This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

While it’s impossible to do without finance, it has become too important and too powerful. Its complexity, whether apparent or real, makes it difficult for the layman to access. This is an unhealthy situation in a democracy. Because the sometimes very high incomes of traders and other players are well known. Because the power of finance is clearly as great as it is poorly controlled, as shown by the work on “regulator capture”. 1. Let’s try to untangle this financial skein and see how we can put finance back at the service of citizens and the ecological transition.

The essentials

Finance carries out missions of general interest

Finance brings together all the institutions responsible for creating money and/or channelling savings (mainly from households and businesses) towards economic agents in need of financing.

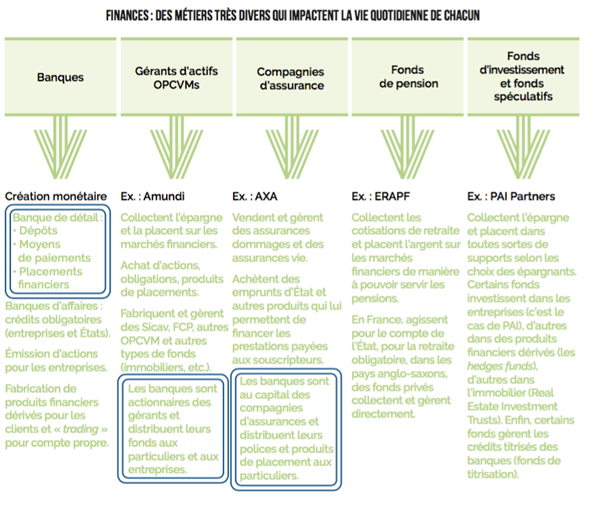

These financial entities can be grouped into five main categories:

- BANKS ;

- insurance companies, some of which are bank-owned;

- pension and retirement funds;

- collective management organizations ;

- and investment funds, some of which are speculative.

As the following diagram shows, each of these financial entities has different activities and functions.

Source “La finance aux citoyens”, Secours Catholique – Caritas France report, 2018.

By determining which players can access financing to bring their projects to fruition, and under what conditions, financial players play an essential role in the smooth running of the economy. Their activity is at the service of all other economic sectors and, in this respect, concerns the general interest. We would like to emphasize the following points:

Banks create money and analyze credit risks

Money is created by banks

Banks are special financial institutions: they play a specific and important role in the economy.

On the one hand, by managing deposits and means of payment, they are at the heart of the payment system, the major infrastructure of any market economy. The sudden closure of banks would paralyze the economy, as the vast majority of exchanges would no longer be able to take place in the absence of the tools needed to carry out the related financial transactions.

On the other hand, banks, mainly through their lending activity, create money and thus additional purchasing power, enabling projects to be carried out that would otherwise not have been possible(see the module on money). By deciding whether or not to grant credit, banks decide how and to whom the new purchasing power is directed, and which projects are or are not financed and can be carried out. In this, they have an important responsibility. If too much money is created, or allocated to the wrong projects, it can have harmful effects on society and the economy(see the module on money and Essentiel 4 below).

Risk analysis

Banks therefore also play an important role in analyzing credit quality. It’s a question of making a loan that’s well advised (i.e. that has a reasonable chance of being repaid by the borrower) without being overly cautious (which would also ruin the lender’s business, who needs to know how to take “reasoned” risks). Although the proverb says that you only lend to the rich, the reality is more nuanced, and we have to acknowledge that some banks have real expertise in this field: they are capable of analyzing a credit risk and proposing interest rate and collateral conditions adapted to the lender on the basis of this analysis.

The importance of serious credit analysis

The best proof of the social value of this activity was given a contrario by the ” subprime ” crisis. Loans granted without any serious analysis (the famous “ninja” loans: ” no income, no job, no asset “) had a negative impact on the economy. 2) were granted because they could be securitized, i.e. partially or totally removed from the balance sheet of the lenders and resold on the financial markets. This practice distanced the links between borrowers and final credit holders, diluting and spreading the credit risks associated with the entire financial system. The major crisis that ensued demonstrated the importance of serious credit analysis.

Find out more in our securitization fact sheet .

Financial players channel existing savings into new economic projects

In addition to bank money creation, financial players collect existing savings, i.e. the portion of income (mainly household income) that is not spent on current consumption, and use it to meet the financing needs of companies, households or public authorities.

In this respect, they play an important economic role, since they enable more (financial) resources to be used in the economy than would be the case if each saver were to invest directly: it is more difficult for an individual to identify and select projects or companies; financial players offer individuals the possibility of recovering, under certain conditions, the capital invested, thus reassuring savers.

Difference between primary and secondary markets :

Le marché primaire désigne le « marché du neuf », celui sur lequel un émetteur (un État, une entreprise) introduit pour la première fois des titres financiers (actions, titres de dette).

These securities can then be traded on the secondary market, a “second-hand market”. The value of the secondary market lies in the fact that it ensures the liquidity of financial securities, i.e. the possibility of converting them more or less rapidly into money. It thus facilitates the mobilization of capital to finance investments in the productive economy. Without this possibility, far fewer savers would consider allocating their financial assets to finance long-term projects that do not directly concern them.

The existence of secondary markets is not without perverse effects

The primary market is the only way to finance the productive economy. Savings channeled into the secondary market certainly ensure the liquidity of securities (and thus facilitate the issuance of these securities on the primary market), but it also has the effect of driving up their price (since they are in greater demand) and, if savings are in excess, creating destabilizing financial bubbles.

Moreover, the liquidity of financial securities at a given moment does not guarantee that this will always be the case. It gives the dangerous illusion of unconditional reversibility of financial decisions. In the event of a financial crisis, markets become illiquid: nobody wants to buy securities any more, everyone wants to sell, and prices plummet (see our fact sheet on liquidity ).

Finance helps manage risk

The development of financial techniques goes back a long way. European merchants would doubtless have been less adventurous in the Middle Ages had it not been for the inventiveness of financiers offering them insurance or “paper” instruments (such as promissory bills) that would have saved them the trouble of carrying gold coins. 3.

The mission of finance and insurance is to manage the risks associated with economic activity. These are difficult professions, requiring experience and methods that can legitimately be sophisticated (because the activities of the real economy can be complex). It would therefore be counter-productive to deny all interest in financial innovation and to prohibit all new financial products on principle.

More precisely, finance manages risk from a specific perspective: the trade-off between return and risk. The idea is simple: every economic player takes a risk with every transaction (see box). When they don’t bear the risk directly (particularly in the credit business), financial players offer services that either delegate the management of this risk-taking, or hedge it partially or totally (via derivatives ). In exchange, they expect a return (which may take the form of an interest rate, dividends, etc.). The higher the risk, the higher the expected return.

Examples of risks taken by various economic players

- A lending banker takes the risk of not being repaid, or being repaid late.

- A company exporting a good takes on at least two risks vis-à-vis its customer: the risk of not being paid, and the risk of being paid in a currency that has lost value. If the currency is not automatically convertible, it also takes on the risk of inconvertibility (see the module on currency).

- A household that invests its savings takes the risk that they will lose value (through inflation or because the chosen investments have lost their value).

If there aren’t many truths in the financial world, there’s one we can remember: it’s an illusion to believe that you can earn money over the long term by investing it risk-free. The financiers in charge of investing household money, insurers, asset managers and pension funds all know this, and use a formula which, in this case, has a precise and very accurate meaning: ” there is no free lunch “. 4. This is the idea that there is no such thing as a financial strategy that, for zero initial cost, will enable you to acquire definite wealth. Even more technically, there are no arbitrage opportunities on the financial markets. Financial advisors who offer “martingales”, who promise “magic” returns, are swindlers or liars (at least by omission). They deliberately or inadvertently forget to mention the risk they are passing on to those who follow their advice. This idea is sometimes confused with that of market efficiency, which is, on the contrary, a dogma without any foundation or precise definition (see Misconception 1).

The banking and financial sphere has grown by leaps and bounds in recent decades.

In the vocabulary of finance, financialization refers to the increased reliance of all economic agents on external financing, and in particular debt, compared with previous periods. Over the past 50 years, the world economy has clearly become increasingly financialized, with finance playing a growing role in the global economy. This financialization is the result of economic and political evolutions that have affected most advanced economies since the 1970s (see Essentiel 3).

Numerous indicators show the growth of the financial sphere relative to the productive economy:

- the growth in the relative weight of the banking and financial sector in GDP, the growth in the income of individuals working in the financial sector and their growing share of the highest incomes;

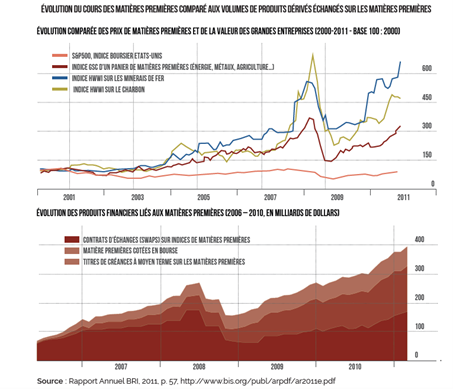

- the relative weight of goods that are the subject of a financial market (oil, gas, coal, metals, foodstuffs such as wheat, soya, etc.);

- growth in the volume of “derivatives”;

- the growing dependence of governments on financial markets for their financing.

- the weight of finance in corporate shareholding (compared with that of individuals and non-financial companies) – see Essentiel 5.

Disconnecting the financial sphere from the productive economy

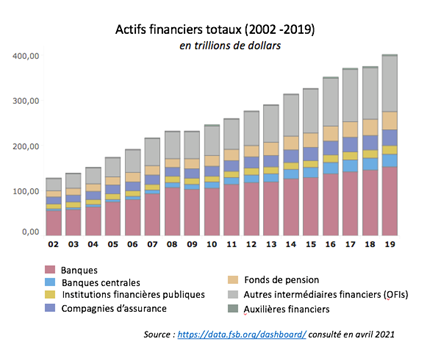

According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB) 5global financial assets have risen from around $128,000 billion in 2002, or 370% of GDP, to over 400,000 billion euros in 2019, or 460% of GDP. As can be seen from the following graph, the crisis of 2007-2008 only slightly slowed the continued growth of the financial sphere.

Source This graph is taken from the scoreboard maintained by the Financial Stability Board.

As economists Gunther Capelle-Blancard and Jézabel Couppey Soubeyran point out in the article Une régulation à la traîne de la finance globale (2018), the lack of strict proportionality between flows in the financial sphere and those in the productive sphere is not surprising in itself. For example, it’s understandable that in order to finance international trade activities and hedge the associated risks (currency and interest-rate risk in particular), several flows are required on the foreign exchange and derivatives markets 6. “However, when 70 times the value of international trade is exchanged on the foreign exchange market in a single year, there is every reason to believe that the financial sector is no longer serving the real economy, and is now primarily serving itself.

The excesses of finance

In the same article, the authors highlight “some measures of excess” in finance:

« Nombreuses sont les mesures à partir desquelles on peut rendre compte de l’explosion de la finance. Dans les pays de l’OCDE, le crédit au secteur privé est passé en moyenne d’environ 50 % du PIB dans les années 1970 à plus de 100 % du PIB au moment de la crise financière, sans beaucoup fléchir depuis 7. Le bilan des banques a crû à un rythme exponentiel au tournant des années 1990-2000, tout particulièrement en Europe, où il représente désormais l’équivalent de 3,5 fois le PIB, contre 1,8 fois au Japon et 1,2 fois aux États-Unis 8. La crise financière de 2007-2008 a ralenti cette tendance, mais elle ne l’a pas inversée. Au niveau mondial, les actifs gérés par les banques ont pratiquement triplé au cours des années 2000, passant d’un peu plus de 50 000 milliards de dollars fin 2003 à 133 000 milliards de dollars fin 2015 [ndr 155 000 milliards de $ en 2019] 9.

Transaction volumes on the stock, foreign exchange and derivatives markets also illustrate this disproportionate growth. These financial quantities are now out of all proportion to those of the real world. Remember that in 2008, merchandise trade between the G7 countries was worth $3,000 billion (before declining with the crisis), and global GDP was worth $75,500 billion in 2016. And yet, despite the crisis and the slowdown it may have brought about, financial transactions amount to hundreds of thousands of billions of dollars. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) estimated the notional amount of derivatives outstanding at $483,000 billion at the end of December 2016 [ndr $558,500 billion in 2019].

As far as the foreign exchange market is concerned, the BIS triennial survey published in 2016 suggested a slight contraction, but still estimated the daily volume of foreign exchange transactions at over 5,000 billion (equivalent to more than 2.5 times the GDP of a country like France in a single day) [ndr $6600 billion at the end of 2019].

And last but not least, equity market transactions today amount to more than $100,000 billion every year, equivalent to almost 150% of global GDP, compared with just 5% in 1975. 10. This increase is essentially driven by the boom inhigh-frequency trading (HFT), which now accounts for between half and two-thirds of trading volumes, with transactions carried out at microsecond intervals.”

Financialization took off in the 1970s as a result of neo-liberal political decisions.

Les décennies qui suivent la Seconde guerre mondiale sont marquées par un strict encadrement du secteur financier, parfois qualifié de « répression financière » 11 : système de change fixe et contrôlé reposant sur la convertibilité du dollar en or 12 mis en place à la suite des accords de Bretton Woods ; contrôle des mouvements de capitaux transnationaux ; encadrement des activités de crédit ; segmentation de l’industrie bancaire et financière. Les États se financent en mobilisant l’épargne intérieure, en obtenant des prêts préférentiels auprès de publics nationaux captifs (tels que les fonds de pension ou les banques nationales) ou auprès de leur banque centrale.

De façon générale, les banques centrales sont dans une position de relative subordination vis-à-vis de gouvernements : la politique monétaire est utilisée en complémentarité avec la politique budgétaire pour mener des politiques économiques visant à soutenir l’activité ou à la freiner en période de surchauffe. C’est également à cette époque que se développe l’État providence, système d’assurance sociale mutualisée au niveau national, dans de nombreux pays.

This period of strong state intervention in the economy gradually came to an end in the 1970s. Against a backdrop of greater instability, marked in particular by the end of the Bretton Woods exchange rate system, oil shocks and the emergence of stagflation (concomitant inflation and mass unemployment), neoliberal theses, which had hitherto gone unheeded, gained ground in political circles on both the right and left in advanced countries. The aim is to promote the market economy and the “open society” on a global scale, and to limit public intervention in the economy to ensuring social stability and the smooth functioning of markets.

In financial terms, this is reflected in a vast movement towards liberalization and globalization, sometimes referred to as the 3D movement. 13 movement” (deregulation, decompartmentalization, disintermediation). Without claiming to be exhaustive, let’s highlight just a few of the major developments in this movement.

The end of the Bretton Woods Agreement and the introduction of a floating exchange rate system

In August 1971, faced with the melting of the country’s gold reserves, US President Nixon decided to suspend the convertibility of the dollar. The new system of floating exchange rates was ratified by the Jamaica Agreements in 1976. Henceforth, the price of currencies on the foreign exchange market would evolve according to supply and demand. This opened the door to currency speculation. Currency crises multiply around the world 14 with major consequences for the economies concerned, given the importance of the exchange rate on the price of exports and imports. (See Essentials 11 and 12 in the currency module). Moreover, the introduction of floating exchange rates, by creating a new risk (currency risk) in international trade, will provide the impetus for the growth of derivatives.

Free movement of capital

La fin du système de Bretton Woods s’accompagne de la levée progressive du contrôle des mouvements transnationaux de capitaux. A partir des années 1980, les pays avancés, États-Unis en tête, ouvrent progressivement le marché des titres de leur dette publique aux investisseurs étrangers. Les acteurs financiers reçoivent ensuite la possibilité non seulement d’investir partout où ils le souhaitent sur la planète, mais également de s’installer dans d’autres pays pour concurrencer les acteurs financiers locaux. Ces politiques seront également promues voire imposées aux pays en développement à la suite de l’adoption de la doctrine dite du consensus de Washington par le FMI et la Banque Mondiale 15. L’ouverture des frontières aux mouvements de capitaux, a plusieurs conséquences négatives pour l’économie mondiale : elle concourt à l’émergence de méga-banques, favorise le développement des mouvements spéculatifs internationaux déstabilisant les économies nationales, et facilite les phénomènes d’évasion fiscale et de blanchiment d’argent dans des paradis fiscaux.

The deregulation of lending activities and the development of prudential regulation of banks

From the 1970s onwards, most advanced economies deregulated the credit sector, gradually removing some of the limits on banks. All rules aimed at directly limiting (via quotas, for example) the quantity of credit granted by banks, as well as the orientation of credit according to economic sectors, came to an end. This period also saw the end of bank specialization by type of activity (retail banking, investment banking, banks specializing in local credit, etc.), or by geographical area (in the United States, for example, banks were not allowed to expand beyond a single state). Many governments allow banks to engage in non-banking activities, such as insurance or asset management. Some countries are also lifting constraints on borrowers.

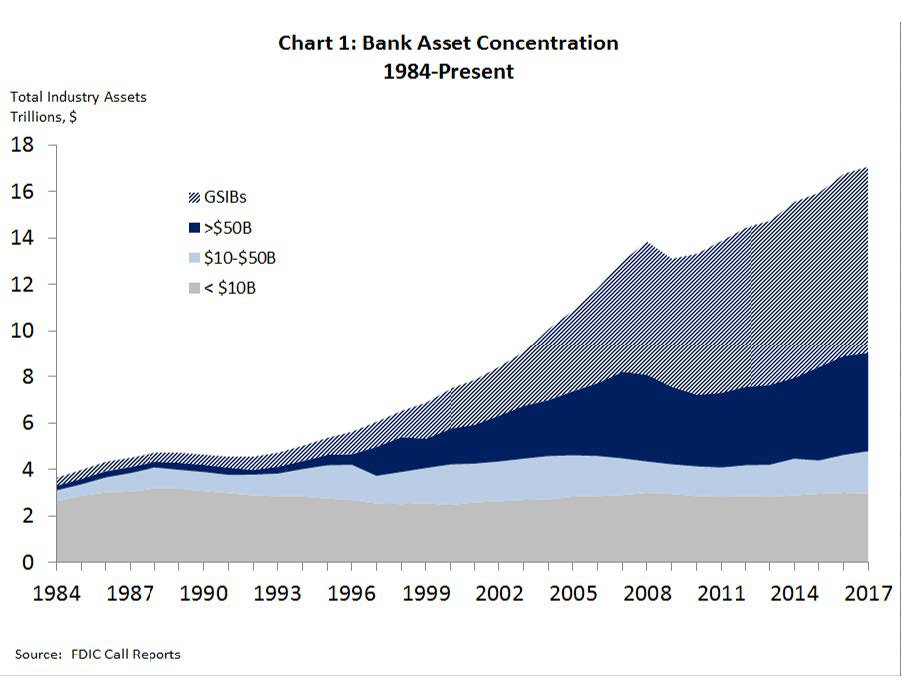

These different trends are reflected in the concentration of the sector, leading to the emergence of international mega-banks, some of which are “universal” in the sense that they are active in all areas of finance.

At the same time, following the resurgence of banking crises virtually unheard of in the previous period, prudential regulation of banks developed with the establishment of the Basel Committee. Banks were required to hold a minimum level of capital to guarantee their ability to absorb losses arising from borrower defaults. However, these rules have not prevented a proliferation of banking crises, nor the outbreak of the systemic crisis of 2008 (see our fact sheet on prudential regulation). On the contrary, they had the perverse effect of leading some banks to securitize loans so as not to keep them on their balance sheet, thereby reducing their incentives to analyze credit risk properly. This perverse mechanism was at the heart of the 2008 crisis.

Disarming public authorities

Cette période de libéralisation financière est également marquée par la mise sur le marché de la dette publique. Les divers mécanismes permettant jusque-là de financer à faible coût les déficits publics sont supprimés. Les États dispendieux doivent se soumettre à la « saine » discipline du marché (voir le module sur la monnaie). S’installe progressivement « l’ordre de la dette » 16 tandis que se développe une activité intense d’émissions obligataires, source de commissions pour les banques et d’actifs « sûrs » (les obligations émises par les États) pour les investisseurs financiers.

Lastly, this period coincided with an evolution in doctrine concerning the governance and missions of central banks, as well as the role of monetary policy. On the one hand, the role of central banks was now confined to monetary stability (the fight against inflation). It wasn’t until their decisive intervention during the 2008 crisis that the objective of financial stability returned to the heart of their missions. On the other hand, the model of independent central banks became widespread, on the grounds that governments’ inflation targets were insufficiently credible, as they were marked by time inconsistencies (linked in particular to their desire to win re-election).

Financial activity is at the root of cycles and crises that are harmful to society and the environment.

On doit à Hyman Minsky d’avoir bien mis en évidence le caractère intrinsèquement instable de la finance libéralisée 17. Après une période de croissance, les investisseurs commencent à prendre des risques de plus en plus élevés alors que les prêteurs sont de moins en moins prudents. S’enclenche alors une phase où renchérissement des actifs et expansion rapide du crédit se renforcent mutuellement, mettant en péril la stabilité du système (voir ci-après). On appelle parfois “moment Minsky” le point où les investisseurs surendettés sont contraints de vendre en masse leurs actifs pour honorer leurs dettes, déclenchant une spirale de baisse auto-entretenue du prix des actifs et un assèchement de la liquidité. Loin d’impacter uniquement le secteur financier, les crises financières peuvent se transmettre à l’ensemble de l’économie en particulier via le surendettement et l’assèchement du crédit.

This has dramatic social consequences, with rising poverty, unemployment and inequality. They also result in a further delay in addressing the ecological emergency, as decisions in favor of transition are postponed or watered down. How can we raise taxes on energy when precariousness is on the rise and public money is lacking to compensate for its effects? How, in such a context, can economic players (local authorities, businesses and households) decide on long-term investments?

Find out more

On the mechanisms by which financial bubbles form and burst, and how they are transmitted to the productive economy:

On the social consequences of the 2008 crisis:

Private debt is at the heart of this financial instability

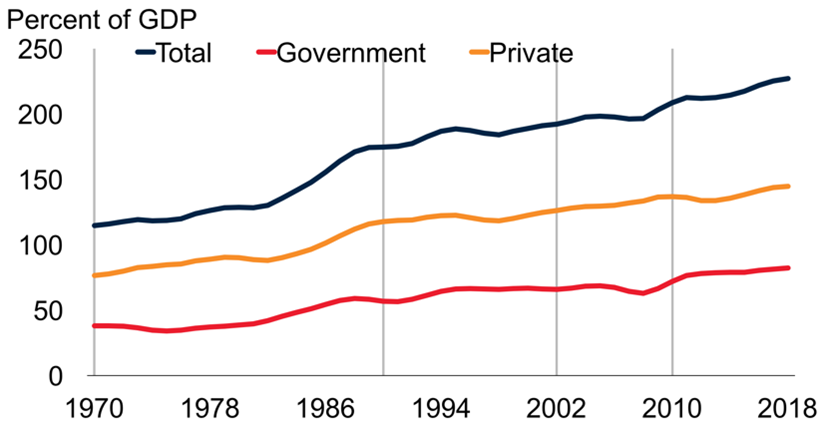

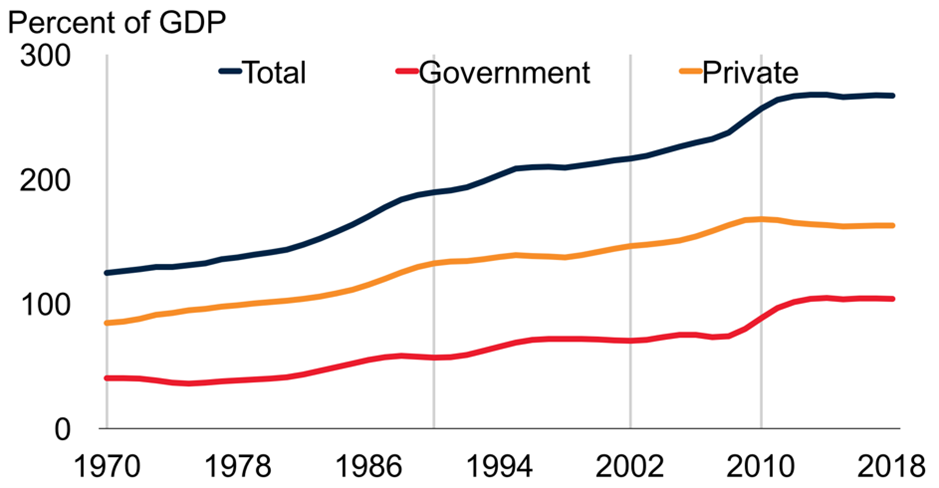

The following graphs show how debt (public and private) has risen inexorably since the 1970s. Worldwide, it rose from 114% to 227% of GDP in 2018.

This trend is even stronger in the so-called advanced countries 18 total debt reached 267% of GDP in 2018, compared with 125% in 1970.

Debt of advanced economies (as % of GDP)

Source M. A. Kose, P. Nagle, F. Ohnsorge, N. Sugawara, Global Waves of Debt: Causes and Consequences, World Bank, 2020

Si les débats se focalisent sur la dette publique, la dette privée (celle des ménages et des entreprises non financières) est bien plus importante. Dans les années qui précèdent la crise financière de 2007-2008, que ce soit au niveau global ou dans les économies avancées, son niveau est plus du double de celui de la dette publique. L’écart s’est réduit depuis, notamment parce que les États ont assumé une large part des conséquences de la crise que ce soit en soutenant le secteur financier ou en supportant les dégâts sociaux de la crise.

The importance of private debt is of great concern, as the root cause of both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the crisis of 2007-2008 was the bursting of a debt-financed speculative bubble. Rising debt and speculative bubbles go hand in hand. One of the main reasons for this is that loans are granted with “collateral” that is in fact speculative (real estate or financial securities). The supply of and demand for debt are both increasing functions of expectations of rising asset prices. In this mechanism, there is no restoring force. Credit providers feel protected by the rising financial value of collateral (speculative asset). Credit seekers, always on the lookout for added value, increase their demand for debt as speculative bubbles develop.

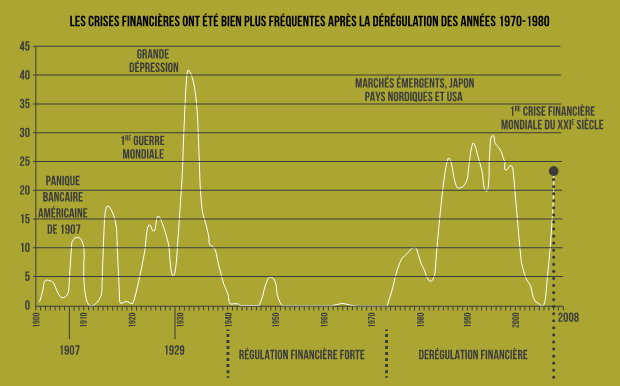

A strong correlation between the banking crisis and financial liberalization

From a factual point of view, there is a strong correlation between the number of banking and financial crises and periods of financial liberalization, as shown in the following graph:

Proportion of countries having experienced a banking crisis (weighted by each country’s weight in world GDP) over the period 1900-2008

This graph illustrates the incidence of banking crises among the sample of 66 countries (representing around 90% of global GDP) used in Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s study. Each country is weighted according to its share of global GDP, to provide a measure of the “global” impact of local banking crises. We can see that there were virtually no crises in the period following the Second World War, and that they increased significantly from the late 1970s onwards.

Source “La finance aux citoyens”, Secours Catholique – Caritas France, 2018. Original chart is from Carmen M Reinhart, Kenneth S Rogoff, Banking crises: an equal opportunity menace, Working Paper, NBER, 2008.

Financialization has many negative consequences for the economy

As we saw in Essentiel 4, the intrinsically unstable nature of finance is a source of crises that reverberate throughout the economy, with dramatic social consequences. On the ecological front, financial and economic crises have most often resulted in a delay in the necessary transition to a low-carbon economy. At a time of mass unemployment and massive indebtedness, the investments needed for the transition and environmental regulations are being postponed (or even scaled back in the case of regulations) on the grounds that priority should be given to employment, recovery and growth.

As we shall see, beyond this periodic destabilization of the economy, financialization also has other negative impacts.

Companies’ shorter time horizons

The financialization of the economy has been accompanied by the widespread adoption of a management model for listed companies aimed atmaximizing shareholder value. According to this doctrine, the interests of shareholders, seen as the owners of the company, take precedence over those of all other stakeholders (employees, suppliers, customers, etc.). Executives and managers, whose interests are aligned with those of shareholders via various mechanisms (bonuses, stock options), must first and foremost pursue the objective of maximizing return on equity (ROE). To achieve this, they adopt a variety of practices aimed at increasing dividend payouts and boosting share prices: focusing on cost reduction, limiting investment (tangible or intangible _R&D), increasing debt leverage, share buy-backs.

This form of corporate governance diverts profit from productive investment, while increasing the company’s financial fragility through growing indebtedness. It also leads to a decline in the share of wages in value added, due to the focus on cost reduction and the weakening of employees’ collective bargaining power. According to the OECD, over the period from 1990 to 2009, the share of labor compensation in national income fell in 26 of the 30 advanced countries for which data were available 19. The median labor share of national income in all these countries fell considerably, from 66.1% to 61.7%.

Changes in the balance of power within the company

Afin de réduire le coût du travail, un mouvement d’extériorisation de nombreuses fonctions de gestion de l’entreprise a été initié dans les années 1980-90 et favorisé par les nouvelles technologies de l’information et des communications. Cela a conduit à un changement radical de la structure des grandes entreprises : elles sont passées d’une structure pyramidale à une structure en réseaux où un centre de coordination peut diriger en temps réel une multiplicité de centres de profits répartis dans le monde. Cette évolution a considérablement renforcé le pouvoir des élites dirigeantes des entreprises (en particulier des directions financières) en annihilant les contre-pouvoirs internes, mais également en modifiant les rapports de force avec les États, dans la mesure où ce type de structuration de groupe permet aux firmes multinationales de mettre en œuvre des stratégies d’optimisation, d’évitement et d’évasion fiscales particulièrement performantes.

Thus, the financialization of corporate management, with the shift in the 80s to a mode of governance based on maximizing shareholder value coupled with the rise of financial institutions 20 focused on generating short-term profits for shareholders, managers generally neglect measures and investments aimed at the company’s long-term profitability and even viability.

Needless to say, this also applies to ecological and climate transition strategies, which require projections into the future and substantial investments to decarbonize or even reorient the company’s activities. This short-termist logic is not limited to listed companies: because of the market power of multinationals, it spreads to the rest of the economy via the chain of suppliers and subcontractors.

Finally, it should be noted that this model of the financialized company is also partly responsible for the increase in private debt. Companies take on debt to support their shareholders’ financial returns, or to buy back their own shares, even if this means jeopardizing their very survival; households take on debt to support their consumption in a context of stagnating purchasing power, partly created by the dogma of shareholder value; the financial sector itself and speculators take on debt to take advantage of the speculative opportunities offered by a hypertrophied, globalized financial system.

Rising income inequality

The increase in income inequality over recent decades is well documented. A number of factors have contributed to this: less progressive tax policies, globalization which has exerted downward pressure on incomes in advanced countries (due to competition from low-wage countries), the pursuit of automation and the start of robotization… Financialization has played its part through various channels:

-Income from financial activities is on average higher than in other sectors, sometimes reaching astronomical levels, as in the case of traders. This point no longer needs to be made, as studies on the subject abound. 21.

-Une autre source d’inégalité liée à la finance est liée à l’accès inégal au crédit et aux services financiers : les plus hauts revenus ont un accès facile au crédit ce qui leur permet d’exploiter les opportunités d’investissement qu’ils détectent ; les bulles financières et immobilières contribuent tant qu’elles durent à accroitre les revenus tirés du patrimoine (loyers, dividendes, plus-values lors de la cession d’actifs, intérêts perçues) ; les ménages les plus aisés ont les moyens de recourir à des experts afin « d’optimiser » leurs impôts voire de frauder le fisc, ce qui en retour réduit les recettes et donc les capacités de redistribution des États. A l’autre extrême de la distribution des revenus, l’endettement peut être un facteur d’enlisement dans les trappes à pauvreté. Contrairement aux hauts revenus, le recours au crédit des ménages pauvres n’a pas pour finalité l’exploitation d’opportunités d’investissement et donc d’enrichissement. Ces ménages ont vu leurs revenus stagner ou régresser notamment du fait de l’avènement de la valeur actionnariale comme principe de gestion des entreprises (voir le point précédent) et de la hausse des dépenses de logement (conséquence des bulles immobilières). Le crédit à ces ménages permet aux producteurs d’écouler leur production. A court terme, il permet aux ménages de « faire face » mais à long terme, le poids des intérêts les pénalise encore plus.

-Enfin, la financiarisation augmente la pauvreté et les inégalités du fait de l’impact des crises financières sur l’économie (avec notamment la hausse du chômage, et plus généralement du sous-emploi) et sur les finances publiques. Les inégalités de revenus des ménages des pays de l’OCDE (avant impôt et transferts) mesurées par l’indice de GINI ont ainsi augmenté de 1,4% sur la période 2007-2010 22. Les actions des États pour sauver le système financier et les conséquences de la crise sur les finances publiques (baisse des rentrées fiscales, hausse des dépenses sociales) se sont traduites par l’accroissement considérable des dettes publiques. Dans les pays contraints en matière budgétaire, tels ceux de l’Union européenne, le niveau de la dette a justifié très tôt la mise en œuvre de politiques de rigueur aux conséquences sociales désastreuses via par exemple la baisse de la qualité des services publics (voire un désengagement de l’Etat) affectant en premier lieu les populations les plus démunies. Notons que cette austérité s’est révélée contreproductive quant à son objectif premier : la baisse de la dette (voir notre fiche sur le multiplicateur budgétaire ).

The detour of financial activity from the real economy

As noted in Essentials 1, the banking and financial sector is expected to provide services to all other sectors of the economy. Economics textbooks generally describe banks as lending to support activity and finance new investment.

However, the financialization of the economy is changing all this. Adair Turner, former head of the UK’s Financial Supervision Authority, points out that in today’s banking systems, most loans do not finance real new investments, but the purchase of existing assets, whether real estate or financial securities (on the “secondary market”, see Essentiel 1). 23. Credit excesses do not therefore reflect over-financing of productive activity, but rather fuel bubbles.

Credit can also fuel over-investment in certain sectors. In the heart of Europe, Ireland and Spain suffered cruelly from such over-investment in real estate in the pre-crisis period, leaving the countries bereft, socially damaged by the bankruptcies of builders and developers and the resulting unemployment, banks gorged with bad debts, and a territory blighted by ghost-buildings that can’t find buyers and have often been halted before completion.

Bad loans are therefore those that do not finance useful investments. Adair Turner points out that in Great Britain, in 2012, of the 1,600 billion in outstanding bank loans to non-financial players, only 14% went towards productive business investment. The rest went to office property (14%), residential property (65%) and household consumption (7%). This is the general trend in advanced economies (see the Money module).

Savings are also massively channelled into the purchase of existing assets on secondary markets. In so doing, they contribute to the liquidity of securities and thus to the success of primary market issues, but do not provide new financing for the real economy. This is all the more true when savings or credit are used to speculate on derivatives. Finally, as we saw above, the financialization of the economy has been accompanied by the spread of the shareholder value management standard, which subjects companies to an arbitrary standard of financial return to satisfy shareholders, sometimes to the detriment of their long-term viability.

Volatile financial markets prevent the “price signal” from reflecting changes in the scarcity of raw materials

For a number of products, “derivatives” have been progressively invented which “complete” the market, thus contributing, from the doxa’s point of view, to improving the functioning of said market. It is possible to buy a barrel of oil futures, a call (or put) option on that barrel, and then a host of “derivatives”, the imagination being limitless in this area.

Contrary to the initial idea of stabilization, price volatility on these financialized markets has, on average, increased. The risks of banking, monetary and financial crises have increased. This is clearly not in the interests of manufacturers and farmers, who are seeking to protect themselves from this volatility.

As a result, the price signal observed on these markets has become blurred and, contrary to popular belief, no longer provides information on quantities. Take oil, for example. Its price peaked in 2008 at $140, only to fall back to less than $60 a few months later. Clearly, during this period, neither proven oil reserves nor global production capacity changed substantially. The price per barrel therefore provides no information on the physical realities of the market. It does, however, provide information on the instantaneous mood of the markets?

That’s why mathematician Nicolas Bouleau describes markets as “smoke and mirrors “. As he shows, it is also possible that, for purely mathematical reasons, the price of a raw material could collapse even though its resources are close to exhaustion.

So, if we want to guard against the risk of exhaustion, it’s up to public authorities to build up and communicate quality information on the physical realities of strategic markets.

Find out more

- Nicolas Bouleau, “Future world prices for exhaustible resources”, Knowledge and Pluralism blog, 2013

- Nicolas Bouleau, “The price of the planet”, La vie des idées, 2018

- Nicolas Bouleau, “Why speculation prevents the ecological transition” (video), blog Connaissance et pluralisme, 2013

- Gaël Giraud, “Le pétrole, un exemple de prix volatile et imprévisible aux conséquences majeures” (video), MOOC Transitions énergétiques et écologiques dans les pays du Sud, ENS

Rising commodity price volatility and large-scale social crises in developing countries

As early as the end of the 19th century, specialized markets (mostly located in London and Chicago) were established. Cereals, rice, soybeans, cocoa, copper, nickel, rare earths and precious metals… are traded on financial markets where financial and non-financial players negotiate not only physical products (the underlyings), but increasingly contracts and ” derivatives “. While some players might have hoped for price control, or at least a degree of stability and reduced volatility, the opposite is true. The consequences are unfortunately very real, and harmful to the most disadvantaged. Take, for example, the “bread riots” in Egypt, following the doubling of wheat prices between April 2007 and April 2008, from 5 to 10 dollars a bushel, a doubling that was not justified by any shortage. At the same time, we witnessed a 20-fold increase in futures contracts held between 2003 and 2008, from $13 billion to $260. While this is not absolute proof of causality (of the effect of financialization on price rises, or at least of their greater volatility), it is, on the contrary, clear evidence of the absence of a stabilizing effect.

As Ivar Ekeland and Jean-Charles Rochet note in their book, the U.S. Congress tried, unsuccessfully, to remedy this situation in 2010 24.

“The Dodd-Franck Act calls on the Commodities futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to impose limits on speculative positions in commodities (also including metals oil and gas) when it deems speculation in these markets “excessive”. The rule was adopted on October 18, 2011, despite intensive lobbying by the financial industry. It was immediately attacked by two trade associations (ISDA and SIFMA), who argued that the CFTC had failed to conduct a prior cost-benefit analysis showing that its new rule would be beneficial. On September 28, 2012, a federal judge sided with the financial industry and struck down the new rule adopted by the CFTC on the grounds that it had presented no quantitative or empirical analysis showing that the new regulation would benefit the market! 25 Triumph of finance: the judge no longer takes the citizen’s point of view, but the market’s!”

Source “La finance au service du citoyen”, Secours catholique-Caritas France report, 2018.

The risk of a new systemic financial crisis still exists

In the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, the firmness of public statements 26 made it possible to envisage a real return to financial control. A decade later, after intense negotiations with the banking industry in all the world’s major countries, measures have certainly been adopted to reduce the risks taken by financial players. But, as the many studies published to mark the tenth anniversary of the crisis underline 27these measures are far from sufficient to protect the economy from another banking and financial crisis.

“This time it’s different

On September 21, 2015, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England denounced in a remarkable speech 28three widely held preconceptions about finance. “This time it’s different 29 is the first of these preconceptions.

This expression refers to the conviction, repeated over and over again in history, that this time the economy will escape a financial crisis. It refers to this collective blindness and the certainty that this time the financial euphoria has a sound basis. The good health of finance is merely a mirror image of the good performance of the real economy.

In the name of this conviction, in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, we believed that controlling inflation was the guarantee of financial stability, and we allowed private debt to grow indiscriminately. Financial innovations such as securitization, structured finance products and derivatives both boosted and stimulated the destabilizing drift of credit. As Adair Turner points out: “In the pre-crisis years, economic orthodoxy was characterized by anathema to government money creation and a totally relaxed attitude to the level of private debt created by the markets. The latter led to a disaster from which many ordinary citizens around the world are still suffering.” 30

The 2008 financial crisis put systemic risk back at the center of public authorities’ attention.

This expression refers to the fact that a particular event causes a chain reaction of negative effects on the entire financial system, culminating in its collapse. It is all the more serious because the impact is not limited to the financial sphere, but spreads to the rest of the economy.

The 2008 crisis highlights the two dimensions of systemic risk.

La dimension transversale est liée à l’interdépendance entre les institutions financières. Tous les secteurs économiques ne sont pas soumis à un risque de contagion : par exemple, si un grand fabricant automobile comme Renault fait faillite, cela n’a aucune raison d’entraîner la faillite de son concurrent Peugeot, bien au contraire. Pour les banques (et plus généralement les acteurs financiers), il en va différemment. Elles ont ceci de particulier qu’elles se prêtent massivement entre elles. Ainsi, la faillite d’une très grosse banque peut provoquer par contagion celles d’autres établissements financiers puisque ces derniers devront assumer des pertes sur des actifs qui n’étaient à priori pas considérés comme risqués (et pour lesquels ils n’avaient donc pas mis suffisamment de fonds propres en regard). C’est ainsi que la crise immobilière aux États-Unis, provoquée par les défauts des emprunteurs « subprimes », qui aurait pu rester locale, s’est transmise à l’ensemble du système financier mondial via la faillite d’une très grande banque, Lehman Brothers.

The temporal dimension is linked to the procyclical nature of players’ behavior: as the financial cycle rises, risk increases as agents take on debt and invest, following a bubble-forming logic in which rising asset prices and debt are self-perpetuating (see l’Essentiel 4 and our fact sheet on Minsky and Fisher ); conversely, in the downturn of the financial cycle, rational behavior at the microeconomic level (stopping lending to other potentially insolvent players, selling supposedly risky assets or to free up financial resources or before prices fall too far) deepens the crisis at the global level (collapse of asset prices, liquidity crisis).

Despite public regulation, the face of the global financial system has not fundamentally changed

Without going into the details of post-crisis financial regulations, we will simply highlight a few figures which show that the financial sector does not seem to have turned any significant corner.

The financial system has continued to grow and still represents around 500% of GDP. It remains as concentrated and interconnected as ever (see Essentiel 8). The shadow banking “remains as important as ever, and is no longer regulated. There are still 30 systemic banks, and even if they are better capitalized than before the financial crisis, this does not guarantee that they could cope with a new global crisis without help from the public authorities.

In short, systemic risk is present in its cross-functional dimension.

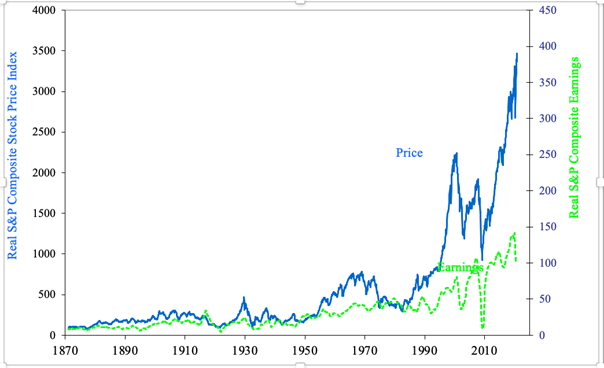

As for the time dimension, you only have to look at the levels reached by the equity and real estate markets to realize the financial euphoria underway.

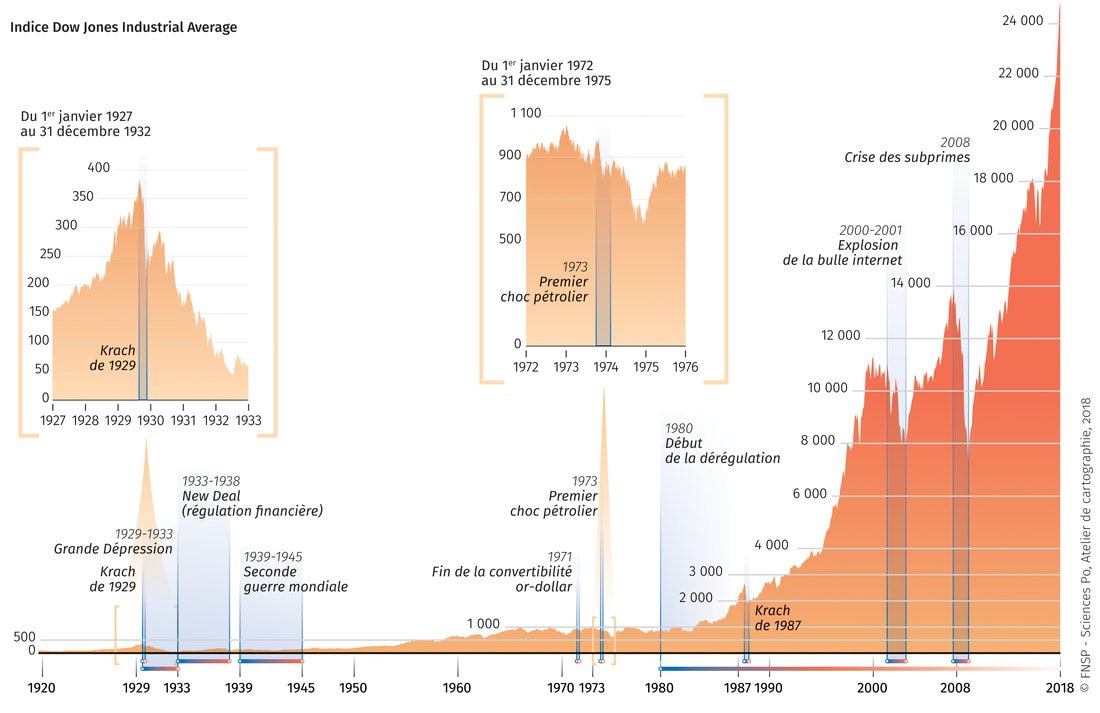

Stock market valuations are reaching record levels, as shown by the following chart tracing the long history of the Dow Jones index (see also here for the S&P500, here for the Nasdaq, here for the Stock Europe 600).

Dans de nombreux pays l’immobilier a rattrapé voir dépassé son niveau de 2007. C’est par exemple le cas aux États-Unis, en France, au Royaume Uni ou en Allemagne.

It is impossible to predict when a crisis will erupt, or how deep it will go, how long it will last, or what its economic consequences will be. All we can say is that the financial system is still a long way from a state where any risk of crisis is eliminated or becomes highly unlikely.

However, there is a fundamental difference between the current period and the pre-2008 period: banks and financial markets are on a drip-feed of liquidity from central banks. The financial system is kept weightless, and continues to boom despite the economic crisis linked to the measures taken to deal with the COVID 19 pandemic. It is no longer just the indebtedness of private players (households and companies) and financial players that is fuelling the bubbles, but the monetary policy pursued by central banks.

One final point: the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted a new reality at the start of the 21st century: the sources of destabilization in the financial system can come from our natural environment. This realization is not entirely new: back in 2015, the systemic risks posed by climate disruption to financial activity were identified by Mark Carney in his now-famous “tragedy of the horizons” speech(see next point).

Climate is a source of proven systemic risks

In September 2015, in a speech delivered at Lloyd’s headquarters, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board 5stated that global warming poses risks with potentially systemic financial consequences.

He introduces the concept of the “tragedy of horizons”. The gap between the short-term horizons of financial players and the long-term horizons of climate impacts means that financial players are unable to identify the risks they run as a result of global warming. It also draws up a typology of these risks.

Following this seminal speech, central banks around the world took up the subject. As a result, the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for the Greening of Finance was created at the end of 2017. It aims to develop and promote methodologies to better identify and measure the financial sector’s exposure to climate risk, to draw up climate stress tests, but also to promote financing for the transition to a low-carbon economy. To date, however, supervisors’ attention has focused much more on risk measurement than on adapting monetary and prudential policies to combat global warming(see the module on money).

Physical risks: insurance and investor exposure to the physical consequences of global warming

Global warming generates “extreme” meteorological events (cyclones, heatwaves, intense rainfall events, etc.), i.e. those that statistically significantly exceed historically observed reference levels. It also manifests itself in profound changes to the natural environment, such as rising sea levels or the melting of continental glaciers (which feed the planet’s major rivers). Physical risks concern the destruction of asset stocks (due to forest fires, floods, cyclones, rising oceans, etc.), the reduced profitability of exposed companies and/or the deterioration of income streams (impact on tourism, fishing, harvests or the incomes of workers in the areas concerned, disruption of production chains, etc.). This physical damage can directly affect the longevity of capital and accelerate its depreciation. The direct impact on financial stability comes via the often cumulative and highly correlated losses of insurers and reinsurers, but also via other transmission belts that are sometimes just as direct, such as lending channels or bank investments. These physical risks will generate feedback and contagion effects between sectors and regions that are very difficult to quantify.

Transition risks: the economic and financial consequences of reducing greenhouse gas emissions

Reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions can result from the implementation or mere announcement of low-carbon policies (carbon tax, banning certain polluting vehicles from city centers, ambitious trajectory to increase the share of renewable energies in the energy mix, etc.), from a technological breakthrough making a rapid transition possible, or from a shift in individual preferences and social norms. In all cases, economic activities are affected more or less strongly and rapidly. In financial terms, the most feared transition risk is that of a sudden adjustment in asset prices.

The polarization of market expectations in response to such changes in climate policy, technology or behavior can lead to a sharp depreciation of assets backed by high-carbon activities (e.g. fossil fuel exploitation), with chain effects that are difficult to assess. These assets are known as stranded assets, in the sense that they are backed by investments that have lost all or part of their value before the end of their economic life, due to unforeseen regulatory or technological developments.

The difficult trade-off between physical risk and transition risk

Rapid decarbonization of the economy means short-term materialization of the transition risk, but long-term mitigation of the physical risk. If a rapid low-carbon transition in line with the Paris Agreement commitments were to be implemented, a large proportion of existing infrastructure, industrial plants and machinery would have to be scrapped or entirely converted. Fossil fuel extraction and transportation infrastructures would be the first to be affected, but many industrial facilities upstream and downstream of fossil fuel combustion would also be heavily impacted. Companies owning or operating these assets or infrastructures would be severely penalized economically, as would their bankers and investors.

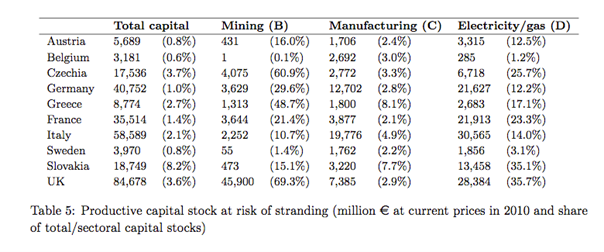

Le tableau suivant est issu d’un article paru en 2019 32 dans lequel les auteurs ont réalisé pour un certain nombre de pays européens une analyse empirique systémique des stocks de capital productif exposés au risque d’échouage via notamment les effets de cascade dues aux interdépendances sectorielles. Comme on peut le constater, les pertes peuvent représenter des portions très conséquentes des secteurs analysés.

Le lien entre les politiques publiques en faveur du climat et la concrétisation directe du risque de transition complique considérablement les prises de décision publique. En effet, une politique publique climatique menant à une dépréciation massive et généralisée d’actifs carbonés se manifesterait à court terme par une crise financière systémique alors que les effets sur le climat ne se feront sentir qu’à horizon de plusieurs dizaines d’années 33. C’est une des manifestations de la tragédie des horizons.

This is also a challenge for central banks. In the event of a climate-related financial crisis affecting the solvency of banks and insurance companies, central banks will be under massive pressure to buy assets impaired by physical and transitional risks. They will then be, against their will, climate loss absorbers of last resort rather than mere lenders of last resort.

Liability risks

These risks concern legal action taken by victims of natural disasters attributable to climate change to seek compensation from those they hold responsible. Such proceedings can hit carbon-based industries and their insurers hard. These lawsuits can damage the reputation and solvency of the companies concerned, and even bankrupt them (see box).

The bankruptcy of Pacific Gas & Electric

Following devastating fires in California, Pacific Gas & Electric was indicted for negligence. Estimating that it would have to pay nearly 30 billion in damages, the company, unable to meet its obligations, filed for Chapter 11 protection, which temporarily protects it from its creditors. Stock market collapse, losses for holders of bonds issued by the company and for their insurers: the mechanisms for transforming legal risk into financial risk are fairly straightforward, although difficult to quantify.

Source PG&E: The First Climate-Change Bankruptcy, Probably Not the Last, Wall Street Journal, 2019

Find out more

- This section draws heavily on the article by Laurence Scialom, “Les banques centrales au défi de la transition écologique. In praise of plasticity”, La Revue Economique, 2022/02

- Mark Carney’s speech, “Breaking the tragedy of the horizon – Climate change and financial stability”, London, 2015.

- The website of the network of central banks and supervisors for the greening of finance

- Patrick Bolton et alii, “The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change”, Bank for International Settlements, Banque de France, 2020

The banking and financial system is too concentrated

The free movement of capital and the decompartmentalization of banking and financial activities have led to financial globalization: financial activities and players have taken on a cross-border or even international dimension, giving rise to financial multinationals with dominant positions in virtually every segment of the banking and financial services market.

This is particularly evident in the banking sector. Since 2011, the Financial Stability Board 5 has maintained a list of so-called systemic banks, known as G-SIBs (Global Systemically Important Banks). Since 2016, there have been 30 of these banks, whose failure would be likely to cause a contagious collapse of the international financial system as a whole. According to the Global Capital Index of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (one of the US regulatory bodies), these 30 systemic banking groups weighed in at over $53,000 billion at the end of 2017 (aggregate balance sheet size), or almost 53% of global banking assets (which , according to the Financial Stability Board, totalled over $141,000 billion in 2017).

D’après l’économiste François Morin35, quatre de ces groupes (Deutsche Bank, Citigroup, Barclays, UBS) concentraient 50 % des transactions sur le marché des changes en 2015 (dix concentrant 80 % des opérations). Quatorze d’entre eux appartenaient aux dix-huit groupes constituant le panel du Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate), les mettant en position d’influencer la principale référence du marché pour déterminer le prix de l’argent à très court terme. Ces groupes sont également en position dominante sur le marché de la dette publique en tant qu’intermédiaires entre les États émetteurs et les investisseurs acquéreurs de titres publics.

Cette concentration n’est pas immuable : elle est le fruit d’une histoire comme on peut le constater en regardant par exemple l’évolution de la concentration des actifs bancaires aux États-Unis sur une longue période en fonction de la taille des groupes.

Concentration of banking assets

Source Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), one of the US regulatory bodies.

Comme le notent Jézabel Couppey Soubeyran et Gunther Capelle-Blancard, « la taille des établissements et la concentration du marché qui l’accompagne résultent, au moins en partie, d’une logique bien spécifique au secteur bancaire. Une plus grande taille permet généralement à une entreprise de bénéficier d’économies d’échelle et d’offrir une plus large gamme de services. » La taille facilite aussi la collecte d’informations qui jouent un rôle crucial sur les marchés. L’essentiel des flux financiers transite par ces groupes (voir plus haut la part des volumes sur le marché des changes) qui exploitent bien sûr cette position dominante. Ces informations ne sont pas publiques, ce qui crée clairement une asymétrie entre acteurs. « Mais outre ces arguments traditionnels, les banques ont tout intérêt à accroître le plus possible la taille de leur bilan afin de bénéficier, implicitement, de la garantie de l’État en cas de difficultés financières : c’est le fameux problème d’aléa moral du too big to fail auquel tentent de remédier les dispositifs de résolution des défaillances bancaires mis en place dans le cadre de l’Union bancaire en Europe ou de la loi Dodd-Frank aux États-Unis. Reconnaissons aussi que les États, notamment en Europe, n’ont jamais vraiment cherché à limiter la taille des établissements et ont, au contraire, plutôt encouragé les rapprochements afin de constituer des “champions nationaux” dans un contexte de concurrence entre les places financières. »

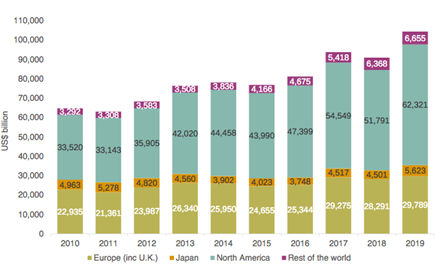

Beyond the banking sector itself, recent decades have also seen the development of collective savings management. Individuals are managing their financial assets less and less directly, entrusting them to professional institutional investors (notably pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds). These players have grown considerably in importance since the 1980s, in line with the financialization of the economy. For example, the assets managed by insurance companies, which amounted to some $519 billion in 1980, will reach $34,000 billion in 2019. For pension funds, the figure has risen over the same period from $860 billion to $39,000 billion. Beyond this explosion in assets under management, these sectors are also highly concentrated, as demonstrated, for example, by the fact that the FSB is also developing indicators to identify systemic insurers (even if this is being done with a delay compared to the work of a similar nature done for the banking sector).

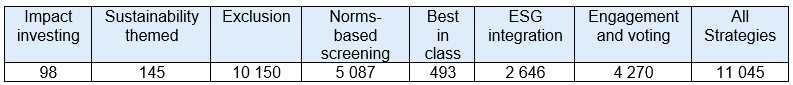

Finally, the asset management sector is emblematic of this concentration in the financial sector. Assets under management have almost doubled in less than 10 years, reaching $104.4 trillion at the end of 2019.

Total assets under management of the world’s top 500 asset managers (see Essentiel 1)

Source The world’s largest 500 asset managers, Thinking Ahead Institute, 2020

This sector is characterized by hyper-concentration at the top: Black Rock, the largest, managed $7,800 billion in assets in 2020. The top 20 asset managers account for 43% of funds under management.

Comme le souligne l’économiste Olivier Passet : « À eux seuls, BlackRock, Vanguard et State Street contrôlent 25 % des droits de vote des 500 principaux groupes cotés américains et gèrent 10% de la capitalisation boursière mondiale. La gouvernance actionnariale est sous tutelle de mastodontes planétaires que la crise a propulsés encore plus haut. »

Les paradis fiscaux sont une source inacceptable de pertes fiscales pour les États

Tax havens are countries or territories in which certain taxes are very low or non-existent and which are characterized by a high degree of opacity. 36. Their importance has grown with financial globalization. The free movement of capital has reduced controls and facilitated the movement of capital, including for tax evasion purposes (and, of course, money laundering). Financial institutions and law firms established in these countries offer their services to wealthy individuals and multinationals from all over the world. You only have to try to understand offshore schemes to see just how sophisticated the financial techniques used are.

A few definitions

Tax evasion: A strategy for avoiding taxes by placing some or all of one’s assets in low-tax countries, without expatriating there. Tax avoidance can be either tax optimization (legal) or tax evasion (illegal).

Tax optimization: The use of legal means to reduce or even avoid tax liability. It requires a good knowledge of the law and its loopholes. It is practiced by both individuals and companies, often multinationals.

Tax fraud: The use of illegal means to reduce or evade taxes. Moving capital to foreign jurisdictions without notifying the tax authorities is a form of tax fraud.

Source These definitions are taken from the Lexique des Paradise Papers available on the Le Monde.fr website .

Tax evasion (see box) has become better known and understood since the proliferation of cases, investigations and revelations that followed the 2008 crisis. 37. These led to the mobilization of several countries and international bodies to collect data on a phenomenon that had previously been largely opaque 38.

Un manque à gagner très conséquent pour les États

In their research Missing Profits, published in 2022, economists Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier and Gabriel Zucman estimate that, on a global scale, “almost 40% of multinationals’ profits (nearly $1,000 billion in 2019) are hidden in tax havens every year”. For France, this represents a loss of tax revenue of over $13 billion.

Gabriel Zucman also estimates that the wealth of individuals hidden in tax havens “costs” governments $155 billion a year. “Almost half of the wealth relocated to tax havens belongs to the wealthiest 0.01% of the population in wealthy countries. In the UK, Spain and France, around 30% to 40% of the wealth of these households is domiciled abroad.”

In this respect, the European Union is in a difficult position: on the one hand, increased competition between countries since the 1980s has led to a radical drop in corporate tax rates, from an average of 49% to 24% in 2018. On the other hand, and above all, since its creation, it has been home to tax havens such as Luxembourg and Ireland, without wishing to acknowledge it.

Banks are at the heart of the process, not only by facilitating their customers’ tax avoidance practices, but also by locating their own profits in tax havens. A study shows that in 2015, tax havens accounted for 18% of the foreign sales and 29% of the foreign profits of the 36 biggest banks, compared with just 9% of the workforce they employ abroad 39. These figures clearly show that a significant proportion of their business and profits are artificially transferred there.

Tax evasion is a major factor in increasing inequality

Clearly, it’s the wealthiest individuals who benefit the most, whether directly by avoiding taxes, or indirectly through the higher profits of the companies whose shares they own. On the other hand, the loss of tax revenue has to be compensated either by raising taxes on the middle classes, or by cutting public spending (and therefore public services accessible to all citizens). Scandals and revelations are therefore also a source of growing social protest: when governments want to cut public spending or raise taxes, in the name of budgetary rigor, tax evasion comes as an even greater shock. Finally, tax havens lead us to underestimate the level and growth of global inequality. Wealth invested in tax havens disappears from the statistical radar, and in particular from national accounts and tax returns.

Find out more

Markets won’t finance the ecological transition on their own

Facing up to the ecological and social challenges of the 21st century implies a profound transformation of our development model in order to distribute resources more equitably, drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, save natural resources, depollute water and rehabilitate soil.

To achieve this, we need to invest massively in new infrastructures where they are lacking, and in bringing existing ones into line with ecological standards. Transport, energy and water infrastructures, fleets of vehicles, aircraft and ships, fleets of buildings, stocks of machinery: it’s our entire stock of physical capital, our entire economic heritage, that needs to be renovated, restructured and sometimes even destroyed to limit the exploitation of natural resources and GHG emissions. We also need to invest in education, training and R&D, in order to support the professional transition of those working today in activities such as the fossil fuel industries, which will not be able to continue if the transition takes place.

As a result, the financial requirements are extremely substantial, amounting to trillions of dollars worldwide. Many are betting on green finance, i.e. on the fact that investors will make their investments according to ecological criteria, notably due to regulatory developments such as the obligation to disclose the environmental impact of financing.

A number of factors cast doubt on the ability of the financial markets alone to finance the ecological transition.

Financial markets are driven by the search for short-term returns

Firstly, given the current state of the capital markets, it is highly unlikely that public interest considerations will take precedence over the short-term return objectives of financial players. As noted in Essentiel 4, the vast majority of the financial system is 40less focused on financing new investments than on buying existing assets (i.e. on the secondary market) with a view to generating capital gains through rising asset prices.

These are the words of the experts of the High Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (HLEG), mandated by the European Commission to make proposals for the implementation of a Europe-wide sustainable finance strategy. “Strategic frameworks and market behaviors continue to favor a focus on liquid assets, short-term financial instruments and returns, and low-profitability debt in a low-interest-rate environment. On the other hand, investments in infrastructure, small-cap indices, SMEs, tritrisation, private equity and real assets are more limited. Yet these assets are often critical to the transition to sustainable development. 41.

Changing these short-termist practices would require far more far-reaching regulatory and tax changes than have been implemented to date. For example, measures would need to be taken to reduce purely speculative investments and leverage.

Moreover, it’s not just a question of putting the financial world back at the service of the productive economy, it’s also necessary to specifically target investments conducive to a low-carbon economy that consumes fewer natural resources. This would mean going far beyond current measures, which focus on extra-financial reporting by companies and financial institutions, in line with the received wisdom that well-informed markets will correctly orient financial capital (see Received wisdom 1). A much more consistent mobilization of monetary and prudential policies to integrate environmental criteria would appear to be a prerequisite for any real reorientation of financial flows. 42.

Financial markets are not suited to financing many transition projects

Even assuming that the above obstacles have been overcome, two additional characteristics of transition projects cast doubt on the wisdom of relying on capital markets alone to finance the ecological transition.

First of all, many ecological transition projects are too unprofitable or even unprofitable under current economic conditions, which do not properly value the ecological and social impacts (e.g. soil decontamination activities, developments to create ecological continuities, wetland restoration). Furthermore, some projects are profitable in the long term, but the populations concerned do not have the means to invest. This is the case, for example, of energy-efficient building renovation, which is profitable in the long term thanks to the savings made on energy bills, but whose owners or occupants are low-income households. These investments require a combination of public funding (often in the form of subsidies) and regulatory obligations. Markets are of little help.

Finally, it should be noted that a large proportion of transition project sponsors do not have access to market finance. This is the case for households who want to renovate their homes, farmers who need to radically change their practices, or non-innovative SMEs who need to renew their production tools. It’s also the case for small local authorities: the renovation of their public buildings is on the order of a few million euros, an insufficient size to reach the financial markets, which handle transactions worth at least tens of millions of euros.

Find out more

- L’illusion de la finance verte, Alain Grandjean and Julien Lefournier, Editions de l’Atelier (2021)

- Le mirage de la finance verte, Le Monde, 21/10/21

- Testimony of Tariq Fancy, former chief investment officer for sustainable investing at Blackrock

- The limits of green funds in Europe, Ademe & Novethic study (2021)

Preconceived notions

Financial markets are efficient

In 1970, Eugène Fama coined the term “market efficiency”. 43 (” efficiency market hypothesis “, EMH) and is said to have “demonstrated” that financial markets are efficient.

This expression has since been widely used, disseminated and discussed in the financial world. In particular, it has given rise to the idea that if public authorities, regulators or supervisors observe a “problem” (as in the case of climate change, which is clearly not taken into account by the financial sector, see Essentiel 7), they do not have to act on any other level than that of information. In particular, they do not have to create regulations to ensure that market players take the problem in question into account. If the right information is known to the financial markets, as they operate “efficiently”, they will play their role correctly.

Efficient is an ambiguous term. Seen from a non-specialist’s point of view, the above argument suggests that financial markets are fulfilling the mission that public opinion intuitively gives them: they allocate “capital” (to simplify, savings) efficiently, i.e. to the companies or projects that are “best” for society. However, for neo-classical economists, this idea refers to the notion of optimality as defined by Vilfredo Pareto: a situation is optimal when it is not possible to improve the situation of one actor without disadvantaging another. Clearly, the question of distribution has nothing to do with it: a situation where A has everything and B nothing, can be efficient in Pareto’s sense, which is hardly in line with common intuition, and is not without raising questions: if the “economic efficiency of markets” can lead to unfair situations, then public regulations are needed to correct them.

In any case, and this may seem strange for a theory based on a mathematical model and awarded the Nobel Prize in 2013, Fama’s use of the term “efficiency” is ambiguous, and his “demonstration” does not prove that markets are efficient in the sense of optimal allocation of savings. Yet he himself evokes this sense at the start of his seminal article:

“The very first role of the capital market is to allocate ownership of the economy’s capital stock. In general terms, the ideal is a market in which prices provide appropriate(accurate) signals for the allocation of resources”.

However, this is not the thrust of the article (nor of subsequent works). It focuses on another question, without convincingly demonstrating the link with the previous one: that of “informational” efficiency. But here, too, it is not very clear.

Robert Shiller 44who was awarded the Nobel Prize at the same time as Eugène Fama (even though he is one of the economists convinced of the inefficiency of markets…), distinguishes between three meanings:

Zero arbitrage efficiency: “no pain, no gain

This is what Eugène Fama formulated in 1991: a market is efficient if profitable forecasting is impossible for market participants. 45. This idea is taken for granted in the trading world, which takes for granted what is known as the “absence of arbitrage opportunities”: there is no financial strategy which, for zero initial cost and therefore without taking any risk, can acquire certain wealth: the future of the markets is unpredictable. Buying a financial asset in order to resell it is therefore risky… We can call this efficiency “zero arbitrage efficiency”.

This empirical finding lies at the heart of the debate between active and passive management. 46. In short, if markets were efficient (in this sense of the word), wouldn’t it be better for financial investors to entrust their funds to a “passive” manager who simply “follows” or “replicates” the market. Management fees would be lower, and results better on average… or at least less risky.

The rise of passive management is not unrelated to the widespread belief that “markets are efficient” (always in this sense). Unfortunately, it is probably in itself a source of increased systemic risk. Indeed, the alignment of investor behaviour (via the asset managers to whom they entrust their funds) as a result of this passive management can intrinsically lead to the formation of bubbles. To put it another way, this “zero arbitrage efficiency” not only cannot be confused with informational efficiency, but can also induce behaviours that make market information less efficient… So to speak of efficiency here is clearly a misuse of language.

Informational efficiency: “prices are right”.

In his 1970 text, Eugène Fama wrote: ” A market in which prices always ‘fully reflect’ available information is called ‘efficient’. ” This then led to more precise definitions, thanks to which statistical tests were constructed in an attempt to decide whether a given market was or was not strongly or weakly efficient. 47 and debate. Low efficiency means that the current price incorporates all information on past prices of the asset concerned. If this condition is satisfied, technical analysis of the historical price series cannot lead to any profit. In semi-strong efficiency, the price contains all publicly available information. The evolution of other assets cannot, through their correlations with the asset under study, provide opportunities for profit. In the case of strong efficiency, the price contains all the public or private economic information that the market has taken into account and digested, including insider knowledge.

In practical terms, this literature does not allow us to draw any clear, usable conclusions. The value of an asset is a debatable notion (unlike its price in a transaction, which is observable at a given point in time). According to standard financial theory, the value of an asset is the discounted sum of the future cashflows it generates. This definition is clear, but its practical application depends on the assumptions made about these cash flows and the discount rate. According to Fama, the financial markets would reveal this value. If this were true, it would eventually start to fluctuate sharply when a speculative bubble bursts. If the markets had been right before the bubble burst (indicating a very high value), how could they still be right afterwards (the value having become lower)? The answer is that new information may have come to light. This is indeed the case: when markets turn around, it’s because market participants’ expectations are shifting massively (and vice versa, market movements move expectations…). But does this have anything to do with the value of a given asset? We doubt it.

Before going any further, let’s emphasize two points:

1 Eugène Fama’s model is based on an assumption of “rational” behavior on the part of economic agents, which has been challenged by the work of behavioral economists (and, more generally, by most of the work in social psychology). Ironically, Robert Shiller challenged this work thanks to the use of Lars Peter Hansen’s statistical tools (the third Nobel Prize winner, in the same year as Fama and Shiller…).

2 Benoît Mandelbrot, (mathematician, inventor of fractals) has shown, based on the analysis of empirical data, that the assumption (used in Eugene Fama’s modeling and above all in most financial calculations) that movements on financial markets obey so-called “normal” or Gaussian probability laws (in other words, follow Brownian motion) is simply false. 48. This is one of the reasons why financial crises occur more often and on a greater scale than predicted by efficiency theories. This is demonstrated by the scale and repetition of financial crises since markets were freed up, decompartmentalized and deregulated (see Essentiel 3).

Finally, let’s note that there is still a huge gap to be bridged between asserting that “prices are right”, assuming that this is true, and demonstrating that markets would allocate capital correctly for the economy to be efficient (allocative efficiency), the third possible meaning of the term efficiency to which we will now return.