This text has been translated by a machine and has not been reviewed by a human yet. Apologies for any errors or approximations – do not hesitate to send us a message if you spot some!

Introduction

What counts can’t always be counted, and what can be counted doesn’t necessarily count.

Accounting is a discipline that is often regarded as austere, unappreciated and unrecognized. It is seen as a technique, with no importance other than that of correctly recording the necessary entries, a practice that is certainly useful – you have to keep your accounts properly if you want to balance them, or even make a profit – but not very exciting, and with no stakes other than practical ones.

In this module, we’ll see that accounting is much more than an auxiliary or neutral tool: it is the (often implicit) basis of many of our economic representations and reasonings, which need to be reconsidered in depth. It structures the way we see business, and the economy in general, without our being clearly aware of it. It’s a pair of glasses, a prism, that makes us see things in a certain way.

Far from being a neutral technique 1 it has been developed in response to precise objectives and by adopting conventions (and then evolving them, as we shall see with IFRS accounting standards), which are obviously debatable, and moreover discussed in specialized circles. It is very significant that the finance department, to which accounting is attached in companies (of a certain size), has, in our contemporary societies, a decisive power in the running of companies, often being held by the company’s number two.

In its current form, accounting serves shareholders and company directors. It takes neither nature nor “human capital” into account. Its reform, however far-reaching, must be launched without delay. But first, we need to understand its main ins and outs. That’s what we’re going to try to do here, without launching into an accounting course.

Definitions: company, society, stakeholders

What’s the difference between a company and a corporation?

According to Insee, a company is an entity with legal personality created for a commercial purpose, i.e. to produce goods or services for the market, which can be a source of profit or other financial gain.

The term ” company ” refers to the same type of entity in everyday language and economic literature. However, unlike “company”, this term has no legal or accounting definition. It also refers to the collective (employees) whose members have a legal link (usually subordination) with the “company” (in the legal sense).

Stakeholders

A company’s “stakeholders” are all those who have a direct relationship, monetary or otherwise, with the company: shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers, service providers and subcontractors, bankers and other lenders, the State, social organizations and local authorities, neighbors where the company is located, associations and NGOs…

The essentials

The birth of capitalism is linked to that of accounting

Along with the joint-stock company, corporate accounting is one of the two essential inventions behind the emergence of capitalism.

The history of capitalism is inextricably linked with that of private property, the law governing it and its evolution over the centuries. Capitalism has fundamentally needed a financing capacity multiplied by the use of “shares”.

The birth of the joint-stock company

The first “joint-stock” company, Société des moulins de Bazacle, was founded in 1372. The company’s shares, known as “uchaux”, were freely transferable by their holders at market price, and entitled them to dividends. 2 . In 15th-century Genoa, large companies were founded whose capital was divided into transferable shares and whose shareholders’ liability was limited to their capital outlay. A century and a half later, the first major trading companies appeared in London and Amsterdam: the English East India Company and the Dutch West India Company, with considerable capital and numerous investors.

Definition of a joint stock company

A joint-stock company is a type of company whose share capital is represented by financial securities, the shares subscribed by the associates, who are then called shareholders. These shares give their owners financial rights (through the payment of dividends, for example). 2 ) and the right to vote at the company’s Annual General Meeting. The company may or may not be listed on the stock exchange (in which case its shares may be traded “at market conditions”). In this case, the company is said to be issuing shares to the public, and its directors have additional obligations in terms of public information about the company.

In the 19th century, another major development took place with the introduction of the concept of ” limited liability “, meaning that shareholders’ liability was limited to a certain sum (usually the amount of their capital contribution). This enabled shareholders to limit their criminal and financial risks by transferring them to the company, but without sharing ownership of the shares and the accompanying pecuniary and social rights.

Accounting: an efficient and precise tool for economic development

Capitalism is also inseparable from corporate accounting 4 and… accounting law. Double-entry bookkeeping, still used today and widespread throughout the world, first appeared in Northern Italy in the 14th century (probably before the legal formalization of the company). It was codified in Europe in the 15th century. 5 by Luca Pacioli, a Venetian monk, in his work 6 devoted to the mathematical knowledge of the time. This virtually universal technique is still in use today. It has gradually been made compulsory by governments and major international institutions 7 .

Understanding double-entry bookkeeping

A company’s activities are reflected in a variety of financial flows. Double-entry bookkeeping involves recording each of these flows in two accounts simultaneously: each time one account is debited, another is credited with the same amount. This makes it possible to track financial flows according to their origin and destination.

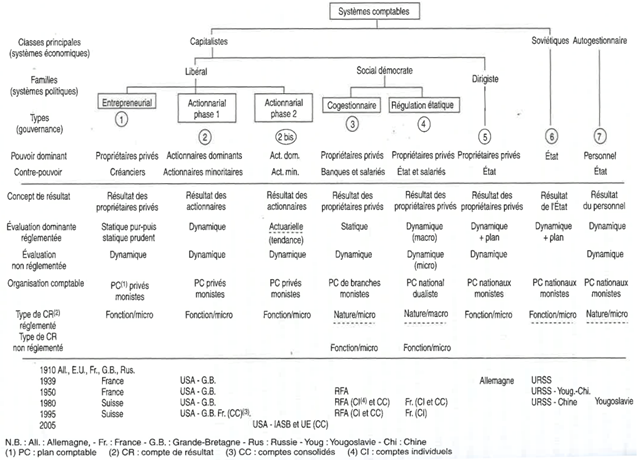

The following two examples show how :

- the fact that a shareholder subscribes to the company’s capital

- payment of a supplier by the company

The success of double-entry bookkeeping is due to many factors, the most decisive of which is the following:

Double-entry bookkeeping enables shareholders to track the use of their capital contribution

They can therefore see whether their capital has been preserved, or even increased, or whether it has been “eroded” by the company’s activities. They can then decide to pay themselves dividends. 2 to leave profits in the company (so that it can invest, for example) or, if necessary, to recapitalize it, which is legally obligatory under certain conditions.

What’s more, accounting information can tell them what their capital is “worth” (even if the value of a company’s shares cannot be deduced mechanically from the accounts). 9 .

This value is of interest to shareholders if they wish to “sell” their shares (i.e. “realize” their capital) or pass them on. 10 . It is also necessary in the event of inheritance: the value of the shares will be used by the tax authorities to determine the tax base for inheritance tax.

The other two keys to the success of double-entry bookkeeping are more technical in nature:

- It is an intrinsic source of control over recorded data: each entry is simultaneously credited to and debited from two different accounts, thus preventing data entry errors.

- It is standardized, making it easier to monitor performance ratios from one year to the next, to make comparisons between companies, and to determine tax bases for the government that are reliable enough to stand up in court.

But these latter functions are only of fairly technical interest, whereas the central purpose of accounting is to provide decisive information to shareholders: tracking their capital contribution. It is designed first and foremost for this purpose, and the concepts it uses all derive from it.

Capitalism was thus able to develop by relying on an efficient and precise instrument, thanks to which the desire to enrich oneself was satisfied by economic activity (and not by theft or predation) and placed at the service of economic development. It would be an understatement to say that this combination of passion and tools has been a powerful one. However, as we shall see below, the limits of this tool make it a powerful predator of nature and mankind when it is not sufficiently supervised (see Essentiel 7 on the failure of accounting to take nature into account).

Find out more

A few references on the history of accounting:

- Yves Renouard, Les hommes d’affaires italiens du Moyen-Age, Armand Colin, 1949

- Jacques Richard, Révolution comptable, éditions de l’Atelier, 2021

- Maxime Izoulet’s thesis, Accounting theory of money and finance, EHESS (2020)

- Jacques Richard, Alexandre Rambaud, Didier Bensadon, Comptabilité financière, Dunod, 2018.

- Mémento Comptable 2022, Éditions Francis Lefebvre, in particular Title I “Basic accounting rules”.

The purpose of accounting is to determine the evolution of a company’s balance sheet and the results of its annual activities.

On the face of it, accounting is limited to recording expenses and revenues, enabling management (and third parties, including lenders) to ensure that the company is not “living beyond its means”.

The invention of “double-entry bookkeeping” goes much further than that. It reveals two main types of information:

- company assets, via the balance sheet 11

- the results of its activity over a given period via the income statement

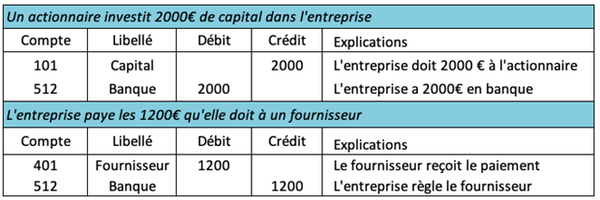

As you can see from the image below, the income statement and balance sheet are interconnected. In the balance sheet, the “Profit for the year” line is the balance (positive or negative) of the income statement.

Understanding the link between a company’s balance sheet and income statement

Source Download the file used to create the accounting tables (balance sheet, income statement, intermediate management balances).

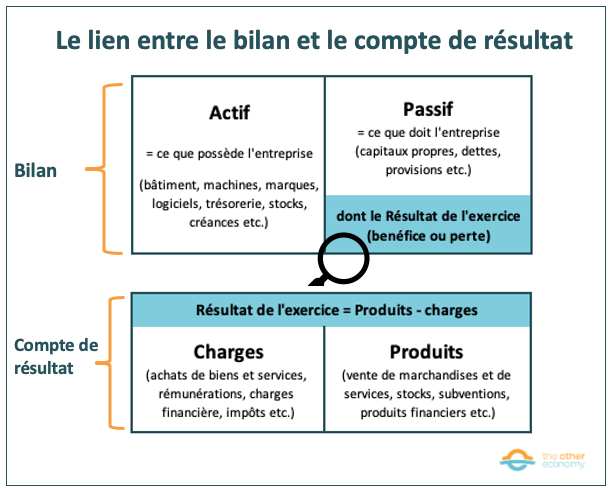

The balance sheet: what the company owns and owes

The balance sheet is a snapshot at a precise moment in time of what a company owns and what it owes.

A company’s balance sheet

Source Download the file used to create the accounting tables (balance sheet, income statement, intermediate management balances).

The liabilities side of the balance sheet shows the company’s “resources” or sources of financing: shareholders’ equity (also known as equity capital) and debts contracted by the company with bankers, suppliers, public authorities and employees.

The assets side of the balance sheet shows how the company has used its financial resources: these may include physical assets (buildings, vehicles, machinery), financial assets (receivables, shares in other companies), intangible assets (patents, copyrights, trademarks) and cash.

Definition: a company’s equity

Shareholders’ equity is part of a company’s financial resources. It comprises, on the one hand, share capital (i.e. the capital contributed by shareholders through the subscription of shares) and, on the other hand, the profits made each year by the company when shareholders decide to add them to shareholders’ equity (in the form of reserves or retained earnings). They are an important company resource for two main reasons:

1. In theory, there are no compulsory charges associated with equity (unlike interest charges on borrowings), although in practice the payment of dividends may be a source of income. 2 to shareholders is most common when the company is making a profit.

2. The level of equity determines the maximum loans the company can obtain.

Finally, it should be noted that shareholders’ equity is a liability of a rather different nature to other debts. Share capital is intangible, and can only be reduced by a decision of the Extraordinary General Meeting of Shareholders (in which case it is partly repaid). Moreover, in the event of liquidation of the company, shareholders are “served” last (in practice, they do not get back their stake). In short, shareholders’ equity is a “debt” that is riskier than any other.

Source For more on the legal status of capital in accounting, see Richard and Rambaud 2021: “Economics Accounting and the true nature of capitalism” and “Capital in the history of accounting and economic thought”, Routledge editions, and Le Cannu and Dondero, Droit des Sociétés, 2012 Ed Montchrestien.

The balance sheet is, by construction, always in equilibrium. Any entry that causes an asset item to move in one direction is “counterbalanced” by an entry of an equivalent amount, either in the opposite direction on the assets side, or in the same direction on the liabilities side. For example, if I borrow 100 from the bank, I have +100 on the liabilities side in debt and +100 on the assets side in cash.

It should be noted here that the titles to property (buildings, software, etc.), debts and receivables shown on the balance sheet all belong to (or are owed by) the company as a legal entity. The accounting system is asset-based, and records few assets or debts that do not belong to the company.

This is one of the reasons why it does not account for the impact of the company on natural assets that do not belong to it (see Essentiel 7 on the failure of accounting to take nature into account).

The income statement: what the company spends and earns

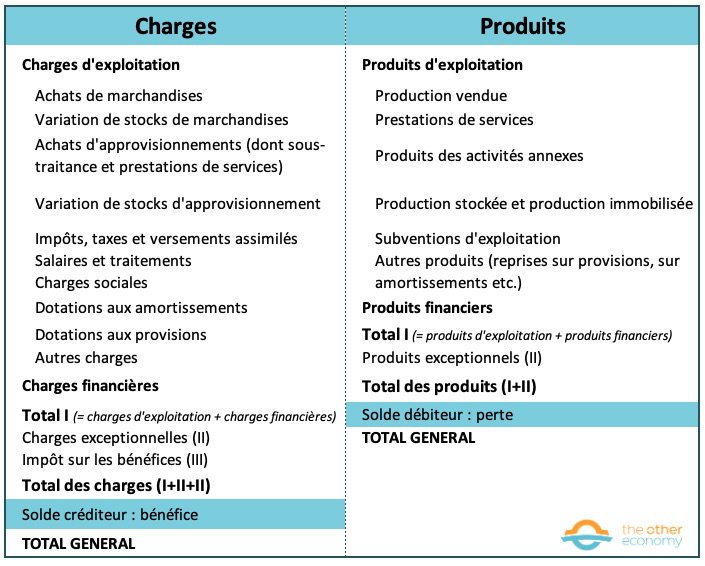

The income statement (or “profit and loss” statement) balances the flows of “income and expenses” for the year in question, and at the end of the year determines the profit or loss for the year, i.e. whether there has been a profit (i.e. income greater than expenses) or a loss (i.e. the opposite). Unlike the balance sheet, which shows the stock of what the company owns and owes, the income statement shows flows.

A company’s income statement

Source Download the file used to create the accounting tables (balance sheet, income statement, intermediate management balances).

At the end of the financial year, the results are approved at the Annual General Meeting. If the result is negative, it reduces shareholders’ equity in the balance sheet. 13 . If the result is positive, shareholders may decide either to retain it in the company’s accounts (in which case it increases shareholders’ equity), or to distribute it in the form of dividends. 2 in proportion to their “stake” in the capital. This is how shareholders know “where they stand”.

Accounting is essential to business life

As mentioned in Essentiel 1, accounting is essential for shareholders, as it enables them to monitor the use made of their capital contribution. More generally, accounting provides a better understanding of a company’s economic and financial situation, which is fundamental to its proper operation and, above all, to its interactions with other economic players.

Corporate accounting has many functions:

- It is used to record transactions carried out by the entity concerned (payment of salaries and invoices, invoices issued following the sale of goods and services, recognition of fixed assets, etc.).

15

cash movements, borrowings, changes in shareholders’ equity, etc.).

- It limits the risk of fraud or abuse (thanks in particular to the double-entry mechanism).

- It can be used to calculate indicators that are useful for directors, managers, tax and social security authorities (Urssaf in France), and other stakeholders (shareholders, customers, suppliers, bankers) when they have access to them; some of these indicators are also governed by regulations (particularly in the banking sector).

- For joint-stock companies (whether listed or not), it provides information that can be used to value the shares.

How are a company’s shares valued?

You might think that to calculate the value of a company’s shares, all you have to do is divide the total amount of shareholders’ equity by the number of shares. In reality, it’s more complex than that.

For a listed company, the value of a share is its exchange price on the stock market. Market participants decide to buy or sell a company’s shares based on an analysis of its financial situation (and therefore on accounting indicators), but also on extra-financial information (reputation, scandal, etc.) or on the dynamics of the market itself. But if they decide to buy or sell 16 it’s “at market price”. They have no choice. Of course, they take the risk that this price may later move in a direction contrary to their interests (i.e. downwards if they have bought, or upwards if they have sold).

For an unlisted company, there is no market price. Expert appraisals are therefore required to assess the value of the shares. This assessment can be based on a variety of methods: calculations based on sales, net income or projections can be corrected by other non-accounting data (e.g. market share, company reputation, estimated brand “value”, etc.).

The most important management indicators are :

1. Cash flow and ability to generate it. A cash-strapped company unable to pay its suppliers, employees or other stakeholders must file for bankruptcy with the Commercial Court. 17 .

Contrary to popular belief, a company can make a profit while seeing its cash flow dwindle.

Let’s imagine, for example, that a company uses €100k of cash to buy premises.

On the assets side of the balance sheet, we’ll see -100 in cash and +100 in property value. Its cash position has therefore shrunk.

On the other hand, in the income statement, the €100k investment will not be counted in full: the cost of purchasing the premises will be smoothed over the period of use. This is known as depreciation. If the estimated useful life is twenty years, we will charge €5k per year. Net income in the year of purchase is therefore much less affected than cash flow.

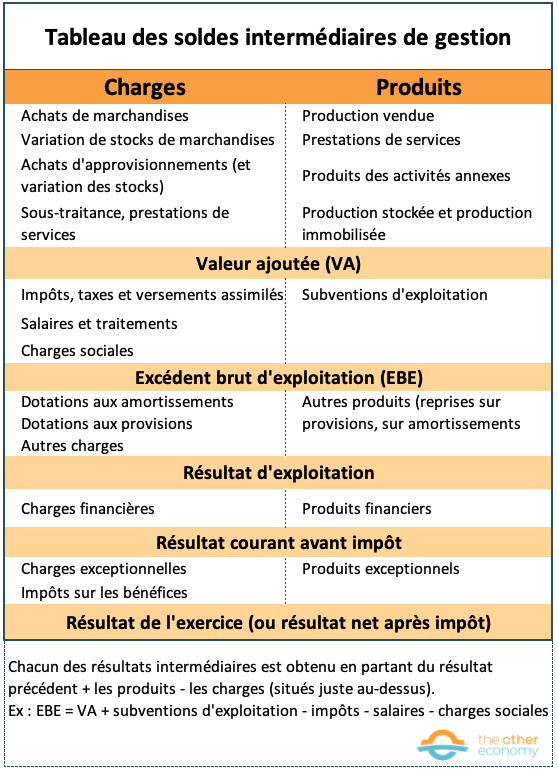

2. Results” (operating, current before tax and net after tax) are differences, or balances, between income and expenses. The three most important management balances are :

- operating income, which measures the extent to which the company’s production activity covers production costs;

- income before tax and exceptional items, which is deducted from operating income by adding net financial income (positive or negative);

- net income after tax, which is deducted from ordinary income by adding extraordinary income and deducting corporate income tax. Net income is also known as profit.

Understanding a company’s intermediate management balances

Source Download the file used to create the accounting tables (balance sheet, income statement, intermediate management balances).

Other financial indicators from the Anglo-Saxon world are commonly used in the financial communications of large companies:

- EBITDA (Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) = EBITDA less operating provisions;

- EBITDA minus depreciation and amortization ;

- NOPAT (Net Operating Profit After Tax) = earnings before interest and extraordinary items ;

- NBI (net income attributable to equity holders of the parent) = net income for the year less minority interests not attributable to the Group.

The experience of company management shows that it is impossible to do without the accounting tool. Experience also shows that it is far from sufficient. Accounting, which tracks past flows and inventories and can be used to make quantified projections, is not the way to develop a strategy or mobilize a team.

Accounting cannot be considered in isolation from a certain conception of business

While accounting is often seen as a neutral information system designed to measure a company’s wealth and income, in reality this is not the case.

For accountants, results, profits and costs, which many consider to be objective data, are conventional data, i.e. subject to predefined legal rules. 18 .

However, these conventions convey a vision of the company 19 . They are the fruit of social and political processes in which the players compete to shape, in their own way, the representation and distribution of the wealth produced by companies. This is what we will see, for example, in Essentiel 9 for IFRS international standards.

Accounting cannot be considered in isolation from a company’s vision of its purpose and governance. It is both a reflection and a structuring element of this vision. As we shall see in Essentials 5, accounting is also the source of concepts used in such everyday terms (cost, profit or earnings, expenses, etc.) that they seem perfectly neutral and “self-evident”, whereas in fact they are part of the conception and propagation of a specific vision of the company and its relationship with its various “stakeholders”.

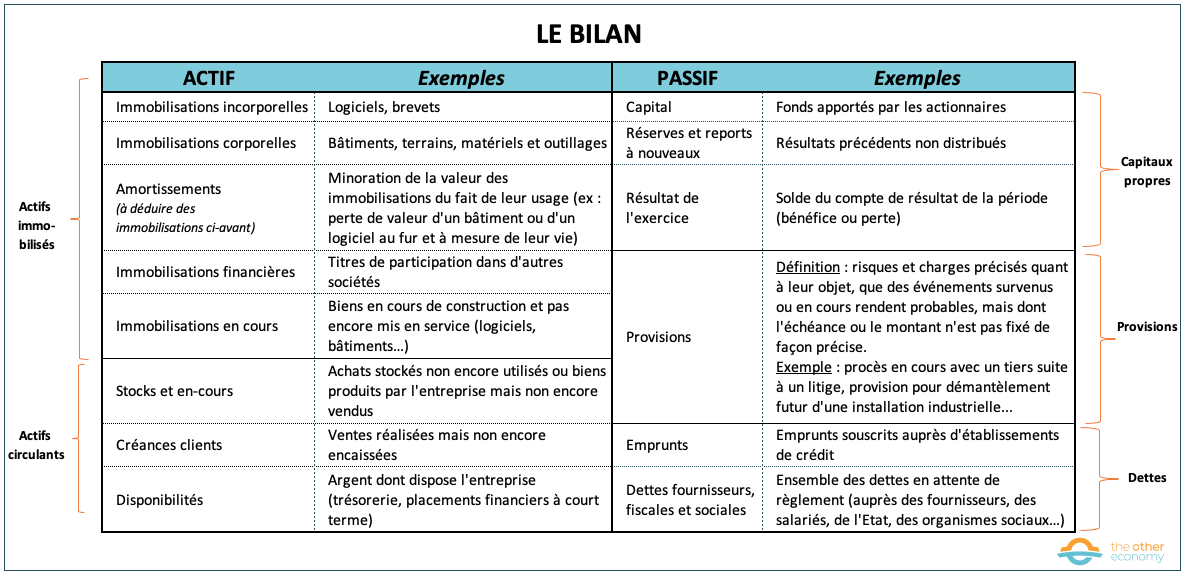

Accounting systems convey different visions of the company

In a collective work, Jacques Richard and his co-authors classify accounting systems according to the economic systems in which they were developed.

The former USSR and Yugoslavia had developed different accounting systems to those we know today, one with a statist orientation, the other self-managed.

Within the capitalist system, they distinguish :

- liberal systems: entrepreneurial, shareholder phase 1, shareholder phase 2 ;

- social-democratic, co-managerial, state-regulated systems.

As can be seen from the diagram below, depending on the accounting system and the point of view it supports, the concept used to determine profit or loss is not at all the same.

Should a company serve its shareholders?

What is a company and what are its objectives have been, and still are, the subject of fundamental debate. These debates are reflected in the various theories of corporate governance, i.e. all the processes, regulations and institutions designed to govern the way in which a company is managed and controlled. Accounting also contributes to structuring the way a company is perceived.

The predominance of shareholder value

For some economists, business leaders should only be concerned with the profit they can generate, and thus act in the public interest. In 1970, Milton Friedmann wrote a famous article for the New York Times, explicitly entitled The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.

In his book Capitalism and Freedom (1962), he also stated:

“Few developments could so profoundly undermine the very foundations of our free society as the acceptance by corporate executives of a social responsibility other than that of making as much money as possible for their shareholders. This is a fundamentally subversive doctrine. If businessmen have a responsibility other than that of maximum profit for shareholders, how can they know what it is? Can self-appointed private individuals decide what is in society’s interest?”

It thus clearly expresses the “shareholder value” principle, now prevalent in corporate governance: managers should not be concerned with social or environmental performance, but concentrate on financial performance to serve shareholders.

Agency theory

There’s nothing automatic about company directors acting in the best interests of their shareholders. How can we make this a reality?

This is the question that economists Jensen and Meckling set out to answer in their seminal article on agency theory. 20

This theory is based on the premise that the company is a set of contractual relationships between individuals. In their article, the authors focus on the relationship between the “principal” (the shareholder(s)) and the “agent” (the manager(s)) he hires to perform a service on his behalf, via a delegation of decision-making power.

Since there is an asymmetry of information between shareholders and the company’s management (who have more knowledge about how the company is run), mechanisms need to be found to align their interests. In this way, managers would be led to manage the company with a view to maximizing the return on capital to unlock shareholder value.

In terms of corporate governance, this takes the form of incentive mechanisms (e.g. stock options, variable compensation for managers based on company results, etc.) designed to align the interests of company executives and managers with those of shareholders.

As we will see in IFRS Essentials 9, in accounting terms this means that accounting is essentially designed to provide information of interest to investors, much more than to the company’s other stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, public institutions, etc.).

These two major theories, shareholder value and agency theory, are the ones that have most influenced corporate governance as it exists today. This can be seen by reading the G20 and OECD Principles of Corporate Governance (2017), which aim to help policymakers assess and improve the legal, regulatory and institutional framework organizing corporate governance. A glance at the summary shows just how central the role of shareholders is.

The company at the service of its stakeholders: stakeholder value

The company’s vision of serving its shareholders is highly questionable.

On the one hand, the idea that a company “belongs” to its shareholders, popularized by the economist Milton Friedman, is legally false and has been challenged since the 90s by French, English and American jurists. 21 .

The company is a legal entity under private law. It cannot be owned by another legal entity or by individuals. Shareholders own their… shares, which gives them powers (not ownership).

Olivier Favereau explains this very clearly in a short video.

On the other hand, the fact that a company’s primary objective is to make a profit is not self-evident, as illustrated, for example, by the recent debates in France over the definition of a company.

“A partnership is formed by two or more persons who agree by contract to allocate property or their industry to a common enterprise, with a view to sharing the profits or benefiting from the savings that may result”.(article 1832 of the French Civil Code)

This article makes profit the purpose of a private company. On the contrary, profit could be seen as a means to an end, the company’s mission or raison d’être. It should be noted in passing that the “profit” or benefit mentioned in the Civil Code is an accounting term: once again, we see the extent to which the concept of business and accounting are intrinsically linked.

There has been, and still is, a lot of talk about this subject.

For example, in the collective work 20 propositions pour réformer le capitalisme 22 the authors proposed rewording article 1832 of the Civil Code as follows:

“The corporation is formed by two or more persons who agree by contract to assign property or their industry to a common enterprise with a view to pursuing a business project that respects the general interest, financed by means of profit.”(Vingt propositions pour réformer le capitalisme – Proposition 2)

In France, this proposal has been taken up in the 2019 Pacte law, but in a watered-down form. Article 1832 has not been amended: the purpose of the company remains profit, even if the introduction of the notions of “raison d’être” (Article 1835 of the Civil Code) and “mission company” (Article L210-10 of the Commercial Code) have opened up new possibilities.

Furthermore,Article 1833 of the French Civil Code stipulates that “the company shall be managed in its corporate interest, taking into consideration the social and environmental stakes of its activity”, in addition to the obligation to have a “lawful object” and to be “constituted in the common interest of the associates”.

Finally, it is clear that the pursuit of profit is not necessarily a source of general interest. The corporate social responsibility (CSR) movement believes that the “alignment of the planets” between the interests of shareholders and the general interest is not a spontaneous occurrence. And there is no shortage of examples of companies that have made a lot of money for their shareholders by abusing their staff or natural resources.

Find out more

- See our detailed article on shareholder profit maximization theory in the module on Business in the Anthropocene Era.

- Christophe Clerc, Structure et diversité des modèles actuels de gouvernement d’entreprise – Part I and II, reports for the ILO (2020)

- Olivier Weinstein, “Theories of the firm”, Idées économiques et sociales, vol. 170, n°4, 2012, pp. 6-15.

- Olivier Favereau, “Pour un nouveau modèle d’entreprise”, in Rapport Moral sur l’Argent dans le Monde, Association Europe-Finances-Régulations, 2013

- Manuel Alfonso Garzón Castrillón, “The concept of corporate governance”, Revista Científica Visión De Futuro, vol. 25, n°2, 2021, pp.178-194

- Philippe Chapellier et alii (dir.), Comptabilités et société : entre représentation et construction du monde, EMS éditions, 2018

Accounting and its vocabulary are not neutral: they structure our representations of the economy.

Accounting helps company managers and sheds light on company life for stakeholders, but only from one point of view: that of the owners of the company’s capital. This is what we’ll be looking at below, showing just how misleading terms can sometimes be.

Profit, value, cost: ambiguous notions

Profit” is what makes it possible to “remunerate capital” (by distributing dividends, for example). 2 ), or to develop the company (by leaving it to reinvest), or to increase the value of shareholders’ equity (by leaving it as retained earnings). This is the source of “capital accumulation” in Marxist terminology. In the world of business schools and business, the expression “to make a profit “ is often replaced by “to create value”, by which we mean for shareholders. This confusion created by the use of the word value is obviously damaging, but illustrates our point: this accounting term refers to a moral category that is far superior to it. Value cannot be reduced to this purely financial notion, which is also limited to a category of economic players.

Indeed, a company can be seen as a human adventure, an innovative project, a challenge to be taken up, and so on. Even on a purely capitalist level, shareholding has been seen in the economic history of the last few centuries as proof of support or involvement, without necessarily a frantic quest for short-term returns. It was fashionable in wealthy families to preserve “values”: the notion was then more moral than it is today. Commitment to a company could be linked to the values (moral or otherwise) upheld by that company and its project, and not just to its ability to “make money”.

The term profit (like the term value) is also a source of confusion: the company benefits its stakeholders not just because it does or does not make a profit, in the accounting sense of the term. A supply purchase is made for the benefit of a supplier, and so on.

A salary benefits… the employee, whereas it is seen as an expense from the point of view of accounting and therefore shareholders.

In macroeconomic terms, the closest indicator to aggregating profits is GDP (gross domestic product). It is not made up of total corporate profits, but of the total income generated by economic activity, whether derived from labor (wages and salaries and self-employed earnings of sole proprietors, etc.) or from other sources (wages and salaries of self-employed workers, etc.). 24 ) or from capital (profits and rents), i.e. the value added generated by all companies (and government agencies). 25 .

The paradox is clear: from the point of view of corporate accounting (and its manager), salaries are expenses – and therefore need to be reduced – whereas from the point of view of the community, they are contributions to GDP. Profit is generated by reducing all the company’s expenses, which are sources of profit for its stakeholders (salaries are resources for employees, purchases are resources for suppliers, etc.).

The term “cost” is also ambiguous. The cost of a good is not an objective notion: it can only be clearly and precisely defined for a “given subject” (the person to whom the good costs), as can be seen from the titles of Claude Riveline’s management course.

Are employees a cost for the company?

As the authors of an article published in 2018 point out, the fact that in accounting logic, employees are always “considered from the point of view of what they cost and never what they bring in” is not neutral. This contributes to the belief that reducing the wage bill, and therefore expenses, necessarily contributes to increasing company performance. However, employees, their skills and their workforce are of course also resources for the company. The authors insist on the need to propose other ways of considering employees within the accounting system.

Paul Jorion insists on the difference in treatment between salaries and dividends: “A fair division requires a rethink of the accounting rules that treat salaries as costs and management bonuses and shareholder dividends as profit shares, to consider them all together as advances made on an equal footing to the production of goods or services.”

Source Read more in ” Les salariés ne sont pas une ‘charge’ comptable “, collective opinion piece, Le Monde, July 11, 2018.

The search for “value creation” for shareholders does not lead to the general interest

As we saw in Essentials 4, some economists claim that companies should only be concerned with “value creation” – in other words, the profit they are able to generate – and that this is how they act in the general interest. This is tantamount to asserting that accounting is a sufficient instrument for companies to do good, and that their actions, guided by this simple criterion, enable them to achieve the best economic situation from the point of view of the general interest.

This vision, which is dogma for “neoliberal” economists, is not in line with empirical reality or common sense. A company director riveted on his accounting and financial performance, and therefore on his profit (in the short or medium term, and therefore basically only on the fructification of his capital), has no reason to take into account everything that is not “revealed” in his accounting. If he considers that he can get what he wants at the lowest cost, he will not take into account natural resources (see Essential 7), social inequalities or employee satisfaction.

In particular, if the labor “market” allows, he may prefer to have access to high-performance, “disciplined” staff. If, over the long term, a machine produces at a lower cost than people, whose wages and charges (and all associated costs) must be paid, the manager must (from an accounting point of view) mechanize, i.e. replace people with machines. If it is more profitable to outsource production or a service to a country where wages are lower and the workforce less protected, or to a country where environmental standards are less stringent, he must also, from a strictly accounting point of view, do so.

Labor law and environmental regulations exist to set limits on this unbridled pursuit of profit. For example, the proposed carbon tax at the European Union’s borders is designed to ensure that European carbon emission standards do not disadvantage companies producing within the Union and drive them to relocate.

More generally, the predominance of shareholders’ interests is to the detriment of the company’s other stakeholders (employees, suppliers, customers, etc.), since it leads to the reduction of costs to the maximum, often neglecting the quality and above all the health or environmental impact of the products sold.

The quest for short-term financial profitability and a very high return on capital can, moreover, be to the detriment of the company’s long-term viability. Shareholder remuneration becomes a potential strategic priority, even when profits exist but are not at the level expected by shareholder standards. By dispensing with investment projects that may be profitable, but whose profitability falls short of the required standard, shareholder governance ultimately threatens the sustainability of the companies themselves, and therefore of the stakeholders directly linked to them.

When companies buy back shares instead of investing

Putting shareholders first 26 can lead a company to use its profits to buy back its own shares, which mechanically boosts its share price. When a company buys back its own shares, the shares bought back are generally destroyed. This reduces the capital and the number of shares. This mechanically improves the stock’s short-term value. This is a technique for distributing money to shareholders, at the expense of investment and the company’s other stakeholders.

The phenomenon is far from anecdotal.

In 2019, buybacks in the US amounted to around $750 billion, while IPOs totalled $62 billion. In 2021, these buyouts are still massive 27 .

Source See Rachats d’actions : quand le capitalisme tourne en rond and Les rachats d’actions record en Bourse relant le débat sur le partage de la valeur avec les salariés, Le Monde, 2021.

Accounting information is the basis for entrepreneurial autonomy and incentives to act

An entrepreneur (whether alone or as part of a team) enjoys a high degree of decision-making autonomy. However, this autonomy is limited in economic terms by the need to finance his activity, and in legal terms by the regulatory constraints imposed by the rule of law.

Accounting provides managers with the information they need to determine their business financing requirements. This can be achieved by self-financing (by leaving sufficient profits in the company for this purpose), by borrowing (from bankers or by issuing debt securities where this is possible), or by strengthening shareholders’ equity (with shareholders “going back into the pot”).

This economic autonomy is a strong incentive to “go it alone”. It allows a freedom of action and decision-making that a person in direct economic dependence on his boss, such as an employee, does not have. Remember that the salaried contract is a contract of subordination. When the employer is the State, this subordination is accompanied by a right of reserve (civil servants are not free to criticize their employer), which reinforces the moral limitation on economic autonomy.

More generally, maximum freedom for all is inconceivable without a principle of subsidiarity. 28 such that the decision is taken at the level closest to its operational consequences, as is the case for the decision of the company director.

Recourse to this motivation (often referred to as “entrepreneurial freedom”) is an essential part of the company’s strategy. 29 ) lies at the heart of the distinction between “capitalism” and other conceivable or conceived economic systems. Communism in the former USSR, in the period when private ownership of the means of production was abolished, made such autonomy impossible even for agricultural “farms”. It has been proven that completely depriving oneself of this motivation is economically inefficient. Actors without any personal motivation to act, and acting purely out of obedience or fear, are generally not creative or even sensible…

There are situations in which the goodwill of the parties and their thirst for cooperation enable common goods to be managed intelligently, with the common interest taking precedence over the general interest. But in the case of the former USSR, the suppression of individual interests was not in the service of a common interest, but rather that of an oligarchy. On the other hand, experiments in the management of the commons (as analyzed by Elinor Oestrom) are generally territorial and cannot be generalized to economic life as a whole.

This motivation (autonomy) must not be confused with a thirst for enrichment, nor with the fact that accounting is inevitably doomed to reflect only the enrichment of the capitalist (to the detriment of the other “stakeholders”). It was to overcome this impasse, while preserving the contribution of accounting, that Jacques Richard came up with the following idea 30 then developed by Alexandre Rambaud 31 triple bottom line accounting, which integrates social and environmental issues.

In short, “making a profit” is a guarantee of independence and a way of applying the principle of subsidiarity in the economic world. This motivation should not be confused with the pursuit of profit for profit’s sake, the exclusive quest for money.

Accounting takes no account of natural resources and pollution

Accounting records flows or changes in inventories that concern individuals or companies (see Essentials 2 on the balance sheet and income statement). Nature does not charge for the services it provides, nor for the damage we do to it. As a result, withdrawals from the natural heritage or pressure on ecosystem services (see the module on natural resources), on which all economic activity depends, are not recorded in a company’s accounts. What’s more, they are generally not “appropriate”, as we shall see.

When nature belongs to no one

In the – very general – case where the element of nature is not privatized, a company’s accounting simply does not record its “consumption”.

For example, the destruction of pollinators and wild fish, and the modification of the atmosphere’s composition (whose greenhouse gas content is increasing, causing climate change) are not recorded in any company’s accounts.

This might seem legitimate for the vast majority of companies, whose pressure on nature is apparently marginal (not least because most of them are very small).

But these individually marginal actions exert an overall pressure that is becoming considerable.

In addition, some multinationals have a far from marginal impact:

- Fossil fuel industries extract, process or market massive quantities of oil, gas and coal, the combustion of which sends hundreds of millions of tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere.

- the mining sector is the largest generator of solid, liquid and gaseous waste of all industrial sectors 32 It is also the source of numerous social conflicts (the industry is responsible for the highest number of expropriations) and environmental conflicts (see the EJ Atlas database, which lists conflicts for environmental justice).

Growing awareness of the increasing ecological impact of economic activities has led many countries to develop pollution pricing tools (see box), as well as requiring companies to report on their environmental and social impacts (see Myth 5). However, these measures are still largely insufficient to ensure that nature conservation is truly taken into account in corporate strategy: destroying nature remains in most cases a source of profit, as demonstrated by the continuing good health of the fossil fuel industries.

Putting a price on pollution?

The term “negative externalities” refers to the negative repercussions of an economic agent’s activity on other agents, without any “spontaneous” monetary compensation. Local pollution (of a river, of the air, of a territory) or global pollution (of the ocean, of the atmosphere via GHG emissions) are therefore negative externalities.

To remedy this, economists propose to put a price on them, so that economic agents integrate the cost of pollution into their consumption and investment decisions. Carbon pricing (via a tax or a CO2 quota market) is thus the economists’ main measure for combating climate change.

Putting a price on pollution is indeed part of the solution, even if it’s not as obvious as it might seem (how to put a price on something that doesn’t have one, how to integrate the intergenerational dimension, etc.). Moreover, it’s not, as some economists would have us believe, the only solution. For example, while taxes and quotas do of course have an effect on a company’s bottom line, we mustn’t overlook ways of integrating pollution and the exploitation of nature much more directly into a company’s balance sheet.

Source Find out more about negative externalities and price signals in the Economics, Natural Resources and Pollution module.

When elements of nature are the property of the company

The situation is different when these elements of nature are appropriated by the company. If a mine or oilfield is privatized, its value is recorded as an asset of the mining or oil company.

The valuation of this mine (or field) over time must, of course, take into account its depletion, i.e. the fact that the resources it contains are depleted as and when it is exploited.

In certain industries, companies are also required to set aside provisions for decommissioning, i.e. to set aside reserves to restore an industrial facility, quarry or mine over time (for more details, see our fact sheet on decommissioning provisions ).

But even in this case, nature doesn’t necessarily get its due…

In fact, the financial valuation of the residual part of the mine or oilfield 33 may be higher than the initial valuation, which may encourage the entrepreneur to destroy nature in order to enrich himself. Accounting will not necessarily reveal the destruction of the asset, whose value could become very high… just before it collapses.

It may also be financially more profitable (depending on the discount rate used) for the entrepreneur to exploit the mine fully and quickly than to manage it “as a good father”, i.e. leaving resources for his children to exploit. This paradox is similar to what happened with whaling at the end of the 19th century.

Whaling and interest rates

In an article published in 1973, Canadian mathematician Colin Clark made a simple economic calculation comparing two strategies, one of “prudent management” of the whale stock and the other of killing all the whales and banking the proceeds. The result was striking. 34

Ivar Ekeland and Jean-Charles Rochet developed this example in their book Financial speculation must be taxed (p.103): “In short, the industry had a financial interest in liquidating the whales as quickly as possible, because money reproduced faster in the bank than cetaceans in the sea. Today, with interest rates close to zero, the same calculation would yield a different result, and the industry would perhaps be trusted. The calculation was decisive, and a moratorium on whaling was decreed. But isn’t it paradoxical that an irreversible decision, such as to extinguish an animal species, should depend on an eminently labile variable as unnatural as an interest rate?”

These simple observations are all it takes to understand that the path of total privatization of nature, proposed by many economists as the solution to the challenges of natural resource destruction and pollution, is a dead end.

This raises the question of whether it would not be legitimate for accounting to make it compulsory to record such destruction or pollution, which can be likened to a loss of assets. This is the approach taken by Jacques Richard and Alexandre Rambaud with a view to integrating ecological and social issues into accounting. Various research teams are currently examining this issue.

Climate-related financial risks: a concept that has yet to be translated into accounting terms

Financial players take climate risk into account

In September 2015, in his ” Tragedy of the Horizons ” speech, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chairman of the Financial Stability Board, states that global warming presents risks with potentially systemic financial consequences. He draws up the following typology:

Marc Carney’s typology of climate risks

- Physical risks: the impact of climate-related disasters on companies, production chains and trade;

- Transition risks: the impact of economic change linked to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions on carbon-based companies;

- Liability risks: legal action initiated by victims or other stakeholders.

Find out more about the systemic risks of global warming in the Finance module.

Marc Carney’s speech marked the beginning of the world of finance taking climate issues into account as a whole (and no longer just within departments dedicated to social and environmental issues). Since then, central banks have been conducting research to assess the extent to which the financial system is exposed to climate risks (see the module on money). An increasing number of financial players are considering how to reduce their exposure to the economic sectors most affected by these risks (see the module on finance).

An awareness that is not yet reflected in company balance sheets

Today, we know that complying with the Paris Climate Agreement will require the early closure of a number of high-carbon assets, such as coal-fired power plants and, more generally, fossil-fired industrial facilities.

We call stranded assets stranded assets “are those assets (factories, infrastructure, buildings, production plants) that will have to close before the end of their economic life, either for regulatory reasons (e.g.: political decision to phase out coal) or due to foreseeable destruction (e.g.: infrastructure and buildings built in areas flooded by rising sea levels).

In accounting terms, the materialization of stranded assets would have a number of negative impacts for the companies holding them.

On the one hand, they would obviously no longer be able to rely on the resources generated by the discontinued business.

On the other hand, they would see their expenses increase significantly and quite suddenly:

- the shortened lifespan of installations would lead to accelerated depreciation charges on the assets concerned;

- the majority of these facilities require provisions for dismantling, the costs of which are likely to be triggered much sooner than expected. 35

It’s easy to see that this scissor effect could quickly lead to bankruptcies.

At this stage, although work is underway to assess the value of these ” stranded assets “, no real thought seems to have been given to their translation into accounting terms, either by political bodies or by standard-setters. Given the importance of fossil fuels in the economic system, this failure to anticipate future asset closures is a major concern for financial stability (and, of course, for sustainability issues).

Accounting is based on fundamental principles and codified rules

Accounting standards include the fundamental principles, rules and methods to be followed when keeping an organization’s accounts. 36 Although there is a long-term trend towards convergence between different accounting systems, there are still differences between countries.

French companies comply with the general chart of accounts issued by the Autorité des normes comptables, German companies with the Deutschen Rechnungslegungs Standards (DRS) issued by the Deutsche Rechnungslegungs Standards Committee, and US companies with USGAAP.

There are also international accounting standards (IAS – IFRS). 37 Very similar to American standards (USGAAP), they were developed in the 1970s to enable capital market investors to compare the financial performance of companies(see point C). These standards are widely applied throughout the world. For example, all listed companies in the European Union must publish their consolidated financial statements in accordance with these international standards.

Principles designed to ensure the accuracy and continuity of financial statements over time

Accounting is based on a number of conventions known as “accounting principles”. Developed over time, these very general principles serve as a frame of reference for accounting standard-setters, i.e. the institutions that enact and develop accounting standards (such as the Autorité des normes comptables in France). They also provide corporate accountants with a principle to guide their accounting decisions when they are faced with a specific question and there are no standards detailing this particular case.

The aim is to ensure that accountants use concepts and methods that have been defined in advance and accepted by all, so as to limit as far as possible their room for manoeuvre in modifying the content of the accounts, and to ensure that they reflect the most faithful possible image of the assets, financial situation and results of the entity in question.

In some countries, such as the United States, the principles and concepts required to understand and apply accounting standards are defined in a single document known as the “conceptual framework”.

This is also the case for the IFRS international standards, whose conceptual framework sets out the addressees of financial information, the objectives of financial statements, their components, the underlying assumptions and the qualitative characteristics of financial information.

In other countries, such as France and Germany, the main accounting principles are enshrined in law. In France, for example, the main accounting principles listed below can be found in the Commercial Code. Although these principles are found in most accounting systems, they may be subject to different interpretations (see the concept of prudence below).

The main accounting principles of French GAAP

- Going-concern principle: we assume that the company will continue to operate (if it does not, this would have an impact on the value of its assets, which would then be valued at their net asset value, i.e. at their expected selling price rather than their purchase price).

- Principle of specialization of accounting periods: supply of periodic information by separating accounting periods and allocating expenses and income to each period.

- Principle of nominalism: respect for the nominal value of money without taking into account variations in its purchasing power (historical cost).

- Prudence principle: avoid transferring present uncertainties that could affect the company’s assets and earnings to future periods. Under French GAAP, this principle refers to asymmetrical prudence (unrealized losses for the year are recorded, but unrealized gains are not). 38 The IASB (International Accounting Standard Board), which issues international standards, takes a more nuanced view of this principle. Prudence was introduced into the IASB’s conceptual framework only in 2018, from the angle of seeking neutrality, ensuring that assets and income are not overstated, and liabilities and expenses are not understated. This position can sometimes lead to certain assets being revalued at their current value, thereby revealing unrealized capital gains.

- Principle of consistency: the accounting methods used and the structure of the balance sheet and income statement may not be changed from one year to the next, except in exceptional cases, in order to give a true and fair view of the company’s assets and liabilities, financial position and results of operations.

- Materiality principle: it is assumed that management is aware of the reality and significance of the events recorded. This is in line with the notion of sincerity expected of management.

- Non-compensation principle: assets and liabilities must be valued separately. No offsetting is allowed between assets and liabilities on the balance sheet, or between income and expenses on the income statement.

- The principle of good information: beyond compliance with rules and principles, the key issue is to provide the various users of financial documents with satisfactory information, i.e. information that is sufficient and meaningful to understand them.

- Principle of intangibility of the opening balance sheet: the opening balance sheet of a financial year must correspond to the closing balance sheet of the previous year. The application of this principle prohibits the correction of the previous year’s closed accounts.

What impact would the application of these principles have on ecological and social issues?

This would make it possible, for example, to benefit in the area of non-financial indicators from the rules of sincerity and fair presentation developed over time for the financial sector. It would thus no longer be possible to modify non-financial reporting from one year to the next if an environmental or social indicator showed an unfavorable result.

More fundamentally, the application of the principle of prudence or non-compensation to environmental issues could serve as the basis for an in-depth modification of accounting to integrate nature.

The difference between parent company and consolidated financial statements

All companies are required to publish their parent company financial statements. Companies made up of several companies (e.g. multinationals) must also publish consolidated accounts.

- Parent company (or individual) financial statements

These are the accounts of each individual company. They are most often based on standards issued at national level (although national regulators may draw inspiration from, or even adopt international standards in their entirety), and are used to determine the company’s taxable income, i.e. the income that will serve as the basis for calculating the tax payable by the company. In France, the regulatory body for the private sector is the Autorité des normes comptables (ANC). Parent company financial statements are prepared by all companies, including those belonging to a larger group.

- Consolidated financial statements

They present the accounting and financial position of a group as if it were a single company. They are drawn up by the parent company on the basis of the individual financial statements of each of the companies making up the Group. Consolidation techniques are, of course, also standardized. The financial communications of major groups, and the results announced in the media, are always based on consolidated accounts.

International standards to support the development of capital markets

As we have seen, company accounts are drawn up on the basis of standards defined at national level. However, the development of capital markets from the 1970s onwards created a need for uniform accounting standards for large listed groups, to enable investors to compare their accounting and financial statements.

IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards)

Launched in 1973, work to develop international accounting standards is now carried out by the International Accounting Standard Board (IASB), hosted by the IFRS Foundation, a not-for-profit organization registered in the US state of Delaware.

This work led to the development of international standards, known as IAS, International Accounting Standards (for those developed up to 2001, of which some twenty are still in force), then IFRS (for those developed after 2001, covering 17 topics). The members of the IASB are also responsible for promoting the use and worldwide adoption of these standards.

On its website, the IFRS Foundation states that its aim is to serve thepublic interest. However, the significant presence of auditing firms (Deloitte, PWC, KPMG, EY) in the governance of this foundation is a source of concern. 39 raises the question of the independence and, above all, the absence of conflicts of interest of this institution.

Indeed, the standards it develops are extremely complex, which necessarily leads to the creation of assignments for these large audit firms to help companies understand and implement the standards, and then audit their accounts.

Which companies are affected by IFRS?

These standards apply primarily to the consolidated financial statements of listed and financial companies, but may also apply to those of unlisted companies, as well as to parent company financial statements. In 2009, IFRS were simplified and adapted for SMEs (and revised in 2015).

IFRS are not mandatory: each country decides whether or not to use them. However, they are widely used throughout the world. According to the IFRS Foundation, 144 jurisdictions (out of 166 analyzed) require the adoption of IFRS for all or most of their listed companies and financial institutions.

However, this is not the case in some of the world’s leading economies. For example, Japan allows IFRS on a voluntary basis for national companies; China has adopted national standards substantially in line with IFRS, but has no plans to adopt them completely; the USA requires its listed companies to issue their consolidated accounts in accordance with their national standard (US GAAP). 40 This is despite the fact that the USA is a member of the IASB, and has played a major role in the work leading up to the adoption of IFRS.

As we’ll see in Essentiel 9, the widespread adoption of IFRS throughout the world is far from neutral in terms of the way a company is represented, and has far-reaching consequences for management.

Within the European Union, limited room for maneuver

Since 2005, European listed companies have been required to present their consolidated financial statements in accordance with IFRS. 41 This decision amounts to an abandonment of sovereignty by the European Union and its member states on a major issue: the EU is committed to adopting the standards in extenso. It may choose, after consultation with various bodies 42 to adopt or reject them, but under no circumstances to amend them. In the event of rejection, it is up to the IASB to seek a compromise to satisfy all stakeholders. As a result, the EU’s room for manoeuvre to ensure that IFRS do not constitute an obstacle to the achievement of broader strategic objectives is extremely limited. In Essentiel 9, we analyze why IFRS pose so many problems.

IFRS accounting standards focus managers on short-term value creation

As we saw in Essentiel 4, today’s dominant view of the company is that it is an “asset”, or more precisely, a collection of assets and liabilities, held by one or more “owners” (shareholders) who seek to extract maximum value from it. This is undoubtedly one of the most striking developments in the economic system in recent decades (a development which has even given it a name: shareholder or financial capitalism).

Companies’ accounting and financial statements must be used primarily by investors

In accounting terms, the predominance of shareholder interests means that financial statements are prepared from an investor’s point of view. This is precisely the purpose of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) which, as we saw in Essentiel 8, have been adopted worldwide for the consolidated financial statements of listed companies. They are designed to account for the valuation of this set of assets and liabilities, each with a certain “autonomy”, from the shareholders’ point of view. The company is no longer seen as a collective at work, aiming to achieve a mission. Each asset or liability is subject to ad hoc transactions (sale, securitization, etc.).

IFRS standards at the service of investors

The IASB, the body that develops IFRS, specifies in the Conceptual Framework 2018 43 of IFRSs that, “The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the entity concerned that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity.“”

The website also states that IFRS:

– “brings transparency by improving the international comparability and quality of financial information, enabling investors and other market participants to make informed economic decisions.”

– “strengthen accountability by reducing the information gap between providers of capital and the people to whom they have entrusted their money.”

– “contribute to economic efficiency by helping investors identify opportunities and risks around the world, thereby improving capital allocation.”

Historical cost accounting and fair value accounting

To simplify matters, we often contrast the continental model, which favors “historical cost”, with the Anglo-Saxon model, which favors ” fair value”, a rather ambiguous term. 44

Historical cost accounting involves valuing assets in the company’s balance sheet at acquisition cost. This method of valuing assets is still used for company accounts in France and Germany. Thus, a building recorded at historical cost is at its purchase value, which is fixed; at fair value, it is at its resale value (which may vary according to the real estate market) and may therefore incorporate an “unrealized capital gain”. 45 contrary to the principle of prudence, defined in Essentiel 8, which prevails in historical cost accounting.

Under Anglo-Saxon standards, which have largely been adopted by IFRS, “fair value” accounting prevails. Most assets and liabilities should be valued at their current market value, the underlying idea being that when an asset is sold, its book value should be precisely equal to its sale value.

More specifically, IFRS 13 (“Fair value measurement”) defines fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an arm’s length transaction between market participants at the measurement date”.

When transactions are not directly observable, there are three valuation techniques:

- The market approach: The company relies on prices and other relevant information generated by market transactions on comparable assets, liabilities or a group of assets and liabilities;

- the income approach: the company calculates the present value of future cash flows generated by the asset;

- the cost approach: this last approach is essential, for example, to avoid writing off the value of financial assets that would have a zero market value (in the event of a major financial crisis), but a value in use.

The negative impacts of “fair value

Risks to financial stability

Numerous academic studies denounce the effects of fair value accounting on financial stability.

In fact, it exacerbates fluctuations in the financial system, and can trigger a downward-ascending spiral in the financial markets, even amplifying systemic risk. The balance sheet of a listed company whose shares rise for speculative reasons is artificially enhanced; conversely, its balance sheet is excessively devalued if its shares are subject to downward speculation.

This phenomenon of exacerbated fluctuations can mask a company’s real difficulties: the continuous rise in a share price creates an artificial wealth effect by masking an excessive debt ratio. This is what happened, for example, to Carillion, the UK’s second-largest construction and services company, which went bankrupt in June 2018 despite being in very good financial health a year earlier. When an entire sector is the subject of a speculative bubble (as with the internet bubble of the 2000s), or when this bubble affects the entire economy, the risk becomes systemic.

Focus on short-term shareholder value creation

The vision of the company as a collection of independent assets and liabilities leads us to envisage any dismantling or partial disposal operation without any consideration for the company’s “social body”. This leads to managerial behavior focused on maximizing the short-term “value” of each asset and liability.

If, in addition, executive remuneration is indexed to this value, it is easy to see that it greatly exacerbates the short-termism of their actions and the failure to recognize long-term impacts or any other impact not “materialized” in the accounts.

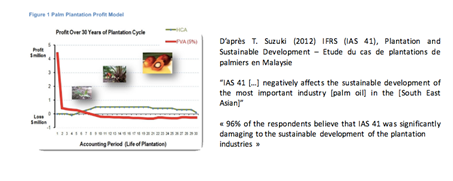

To illustrate this bias, consider the example developed by Professor Tomo Suzuki of Oxford University. 46 Applying IAS 41 (one of the IFRS standards that apply to biological assets) to an oil palm plantation over a 30-year period shows dizzying profits for one year, followed by low and then declining profits, and ending with a long period of low and stable losses. In contrast, the application of traditional historical cost accounting initially shows zero or negative results, followed by increasing profits, then stable profits, then slightly decreasing profits.

Without going into detailed analysis, it is clear that the IFRS standard, by showing a potential value for the plantation that would be that of its resale, may encourage very short-term speculative behavior by encouraging this short-term valuation, in order to sell and “realize” the capital gain.

In both accounts, however, nature is not counted, and the environmental disasters associated with palm oil production do not appear in either profit and loss statement…

Source Example cited by Alexandre Rambaud in a presentation at the Chaire Energie et Prospérité seminar.

IFRS standards penalize long-term investments, which are essential for the ecological transition

As we have seen, IAS/IFRS are primarily designed to inform investors. Broadly speaking, they provide them with the analytical tools they need to exert pressure on companies by selling their shares if the return on investment is below the average expected by the market and/or if dividends are not up to scratch.

By pursuing short-term financial profitability and distributing too large a share of profits, companies are reducing the number of investment projects they undertake, making them more vulnerable in the long term and limiting their ability to revise their business model in the direction of sustainability.

In an article published in 2024, Vera Palea, Alessandro Migliavacca and Andrew G. Haldane highlighted the reality of this phenomenon. Through an econometric analysis of over 5,000 European companies listed on the stock exchange over the last 30 years, they show that the transition to IFRS accounting rules has curbed investment by companies in all sectors by between a third and a quarter, given the opportunities available.

In the case of financial companies, this market pressure can lead them to reduce the length of time they hold their financial assets (high portfolio turnover rates), or to select high-risk projects that are profitable in the short term, to the detriment of long-term investment projects that are less profitable in the short term. In the 2014 Global Financial Stability Report, the IMF expressed concern, for example, that banks had increased their financial risk-taking (acquisition of financial assets) to the detriment of their economic risk-taking (financing of productive investment).

Find out more

- International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), Samira Demaria and Sandra Rigot, La Découverte, 2018

- Financial accounting, Jacques Richard, Didier Bensadon and Alexandre Rambaud, Dunod, 2018

- Jacques Richard, The dangerous dynamics of modern capitalism (from static to IFRS’ futuristic accounting), Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 2015

- Samira Demaria, Sandra Rigot, The Impact on Long-Term Capital Investment of Accounting and Prudential Standards for European Financial Intermediaries, Revue d’économie politique, 2018

- Vera Palea et al, Is accounting a matter for bookkeepers only? The effects of IFRS adoption on the financialisation of economy, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2024

Preconceived notions

Accounting gives an objective and rigorous idea of a company’s performance

Accounting is generally seen and taught as a rigorous technique for recording income and expenditure, akin in the final analysis to what a good managerial household should do.

This vision is naïve. The organization of accounts is subordinate to a purpose (to represent what shareholders consider to be the value of their shares and its evolution), obeys a specific logic and uses a vocabulary that induces de facto value judgments. Clearly, calling profit what benefits only shareholders, or cost what costs them, induces a specific perception of what is a profit or a cost (see Essential 5). We have shown, in particular, that this logic leads to a failure to take sufficient account of nature and mankind.

What’s more, in many cases, and despite the auditors’ control work, there are still grey areas in the accounting results. Even from a strictly financial point of view, accounting cannot always provide an accurate assessment of a company’s value. The risks to which it is exposed (and which are supposed to be covered by provisions) are not always easy to estimate, because they may be poorly known or difficult to monetize.

That said, accounting remains a necessary tool that can be used intelligently if its limitations are understood.

Accounting would enable managers to increase the creation of value for shareholders, and therefore for society as a whole.

The prevailing view is that a company’s manager should focus on creating shareholder value. In fact, this is one of the most widely emphasized objectives of accounting. 47 and has been the subject of specific developments by practitioners 48 to further improve its use in this direction.

On the other hand, as we saw in Essentiel 5, creating value for the shareholder (i.e. simply enriching him) and for the company are two obviously distinct notions, but above all they have no causal link.

On the one hand, “value” for society is a complex ethical notion that varies over time, and whose definition obviously cannot be reduced to a quantitative notion, let alone an accounting one. Thousands of pages have been written, and will continue to be written, on what constitutes the common good, and this will always require democratic deliberation.

On the other hand, shareholder enrichment can contribute to this common good (or social value) if the activity that generates it and the way it is conducted contribute to it. There is no reason for this to be automatic. To take just a few examples, highly polluting companies can be highly profitable, as can companies that use child labor.

That’s why we’re seeing an increasing number of reflections on the raison d’être of the company, on mission-driven or impact-driven companies, on the company as an object of collective interest, and on the company as a contributor. Proposals have been made to amend article 1832 of the French Civil Code 49 which makes profit the goal of company creation. The PACTE law in 2019 amended article 1833 of the Civil Code, paragraph 2, which provides in its new wording that the company is managed in its social interest “taking into consideration the social and environmental stakes of its activity”. It has given legal form to the mission-driven company and its raison d’être (status and concept of voluntary application). (Find out more in Essentiel 4 on the importance of corporate design).

Find out more

- Blanche Segrestin, Kevin Levillain, La mission de l’entreprise responsable, Presses Des Mines, 2018

- The impact company movement

- Nicole Notat, Jean-Dominique Senard, L’entreprise, objet d’intérêt collectif, report to the Ministers of Ecological Transition and Solidarity, Justice, Economy and Finance, Labor, 2018

- Fabrice Bonnifet and Céline Puff Ardichvili, L’entreprise contributive – Concilier monde des affaires et limites planétaires, Dunod, 2021.

- Daniel Hurstel, La nouvelle économie sociale – Pour réformer le capitalisme, Odile Jacob, 2009.

- Félix Bogliolo, La création de valeur, éditions d’Organisation, 2000

Accounting is not economics

The vast majority of economists are not interested in accounting, which seems to them to be a matter of managerial practice and not directly related to their discipline. So, without realizing it, they use accounting terms to structure their thinking. But sometimes they use them in a totally different sense from accounting.

This doesn’t make things any easier for citizens.

Let’s take three examples:

1. For an economist, the term capital refers to physical assets (buildings or equipment), intangible assets (patents, brands, software, customer files) and financial securities (shares, bonds, etc.). For an accountant, all these items are assets on the company’s balance sheet. Capital, on the other hand, is entered on the liabilities side of the balance sheet (see Essential 2 to understand what a company’s balance sheet is).

Of course, this difference is by no means anecdotal: when we discuss the respective incomes of capital and labor, a major issue in the debate on social inequalities and the future of capitalism, what are we talking about?

2. For an economist, cost is not an accounting cost: it’s not an expense or a charge. It’s what it costs an “economic agent”, which, if he’s neoclassical, he’ll call a “disutility”. This cost may not be monetary, which is what accounting doesn’t see. It may, for example, be an “opportunity cost” (i.e. a loss of income linked to a choice that excludes an opportunity), which the accountant does not record.

3. As Michael Kalecki points out, “I have found out what economics is; it is the science of confusing stocks with flows“. 50 This may seem very odd, but the requirement to distinguish between stocks and flows (the basis of accounting and…physics) is not always respected in economic models. The discipline of ” stock-flow consistent ” models is therefore not widespread.

These discrepancies between accounting and economics might not pose major problems if everyday economic vocabulary and reasoning didn’t mix up the concepts and make them so politically important. It is clear, to take just one example, that the confusion maintained (deliberately or not) between the good management behavior of a State and that of a household is partly based on these misunderstood and poorly explained discrepancies (more explanations in the module on public debt). For some, this confusion legitimizes principles of “good management” that are unfounded in economic terms.

It would be impossible to change the accounting standards applied by millions of companies worldwide.

Accounting is a legal requirement for any company handling money. 51 Accounting standards are very similar from one country to another. There are four reasons why it would be very difficult to change them substantially.

1. Used by hundreds of millions of companies worldwide 52 and hundreds of millions of accountants, who are trained and accustomed to a centuries-old way of thinking.