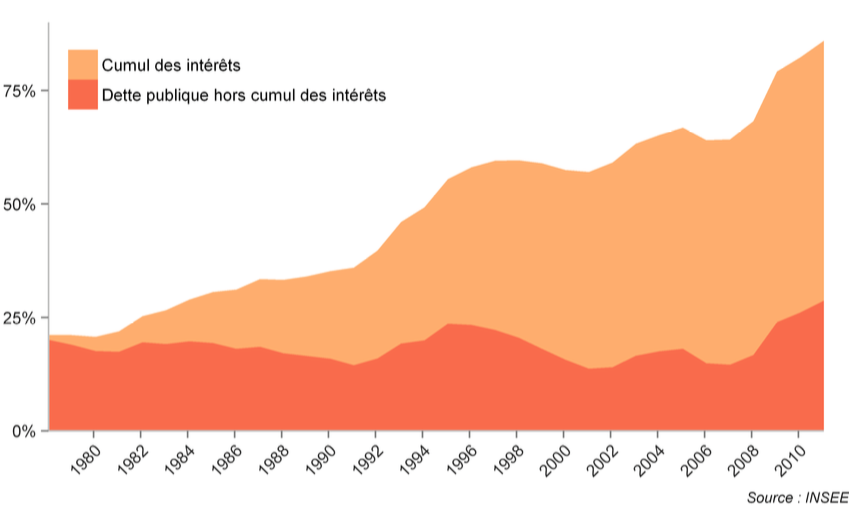

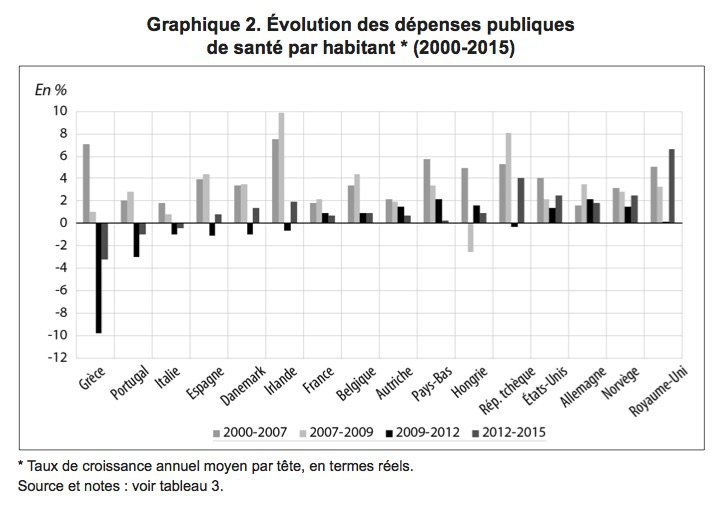

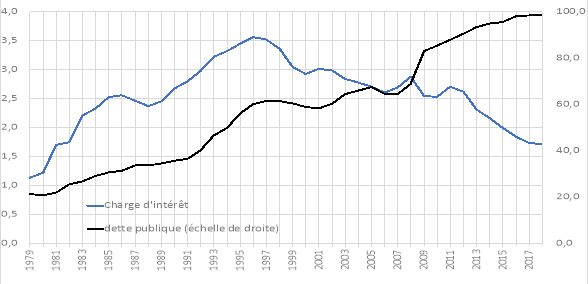

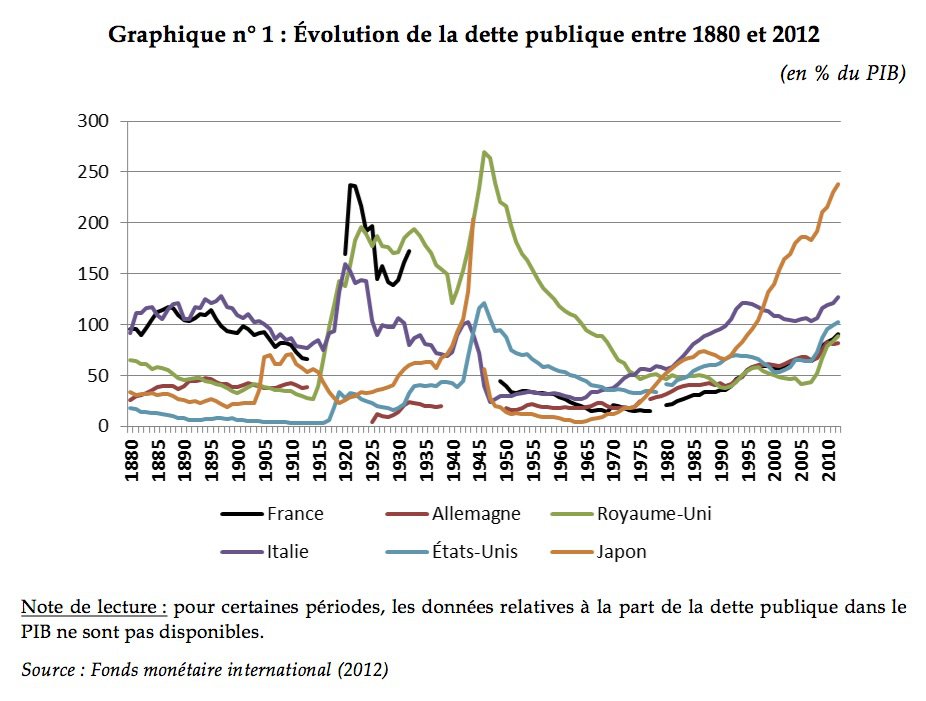

In a 2012 article 16 Rossi Abi-Rafeh, Gaël Giraud and Florent Mc Isaac analyzed the evolution of French public debt from 1980 to 2011: from around 25% of GDP in 1978 to 86% in 2011. The authors break down this debt into what is due to interest payments and what is due to the primary deficit (i.e. before interest payments).

They conclude that “if the French state had taken on debt at zero interest, our gross public debt today would have been 28.5% of GDP in 2011 (instead of 86%), all other things being equal.” Put another way, if the State’s financing needs had been met by money creation without debt and without interest, then France’s public debt ratio would have been stable overall.

Weight of debt servicing in French public debt – 1978-2011.

Source Rossi Abi-Rafeh, Gaël Giraud, Florent McIsaac, “Does French public debt justify fiscal austerity?”, 2012.

The first negative consequence of financing the State through debt is that the burden of interest payments falls on the public accounts. The higher the interest rates, the greater the amounts payable.

One might think, then, that the amount of public debt is not in itself a problem. 17 as long as interest rates are low. Put another way, since the sustainability of public debt depends first and foremost on interest rates, there would be no point in resorting to monetization when interest rates are low.

This analysis is not very convincing. On the one hand, it is not necessarily economically desirable for interest rates (which are not only used to finance public debt, but are passed on throughout the economy) to be zero – depending on the context. What’s more, their level can vary: there’s no guarantee that they won’t rise. If it does, interest charges will once again weigh heavily on public accounts. It’s a sword of Damocles. Finally, public debt as a percentage of GDP is perceived by the vast majority of citizens as a major economic constraint. Even if this is a belief rather than a truth, it must be taken into consideration when choosing options.

Opposite the public debt, there is a heritage

The dominant discourse on public debt is often marked by comparisons with household or corporate debt. “The State is living beyond its means”, “its debts must be repaid”, the State budget must be managed “as a good father of the family”… all recurring maxims that make the State appear to be something it is not, namely a microeconomic agent (see Essential 2 “The State is not comparable to a household or a company”).

While this comparison is developed when it is to the detriment of the State, it stops when it could be to the State’s advantage. In fact, an essential fact is overlooked: in the face of debt, there is wealth. Would we consider analyzing the financial situation of a household or a company by looking only at their debts and forgetting what they own? Yet this is exactly what is done for governments (and public administrations in general).

This is obvious in political discourse: never do those who invoke the spectre of public debt confront public assets. It’s also obvious when you visit the websites of statistics producers: data on public debt and deficit are immediately accessible. 18 but it takes a long time to find data on public assets.

French public assets exceed public debt

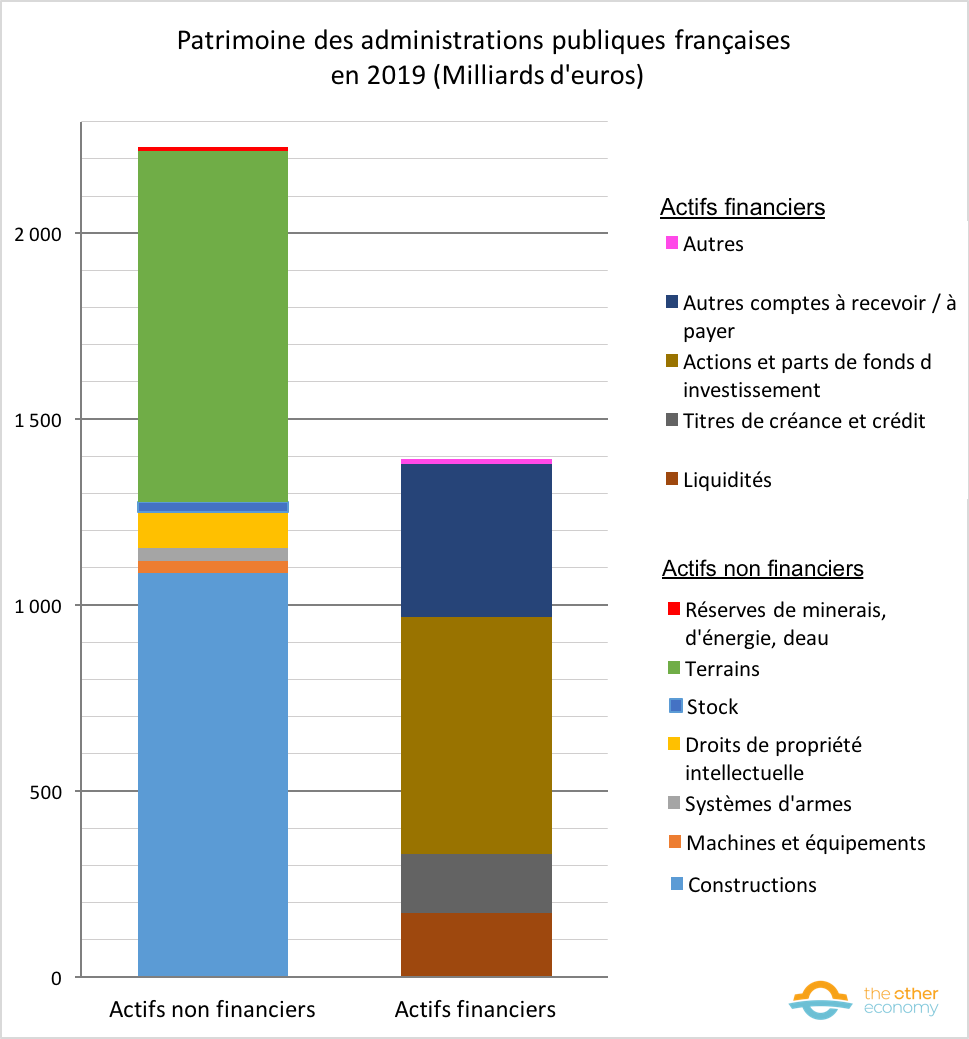

And yet, just like companies and households, public administrations have monetized assets to match their debt (their liabilities). This is made up of :

- financial assets (shares and units in investment funds, debt securities, loans, cash and deposits);

- non-financial assets: buildings, land, buildings and equipment resulting from past investments.

Insee thus estimates French general government assets at €3,626 billion in 2019, including €2,234 billion in non-financial assets.

On the other hand, gross debt 19 amounted to 3,312 billion euros, for net assets of 314 billion euros.

Depending on the statistical institution, the items included in the debt perimeter will not be the same, or will not be accounted for in the same way. This is why you need to be careful when making historical or cross-country comparisons: the calculation of public debt (see our fact sheet) can change over time and space.

Source Insee – Comptes de la Nation 2020 – Série 8.204 General government assets account

Moreover, this valuation of public assets considerably underestimates the assets de facto held or controlled by public administrations.

- It excludes undeveloped or unexploited natural areas and historic monuments. 20 and works of art, which are conventionally counted at 0. These elements are difficult to estimate, and sometimes of inestimable value. How can you put a price on Mount Sainte-Victoire or the Pointe du Raz? They do exist, however, and represent real wealth (even if not monetized) and, from a strictly financial point of view, are a source of revenue (if only for tourism) for the country and the State (via taxation at least). See our Infosheet Faut-il donner un prix à la nature?

- It excludes the intangible value of quality infrastructure, healthcare, education… all elements that make up a country’s quality of life, and for which citizens are willing to pay taxes… and companies to set up there.

Lack of data endangers public heritage:

>This contributes to the general dramatization of public debt. In addition to the debate on how to reduce debt, it would be interesting to have a debate on how to increase public assets.

>Data on non-financial public assets are extremely incomplete for most countries, or even non-existent altogether.

This can be seen from the Eurostat and OECD databases. Moreover, the methodologies used, even in the case of France, one of the countries that provides the best information on these elements, are questionable and have not changed for decades. 21 . This feeds a vicious circle: how can we discuss heritage, its conservation and its increase if we don’t know how to evaluate it?

>Finally, since the debate on public assets is of secondary importance to that on debt, it may be tempting to liquidate public assets in order to pay off the debt.

The privatization of public companies is part of this logic, even though these companies are particularly profitable (as in the case of French airports or La Française de Jeux) and therefore provide regular income for the State. This is even truer when it comes to works of art or architectural heritage. This is what happened in Greece, for example, which, to meet the demands of its creditors, put up for sale 22 beaches, islands, airports…

Find out more

Statistics on general government assets.

- France: Les comptes de la Nation – Comptes de patrimoine (series 8.204 for long data on general government assets)

- OECD – Table 9B. Wealth accounts for non-financial assets (sector: general government)

- OECD – Table 720. Financial balance sheets – non-consolidated – SNA 2008

- Eurostat – Non-financial balance sheet (table NAMA_10_NFA_BS)

- Eurostat – Financial balance sheets (table NASA_10_F_BS)

One man’s debt and deficit is another man’s savings and surplus.

We’re developing the argument here with regard to the financial balance (i.e. deficits and surpluses), but it’s just as valid with regard to debt and savings. In fact, it’s a simple arithmetic fact.

Each of the various institutional sectors (see box) has financial flows with the others 23 . For example, households receive wages from companies and pay them to buy goods and services. They receive transfers from the State (social assistance, pensions, health reimbursements) and pay taxes and social contributions.

Institutional sectors

National accountants subdivide the national economy into several major institutional sectors:

– general government (state, local government and social security funds),

– households and non-profit institutions serving households,

– non-financial corporations,

– financial corporations.

National institutional sectors also trade with the “rest of the world”, i.e. all economic agents (households, public authorities, companies, etc.) in other countries and international organizations.

National accounts enable us to trace these flows and determine the financial balances of each institutional sector, i.e. the financing needs (deficits) that will have to be covered by debt, or the financing capacities (surpluses) that will feed savings.

As the expenditure of one sector generates the income of other sectors, the financial balances are not independent: their sum leads to a zero result.

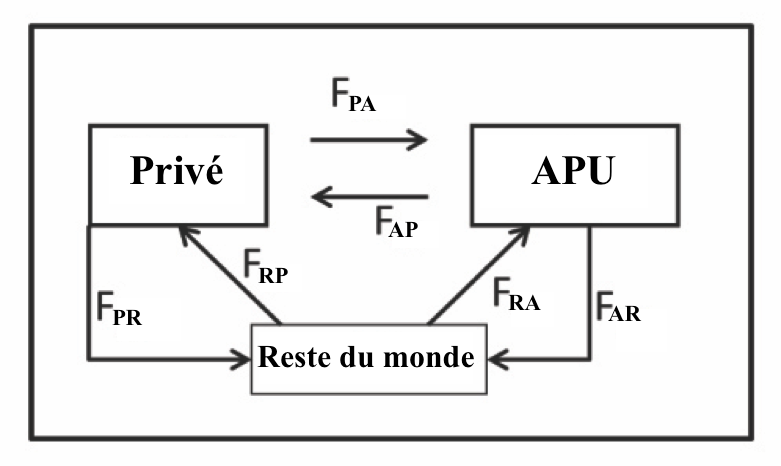

To illustrate this point, let’s take a look at the relationships between three sectors: general government, the private sector (households and businesses), and the rest of the world.

Each sector is symbolized by a letter P = Private, A = Public administration, R = Rest of the world. Flows are symbolized by the letter F.

For example, a flow from the private sector to the public sector is denoted FPA.

By definition :

Private balance = FAP +FRP – FPA – FPR

APU balance = FPA +FRE – FAP –FER

Balance Rest of world = FPR +FAR –FRP –FRA

It’s easy to see that Private + Public + Rest of World = 0.

In other words, for one sector to generate a surplus, at least one of the other sectors must be in deficit.

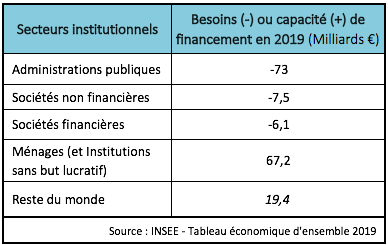

Here’s a numerical example, relating to the French economy as a whole.

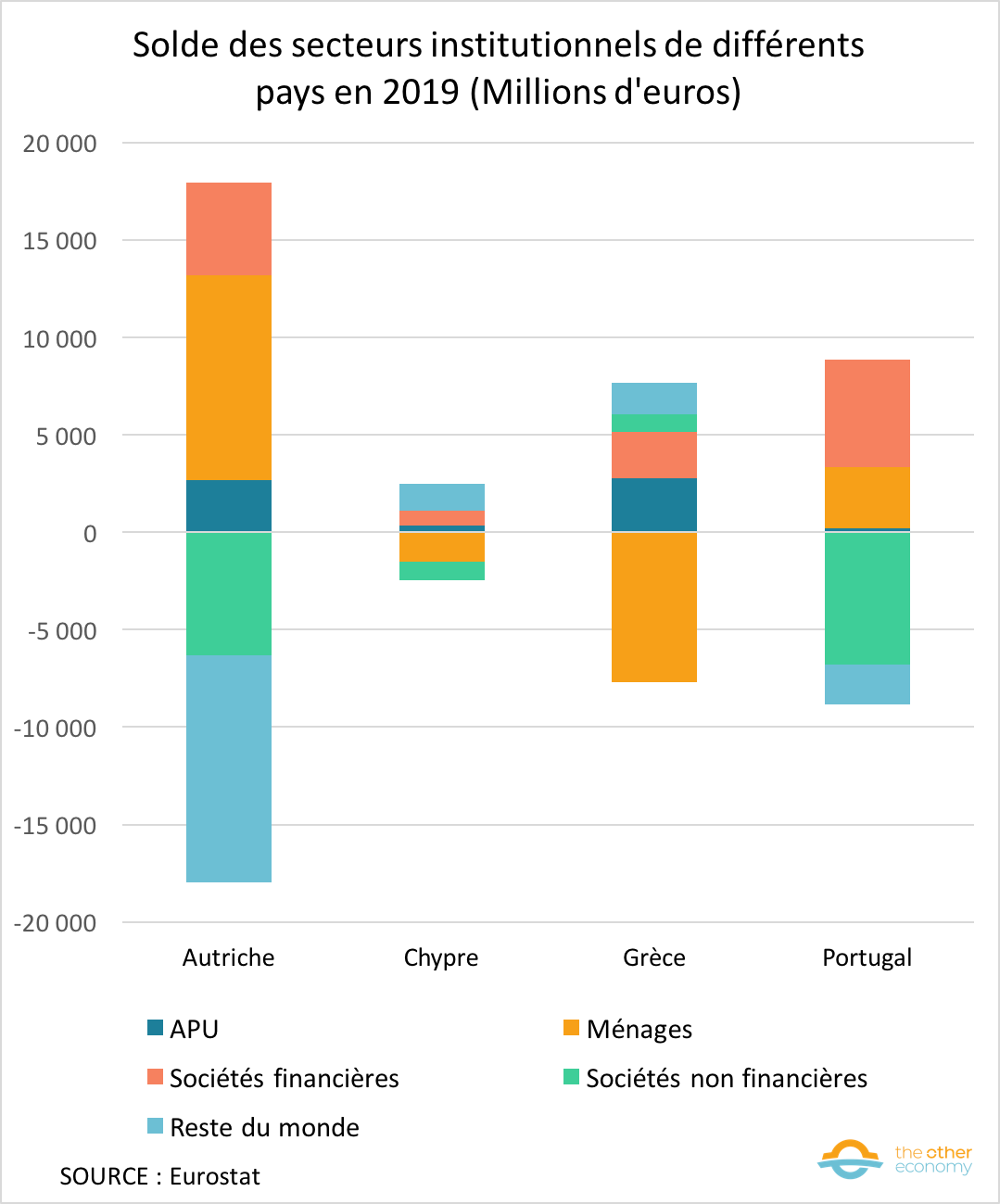

Balance of institutional sectors of the French economy (2019)

Source INSEE – Tableau Economique d’Ensemble (TEE) 2019

We can see that the deficits of general government and companies (financial and non-financial) are offset by the surpluses of households and the rest of the world. We can also see that the French national economy as a whole is in deficit vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

It is therefore irrational to argue that every sector should have surpluses, which would be proof of good management, since this is impossible!

To advocate that public administrations in all countries run surpluses is to advocate that private players run deficits!

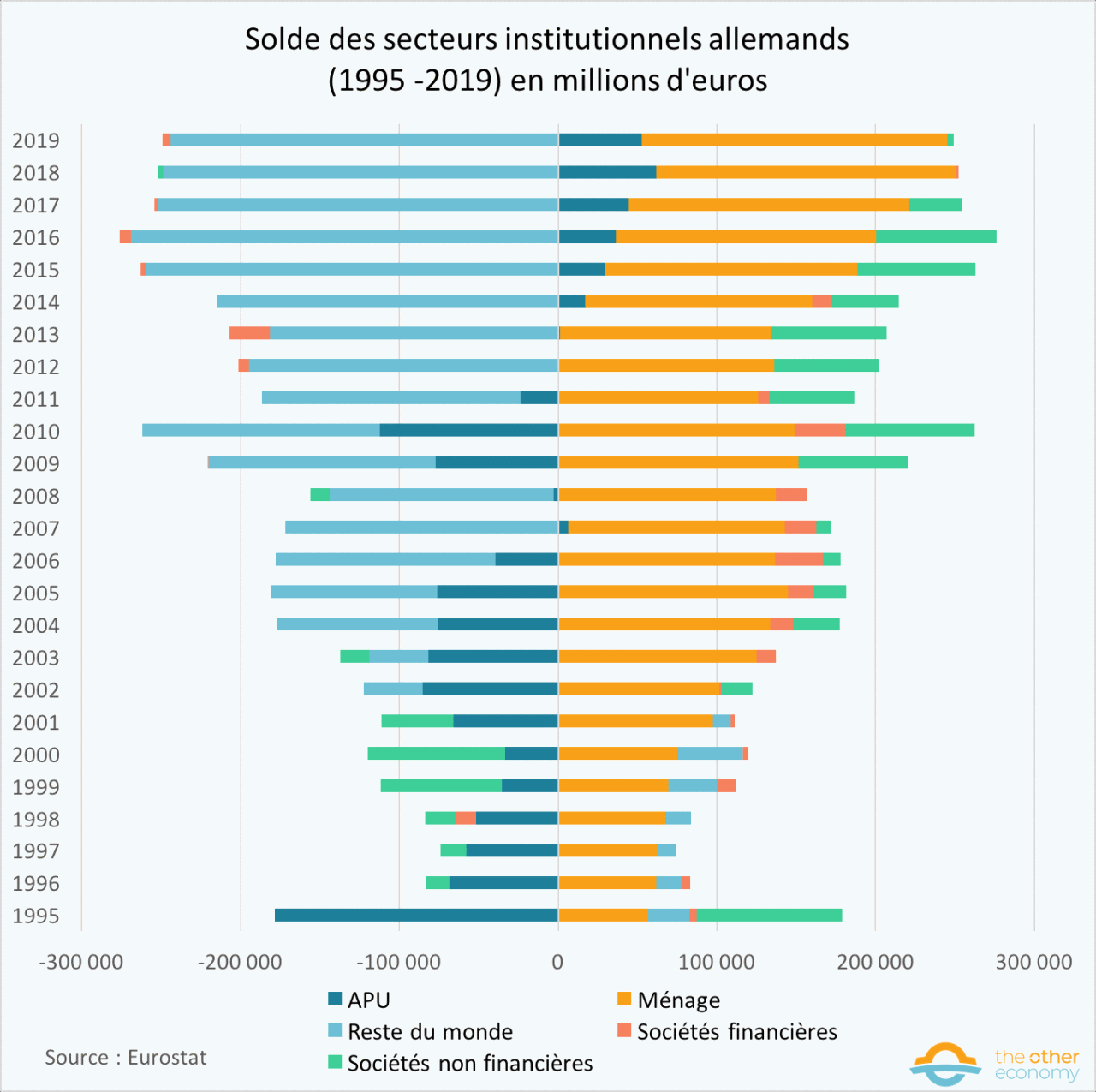

The alternative is for the national economy to be in surplus (and the rest of the world to be in deficit). Indeed, the arithmetical evidence put forward earlier is of course also true between countries: the deficits of some national economies correspond to the surpluses of others.

The case of Germany is particularly striking. The surpluses of its various institutional sectors are only possible because this country has a large surplus vis-à-vis the rest of the world. Of course, it is impossible to generalize this to all countries in the world.

This so-called good management is in fact predatory: the surplus country or agent holds a claim on its debtor and may wish to exercise power over it and benefit (or even abuse) its position as creditor…

Focus on public debt diverts attention from private debt, which is of greater economic concern

While debates focus on public debt, private debt (that of households and non-financial companies) occupies much less media space, even though it is not only far more important, but also more worrying in terms of its macroeconomic impact.

Private debt is much higher than public debt

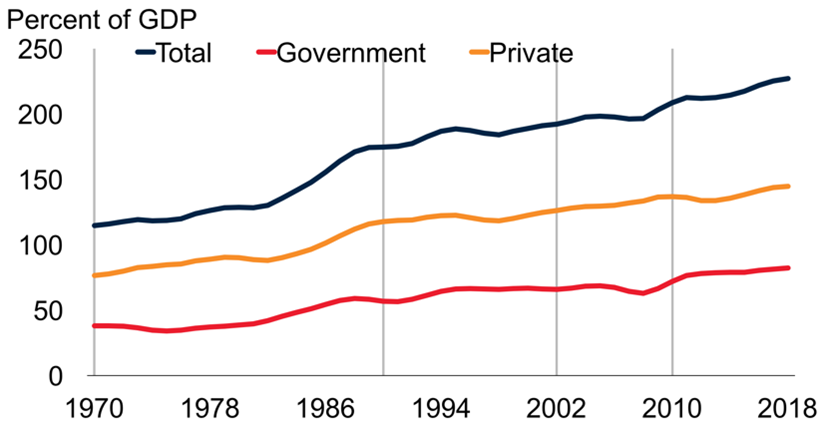

The following graphs show how debt levels (public and private) have risen inexorably since the 1970s. Worldwide, it rose from 114% to 227% of GDP in 2018.

World debt from 1970 to 2018 (as % of GDP)

Source M. A. Kose, P. Nagle, F. Ohnsorge, N. Sugawara, Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences, World Bank, 2020

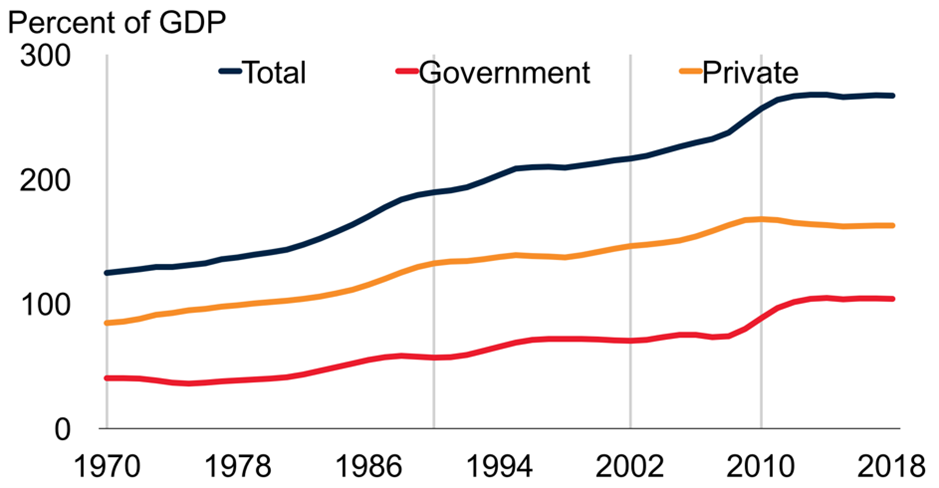

This trend is even stronger in the so-called advanced countries 24 total debt reached 267% of GDP in 2018, compared with 125% in 1970.

Debt of advanced economies from 1970 to 2018 (as % of GDP)

Source M. A. Kose, P. Nagle, F. Ohnsorge, N. Sugawara, Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences, World Bank, 2020

In the years leading up to the 2007-2008 financial crisis, both globally and in advanced economies, the level of private debt was more than double that of public debt. Since then, the gap has narrowed, not least because governments have assumed a large share of the consequences of the crisis, whether by supporting the financial sector or by bearing the social costs of the crisis (rising unemployment, social benefits, falling public revenues).

The spiral of private debt, public debt: the Spanish and Irish examples

In 2007, the Irish and Spanish governments had budget surpluses and very low public debt (24% and 36% of GDP respectively). Their international credit was at its zenith. Three years later, the bursting of the Spanish property bubble and the ensuing violent recession on the one hand, and the state bailout of Irish banks on the other, destroyed their fiscal balances. In 2010, Dublin admitted a public deficit in excess of 32% of GDP, while Madrid admitted a deficit of 9.5% of GDP. Irish and Spanish public debt exploded (60% of GDP for Ireland and 80% for Spain in 2010).

Source Eurostat – tables on public debt as a % of GDP and public balance as a % of GDP

Private debt was at the heart of the two greatest financial crises in history

The importance of private debt is of great concern, as the fundamental cause of both the 1929 crisis and the 2007-2008 crisis was the bursting of a speculative bubble financed by debt.

Indeed, rising debt and speculative bubbles go hand in hand. One of the main reasons for this is that loans are granted with “collateral” in the form of speculative assets (real estate or financial securities). Both supply and demand for credit increase in line with expectations of rising asset prices. In this mechanism, there is no restoring force. Lenders feel (wrongly over time) protected by the rising financial value of the collateral (speculative asset). Borrowers increase their demand for loans as speculative bubbles develop, in order to realize capital gains (they take on debt to buy assets they believe they can then sell for more).

Once the speculative bubbles have burst, the excessive indebtedness of economic agents prevents any way out of the crisis. Over-indebted agents focus on repaying their debts and under-invest. This pro-cyclical behavior exacerbates the depression.

These various mechanisms were well demonstrated by economists Irving Fisher and Hyman Minsky, and later by Steve Keen 25 . They are at the root of Japan’s long stagnation after the 1991 financial crisis.

Public and private debt continue to grow

By focusing on public debt alone, the debate in Europe tends to present the countries of Northern Europe as “frugal”, with sound budgetary management, and the countries of Southern Europe as “cicadas”, spendthrifts and irresponsible.

When you look at the overall debt figures, you can see just how biased this interpretation is.

Public and private debt as % of GDP in various countries in 2019

MISSING DATAVIZ: f688706c-d762-42fa-a1d0-7061366ba105Source: Global Debt Database (IMF).

As can be seen, all countries have very high levels of debt. On the other hand, countries with low levels of public debt, such as the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Luxembourg and Denmark, have very high levels of private debt. Germany and Austria, on the other hand, manage to limit their economies’ indebtedness to around 200% of GDP. One reason for this may lie in the fact that Germany and Austria have a current account balance of 26 for almost two decades. Note that this is not a sufficient condition, as it is also the case in Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands. It is, of course, impossible for all countries to have a current account surplus at the same time.

Thinking about private and public debt at the same time helps us understand the extent to which debt is at the heart of the economic system. It’s no longer a question of morality, of “cicadas” or “ants”. The widespread indebtedness of economies is not the result of poor budgetary management on the part of agents, but simply a state of affairs. Debt is the result of the way in which trade is organized, investment is financed, value added is distributed and money is created (see module on money).

This shift in focus away from public debt alone raises new questions. For example, is it possible to design a monetary and financial system that does not rely so heavily on debt (see Essential 5: “The explosion in public debt is linked to money creation mechanisms”)?

European budgetary rules are not economically rational

At the heart of European economic governance are two key indicators of budgetary discipline for EU member states: the public deficit must be below 3% of GDP, and public debt must be below 60% of GDP.

The decision to enshrine these criteria at the very heart of the treaties 27 at the very top of the European Union’s hierarchy of norms. It amounts, in effect, to considerably restricting States’ room for maneuver, by placing the control of debt and public spending at the heart of economic policies (and, more generally, of public policies). How do we react to a financial crisis or recession? How can we invest in the transformations required by the ecological transition?

These rules, set in the marble of the Treaties, are not flexible enough to meet the challenges faced by governments at any time and in any place. That’s why they were suspended in 2020, by activating the “general derogation clause”, to enable states to deal with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Today, these rules are the subject of much criticism, and many players are calling for a reform of European economic governance (see our Proposals section for more details). Below we outline some of the main objections to these rules, without being exhaustive.

European economic governance

Gradually implemented since the Maastricht Treaty (1992), since 2011 European economic governance has taken the form of an annual coordination cycle known as the “European Semester”.

It consists of a set of rules and procedures designed to enforce budgetary discipline among member states, facilitate coordination of their economic policies and prevent macroeconomic imbalances. While such coordination is necessary in an Economic and Monetary Union (for the euro zone) of highly interdependent states, European governance is hampered both by its extreme complexity and by the predominant place accorded to budgetary surveillance.

The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), the cornerstone of this governance, deals almost exclusively with how to respect the binding criteria of public deficit and debt. In particular, it aims to ensure compliance with two budgetary rules: the deficit must be less than 3% of GDP, and public debt must not exceed 60% of GDP. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, a procedure concerning macroeconomic imbalances was introduced, but it clearly does not carry the same political weight.

This focus on public spending, deficit and debt levels keeps quality of life and environmental sustainability out of economic and financial policy.

In early 2020, the Commission launched a process to reform economic governance, and at its heart, the European budgetary framework.

Find out more with our fact sheet on European economic governance.

There was no economic rationale behind the rules governing debt and deficit

Senior French civil servant Guy Abeille tells the story of the development of the 3% GDP deficit criterion. 28 . It was drawn up one evening in June 1981 on a table corner, in response to President François Mitterrand’s cyclical and political objectives.

It’s clear that focusing on a given year’s deficit makes little sense, and that relating it to that year’s GDP makes it even less meaningful. The deficit-to-GDP ratio can at best serve as an indication, a gauge: it gives an order of magnitude […]. But under no circumstances can it serve as a compass; it measures nothing: it is not a criterion.

This indicator was then extended to the rest of the European Union following the Maastricht Treaty negotiations (1992).

As for the 60% public debt limit, it is no more justified: it represents no more than an average of the public debt levels of the 12 countries that made up the European Union at the time. A calculation of consistency between the two indicators has been made a posteriori: if the GDP growth rate is 5% (3% in volume, 2% in inflation), the deficit (after interest payments, i.e. whatever the level of interest rates) is 3% of GDP, and if public debt is 60% of GDP, then this 60% level remains constant. Note that the growth rate assumptions were “heroic”, and that the 60% level was not respected by several countries when they joined. This calculation cannot be taken at face value, given the complexity and variety of European economies. Moreover, the ratio itself is in no way sufficient to determine the level of debt sustainability (Myth 2).

In fact, the debt and deficit rules were devised during the Maastricht Treaty negotiations to alleviate the concerns of certain States regarding the consequences of the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (the euro zone). This was characterized by the introduction of a common monetary policy, conducted by an independent central bank focused on price stability and prohibited from acting as lender of last resort to the States. At the same time, there is no common fiscal policy or fiscal capacity. As states finance their deficits on the financial markets, some governments have feared the risk of contagion: poor management of public debt by certain states could lead not only to higher interest rates on their own debt, but also on that of other eurozone countries. The rules and principle of budgetary surveillance enshrined in the Treaties are therefore part of a desire to control the tendency of governments to run deficits (presumed to be structural – see Box on Public Choice Theory in Essentiel 1).

Recurring criticisms: procyclicality, asymmetry, public disinvestment

Pro-cyclical rules

Once the thresholds of 3% or 60% of GDP have been exceeded, governments are obliged to reduce their deficits (usually by cutting public spending), or even generate surpluses, regardless of any other consideration, including the business cycle (i.e., whether there is sustained growth or economic slowdown, or even recession).

This obligation has led to a pro-cyclical bias in European budgetary rules, particularly in times of economic difficulty, since strict compliance with these rules means that the budgetary tool cannot be used in the event of a recession. 29 . It was the desire to comply with these rules that led to the abrupt halt to post-financial crisis stimulus policies in the early 2010s.

The implementation of our budgetary framework turned the global financial shock of 2008 into a lasting economic crisis and plunged Europe into recession for longer than necessary. It has led to years of public and private under-investment, hampering the achievement of our environmental goals while causing a resurgence of inequalities within and between EU countries.

Asymmetrical rules with a deflationary bias

In its 2019 report, the European Budget Committee highlights the imbalance between the rights and obligations of eurozone countries. While countries with high levels of debt are obliged to pursue restrictive policies, those with low levels of debt, large budgetary margins and trade surpluses are not obliged to pursue expansive policies. The result is a deflationary bias.

This point has been made by many observers, including the Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Paolo Gentiloni, who at a conference at the European Central Bank stressed how damaging this imbalance is in an environment of low growth and low inflation, when the effectiveness of monetary policy is running out.

In the view of the European Budget Committee, this asymmetry, combined with the lack of differentiation of rules between countries, renders ineffective the concept of an aggregate fiscal stance for the eurozone, which is nonetheless relevant in an Economic and Monetary Union.

European accounting rules are detrimental to public investment

Excessive focus on numerical limits leads to indiscriminate cuts in public spending, with no regard for quality. This has manifested itself in particular in a decline in public investment across Europe, as it is often politically easier to refrain from investing than to reduce regular expenditure, such as civil servants’ salaries and social benefits (which has not prevented cuts in these areas).

This is all the more true given that the calculation of the public deficit, as established by the European System of National and Regional Accounts (ESA 2010) 30 is similar to the cash requirement and, unlike company accounts, does not take into account the depreciation of investments.

Philippe Maystadt, former President of the European Investment Bank, comments on the failure to distinguish between operating and capital expenditure:

The consequences for public investment of the strict application of European accounting standards SEC 2010 are enormous. Capital expenditure must now be charged directly and in full to the deficit of the year in which it is incurred. It is no longer possible to consider that capital expenditure can be amortized over several years. If the cost of investments amortized over an average of 6 years has to be charged to a single year, it is to be feared that, with a constant deficit, public investment will fall by a factor of 6. A fine example of European schizophrenia.

It should be remembered that the aim of business accounting is to show an economic result (profit or deficit) that reflects changes in the company’s equity capital, and not just its annual financing requirement (which is of course also calculated). For a given year, it takes into account not the amount of the year’s investments, but their amortization over an economic or conventional period. A company director will take a close look at his assets 32 and their present and future value. He will invest not only according to his cash position, but also according to the prospects offered by this investment, i.e. the evolution of his net assets (in other words, his shareholders’ equity) and his ability to “balance” his financing needs (either through self-financing, debt or a capital increase).

In contrast, the public deficit, as defined by the European System of Accounts, is a balance characterizing only the need for financing (close, therefore, to a cash balance). This orientation is clearly linked to the management of public debt, rather than to a patrimonial reasoning. The current way of accounting for public expenditure therefore presents a worrying bias, leading public decision-makers to under-invest, as it is more difficult in the short term to reduce operating expenditure (notably personnel costs) than capital expenditure. Calculated in this way (and given its importance in European treaties), the public deficit focuses the public decision-maker’s attention on the situation of his short-term financial commitments, and not at all on “public assets” and its assets (financial and non-financial – see Essential 6: “Opposite public debt there is an asset”).

General government GFCF (as a percentage of GDP) 2000-2019

The decline in public investment is already visible when we look at gross investment, which has fallen as a % of GDP.

The indicator traditionally used is gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), a national accounting aggregate that can be defined as a measure of investment by the various public and private players in society (more details on the Insee website).

MISSING DATAVIZ: e8c60aad-8423-4c34-babc-c8400e446718Source European Commission Ameco database (series 3.2 – General government).

It is even more so for net public investment. 33 which has been close to 0, or even negative, in Europe for several years. This means that eurozone countries are barely investing enough to maintain and renew public infrastructure (transport, public buildings such as hospitals, barracks, schools, water and waste treatment plants, etc.). It’s this kind of trajectory that leads to disasters such as the derailment of the Corail Intercités train at Brétigny-sur-Orge in July 2013 or the collapse of the Genoa bridge in summer 2018.

Net public investment 2000-2019 for several eurozone countries (€ billions)

MISSING DATAVIZ: 8907a053-4255-4fc1-9161-03e095841b93Source Ameco database (Series 3.- General Government)

European economic governance is blind to ecological and social issues

More generally, the Maastricht rules have induced a fundamental bias in European economic governance which, despite significant changes, remains dominated by the priority of budgetary discipline.

For example, employment and environmental indicators have been included (in 2015 and 2020 respectively) in the European Semester, an annual cycle of economic policy coordination, but they are mainly indicative. Most of the binding procedures analyzed during the Semester focus on short-term budgetary management objectives. Long-term environmental and social objectives are dealt with in other coordination processes, independently of economic coordination.

Yet it is clear that economic policies have a major influence on the state of the EU’s environment and the achievement of its climate and biodiversity objectives. Conversely, destabilization of the climate and the environment already has economic and financial repercussions, as well as on public finances (via, for example, public support measures taken following extreme climatic events such as storms, floods, heat waves etc.).

This feedback loop between public policy and the environment should be placed at the heart of European economic governance. However, not only do EU budgetary rules fail to take these issues into account, but worse still, they contribute negatively to them by limiting public spending and investment, without taking into account their impact on the Union’s environmental or social objectives (as we saw in section 9.2 above).

Find out more

Criticism and calls for reform of the European budgetary framework have come from public institutions, business and civil society alike.

- Assessment of EU fiscal rules, report by the European Budget Committee commissioned by the Commission (2019)

- Annual Report 2020 of the European Budget Committee

- Redesigning EU fiscal rules: From rules to standards Olivier Blanchard et ali, Working Paper PIIE (2021)

- Europe should not return to pre-pandemic fiscal rules, Joseph Stiglitz, Financial Times (2021)

- Open letter to European leaders from 68 European NGOs and trade unions, supported by a hundred academics (2021)

- Call: A resilience and solidarity pact to replace the Stability and Growth Pact (2021)

- Interview with Klaus Regling (one of the fathers of the SGP) Director of the European Stability Mechanism (2021)

Proposals to reform the European budgetary framework

- The reform of the EU fiscal framework, position of Climate Action Netwaork (CAN europe) 2021

- Analysis of the feasibility and impact of proposals to reform European budgetary rules, ZOE Institute (2021)

- One Framework to rule them all, Ludovic Suttor-Sorel, Finance Watch (2021)

- What European budgetary framework for the ecological transition, Ollivier Bodin, contribution to the FNH Think Tank (2021)

The public deficit is a tool to fight economic crisis

The response of governments to the financial crisis of 2007-2008, and even more so to the COVID-19 pandemic, has shown the extent to which the mobilization of public budgets is fundamental to dealing with an economic crisis. Several mechanisms are at work.

The need for a counter-cyclical policy

A counter-cyclical policy is defined as one that runs counter to the economic cycle. In the case of a recession, this means that far from tightening its belt like the majority of economic agents, the public authorities increase their spending and/or reduce their revenue (taxes).

The example of the response to the economic crisis following the COVID-19 pandemic

Clearly, the mobilization of public budgets was fundamental in tackling the economic crisis following the measures taken in 2020 in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. If the States, supported by their central banks, had not spent “lavishly” to support household and business incomes immobilized by successive confinements, the economic crisis would have been far more severe than the one we experienced. Faced with an economy at a standstill, only the public authorities were in a position to support the incomes of private players and thus maintain the productive capital of their respective countries.

While the situation is unprecedented, it nevertheless highlights just how essential government intervention is in times of economic crisis. It is also essential once the worst of the crisis has passed, through a policy of recovery, to restore a sufficient level of activity, since recession is a self-perpetuating phenomenon. Schematically, this is how it works.

The vicious circle of recession

Faced with a difficult economic situation, it’s in every economic agent’s interest to “tighten the belt”. The reflex of a business owner noticing (or anticipating) a drop in orders (which, for a company, is the concrete expression of a recession), will be to reduce expenses. 34 and, if necessary, sell off some of their assets to improve cash flow and reduce debt.

As a company’s expenses are income for others, their reduction contributes to a reduction in consumption and investment by other economic players. Faced with rising unemployment, wage stagnation and loss of income, households will also be “tightening their belts” by cutting back on consumption and building up precautionary savings, where they can, to tide them over difficult times. Similarly, bankers will be more cautious, reducing their lending or increasing the cost of loans.

All these behaviors point in the same direction: downward pressure on aggregate demand. If it is rational for a company, a household or a bank to adopt such procyclical behavior, when all economic agents do so, it is the national economy that collapses, eventually dragging other countries into the recession. The aggregation of rational microeconomic behavior in the face of a recession can only lead to its prolongation.

This vicious circle can only be broken by government intervention, through automatic stabilizers and stimulus policies. It should be noted that the aim here is not to glorify a consumer-driven stimulus (whose excess is ecologically unsustainable), but to show the role of public spending in avoiding a sudden and necessarily socially unjust decline.

The role of automatic stabilizers in mitigating recession

Public finances play a role in mitigating the economic cycle, without the authorities even needing to decide to implement specific measures, by means of automatic stabilizers. The principle is simple: in times of recession, the taxes levied are automatically reduced (notably VAT on consumption), while existing social benefits, such as unemployment benefits and minimum social benefits, limit the loss of income due to job losses. The automatic mobilization of public finances thus contributes to mitigating the consequences of cyclical events on activity and supporting aggregate demand. The impact of these automatic stabilizers obviously varies according to the tax and social protection systems in place in the countries concerned.

Stimulus policies and the multiplier effect of public spending

While automatic stabilizers can attenuate shocks, they are often insufficient to pull the economy out of recession. In such cases, a stimulus policy is needed: public demand must replace private demand to prevent the economy from sinking into recession. The greater the fiscal multiplier, the stronger the effect of this policy.

What is the fiscal multiplier (also known as the Keynesian multiplier or the investment multiplier)?

The fiscal multiplier is the ratio between the variation in national income (GDP) and the variation in public spending. If it is greater than 1, this means that every additional euro of public spending generates more than 1 euro of additional overall economic activity.